“🌕 Something on the Moon Keeps Killing Our Spacecraft… And No One Knows Why 🤖💥”

There’s something deeply unsettling happening on the Moon.

For decades, humanity has dreamed of returning to its dusty surface. Billions have been spent. Countless missions launched. And yet, one after another, they fall. Not in orbit. Not on takeoff. But at the most

critical moment: the landing.

Japan’s Hakuto-R, America’s Intuitive Machines, Russia’s Luna 25, and others—every one, heralded as the return of lunar glory—ended the same way: crashed, shattered, silent.

And here’s the weird part.

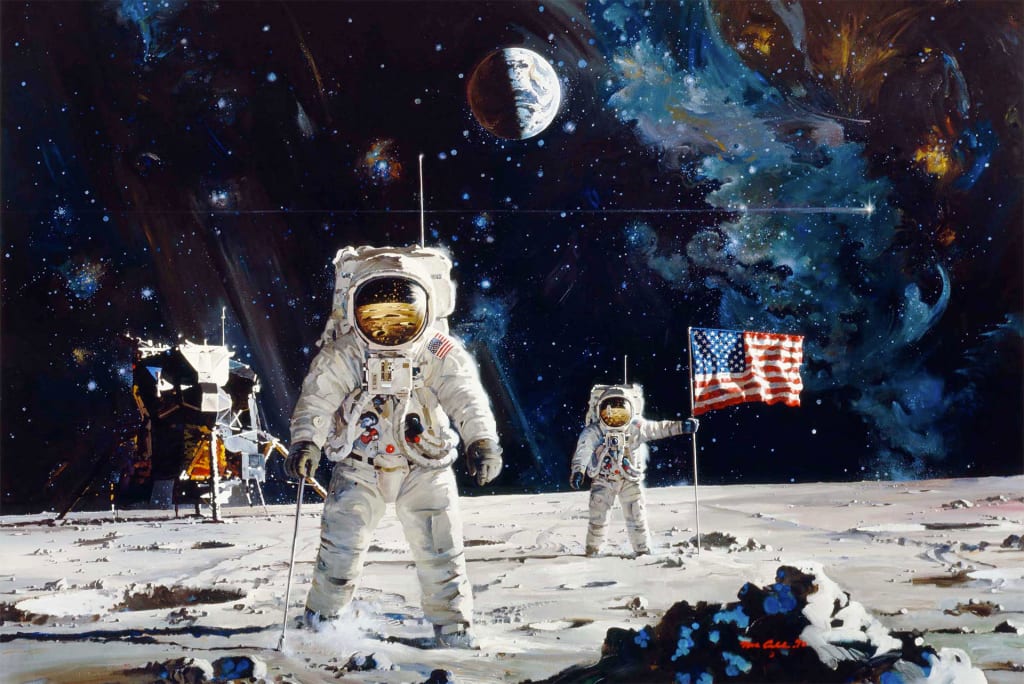

Back in the 60s and 70s, with hardware that looks like toys compared to today’s tech, we succeeded. The Apollo astronauts landed six times. Not because of advanced algorithms, but because of a quality our

machines still lack: instinct.

Neil Armstrong didn’t rely on sensors. He overrode them. As the lunar module drifted toward a boulder field, the computer said “all clear.” Armstrong said “absolutely not,” took control, and landed manually—

with 16 seconds of fuel left.

Today’s landers? They would have trusted the numbers… and crashed.

Which is exactly what’s happening now.

Japan’s Hakuto-R believed it was meters from the surface. In reality, it was five kilometers up. Its system shut down the engine. And that beautiful billion-dollar machine freefell to its death.

Intuitive Machines’ Nova-C did something eerily similar. Faulty data from its altimeter created a warped sense of altitude. By the time the software noticed, the lander was already tumbling toward the Moon, end

over end.

Then came Resilience. Packed with bleeding-edge sensors, it promised pinpoint accuracy. But the sensors didn’t activate until it was already falling at deadly speeds. Another crater added to the Moon’s graveyard.

The pattern is undeniable. Different countries. Different tech. Same flaw.

And it raises the terrifying question: Is the Moon rejecting our machines?

Let’s be clear. The Moon isn’t haunted. But it is hostile to perception.

Its surface reflectivity, known as albedo, changes constantly. Some areas shine like glass. Others absorb light like soot. For radar, lidar, and optical scanners trained on Earth-like conditions, this variability is a

nightmare.

One moment, the sensor sees the surface. The next, it doesn’t. A patch of darker soil can trick a laser altimeter into thinking the ground is farther away—or doesn’t exist at all. So, the lander keeps descending…

blindly. Until it’s too late.

This isn’t speculation. Experts have watched it happen in real time.

Some say it’s as if the Moon is playing tricks—creating optical illusions, confusing the instruments designed to measure distance, slope, and position. These are not just bugs. These are systemic blind spots.

And the scary part? We’re not learning from our mistakes.

Every crash is followed by a press release: “Valuable data collected.” “Great progress.” But where’s the real change?

Many of these landers are operating on outdated logic trees: “If this, then that.” A line of code doesn’t improvise. It doesn’t question a false reading. It obeys.

Humans don’t.

When Armstrong saw that crater, he didn’t wait for confirmation. He acted. Our current spacecraft don’t have that freedom. They just trust their instruments, even when those instruments are being deceived by

lunar dust and light.

So, is the problem our tech?

Not exactly.

The real issue is how we design it. We’re building landers that are brilliant in theory—on paper, in simulators, in vacuum chambers. But the Moon isn’t a controlled lab. It’s a wild, reflective, unpredictable mirror.

And we keep making the same fatal assumption: that more precision = more success.

But the Moon doesn’t reward precision. It punishes rigidity.

And then… something changed.

In 2025, a private company named Firefly Aerospace sent its lander, Blue Ghost, to the Moon.

Everyone held their breath.

But Blue Ghost didn’t crash.

It landed.

Smoothly. Quietly. Safely.

What did they do differently?

They gave their machine eyes. And more importantly, they gave it a brain that knew how to use them.

Blue Ghost wasn’t just guided by numbers. It was guided by vision-based AI, trained to read the lunar surface the way a pilot might. It saw slopes, rocks, shadows. It recognized danger—and moved. It didn’t follow

code. It understood context.

This wasn’t just a technical shift. It was philosophical.

Where others built machines that obeyed, Firefly built a machine that could interpret.

Instead of relying on radar altimeters alone, Blue Ghost used real-time visual feedback to estimate depth and distance. When the sensors gave conflicting readings, it didn’t crash. It asked a deeper question: What

am I really seeing?

This is what modern autonomy lacks: awareness.

Tesla doesn’t drive based on GPS alone. It uses cameras. Context. Judgment.

So why are we sending billion-dollar landers to the Moon with 2005 logic?

Because we’re trapped in legacy.

Most current missions were planned years ago. The tech is baked in. The timelines are tight. The politics are brutal. Changing direction isn’t just hard—it’s seen as failure.

So, companies launch, knowing they’re flying blind.

The result? A Moon littered with broken dreams, shattered tech, and excuses wrapped in optimism.

Even Firefly, the one company that got it right, is now heading toward public markets. The risk? That its agile, innovative culture will be swallowed by investor expectations, safety protocols, and fear of failure.

In other words: the same system that got us here.

Because this isn’t really a Moon problem.

It’s an Earth problem.

It’s our obsession with repeatability over adaptability. Our refusal to question old paradigms. Our tendency to treat new challenges with old tools.

And the Moon?

It reflects all of it—literally.

So what’s the solution?

We need to stop designing machines that just land. We need to build explorers that learn. Machines that see, adapt, and decide.

Because the Moon isn’t going to change.

We are. Or we don’t land.

News

The Man Who ‘Discovered’ Troy Just Admitted the Truth… And It Destroys Everything You Thought You Knew

🏛️ The Man Who ‘Discovered’ Troy Just Admitted the Truth… And It Destroys Everything You Thought You Knew 😱📜 In…

Scientists Finally Solved the Antarctica Human Remains Mystery… And What They Found Buried in the Ice Will Terrify You

🧊 Scientists Finally Solved the Antarctica Human Remains Mystery… And What They Found Buried in the Ice Will Terrify You…

“‘It’s Happening Sooner Than I Expected…’ Graham Hancock STUNS Joe Rogan With Olmec Revelation!”

🧠🗿 “‘It’s Happening Sooner Than I Expected…’ Graham Hancock STUNS Joe Rogan With Olmec Revelation!” 🌍⚡ In a moment that…

‘I Saw the Plane Burning!’ Oil Rig Worker Reveals the Truth About MH370 — And It Changes Everything

✈️🔥 “‘I Saw the Plane Burning!’ Oil Rig Worker Reveals the Truth About MH370 — And It Changes Everything 😱💥”…

Not Just Statues – A Factory of Death: What They Found Inside the Terracotta Army Will Haunt You Forever

🏺🚫“Not Just Statues – A Factory of Death: What They Found Inside the Terracotta Army Will Haunt You Forever 💔☠️”…

The Study No One Was Allowed to Enter | Stan Laurel’s Death Mystery SOLVED — And It’s Darker Than You Think

🧳 “The Study No One Was Allowed to Enter 😳 | Stan Laurel’s Death Mystery SOLVED — And It’s Darker…

End of content

No more pages to load