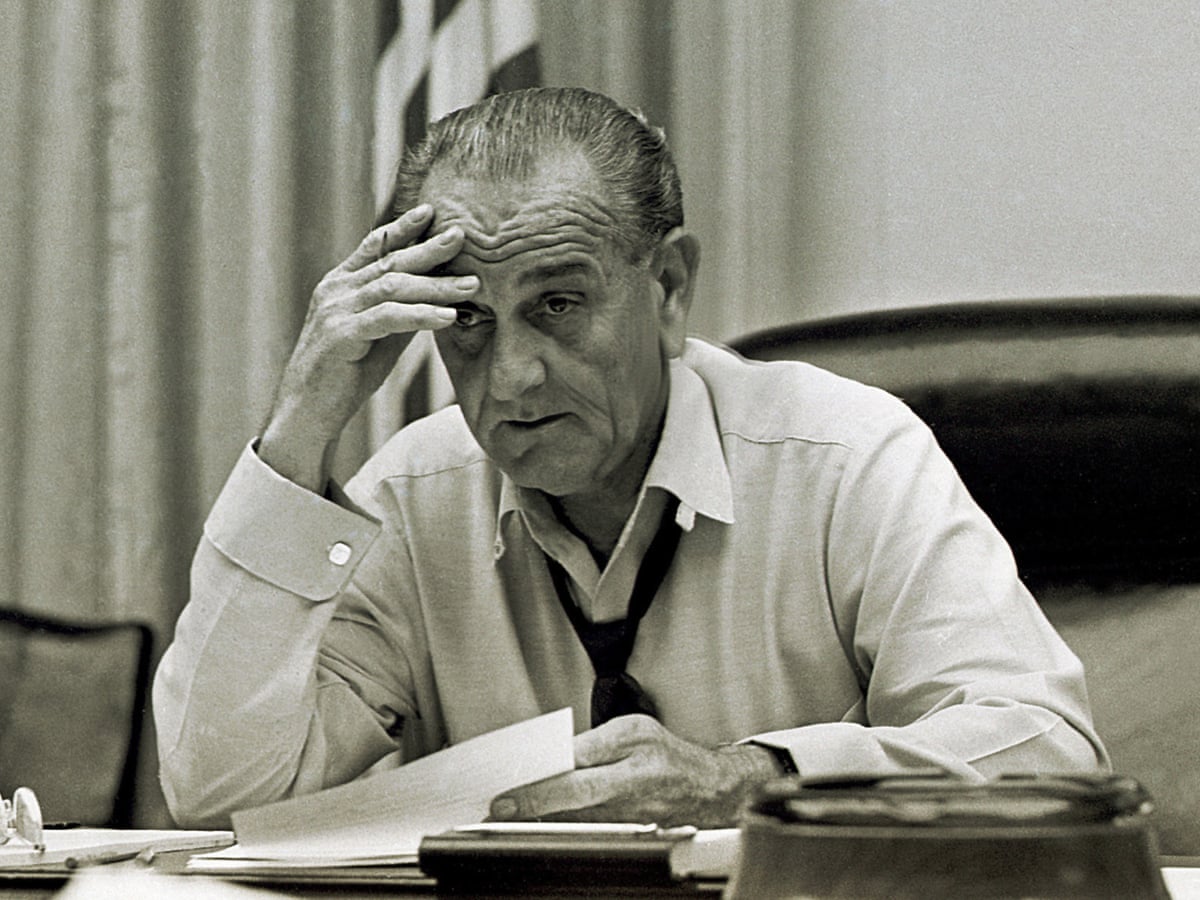

Lyndon B. Johnson lived in a world where every gesture was measured, every word recorded, and every weakness buried beneath the machinery of power.

From his earliest days as an ambitious Texas congressman to his ascent as President of the United States, Johnson cultivated an image of relentless strength, of a man who bent others to his will through sheer force of personality.

Yet behind that public armor existed a private dependence, a space where his bravado softened and his certainty fractured.

That space belonged, for a quarter of a century, to Alice Glass.

She was not the kind of mistress history usually remembers.

She did not linger on the fringes of scandal columns or emerge in courtroom testimonies.

She remained invisible by design, her influence woven quietly into the fabric of Johnson’s rise.

Alice Glass came from Marlin, Texas, a small town that offered little hint of the extraordinary life she would eventually lead.

She was educated, perceptive, and strikingly composed, qualities that followed her when she moved to Austin and began working as a secretary to a state senator.

Those who met her remembered her presence before her words: tall, elegant, and calm in a way that commanded attention without demanding it.

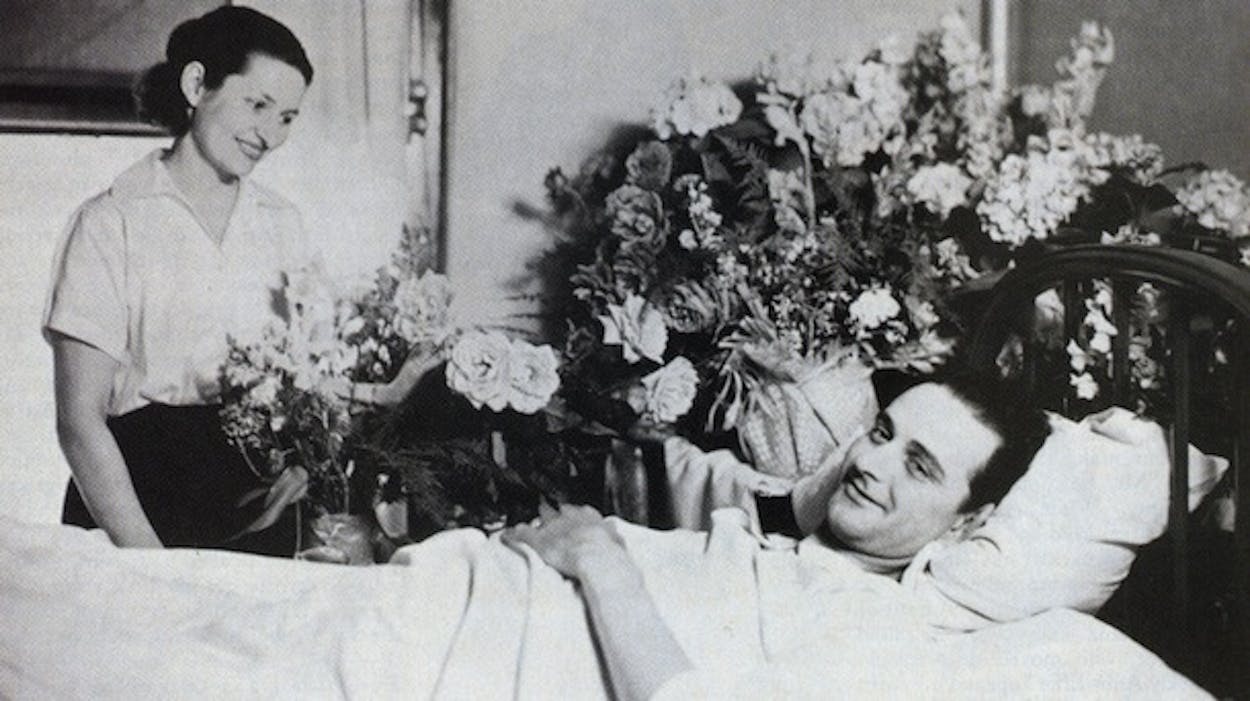

In 1931, her life shifted when she met Charles E.

Marsh, a wealthy publisher whose resources could buy almost anything except the devotion he sought.

Marsh adored Alice, building an estate for her in Virginia and surrounding her with luxury, but even as she accepted his generosity, she remained emotionally guarded, her ambitions reaching beyond comfort alone.

It was at Marsh’s estate that Alice encountered a young Lyndon B.

Johnson, a congressman whose hunger for significance was impossible to miss.

Johnson was not yet the domineering figure Washington would come to fear.

He was restless, eager, and deeply insecure, measuring himself against the men around him and constantly wondering whether he truly belonged among them.

Alice sensed something different in him.

She later remarked that she believed she had found a politician whose dreams were for others rather than for himself, a man whose ambition seemed tethered to a larger purpose.

That belief would bind her to him long after reality began to contradict it.

By 1938, their affair had begun, quietly and deliberately, a private flame sheltered from the glare of public life.

What made their relationship unusual was not merely its longevity, but its depth.

Alice was not simply a romantic escape for Johnson.

She became his confidant, his advisor, and, in moments of doubt, his refuge.

When Charles Marsh was away, Johnson spent extended periods at the estate with Alice, discussing politics, strategy, and the anxieties he rarely revealed elsewhere.

When Marsh was present, Johnson arrived with his wife, Lady Bird Johnson, in an unspoken arrangement that preserved appearances and maintained the careful balance of secrecy that defined their lives.

Those who observed them socially described their discretion with awe.

Nothing about their behavior hinted at intimacy.

Yet beneath that restraint flowed a connection that shaped Johnson’s development in ways history has only recently begun to acknowledge.

Alice introduced him to music, culture, and a sense of refinement that Washington demanded but Texas had not required.

She advised him on how to dress, how to speak, and how to present himself in rooms where power was exchanged through subtle cues rather than blunt force.

In a city obsessed with image, her guidance mattered.

More importantly, she listened.

Johnson, for all his dominance, was riddled with self-doubt.

He feared failure, obscurity, and the possibility that his efforts would never be enough.

With Alice, he could voice those fears without consequence.

Biographers later noted that while Johnson had numerous affairs, none appeared to influence his professional life in any meaningful way, except one.

Historian Robert Caro observed that this single, long-term relationship stood apart because Johnson relied on her political instincts and emotional steadiness, all while the public remained unaware of her existence.

She was valuable precisely because she could not be seen.

Their bond endured even after Alice married Charles Marsh in 1940, a union she reportedly resisted for years because she hoped Johnson would one day choose her openly.

Her sister would later say that Lyndon was the love of Alice’s life, a devotion so deep it bordered on overwhelming.

Letters passed between them for decades, carefully written and cautiously preserved, sustaining a connection that neither fully surrendered.

They were bound not by convenience, but by a shared history of whispered conversations and unspoken understanding.

As Johnson’s power grew, however, so did the distance between the man Alice loved and the man he was becoming.

The idealistic congressman transformed into a ruthless Senate leader and eventually a president burdened by decisions that would define a generation.

The Vietnam War marked the point of no return.

Alice was appalled by the conflict, seeing it not as a tragic necessity but as a moral failure of staggering proportions.

She held Johnson personally responsible, a judgment that cut deeper than any public criticism he faced.

Her response was not dramatic, but devastating in its finality.

Alice destroyed the letters Johnson had written to her over twenty-five years.

She wanted no trace of their relationship to survive, particularly not for her granddaughter, whom she did not want to know she had loved the man she believed was responsible for so much suffering.

This act of erasure was her final statement.

After dedicating nearly half her life to supporting, advising, and believing in him, she could no longer reconcile the man she once trusted with the president he had become.

Alice Glass died in 1976, taking with her a version of Lyndon B.

Johnson that history can never fully recover.

Her silence speaks volumes.

It reveals the emotional toll of loving a man whose public responsibilities eclipsed his private humanity, of being central to his inner world while remaining invisible to the nation he led.

For twenty-five years, she lived in the shadows of power, shaping it quietly and watching as it transformed the man she loved into someone she could no longer recognize.

What Alice ultimately said about Lyndon B.

Johnson was not delivered in interviews or memoirs.

It was spoken through absence, through burned letters and withdrawn devotion.

It was the judgment of a woman who had seen him at his most vulnerable and concluded that the cost of his choices was too great to forgive.

In that silence lies a haunting truth about power, intimacy, and the private consequences of public decisions.

History remembers Johnson as a president, a reformer, and a wartime leader.

Alice Glass remembered him as a man, and in the end, that memory was something she could no longer bear to keep.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load