The story begins, as so many dangerous stories do, by accident.

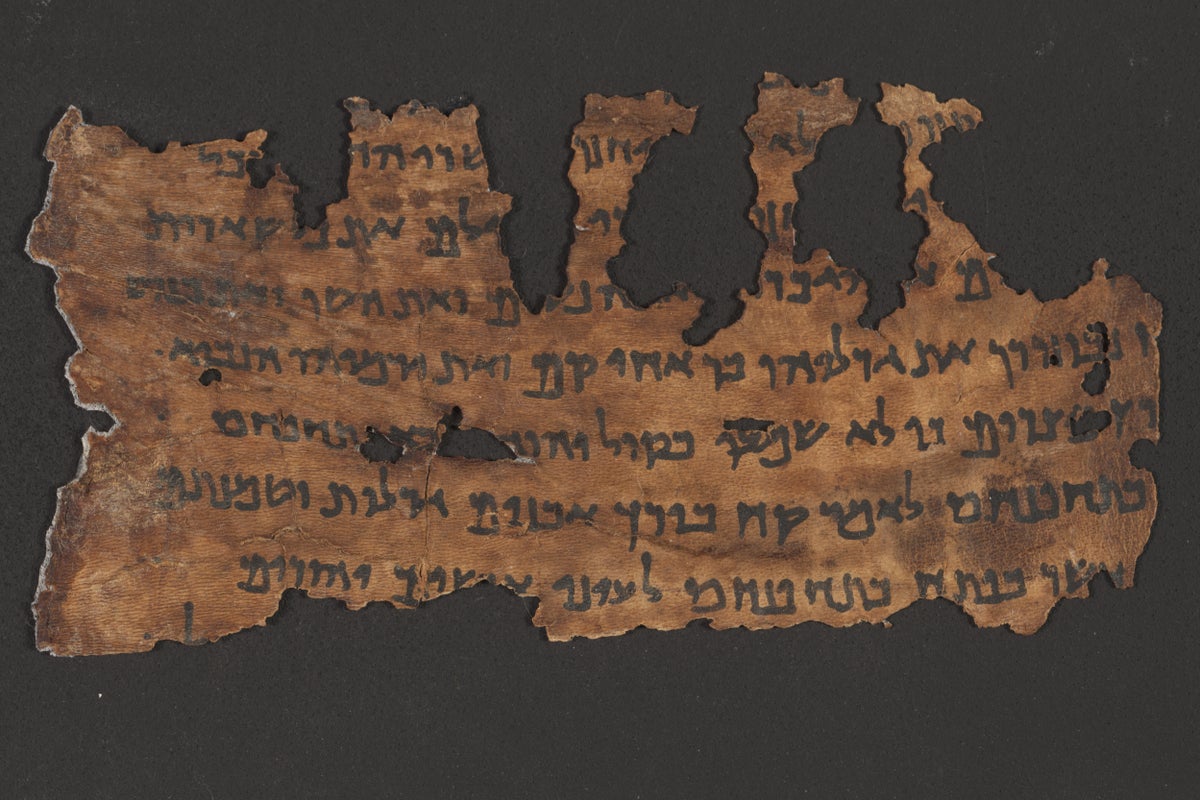

In the late 1940s, a Bedouin shepherd threw a stone into a cave near the Dead Sea and heard pottery shatter.

That sound echoed far beyond the Judean Desert.

What followed was the most consequential archaeological discovery of the modern age: the Dead Sea Scrolls, a vast library of ancient Jewish texts hidden for nearly two millennia.

They contained the oldest known copies of the Hebrew Bible and dozens of mysterious writings that rewired everything scholars thought they knew about Judaism, early Christianity, and the intellectual world that produced both.

From the beginning, the scrolls were chaos wrapped in parchment.

Fragmented, decaying, written by unknown hands, scattered across political borders just as the modern Middle East erupted into war.

Some fragments went to Jordan.

Others to Israel.

Some disappeared into private collections.

Scholars argued not only over what the scrolls meant, but who had the right to touch them, publish them, or even see them.

For decades, a small academic elite controlled access.

Publication crawled.

Suspicion grew.

The scrolls became less an archaeological find than a battlefield.

The dominant theory, promoted by Father Roland de Vaux in the 1950s, claimed the scrolls belonged to a single Jewish sect—the Essenes—who lived communally at Qumran and hid their library as Roman legions approached.

It was neat.

It was elegant.

And it was wrong, or at least dangerously incomplete.

The texts contradicted each other.

The theology splintered.

The archaeology refused to cooperate.

But without better tools, scholars were trapped inside their own assumptions.

Then technology arrived, quietly at first.

High-resolution photography.

Multispectral imaging.

Digital archives that allowed anyone, anywhere, to zoom into parchment fibers and ink residue invisible to the naked eye.

Words long thought erased reappeared like ghosts.

But even this wasn’t enough.

The real problem wasn’t reading the scrolls.

It was time itself.

When were they written? By whom? And how close were they to the original authors?

Radiocarbon dating offered estimates, but at a cost: destruction of precious material and error margins spanning generations.

Paleography—dating by handwriting style—was elegant but subjective, built on scholarly intuition rather than certainty.

A scroll could be placed somewhere between 150 BCE and 50 CE, a window wide enough to swallow history whole.

For decades, that vagueness was accepted as the price of ancient knowledge.

Then artificial intelligence changed the rules.

Around 2020, researchers began training AI systems on scrolls already dated by radiocarbon testing.

One system, ominously named Enoch, learned not just letter shapes but micro-details: stroke angles, spacing, pressure patterns left by hands dead for thousands of years.

It didn’t guess.

It measured.

When tested, Enoch dated manuscripts with an accuracy of about thirty years—an order of magnitude more precise than human paleography.

The first shock came quietly.

The Great Isaiah Scroll, the crown jewel of the Dead Sea Scrolls, was revealed to have been written by not one scribe but two.

Human experts had missed it for seventy years.

The AI saw the seam instantly.

That moment shattered a comforting illusion: if machines could see what generations of specialists could not, how much of the past had been misread?

Then the earthquake hit.

For decades, scholars believed scribal handwriting evolved neatly over time—from Hasmonean to Herodian styles.

Enoch proved they coexisted.

The styles overlapped completely.

Dating entire texts based on handwriting style collapsed overnight.

Hundreds of academic conclusions instantly became unstable.

Entire chronologies had to be rebuilt from scratch.

But the real panic came next.

As the AI analyzed more fragments, it began detecting patterns that weren’t linguistic at all.

Mathematical structures embedded in text layouts.

Repeating sequences.

Numerical relationships too precise to be random.

At first, researchers dismissed it as noise—machines hallucinating meaning.

But the patterns persisted across different scrolls, scribes, and centuries.

Some resembled error-correcting codes used in modern computing.

Others aligned with astronomical cycles.

This was where the line between scholarship and heresy blurred.

Ancient Jewish communities, particularly those associated with Qumran, were obsessed with the cosmos.

They followed a solar calendar.

They wrote extensively about stars, angels, and heavenly order.

That alone wasn’t shocking.

But one fragment described a solar disturbance so specific it resembled a coronal mass ejection—an event not scientifically documented until the Carrington Event of 1859, which shut down telegraph networks across the world.

Either the scribes witnessed a massive solar storm lost to all other records—or the text was metaphorical, poetic, misunderstood.

Academia leaned heavily toward metaphor.

The public did not.

Once the story escaped journals and entered headlines, it mutated.

Claims of ancient advanced knowledge exploded across the internet.

Scholars suddenly found themselves defending nuance against conspiracy, while simultaneously fighting their own colleagues.

Meanwhile, the most destabilizing discoveries were happening quietly, deep inside biblical texts themselves.

AI analysis of fragments from the Book of Daniel dated them precisely to the mid-2nd century BCE—exactly when secular scholars long argued the book was written.

Not centuries earlier, as tradition claimed.

This meant the fragments might be near-original compositions, not later copies.

For believers who viewed Daniel as prophetic scripture written long before the events it describes, the implications were devastating.

The machine had confirmed the critical consensus with brutal efficiency.

Ecclesiastes followed.

Traditionally attributed to King Solomon, AI dating placed its fragment firmly in the Hellenistic period.

The philosophical tone, once debated, now had a timestamp.

The text was brilliant—but it wasn’t Solomonic.

For some, this was a scholarly footnote.

For others, it was an existential crisis.

The deeper AI dug, the clearer something uncomfortable became: the biblical text was fluid in antiquity.

Different communities preserved different versions.

Passages appeared and vanished.

What later tradition would declare fixed had once been negotiable.

Sacred certainty was a later invention.

Institutions reacted predictably.

Some embraced the technology cautiously.

Others moved to contain it.

The Israel Antiquities Authority announced oversight on AI research.

Critics called it censorship.

Supporters called it protection.

The Vatican watched silently while funding its own internal AI projects.

Museums worried.

Donors panicked.

And then the forgery crisis detonated.

AI tools exposed dozens of modern fake Dead Sea Scroll fragments sold for millions to museums and universities.

Entire collections collapsed overnight.

Reputations were destroyed.

The antiquities market trembled.

Suddenly, AI wasn’t just rewriting history—it was threatening livelihoods.

The war turned personal.

Conferences devolved into shouting matches.

Careers ended.

Emails leaked.

Scholars accused each other of incompetence, bias, or betrayal.

Believers sent threats.

Conspiracy theorists sent worse.

And through it all, the scrolls kept yielding data, indifferent to human discomfort.

In 2024, AI analysis suggested textual links between Qumran writings and the New Testament, hinting that early Christian authors may have directly encountered these materials.

For historians, this was revolutionary.

For religious conservatives, it was unacceptable.

The battle lines hardened.

At its core, this is not a fight about scrolls.

It is a fight about authority.

For centuries, knowledge meant human expertise—languages learned, manuscripts touched, intuitions honed over lifetimes.

Now machines see patterns humans physically cannot.

But they cannot explain them in human terms.

When an AI dates a text, it offers results without narrative.

No story.

No tradition.

Just probability.

And that terrifies people.

Because once we accept that machines can read the past more accurately than we can, history stops being a comforting inheritance and becomes a dataset—cold, precise, and unforgiving.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were hidden because their authors feared the future.

They believed their world was ending.

They sealed their words away, hoping someone, someday, would be worthy of them.

That day has arrived—but not in the form they imagined.

The scrolls are speaking again.

Not through prophets.

Not through priests.

But through machines.

And what they’re telling us is simple, brutal, and impossible to ignore: history was never as stable as we pretended—and now, it can no longer hide.

News

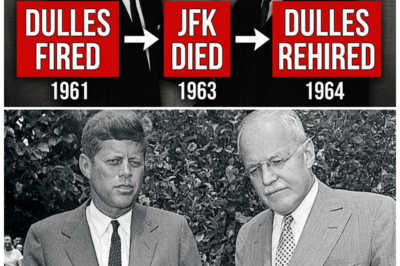

🕵️♂️💀 JFK Fired Him—Then He Investigated JFK’s Murder: The Dark Power Play of Allen Dulles

On November 29, 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson stood before the nation, his voice steady, his expression grave, and announced…

💥The Moment Eisenhower Silenced Montgomery: The Secret Power Struggle That Nearly Shattered the Allies

The air in Montgomery’s tactical headquarters that August morning felt heavy with the kind of confidence that breeds inevitability. The…

🧠 Google’s Quantum AI Was Asked Who Created Reality—Its Answer Was Not Human

The question itself is deceptively simple. Who built the universe? Not what caused the Big Bang. Not how matter behaves….

🗿 AI Decoded Stonehenge—and What It Was Built to Do Is Far More Disturbing Than a Temple

Stonehenge has always been framed as a mystery of effort. How did Neolithic people move stones weighing up to forty…

🕳️ A Vast Void Beneath the Pacific? New Seismic Scans Reveal a Structure Too Big to Ignore

Deep beneath the Pacific Ocean, far below the seafloor and far beyond any drill bit humanity has ever lowered, earthquake…

⚓ “Frozen in Time”: What a Classified Submersible Found Inside the USS Juneau Shocked Even the Navy

The USS Juneau was sunk in November of 1942 during the Battle of Guadalcanal, struck by a Japanese torpedo and…

End of content

No more pages to load