The Apollo program was supposed to be America’s redemption arc, a technological resurrection after the humiliation of Sputnik and the relentless pressure of the Cold War.

By 1967, the Moon was no longer just a dream; it was a deadline.

Schedules tightened.

Expectations hardened.

Failure was no longer an option—it was an embarrassment.

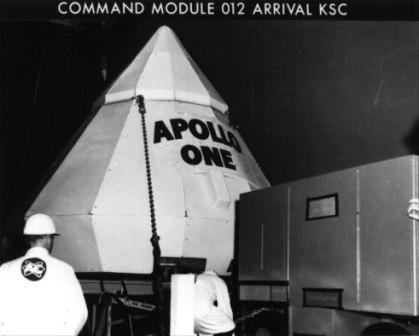

Inside that atmosphere of urgency, Apollo 1 took shape not just as a spacecraft, but as a symbol.

Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee were not merely astronauts; they were the public face of national resolve, strapped into a machine that promised history.

On the evening of January 27, 1967, the launch pad at Cape Kennedy was calm, almost routine.

The test was labeled “plugs-out,” a dress rehearsal without fuel, without countdown pressure, without danger—or so everyone believed.

Inside the command module, however, the air itself was waiting.

The cabin was filled with pure oxygen, pressurized above normal atmospheric levels.

It was a design choice inherited from earlier programs, one that had been questioned quietly but never challenged loudly enough to stop it.

In that environment, fire did not creep.

It exploded.

At 6:31 p.m., a crackle cut through the communications loop.

A brief sound.

Then urgency.

“Fire in the cockpit.

” Within seconds, the oxygen-fed flames tore through nylon netting, Velcro strips, wiring insulation—materials that had never been meant to survive in a pure oxygen world.

The heat surged so violently that pressure built faster than the capsule could release it.

The hatch, designed to open inward, became a sealed verdict.

Ed White reached for the handle.

Investigators would later find it partially turned.

Proof that he tried.

Proof that procedure failed him.

Outside, technicians heard shouting.

Then silence.

Smoke poured from the capsule seams.

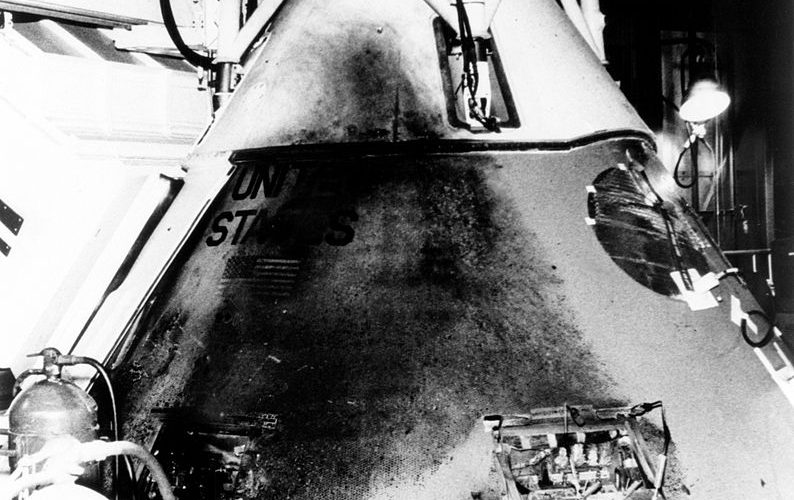

When the hatch was finally forced open minutes later, the interior was unrecognizable—blackened, melted, stripped of life.

Medical examinations would confirm a detail that still haunts the record: the astronauts did not die from burns.

They suffocated.

The oxygen that was supposed to keep them alive became the instrument of their deaths.

For years, NASA spoke carefully about what happened next.

The Apollo 204 Review Board produced thousands of pages, dense with engineering language.

But buried within those findings was a devastating conclusion that NASA has only recently stated without euphemism: the Apollo 1 fire was preventable.

It was not caused by a single spark, but by a chain of decisions—each one tolerated, rationalized, waved through in the name of progress.

Frayed wiring beneath Gus Grissom’s seat was identified as the most likely ignition source, though the exact wire could never be pinpointed.

That uncertainty became convenient.

What mattered more, the board found, was the environment NASA knowingly created.

Pure oxygen under pressure.

Extensive combustible materials.

Poorly routed electrical systems.

And perhaps most damning of all, a test classified as non-hazardous, meaning no firefighting teams stood ready, no emergency breathing equipment waited nearby, and no rapid extraction plan existed for a burning spacecraft.

Congressional hearings followed, and the tone was unforgiving.

Lawmakers demanded to know how the most advanced space agency on Earth could overlook such basic dangers.

NASA Administrator James Webb offered a chilling reflection: everyone knew astronauts might die someday, but no one imagined it would happen on the ground.

That statement, meant as an expression of shock, instead exposed the agency’s blind spot.

Danger had been romanticized in flight, not rehearsed in preparation.

Behind the scenes, families absorbed the cost.

Wives became widows.

Children learned that heroism does not guarantee a return home.

One daughter would later recall being eight years old when her mother explained that her father was never coming back.

That quiet moment, far from the roar of rockets, captured the human consequence of institutional failure better than any report ever could.

NASA did not collapse under the weight of Apollo 1—but it did change.

The program was halted.

Redesign became unavoidable.

The inward-opening hatch was scrapped, replaced with a single outward-opening hatch that could be released in seconds.

Pure oxygen at high pressure was banned during ground tests.

Every material inside the capsule was scrutinized.

Wires were rerouted, shielded, documented.

Fire-resistant suits replaced nylon.

Safety offices were created with authority independent of schedule pressure.

For the first time, risk assessment was no longer optional—it was mandatory.

These changes delayed the Moon landing by nearly two years, a delay that once would have been unthinkable.

Yet when Apollo 7 finally launched in 1968, the mission unfolded without catastrophe.

The redesigned spacecraft worked.

And when Apollo 11 carried Neil Armstrong to the lunar surface the following year, it did so on the foundation built from Apollo 1’s ashes.

For decades, NASA framed Apollo 1 as a tragic lesson learned, but rarely as a cultural failure confronted.

That tone has shifted.

On later anniversaries, officials began speaking more plainly.

By the 55th anniversary, NASA openly acknowledged that the fire resulted from both technical flaws and management lapses—a convergence of overconfidence, complacency, and relentless deadline pressure.

It was an admission long delayed, but deeply significant.

Apollo 1 did not just change hardware.

It changed mindset.

The tragedy reshaped how NASA approaches risk, influencing everything from the Space Shuttle program to modern spacecraft design.

Every checklist, every safety review, every pause before launch carries the imprint of three men who never made it off the pad.

The fire that killed them burned for less than a minute.

The consequences have lasted for generations.

And now, at last, NASA has stopped pretending it was inevitable.

The agency has finally admitted what history has always whispered: Apollo 1 was not destiny.

It was a warning.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load