🚨 “It Shouldn’t Exist”: Mexico’s Colossal Stone Faces Just Revealed a Secret That Rewrites Ancient History 🗿⚡

It starts with a tremor that isn’t seismic so much as human: a vibration of boots, shovels, murmurs snapping off mid-sentence as the tarp peels back.

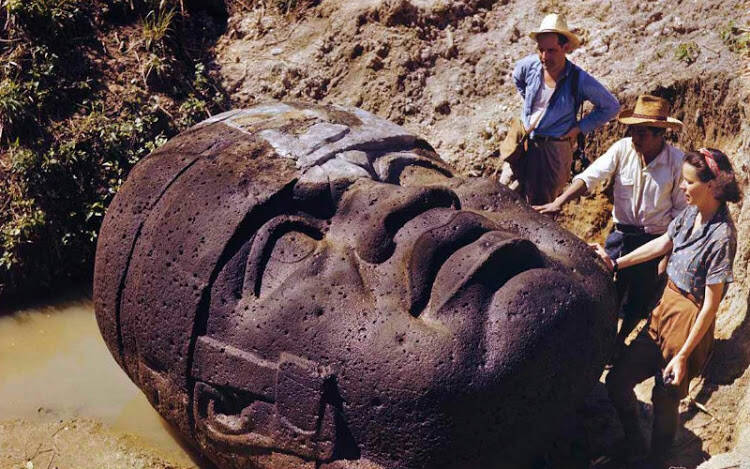

In the swamps and heat of southern Mexico—Veracruz and Tabasco, where water sits in the fields like glass and cicadas scream the hour—the earth has a habit of swallowing its own history and returning it in

pieces.

Farmers knew long before archaeologists got fancy about it that there were faces below their crops, basalt eyelids under the soil, watching.

They plowed around the brows, they joked about ancestors, they pointed them out to visiting cousins the way you might show off an old tree that survived ten storms.

But this time, the face that rolled into view was different.

The helmet carved down tight around the skull like a crown that’s also a sentence.

The cheeks heavy with intent.

The mouth neither cruel nor kind—simply unarguable.

There was a hush, the kind that eats even the birds.

Someone said, almost as a prayer, It’s another one.

Someone else whispered, No.

Look closer.

The weight hits you first.

Forty tons, sometimes more.

Basalt hauled from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas like a dare to gravity, floated on rivers, dragged over mud with a choreography of sweat and shouted orders.

The physics alone feels like an accusation; you with your cranes and calculus, explain this with your soft hands.

Then the features sharpen under the sun and it becomes personal.

The broad nose, the press of the lips, the eyes with their deep, exacting corners.

It’s not a god smiling down from a safe distance.

It’s a person looking back across 3,000 years as if last week were too long ago.

You can feel the old hierarchy gathering around you—workers with cords bitten into their palms, foremen aligning ropes, priests cutting smoke into the air, and somewhere a ruler who demanded not immortality

but recognition.

Remember me, the stone says without moving.

Remember that I moved mountains first.

San Lorenzo.

La Venta.

Tres Zapotes.

Names like coordinates sewn into the skin of Mesoamerica where the Olmec—mother culture to some, inconvenient origin story to others—built platforms and plazas, cut canals like signatures, lifted a clay

pyramid out of marsh as if to prove that mud could also be a throne.

The colossal heads were not isolated miracles; they were the punctuation to a sentence written in earthworks, ritual, and engineered water.

Imagine the mornings: mist hugging the causeways, the low thump of a rubber ball on a sacred court, drums thudding the ribs, the sudden hush of a decree.

Power had a sound back then, and it wasn’t subtle.

The stone doesn’t give you names.

There are no scrolls, no wind-whitened stelae telling you which king defeated which rival on a Tuesday in late spring.

The helmets might be battle gear or ballgame headdresses; the earspools might hum with rank.

But step closer—closer than comfort—and you notice the micro-decisions: a chisel’s hesitation at the corner of a mouth, a wedge knocked too deep and then redeemed.

The intimacy of labor becomes the biography you didn’t ask for.

Somewhere, a sculptor with wrists of cord and patience like a religion negotiated this face out of raw basalt using hammerstones, obsidian flakes, grit and water.

Every contour is a verdict.

Every plane is a vote for the possibility that art and command can be the same thing.

We love a mystery until it refuses to perform for us.

For decades the world projected obsessions onto these faces.

Early travelers muttered about strangers from across the sea, as if the Atlantic were a hallway and not a hazard.

Later, others saw defiance and ancestry coded in lips and noses, a reclamation written against the grain of colonial dismissal.

The helmets became spacecraft to some, the features proof of a voyage to others, Atlantis to still others, because the scale of the stone seemed to demand a theory equally enormous.

The human brain is a theater that hates empty stages; when facts sit out, speculation improvises.

But the dirt is patient.

It keeps receipts.

Under the roots and humidity, evidence gathers like a second script.

Quarry scars in the mountains where the basalt was bitten free.

River landings smoothed by use and time.

Ramps hardened with clay and crushed stone.

Workshop floors where chips still rest like commas in a paragraph mid-draft.

Half-shaped blocks abandoned mid-brow when politics changed or a ruler’s pulse stopped too soon.

Heads that were re-carved—old faces erased, new faces asserted—because power is never finished speaking.

The new find—the one that made grown scientists stand with their mouths open like children who’ve finally seen the magician’s left hand—came with something we were told not to hope for: context, heavy as the

head itself.

A string of postholes in alignment like a sentence diagram.

Burned resin in a shallow basin that still ghosted the air with ritual.

A trench that kissed the edge of a platform and then turned, precise as grammar.

And there, nested in mud and straw hardened to a fossil of labor, a bundle of tools like a sculptor’s pocket turned inside out: river-worn hammerstones, gritty abrasives, a greenish flake of jadeite sharper than an

insult.

No inscriptions.

But a voice, clear as a strike on stone, saying We did this.

We, not visitors.

We, not phantoms.

We, not your wishful foreigners.

It shouldn’t exist, say those whose timelines prefer straight lines over switchbacks—this competence, this scale, this order rising from swamps and heat without the anchoring comfort of iron or the wheel.

But human genius is not a franchise.

It appears where necessity clubs imagination over the head and drags it into daylight.

Corn, beans, squash—calories enough to free hands for building.

A river willing to be convinced into service.

An ideology that fused sovereignty to spectacle so completely that carving your own likeness into a 40-ton boulder felt less like vanity and more like infrastructure.

Does that erase the longings that cluster around the faces like moths to a porch light? Not at all.

Stand there long enough and you will feel the tug of the old romances: oceans crossed on reed boats, maps older than memory, a handshake between continents that textbooks forgot to mention.

You’ll hear the name of a Norwegian who proved a raft can seduce distance, the drumbeat of a thesis that insisted Africa’s hand reached west before chains ever did, the hum of diffusionism—sometimes generous,

often condescending—arguing that brilliance must always be an import.

The colossal heads listen without blinking.

They have heard worse.

They have been called gods, athletes, emperors, aliens, survivors of floods.

They have been dug up, paraded, reburied, and framed by museum lights that flatten their menace into polite awe.

And still they keep doing what they were made to do: occupy the center of a plaza and refuse to be ignored.

The newest head—mud fresh, features clean as a verdict—wasn’t alone.

The ground around it coughed up fragments that read like stage directions.

A broken throne with ropes carved in relief, as if authority itself could be tethered and led.

An altar face whose mouth opened onto a cave, ruler emerging like a storm breaking the line of the horizon.

Tiny figurines with infant faces, downturned mouths, a seriousness that feels older than language.

A cache of rubber balls hardened into misshapen moons.

You begin to see it not as a collection of artifacts but as a system, a grammar of rule.

The ruler is athlete, warrior, priest.

The plaza is stadium, temple, court.

The ceremony is not spectacle alone but governance—taxation converted into stone and smoke, labor transformed into myth, obedience elevated into choreography.

The head is the punctuation mark that makes the sentence impossible to misunderstand.

This is how you anchor a people.

This is how you make tomorrow answer to today.

And still the questions insist on slipping their fingers under the door.

How far did ideas travel? How many hearts learned to beat to the same ritual drum across valleys and coasts? We find echoes in the Maya, later in the Aztec, in the way courts were lined, balls were hurled, kings

were dressed and undressed by ceremony.

Lineages do not require ownership to establish kinship.

You can inherit a gesture without inheriting a name.

You can learn a way to be powerful just by watching the neighbors’ smoke rise higher than yours.

The jungle pretends it is indifferent, but it isn’t.

When the winch groaned and the head lifted, there was a sound like rain about to arrive.

A vulture traced a slow comma overhead.

The field team took off their gloves and pressed fingers to the carved cheeks because sometimes the only peer review that matters is the human impulse to touch the past and be touched back.

A young technician cried—quietly, efficiently, as if not to disturb the stone.

An older archaeologist laughed in that half-broken way people laugh at funerals when someone tells a joke too true to be kind.

Everyone waited for the head to offer a clue, a compromise, a slip of confession.

Stone does not bargain.

It only endures.

Here is the part that stings: the discovery doesn’t soothe the debates; it sharpens them.

The tools and postholes tilt the scale toward local genius, yes, but the faces continue to invite projection because that is their other power.

They are mirrors with opinions.

If you arrive hungry for connection across seas, you will find a wave in the curve of the lip.

If you come armored in skepticism, you will count chisel marks like votes.

If you need the comfort that history is a straight road, you will hate the switchback that these heads represent.

If you crave the vertigo of being small next to something made by hands no better than yours, you will get your wish.

We want the reveal, the moment when a camera pans and the narrator finally names the secret.

Instead, we get something harder and more honest: the revelation of work.

Not a miracle.

A procedure.

Stones released from a mountain’s grip.

Rafts disciplined to the river’s mood.

Ramps and rollers folding distance into a solvable problem.

Bodies—so many bodies—leaning into ropes with the private hopes of public ritual beating in their chests.

The heads are not the proof of a visit from elsewhere; they are evidence of what a society can do when it decides to turn its will into an object.

The silence after the lift is the best part.

Phones down.

Not even a breeze.

In that pause the jungle is an audience, and the face is a stage, and you are, briefly, the understudy for a role you do not deserve.

You feel the truth arrive with the weight of weather: the past is not asking your permission.

It does not need you to like it, fix it, or fold it into your favorite theory.

It merely requires you to witness.

And once you have, you are responsible for what you choose to say next.

So what changes with this discovery? Maybe not the coordinates on a map.

Maybe not the chronology in a textbook.

What changes is the aperture through which we look.

The new head, with its workshop’s confession and its plaza’s geometry, narrows the room for fantasies that erase the people who bled to make it.

It also widens the room for wonder where it belongs: not in the myth of foreign saviors, but in the measurable, muscular brilliance of a culture that organized a landscape into obedience and carved its leadership

into permanence.

The faces will keep staring.

The jungle will keep pretending indifference.

Rivers will continue to remember the taste of stone.

And we—newcomers in every century—will continue to trip over our own need to make the past about us.

But if we are lucky, now and then the earth will hand us a head and a handful of tools, and the silence after the reveal will be loud enough to hear the only story that was ever true: They were here.

They were extraordinary.

And they did not wait for permission to prove it.

News

Track 61: The Underground Passageway for Celebrities and Presidents at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel! What Lies Beneath?

Track 61: The Underground Passageway for Celebrities and Presidents at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel! 😱🚪 What Lies Beneath? New York…

50 Cent’s Savage Warning to Diddy’s Son: “You’re Playing With Fire!” – The Shocking Truth Behind Their Rivalry and the Fallout from Diddy’s Sentencing!

50 Cent’s Savage Warning to Diddy’s Son: “You’re Playing With Fire!” – The Shocking Truth Behind Their Rivalry and the…

Gillie Da Kid Drops a BOMBSHELL: Jay-Z’s Alleged “Slave Contract” EXPOSED! The Shocking Truth Behind Artist Manipulation and Control in Hip-Hop!

Gillie Da Kid Drops a BOMBSHELL: Jay-Z’s Alleged “Slave Contract” EXPOSED! The Shocking Truth Behind Artist Manipulation and Control in…

50 Cent Unleashes a Storm: “Diddy Will Meet His Old Friend Again” – The Shocking Truth Behind Their Turbulent Relationship and the Dark Secrets of Hip-Hop!

50 Cent Unleashes a Storm: “Diddy Will Meet His Old Friend Again” – The Shocking Truth Behind Their Turbulent Relationship…

Unbelievable! The Shocking Kidnapping of DJ Drama Revealed: How the Feds Attempted to Crush Hip-Hop’s Mixtape Revolution!

Unbelievable! The Shocking Kidnapping of DJ Drama Revealed: How the Feds Attempted to Crush Hip-Hop’s Mixtape Revolution! 🚨🎤 The saga…

New Evidence CONFIRMS Jay-Z Planned a HIT on Tupac! The Shocking Truth Behind Their Rivalry!

New Evidence CONFIRMS Jay-Z Planned a HIT on Tupac! 😱💥 The Shocking Truth Behind Their Rivalry! The rivalry between Jay-Z…

End of content

No more pages to load