The first reason strikes at the very heart of the official story: the timeline.

According to the Warren Commission, Oswald fired three accurate shots with a bolt-action Mannlicher-Carcano rifle in roughly six seconds, hitting a moving target while reacquiring aim between shots.

Even experienced marksmen have questioned whether this was physically possible under those conditions.

Oswald’s Marine rifle scores place him as average, not exceptional.

The required speed and precision stretch plausibility, not just for Oswald, but for almost anyone.

When a case depends on a near-superhuman performance, doubt is not conspiracy—it’s logic.

The second reason lies in the rifle itself.

The Mannlicher-Carcano was an outdated weapon, infamous for its stiff bolt and poor scope alignment.

Test firings conducted later required significant adjustments and produced inconsistent accuracy.

More troubling, the rifle allegedly linked to Oswald was not definitively proven to be his beyond disputed paperwork and questionable witness recollections.

Even the chain of custody surrounding the weapon raises red flags.

In a case of this magnitude, ambiguity is not a footnote—it is a warning sign.

Third, the physical evidence inside the Texas School Book Depository refuses to cooperate with the lone gunman narrative.

No one reported seeing Oswald firing from the sixth floor at the moment of the assassination.

No fingerprints conclusively placed him on the rifle at the time of the shooting.

Paraffin tests performed shortly after his arrest showed no gunpowder residue on his cheek, inconsistent with having fired a rifle.

These details were minimized, then buried beneath repetition of a conclusion already decided.

Evidence that contradicts a verdict does not vanish simply because it is inconvenient.

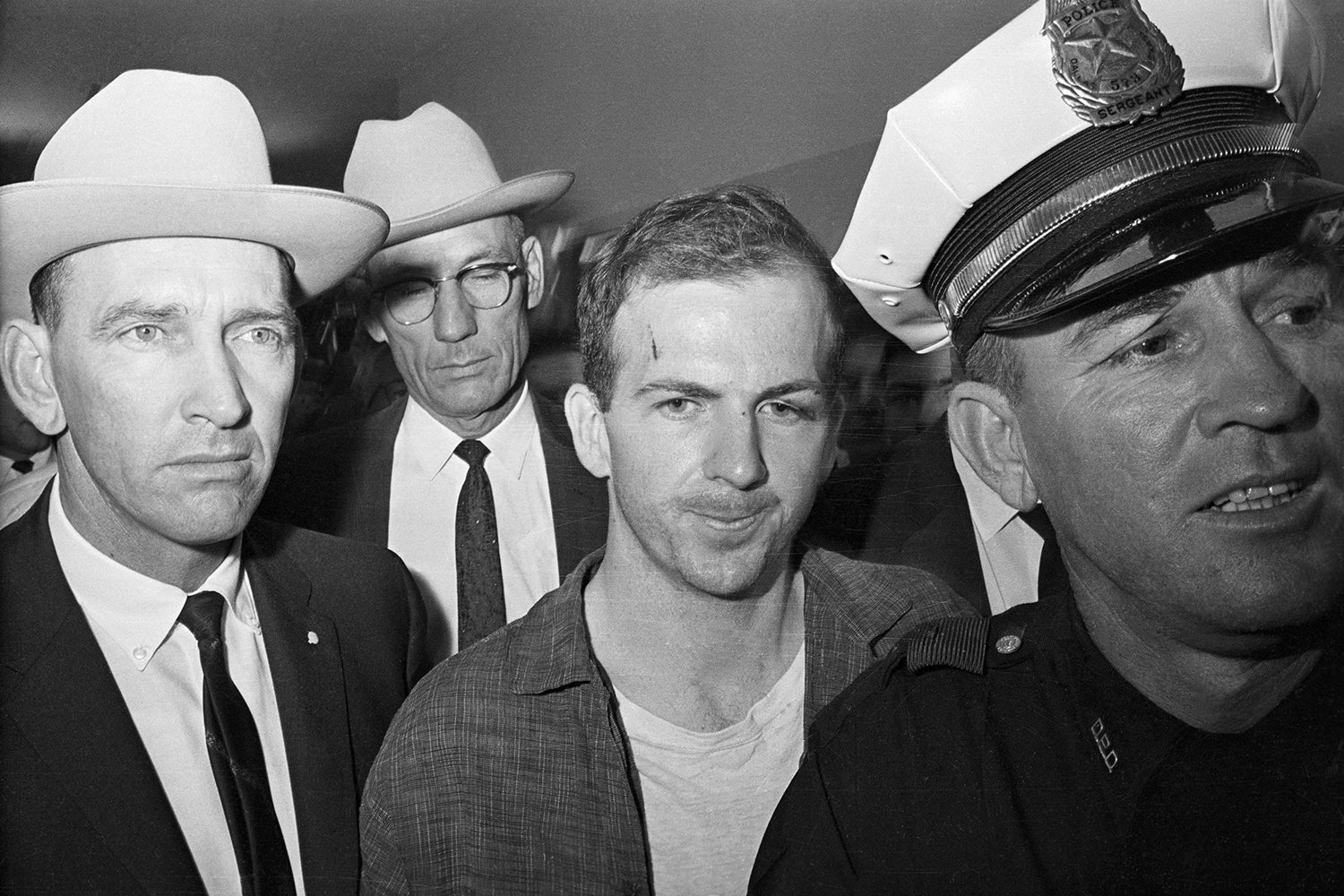

The fourth reason is Oswald’s behavior immediately after the assassination.

A guilty man on the run typically flees the city, discards weapons, and hides.

Oswald did none of that.

He calmly left the building, took a bus, then a taxi, and returned to his boarding house.

His movements suggest confusion, not escape.

When arrested, he denied killing the president and famously declared, “I’m just a patsy.

” These were not the words of a man reveling in infamy.

They were the words of someone who realized, too late, that the narrative had already closed around him.

The fifth reason emerges from witness testimony—specifically, how much of it contradicts the official account.

Multiple witnesses reported hearing shots from the grassy knoll, not behind the motorcade.

Others described seeing smoke or suspicious activity near the fence.

Police officers ran toward the knoll instinctively, not toward the Book Depository.

If Oswald acted alone from behind, why did so many people react as if the danger was in front of them? Collective confusion is one thing.

Collective misdirection is another.

Sixth, Oswald’s background reads less like that of a lone extremist and more like someone entangled in intelligence operations.

He defected to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, then returned to the United States with remarkable ease.

He associated with both pro-Castro and anti-Castro groups, an ideological contradiction that makes sense only in the world of infiltration and surveillance.

Intelligence agencies later denied interest in him—until documents revealed they had been tracking him closely.

This does not prove innocence, but it strongly suggests Oswald was not operating in isolation.

Pawns are often mistaken for kings.

The seventh and perhaps most devastating reason is this: Lee Harvey Oswald never stood trial.

He was silenced before evidence could be challenged, before witnesses could be cross-examined, before inconsistencies could be exposed under oath.

Jack Ruby’s murder of Oswald ensured that the official story would never face an adversarial test.

Justice requires process.

Without it, conclusions are not verdicts—they are assumptions.

And assumptions harden fastest when they serve political stability.

What emerges from these seven points is not proof of Oswald’s innocence, but something just as dangerous to official history: reasonable doubt.

The Warren Commission asked the public to accept improbabilities stacked on improbabilities, all while dismissing contradictions as coincidence.

Over time, repetition replaced scrutiny.

Oswald became a symbol, not a suspect.

Perhaps the most tragic element of Oswald’s story is how perfectly he fit the role assigned to him.

He was isolated, abrasive, politically confusing, and expendable.

He had no powerful defenders, no institutional protection, no time.

Once labeled the assassin, his humanity evaporated.

He became a container for national grief, anger, and fear.

That does not make him innocent.

But it makes him useful.

If Lee Harvey Oswald was innocent, even partially, the implications are staggering.

It means the truth was sacrificed for calm.

It means history was stabilized at the cost of accuracy.

And it means the real story of November 22, 1963, is still fractured—distributed across suppressed testimony, classified files, and unanswered questions that refuse to age out.

Oswald once said he was a patsy.

History laughed, then moved on.

But patsies are only obvious after the game is revealed.

Until then, they are indistinguishable from villains.

And six decades later, the case against Lee Harvey Oswald still asks for belief where it should demand certainty.

That alone is reason enough to look again.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load