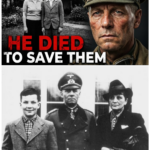

October 14, 1944 began quietly at the Rommel villa in Herrlingen.

Erwin Rommel was still recovering from the injuries he suffered when Allied aircraft strafed his staff car months earlier.

He walked with difficulty.

His left eye would not fully close.

But he was alive—and by late 1944, that alone had become intolerable to Adolf Hitler.

At noon, two generals arrived: Wilhelm Burgdorf and Ernst Maisel.

They did not come with sympathy or concern.

They came with an ultimatum already signed in Berlin.

Rommel met them privately for nearly an hour.

When he emerged, his face betrayed nothing.

He went upstairs and told his wife, Lucie, that she would soon be a widow.

Then he sat with his son Manfred, just fifteen years old, and explained the mechanics of his own execution.

Hitler had accused him of complicity in the July 20 plot.

Rommel had known some of the conspirators.

Whether he actively participated remains debated, but Hitler had made his decision, and Hitler’s decisions were final.

If Rommel took cyanide, the regime would announce his death as a consequence of war injuries.

He would receive a state funeral.

His family would be spared.

If he refused, Lucie and Manfred would be destroyed alongside him.

Gestapo agents waited outside.

This was not mercy.

It was theater.

At 12:15 p.m., Rommel told his son he had fifteen minutes left to live.

He put on his Afrika Korps jacket, took his field marshal’s baton, said goodbye, and walked to the car.

A short drive down the road.

A stop.

Cyanide.

At 12:35, the phone rang at the villa.

Erwin Rommel was dead.

The official cause would be listed as a brain embolism.

A teenage boy now carried one of the Third Reich’s most dangerous secrets.

Four days later, tens of thousands lined the streets of Ulm.

The coffin was draped in the Nazi flag.

Military bands played.

Field Marshal von Rundstedt praised Rommel’s loyalty to Führer and Fatherland.

Every word was a lie.

The regime that murdered him honored him publicly while privately erasing him.

Lucie and Manfred stood in silence, knowing that speaking the truth would mean death.

Rommel had taken the poison so they would not have to.

The war ended six months later.

In April 1945, as Allied forces swept through Germany, Manfred Rommel—now sixteen—was conscripted into the Reich Labor Service.

As the front collapsed, he deserted.

French forces captured him anyway.

Processed as a prisoner of war, he expected anonymity.

Instead, his name drew attention.

General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, commander of the French First Army, requested a personal meeting.

De Lattre had fought Rommel in North Africa.

He respected him as an enemy.

Now he wanted the truth.

Manfred could have repeated the official story.

He was a teenager, a prisoner, surrounded by victors.

Silence would have been safe.

Instead, he told everything.

The noon arrival.

The ultimatum.

The fifteen minutes.

The waiting Gestapo.

The phone call confirming death.

His testimony became one of the earliest firsthand confirmations that the Nazi regime forced suicides on its own officers.

A boy who should have been silent became a witness for history.

Released in August 1945, Manfred returned to his mother.

Germany lay in ruins.

Denazification courts examined everyone connected to the regime.

Families of generals faced suspicion and hostility.

Lucie Rommel said almost nothing.

For twenty-seven years, she lived in deliberate quiet.

She did not write memoirs.

She did not defend her husband publicly or attack his enemies.

She understood the danger of spectacle.

Silence was not denial—it was survival.

She raised her son, endured occupation and division, and let history speak for itself.

But the Rommel family carried another secret, one that would remain hidden for decades.

In 2001, a Sunday Times investigation revealed that Erwin Rommel had fathered a daughter in 1913, before his marriage to Lucie.

The child, Gertrud, was born to Walburga Stemmer, a fruit seller.

Rommel had proposed marriage, but his family objected.

The relationship ended.

The child did not disappear.

Gertrud was introduced as a cousin and maintained contact with the family throughout her life, visiting Lucie and Manfred even after Rommel’s death.

Walburga died in 1928, officially of pneumonia, though some historians suspect suicide.

The revelation complicated the Rommel myth.

The regime had crafted him not only as a military hero, but as a flawless family man.

Reality, as always, was messier.

Yet even this secret did not shatter the family.

Gertrud died in 2000, connected but never publicly acknowledged.

The Rommels did not erase her.

They protected her quietly, just as they protected the truth about October 14.

Lucie Rommel died in 1971, having watched her son grow from a traumatized witness into a man determined to live differently.

And this is where the story takes its most unexpected turn.

Manfred Rommel did not hide from his name.

He did not flee Germany.

In 1974, he ran for mayor of Stuttgart—and won.

He would hold the office for twenty-two consecutive years, becoming one of the most respected political figures in postwar Germany.

He did not trade on his father’s fame.

He inverted it.

Manfred championed immigrant integration when it was politically unpopular.

He built coalitions between government, businesses, and community organizations to support newcomers.

He defended dissent.

He promoted reconciliation.

His politics stood in direct opposition to everything the Nazi regime represented.

And then came 1977.

The Red Army Faction kidnapped and murdered industrialist Hanns Martin Schleyer.

When several RAF members later died in Stammheim Prison, no cemetery in Germany would accept their bodies.

Cities refused.

Families were left with nowhere to bury their dead.

Manfred Rommel authorized their burial in Stuttgart.

The backlash was immediate and ferocious.

Critics accused him of honoring terrorists.

Political opponents called it betrayal.

How could the son of Hitler’s most famous field marshal allow this? Manfred’s reasoning was simple: reconciliation requires acts of reconciliation.

The dead were dead.

Their crimes were over.

Someone had to end the cycle of hatred.

He was willing to take the blame.

It was exactly the decision his father’s regime would have despised.

And that was the point.

In 2014, Stuttgart made a decision unimaginable in 1945.

They renamed their airport—not after Erwin Rommel, the general of conquest—but after Manfred Rommel, the mayor.

The city stated that Manfred represented tolerance, openness, and reconciliation more than anyone else in its modern history.

Think about that transformation.

In 1944, the name Rommel symbolized Nazi military power.

Seventy years later, it symbolized democratic values.

Not because history forgot—but because someone chose differently.

Manfred Rommel died in 2013, one year before the renaming.

He was eighty-four years old.

He had spent his life proving that inheritance does not dictate destiny.

His father died under coercion.

His mother endured in silence.

And their son took a name forged in dictatorship and remade it into a rejection of everything that dictatorship stood for.

What happened to Rommel’s family after World War II was not disgrace or collapse.

It was transformation.

A forced suicide meant to silence became a truth revealed.

A widow’s silence became dignity.

A hidden daughter complicated a myth but did not destroy a family.

And a teenage boy who watched his father die chose, over seventy years, to make that name stand for something else entirely.

History remembers Erwin Rommel as a general.

But it remembers his family for something rarer: the ability to survive power without worshipping it, to carry history without repeating it, and to prove that even the darkest legacies can be reversed—not by forgetting, but by choosing differently.

News

Scientists Unwrapped an Egyptian Mummy—and Found a Fabric Humanity Wasn’t Supposed to Invent Yet ⚠️🧬

The tomb lay beneath a known burial shaft, detected only after microgravity imaging in 2023 revealed a rectangular void with…

They Looked Beneath Kailasa Temple—and What They Found Rewrites Ancient Engineering Forever 🕳️📜

High on India’s Deccan Plateau, carved directly into the black basalt cliffs of Maharashtra, the Kailasa Temple rises not as…

‘Get Out of My Office’: The Moment Eisenhower Broke Montgomery—and Redefined Power in World War II 💥🪖

Montgomery’s voice is calm, almost bored, as if he’s explaining an obvious truth to a slow student. Bradley is overwhelmed….

“You Don’t Look Like a General” 😳⚔️ The Muddy Moment Eisenhower Nearly Missed Patton at the Front

France in 1944 was not the clean, heroic battlefield of recruitment posters; it was a grinding, filthy organism that swallowed…

“He Wasn’t Just a Giant” 💔 The Princess Bride Cast Finally Tells the Truth About André the Giant

The first thing everyone remembers is the door. André René Roussimoff couldn’t enter a room without bowing to it, bending…

NASA’s Darkest Confession 🚨 The Truth About Apollo 1 They Hid for 55 Years

The Apollo program was supposed to be America’s redemption arc, a technological resurrection after the humiliation of Sputnik and the…

End of content

No more pages to load