When Sputnik launched, Eisenhower was not alarmed in the way the public wanted him to be.

He was a general who had planned invasions, measured enemy capability, and watched panic destroy rational strategy.

From a military standpoint, Sputnik changed nothing.

The Soviets already had missiles that could reach American cities.

A satellite overhead didn’t alter that reality.

Eisenhower said so publicly, and Americans hated him for it.

They wanted outrage.

They wanted vows.

They wanted a promise to beat the Soviets at their own game.

What Eisenhower understood—and what most of his critics did not—was that space was not just a race.

It was a domain that would shape international law, military balance, scientific cooperation, and national identity for generations.

Panic would produce waste.

Spectacle would produce mistakes.

If America rushed blindly into space, it would militarize the heavens and lose control of costs, purpose, and legitimacy.

Before Sputnik, the United States already possessed the raw ingredients of space power.

The Army, Navy, and Air Force were all developing rockets.

Missile programs doubled as space launch systems.

Scientists were working on satellites.

But everything was fragmented, competitive, and inefficient.

No unified vision.

No civilian leadership.

No single institution responsible for space.

Eisenhower had tolerated this fragmentation because space, until Sputnik, was a military afterthought.

Once the Soviets crossed the psychological threshold, that changed.

What Eisenhower did next was not loud, but it was revolutionary.

Instead of handing space to the Pentagon, Eisenhower made a decision that still defines American space policy today: space would be civilian-led.

This was not obvious.

In 1957, rockets meant missiles.

Space meant war.

Many in Congress wanted a military space command.

Eisenhower refused.

He feared an arms race in orbit.

He feared weapons circling the planet.

He feared turning space into the ultimate battlefield.

And he feared what that would do to American credibility when international rules inevitably emerged.

So he moved deliberately.

He appointed James Killian of MIT as his science adviser, elevating scientific expertise to the center of presidential decision-making.

He empowered civilian scientists over generals.

He began drafting legislation for a new agency that would take space out of interservice rivalry and put it under one roof.

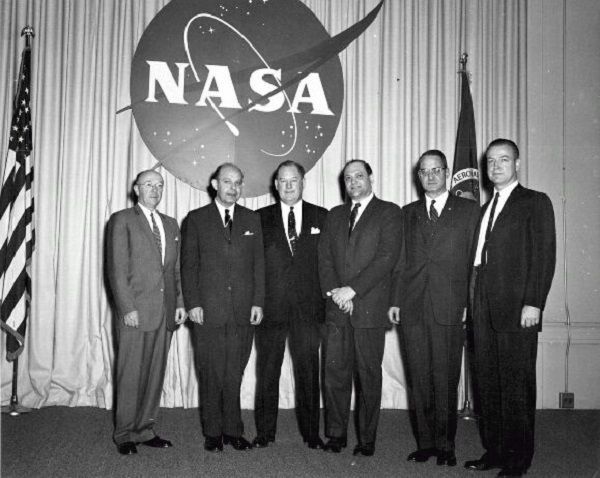

That roof would be called NASA.

In January 1958, Eisenhower publicly announced the plan.

In July, he signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act into law.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration absorbed NACA, pulled space projects away from the military, and established peaceful exploration as national policy.

This was Eisenhower’s design, his architecture, his restraint imposed on American ambition.

NASA officially began operations on October 1st, 1958—one year after Sputnik.

Eisenhower didn’t stop there.

He approved Project Mercury, America’s first human spaceflight program.

He authorized communications satellites, weather satellites, reconnaissance satellites.

He approved the early development of the Saturn rocket family—the very rockets that would later carry astronauts to the moon.

He recruited Wernher von Braun’s team into the civilian space effort.

He expanded budgets every year, though always reluctantly, always questioning cost.

This was Eisenhower’s way.

Build capability.

Avoid hysteria.

Ask hard questions.

Refuse symbolism for its own sake.

And that is exactly why he would lose the credit.

When Kennedy took office in January 1961, NASA already existed.

Astronauts were already selected.

Rockets were already under development.

The scaffolding of the space age was already standing.

Kennedy inherited a functioning space agency with momentum, infrastructure, and talent—all created under Eisenhower.

Then Yuri Gagarin went to space.

The Soviets beat America again.

And this time, Kennedy panicked.

Kennedy was young, new, and deeply sensitive to perceptions of weakness.

He asked his advisers a brutally simple question: what can we do first? Not what makes sense.

Not what advances science.

What can we win?

The answer was the moon.

Landing a man on the moon was not Eisenhower’s vision.

In fact, Eisenhower thought it was unnecessary, expensive, and driven by politics rather than purpose.

But it was dramatic.

It was measurable.

And it was inspirational.

On May 25th, 1961, Kennedy did what Eisenhower never would.

He drew a line in the future and dared the nation to reach it.

“Before this decade is out,” he said.

The words echoed.

The deadline electrified.

The goal unified.

NASA’s budget exploded.

The space program became a national crusade.

Contractors multiplied.

Facilities expanded.

Everything Eisenhower had built was now pointed at a single symbolic objective.

And it worked.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon in 1969, the moment belonged to Kennedy.

Kennedy’s speeches.

Kennedy’s deadline.

Kennedy’s dream.

Eisenhower was already dead, four months in the ground, his fingerprints invisible beneath the cathedral rising from his foundation.

History loves vision more than preparation.

It remembers poetry, not procurement.

Kennedy spoke of destiny.

Eisenhower spoke of budgets.

Kennedy pointed at the moon.

Eisenhower quietly ensured America could reach it.

NASA itself helped seal the narrative.

Cape Canaveral became Kennedy Space Center.

Apollo plaques honored Kennedy’s challenge.

The agency tied its greatest triumph to the man who inspired it, not the man who designed it.

Eisenhower never complained.

In interviews, he admitted he wouldn’t have gone to the moon at that cost.

He didn’t resent Kennedy’s ambition; he questioned its necessity.

Eisenhower measured success differently.

If the institution endured, the mission succeeded.

And it did.

The irony is stark.

Eisenhower, the general who warned about the military-industrial complex, built a civilian space agency to prevent militarization of space.

Kennedy, the civilian president, unleashed one of the largest government technology mobilizations in history.

Both were right in different ways.

Both were necessary.

But only one became legend.

Eisenhower created NASA because America needed it.

Kennedy transformed NASA because America needed to believe.

One built the foundation.

The other raised the cathedral.

History remembers the cathedral.

And somewhere beneath the launchpads, the rockets, the plaques, and the speeches, Eisenhower’s quiet architecture still holds the entire structure upright—unseen, uncelebrated, and indispensable.

News

Before the Blonde Bombshell: The Childhood Trauma That Never Left Marilyn Monroe 🕯️🌪️

Marilyn Monroe entered the world not as a star, but as Norma Jeane Mortenson, born on June 1, 1926, in…

Inside the Manson Family: How Love Turned Into Ritual Murder 😱🕯️

To understand what it was really like inside the Manson Family, you have to forget the image history gives you…

The Smile That Shouldn’t Exist: Why Albert Thomas Winked at LBJ After JFK’s Death 😳

The photograph exists. That is the problem. Not a rumor. Not a story passed down through whispers. A frame of…

Why Millions Believe the Government Didn’t Tell the Truth About JFK 😨

John F. Kennedy entered the White House as a symbol of optimism at a moment when America desperately wanted to…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

Don Johnson Left Patti D’Arbanville the Moment Fame Changed Him Forever 😱💔

Long before pastel suits and speedboats turned Don Johnson into the face of the 1980s, he was just another struggling…

End of content

No more pages to load