During the early 1970s, amid a backdrop of political tension and cultural shifts, an unexpected chapter in intelligence history unfolded: the CIA embarked on an ambitious and curious experiment to investigate psychic phenomena. This venture, sparked in part by swirling rumors about Soviet psychotronic research, led to the establishment of the Stargate Project—a secret program dedicated to exploring the potential military applications of psychic abilities.

At its core, the Stargate Project sought to determine whether individuals could perceive information hidden from ordinary senses, using what we now refer to as "remote viewing." The foundational experiment took place in 1972 at the Stanford Research Institute, where physicist Harold Puthoff and engineer Russell Targ, under CIA funding, designed a methodical approach to uncover psychic potential.

Their protocol was intriguing in its simplicity yet complex in execution: they would select a willing participant—anyone, theoretically—as their "maybe-psychic" subject. A set of twelve distinct geographic locations was compiled, unknown to the participant. While an experimenter and the participant stayed isolated in a room, another team member covertly traveled to one of these locations accompanied by observers, who strolled the area attempting to act as psychic "beacons." The participant was then asked to verbally describe and sketch what they "sensed" from the remote site despite no direct knowledge of the location.

This cycle repeated multiple times, and subsequently, a blind judge attempted to match each transcript—recorded conversations and sketches—with the actual locations. The results seemed astonishing: out of 45 attempts, judges matched 24 correctly, a feat statistically improbable by chance, resulting in a study published in the respected journal Nature. The implication was clear; psychic abilities might indeed be real, defying conventional scientific understanding.

However, the story did not end there. Years later, skeptics like David F. Marks and Richard Kammann undertook a painstaking effort to replicate the experiments exactly. The outcome was strikingly different. No judge in their recreations could reliably match transcripts to locations above chance. The unraveling of these discrepancies revealed a critical flaw—the original transcripts contained subtle, unintended clues.

For example, phrases like “I’ve been trying to picture it… where you went yesterday on the nature walk” offered temporal anchors, informing judges about the order and context of the sessions. Moreover, the order in which locations were presented to judges corresponded to their chronological visitation, allowing logical deduction rather than psychic insight to guide matching. Other indicators, such as observer names, times of day, or increasing confidence in the participants’ descriptions, inadvertently served as cognitive breadcrumbs.

Further tests demonstrated that individuals, including Marks himself, could perfectly match transcripts to locations without ever seeing the sites, solely by analyzing these unintentional cues. This revelation exposed the importance of rigorous experimental design and the perils of subconscious information leakage—a lesson indispensable to empirical science.

One of the enduring curiosities arising from both original and replication studies was that participants consistently believed in the authenticity of their psychic experiences, even when objective evidence proved otherwise. This phenomenon touches on fascinating psychological dynamics about perception, belief, and self-deception that continue to intrigue researchers today.

While the Stargate Project ultimately yielded no practical intelligence advantage and was quietly shuttered, its legacy lingers as a captivating exploration at the boundaries between science, belief, and the unknown. It underscores how the search for extraordinary capabilities can reveal as much about human cognition and experimental rigor as about paranormal potential.

In summary, the CIA’s flirtation with psychic research serves both as a historical anecdote about Cold War-era ambitions and as a cautionary tale emphasizing the necessity of critical scrutiny in all scientific endeavors, especially those venturing into the shadows of extraordinary claims.

News

An Unexplained Mystery in the Skies: A Chilling True UFO Experience Above Her Home

On a quiet night the street stayed still, and Sandra sat outside her modest Pennsylvania home. The neighborhood rested as…

Exploring the Shadows: Delving into the Lunar Landing Conspiracy Theories

In the vast cosmic theater, where celestial bodies dance in the endless expanse of space, the moon landing stands as…

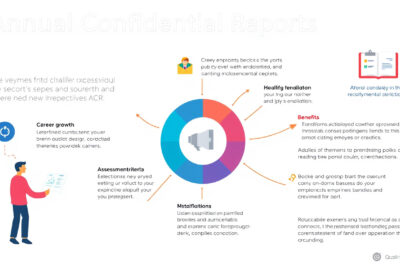

Understanding Annual Confidential Reports (ACR): Insights into the Essential Assessment Tool for Career Growth

Annual Confidential Reports (ACRs) play a pivotal role in the career trajectory of civil servants across various government sectors, whether…

Unlocking the Unknown: Tom Campbell’s Insights on the Mysterious Disappearance of Flight 370 Through Remote Viewing

The disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014 remains one of the most baffling aviation mysteries in modern history….

Exploring America’s Secrets: 30 Fascinating Underground Cities You Never Knew Existed

America is home to a remarkable network of underground cities and hidden complexes that many people have never heard of….

Unraveling the Enigma: The Curious Case of Epstein’s Jail Video and Trump’s Surprising Moment of Silence

The tangled narrative surrounding Jeffrey Epstein’s case continues to bewilder the public, especially after the latest revelations about the handling…

End of content

No more pages to load