Deep within the rugged terrain of Colorado Springs lies a marvel of Cold War military engineering: the Cheyenne Mountain Complex. Widely regarded as one of the most secure and critical facilities in the world, this underground fortress has played a crucial role in North American defense for decades. Far more than just a bunker, it is a bustling underground city built to withstand the unimaginable, safeguarding vital military operations and sensitive government functions through eras of evolving threats.

A Fortress Carved from Granite

Constructed between 1961 and 1966 at a staggering cost equivalent to $1.5 billion today, the Cheyenne Mountain Complex was designed to endure a 30-megaton nuclear blast detonated as close as 1.2 miles away. To achieve this, more than 693,000 tons of solid granite were painstakingly excavated to house a network of over a dozen multi-story buildings beneath the mountain’s massive surface.

Each of these buildings rests atop 1,300 metal springs—massive half-ton shock absorbers engineered to protect sensitive equipment from earthquakes or nuclear detonations. Remarkably, the suspension system is so finely tuned that when the original heavy computers were removed in a modernization effort, the buildings became lighter and shifted out of alignment, forcing technicians to re-tension the springs.

Life Inside the Mountain

Though devoid of windows, the mountain’s interior is essentially a self-contained city. Facilities include a medical center, dentist’s office, cafeteria, convenience store, chapel, and a 24/7 gym. To sustain uninterrupted operation, the complex houses an enormous supply infrastructure: six generators producing over 10 megawatts of power, fueled by 500,000 gallons of diesel stored in rock-carved reservoirs, along with millions of gallons of water reserved for drinking and heat management.

Interestingly, the internal activity generates so much heat that approximately 40% of the facility’s power is dedicated to air conditioning systems. This attention to maintaining a stable and habitable environment is critical given the mountain’s intended role as a last bastion of military command under extreme conditions.

NORAD and the Cold War Legacy

The mountain’s original mission was as the headquarters for the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), a joint U.S.-Canadian initiative established in 1958 to monitor skies against Soviet bombers, missiles, and space threats. The vast array of sensors—radars, satellites, and early-warning systems—fed critical data into the complex, enabling rapid detection of airborne objects. Within its first week alone, NORAD tracked over 100,000 airborne objects, dispatching fighter jets to investigate any unidentified contacts.

The facility’s iconic 25-ton blast doors, each perfectly balanced to the point of bouncing, were designed to seal off entrances in under a minute, protecting occupants from nuclear blasts. Although no direct nuclear attack ever occurred, NORAD remained vigilant through decades of Cold War tensions, intercepting Soviet bombers and preparing for retaliation in case of hostilities.

Modern Role and Adaptation

By 2006, advances in missile accuracy and nuclear warhead power had rendered the mountain susceptible to destruction by modern weapons. Consequently, NORAD relocated to a less fortified nearby building at Peterson Air Force Base, and Cheyenne Mountain was placed in a “warm shutdown.” However, the mountain was revitalized in 2011 and repurposed as the Cheyenne Mountain Space Force Station, housing multiple government agencies tasked with monitoring space and cyber threats.

Today, while NORAD occupies less than a third of the complex’s space, the facility remains fully operational and staffed by around 400 personnel during weekdays. It also serves a vital role as the only Department of Defense-certified underground facility protected against high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (EMP) attacks—preserving critical electronics from severe disruption.

Moreover, the mountain functions as a secure command center designed for worst-case scenarios including natural disasters, cyberattacks, biological and chemical threats, civil unrest, and limited or large-scale nuclear events. This elevates Cheyenne Mountain beyond its Cold War origins into a modern, multi-threat resilient fortress.

Other Noteworthy Complexes and the Future

Cheyenne Mountain is not unique: a Canadian counterpart, known as “The Hole” near North Bay, Ontario, was similarly built for nuclear defense during the Cold War. With its own underground command center, resilient to a 4-megaton blast, it was ultimately decommissioned and moved above ground in 2006 due to strategic shifts.

Ambitious concepts for even deeper and more resilient command centers, capable of surviving multiple 300-megaton nuclear strikes and located thousands of feet underground, were once considered by North American governments, but no public evidence suggests these were ever constructed.

The Enigma Inside: What Really Happens?

Despite some public information, the true nature of activities inside Cheyenne Mountain remains heavily classified. Employees analyze massive streams of data from around the globe, identifying risks and providing vital intelligence to decision-makers—right up to the President. The facility is a hub of cyber defense and space monitoring, yet the exact daily workings are shrouded in secrecy, with publicly released visuals often showcasing staged or simulated data.

Conclusion

Cheyenne Mountain Complex stands as a testament to Cold War ingenuity and the enduring need for secure defense infrastructure in an uncertain world. As technologies evolve and threats diversify, this vast underground city remains a keystone of North American defense readiness, blending historic resilience with modern capabilities. Through its unparalleled fortification, strategic significance, and technological sophistication, Cheyenne Mountain remains the pinnacle of security—a fortress where even in the most dire of circumstances, critical operations will continue, deep inside the mountain’s rocky heart.

News

Decoding the Moon’s Mysteries: Current Events and Cosmic Changes

The Moon, Earth’s closest celestial neighbor, has long captured human imagination. From ancient poets to modern scientists, its serene glow…

Unveiling the Shadows: What Secrets Does MI6 Keep Under Wraps? | Explorers Digest

The British Secret Intelligence Service, widely known by its codename MI6, has long captured public imagination with images of daring…

The Untold Story: How the CIA’s Covert Operations Gave Rise to a Cocaine Empire

In December 1989, the United States launched its largest military operation since the Vietnam War, invading Panama with over 25,000…

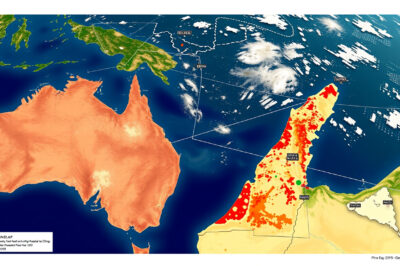

Unveiling Pine Gap: Its Strategic Influence in the Gaza Conflict

Australia is often perceived as a distant, peaceful country, far removed from the complex web of international conflicts and wars….

Uncovering Resilience in Absence: A Journey with Steven Furtick

Life often demands that we move forward before we feel prepared, stepping into unknown terrain with little to no clear…

Unraveling the Mystery of Ion Engines: The Pinnacle of Efficient Space Propulsion

When we think about space travel, rockets blasting off with fiery explosions come to mind. Chemical rockets, which rely on…

End of content

No more pages to load