🌕🚀 China’s Moon Haul: The Discovery That Could Rewrite Earth’s Energy Future ⚡🪐

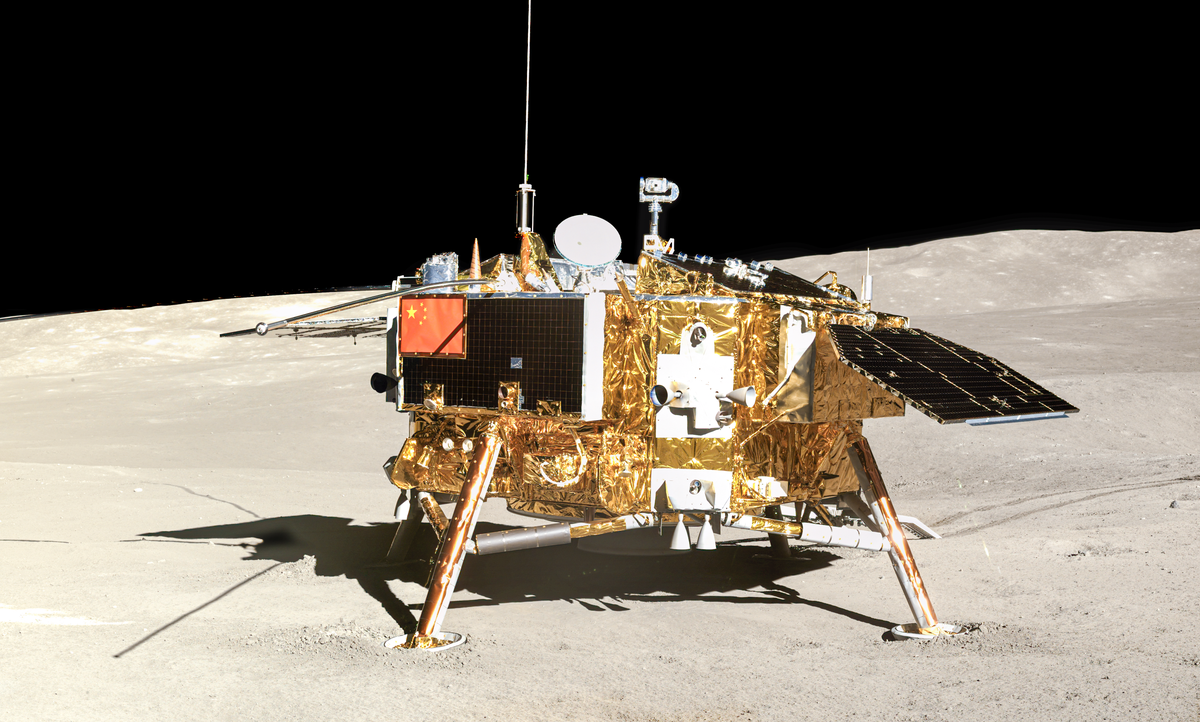

The Chang’e-5 mission was a technological ballet on an interplanetary stage.

At nearly eight tons, the spacecraft was built not just to land, but to dig — reaching deeper into the Moon’s skin than anyone had in decades.

Its target, Oceanus Procellarum, was no random plain.

This basaltic sea of ancient lava, watched over by the 5,250-foot Mons Rümker formation, has long whispered secrets to scientists peering through orbital cameras.

They suspected this site held rocks a billion years older than Apollo’s samples — rocks from a time when the Moon’s surface seethed with volcanic fury.

On December 1st, 2020, China’s heavy-lift Long March 5 roared into the sky, carrying Chang’e-5 beyond Earth’s grasp.

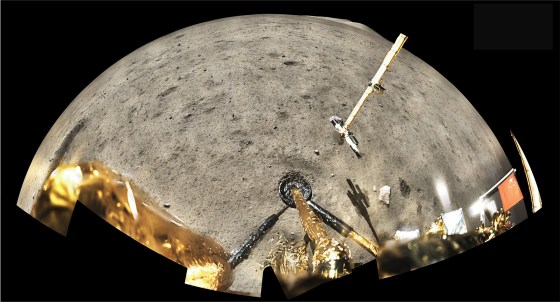

Twenty-three days later, the lander settled into Procellarum’s powdery stillness.

The clock was ticking — just 14 Earth days before the lunar night would plunge the site into deadly cold.

The lander went to work, deploying drills capable of cutting through layers untouched by sunlight for eons.

Unlike Apollo’s shallow scoops, these cores reached strata locked since before mammals walked the Earth.

Within the samples lay glassy beads — microscopic spheres forged in the crucible of meteor impacts — and they would turn out to hold the mission’s most astonishing revelation.

When the ascent vehicle blasted back into orbit, rendezvoused with its waiting module, and began the long trip home, few could guess what was inside those hermetically sealed

canisters.

On December 17th, 2020, the return capsule parachuted into Mongolia.

Inside: 3.8 pounds of ancient Moon.

Under the microscopes back on Earth, scientists found something that shattered decades of certainty: water — hidden in those tiny glass beads, scattered across the lunar surface.

Each bead was minuscule, each droplet microscopic, but their sheer abundance was staggering.

Estimates suggest a metric ton of lunar soil could yield up to 2,000 liters of water under Earth-like heating conditions.

That means future astronauts won’t be chained to the Moon’s polar ice — they could land almost anywhere, bake the regolith, and harvest their own water supply for drinking,

farming, and even fuel production.

But the beads were just the beginning.

Embedded in the deeper cores was something the world had never seen before: a new phosphate mineral, christened Changesite-(Y) after the mission and the Moon goddess of

Chinese myth.

This wasn’t just a curiosity for the mineralogists’ cabinet — its crystal structure hinted at a capacity to store helium-3, the elusive isotope long dreamed of as the perfect nuclear fusion

fuel.

Fusion is the holy grail of clean energy — no greenhouse gases, almost no radioactive waste, and the potential to power civilizations for millennia.

On Earth, helium-3 is almost impossibly rare.

On the Moon, Chang’e-5’s findings suggest, it may be waiting in industrial quantities.

Some scientists calculate that just 27.

6 tons could meet the United States’ annual energy needs.

Suddenly, the Moon wasn’t just a romantic destination; it was an energy goldmine.

The implications are seismic.

Helium-3 could drive a new space race — not for flags and footprints, but for mining rights, processing plants, and orbital infrastructure.

Nations and private companies are already sketching plans for lunar bases that double as industrial hubs.

Water from the glass beads could sustain crews and grow food, while minerals like Changesite-(Y) feed reactors that power Earth.

Chang’e-5’s landing site choice now looks almost prophetic.

Mons Rümker’s volcanic history means its rocks are chemically diverse — a geologist’s treasure chest and, possibly, an engineer’s jackpot.

The cores pulled from beneath Procellarum carry chemical fingerprints of billion-year-old eruptions, impact events, and the slow, relentless bombardment of solar wind.

Together, they tell a story of a Moon far more dynamic than the “dead rock” label it’s worn for decades.

For China, the mission was more than a scientific coup; it was a declaration of capability.

The precision landing, autonomous drilling, on-site sample sealing, and in-orbit rendezvous marked it as one of the most technically sophisticated missions ever attempted.

It’s no accident that Chang’e-6, already in planning, will target the Moon’s far side — a place even more geologically mysterious.

For the rest of the world, the samples are an invitation and a warning.

Chang’e-5’s team has pledged to share materials with international scientists, but the find has also sharpened geopolitical focus on lunar resources.

Who will own the right to mine helium-3? What environmental protections, if any, will be enforced? How do we balance scientific discovery with industrial exploitation on a body that

belongs to no one?

The answers will shape not just the next decade of space exploration, but perhaps the next century of human energy policy.

If Changesite-(Y) proves viable as a fusion catalyst, the stakes are nothing less than the end of the fossil fuel era.

Yet in the quiet of China’s lunar labs, amid the hum of vacuum chambers and spectrometers, there’s a more immediate thrill — the thrill of cracking open a rock that hasn’t seen

sunlight in over a billion years, and realizing it may hold the blueprint for humanity’s survival.

Chang’e-5 reminded us of something profound: the Moon still has secrets, and some of them may be the keys to our future.

The next time a rocket rises from Hainan toward that pale disc in the night sky, it won’t just be chasing history.

It’ll be chasing destiny.

News

“From Best Friends to Silent Enemies”: The Day Snoop Dogg Turned His Back on 2Pac — and Never Looked Back

🐍 “From Best Friends to Silent Enemies”: The Day Snoop Dogg Turned His Back on 2Pac — and Never Looked…

“The Easy Thing”: Eazy-E, Suge Knight, and the Chilling Rumor That Still Haunts Hip-Hop

💉 “The Easy Thing”: Eazy-E, Suge Knight, and the Chilling Rumor That Still Haunts Hip-Hop 😱🔫 By 1990, Eazy-E was…

“He Wouldn’t Leave His Room”: The Night Jay-Z Hid from Tupac… and the Secret War That Changed Hip-Hop Forever

🚨 “He Wouldn’t Leave His Room”: The Night Jay-Z Hid from Tupac… and the Secret War That Changed Hip-Hop Forever…

“You Got Me”: The Moment Nipsey Hustle Fell… and the Secret Tape That Could Take Down Big U Forever

💣 “You Got Me”: The Moment Nipsey Hustle Fell… and the Secret Tape That Could Take Down Big U Forever…

From Nipsey’s Legacy to West Coast War: The Viral Black Sam vs. Snoop Dogg Footage That’s Splitting Hip-Hop in Two

🔥👑 From Nipsey’s Legacy to West Coast War: The Viral Black Sam vs. Snoop Dogg Footage That’s Splitting Hip-Hop in…

Tupac’s Quad Studios Ambush: The Night the Trap Was Set and the Betrayal Began

🔫🎤 Tupac’s Quad Studios Ambush: The Night the Trap Was Set and the Betrayal Began 🩸💔 In late 1994, Tupac…

End of content

No more pages to load