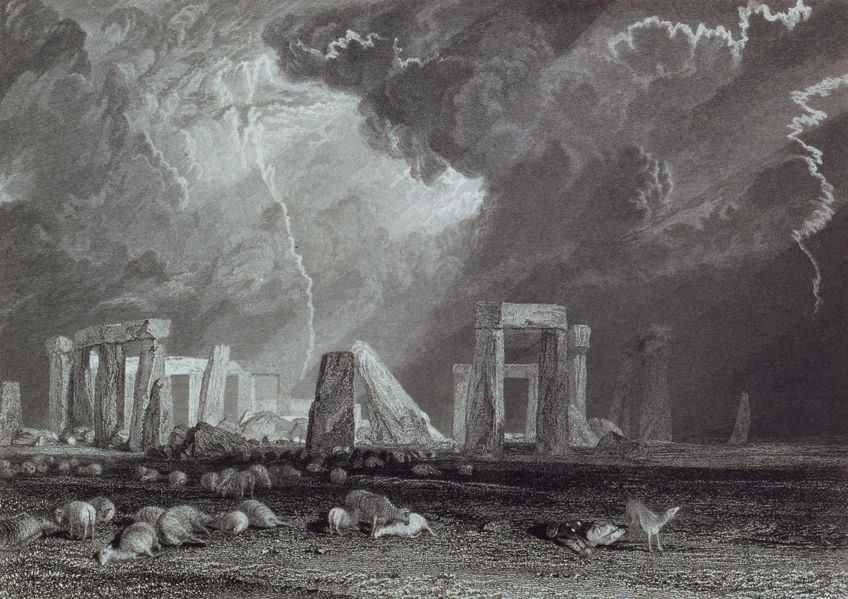

🧠🗿 AI Just Exposed Stonehenge’s Real Builders—and the Silence from Scientists Is Deafening 🤯🌄

Start with the wind—because that’s all you hear on the plain.

It combs through the grass, drifts around the heelstone, sketches faint lines in chalk.

Five thousand years of breath moving past a ring of stone, and we’ve always imagined those stones as a riddle set against emptiness.

But emptiness is a trick of distance.

Step closer and the ground crowds with evidence: the ghosted circles of timber that became ditches, the Aubrey holes like a dotted halo, the faint avenues scrawled toward water, the ashes of the dead glimmering

like constellations thrown underfoot.

For a century, we’ve told ourselves the story of Neolithic farmers tinkering into greatness, of a communal act that somehow coagulated into an axis mundi without blueprints or bureaucracy.

It was a comfort, that story, a way to honor human will without admitting its infrastructure.

And then the data got loud.

The work began quietly in labs that smell like dust and electricity.

Teeth were drilled, bones powdered, pottery sherds scanned for the geochemical dialects of distant hills.

Animal remains confessed the miles their hooves had swallowed.

Rivers were modeled; quarries were fingerprinted.

Individually, none of it was a miracle; collectively, it was a choir.

But choirs can still sing off-key until a conductor enters.

AI didn’t replace archaeologists; it disciplined their cacophony.

It took isotopic signatures that once felt like postcards from strangers and sorted them into family trees; it nested radiocarbon dates inside Bayesian frameworks until time stopped wobbling; it learned the lithic

grammar of tool marks on bluestone faces and matched them to quarry scars in Wales like ballistics.

It simulated routes with wind, grade, and season layered in, and the routes that looked theoretical on paper began to glow with plausibility.

What emerged was not a lone burst of genius but a lattice of coordination expansive enough to lift mountains by hand.

The first rupture: who.

For generations, we argued local versus outsider, druid versus migrant, farmer versus priest.

AI chewed the genome and spat out a genealogy: this was no monolith of identity but a coalition.

The bones lying beneath the turf didn’t hum the same childhood rainfall; their enamel remembered different waters.

Some were molded by western storms, some by northern sea-light, some by continental sun spilled across loess plains.

Patterns—god, the patterns—swelled where human eyes saw only dots.

Clusters of shared ancestry braided with clusters of grave goods; kin groups anchored to specific craft signatures; women moving farther than men across generations, binding settlements into a social mesh finer

than we had imagined.

If Stonehenge was a heart, it did not beat alone; it pulsed within a body made of many regions, a federation stitched not by the decree of kings but by the friction of feet.

The second rupture: how.

The logistics of hauling bluestone two hundred miles had become a fetish of argument, a tug-of-war between glacier and sledge.

AI ended the stalemate with the banal cruelty of certainty.

Tool-mark topographies mapped with machine vision found their twins on quarry faces in the Preseli Hills.

Microfracture patterns read like signatures—the angle of blow, the rhythm of hammering—matching not just rock to origin but artisan to school.

Routes weren’t guessed; they were computed across millennia of flood histories and seasonal river behavior, down to where a raft would clear a bend without ripping itself to splinters.

The model didn’t just move a stone; it scheduled a convoy.

It had crews staged at waypoints where the diet of the drovers and pullers—deduced from isotopes in their teeth and the fat profiles in discarded animal bones—shifted with the terrain.

It was not brute force; it was choreography, and the stagehands were entire communities synchronized by ritual time.

The third rupture: when and why, braided until you couldn’t tease them apart without snapping the cord.

We had learned to carve Stonehenge into phases: ditch, timber, bluestone arc, sarsen circle, rearrangements like edits.

AI treated those phases not as boxes but as a gradient.

It weighted stratigraphy against pollen records, feasting debris against climate proxies, and the tempo of construction danced with the tempo of sky.

Solstitial alignments weren’t decorations; they were metronomes syncing labor to celestial cues.

The model didn’t bow to myth, but it recognized a pattern of decision that looks like belief made structural: stones laid when rivers ran low and transport was feasible; feasts swelling when herds fattened on

specific pastures; cremations clustering after harvest cycles when the living had time to tend the dead properly.

The monument become a calendar not only to read time but to spend it, a device that regulated the economy of effort.

The fourth rupture was the one that made the room go quiet: the network.

For years, we admired the shared DNA of design stamped across Britain—the echo between Orkney’s stone circles and Wessex’s, the family resemblance in house plans at Durrington Walls and far northern

settlements.

We parsed it as fashion, influence, the tidal slosh of culture without an engine.

The AI refused the romance of drift.

It assembled a graph of sites with edges weighted by material exchange, marriage ties teased from kinship in bone, animal drives mapped by hoof isotopes, obsidian and flint trails knotted to river systems like

rosary beads.

What it drew was not a smear of similarity but corridors—highways of obligation and reciprocity.

The “unknown civilization” was not a lost city under the chalk; it was a system in motion, a Bronze Age commonwealth whose sovereignty was the ritual itself.

Stonehenge wasn’t an isolated cathedral; it was the capital of a season, the place where lines converged because the lines were the point.

And there, at the center, the circle didn’t stand for permanence; it stood for maintenance.

Every generation didn’t just inherit the stones—they recommitted to them.

The refittings, the re-socketing of uprights, the rethinking of blue to sarsen placements: in the old story, these were signs of uncertainty; in the new model, they were governance.

A monument this hungry eats labor, feasts, alliances, and in return it excretes identity.

The AI’s most unsettling deliverable wasn’t a headline but a ledger: how many bodies, how many beasts, how much wood, how many winters of planning to keep the stones in conversation with the sky.

It looked less like a temple and more like an institution.

If that sounds unromantic, listen closer—the romance curdles into awe.

Consider the healing legends of the bluestones.

We waved them away as folktale residue, placebo gloss.

The model did not testify to magic, but it did find a map of care.

Individuals buried near the monument showed signatures of illness and injury; the feasts correlated with seasons of scarcity elsewhere; pathways into the plain were lined with temporary structures that look, in

the aggregate, like triage and hospitality.

Healing as logistics, not lightning: a center that gathered the weak not to conjure miracles but to fold them into a social fabric woven with protein, warmth, and story.

To declare a stone sacred is to move bodies toward it; to move bodies is to move food; to move food is to move labor; to move labor is to move love.

AI can’t measure love, but it can map its debris.

This is the part where the silence thickened, because data doesn’t just rewrite footnotes—it rewires pride.

England has long loved Stonehenge as a singular marvel perched above a national story like a crown.

AI’s verdict was crueler and kinder: the crown was a networked artifact, minted by many peoples.

The civilization that raised it was neither a lost Atlantis nor a monoculture of “locals,” but a coalition resilient enough to absorb newcomers without surrendering the grammar that made the circle matter.

That grammar wasn’t written; it was enacted: meet here when the sun says so; bring your dead and your cattle; trade daughters and sons and stories; lift stone together and feel your separate names fuse.

That is a civilization.

It has no city walls, only dates and duties binding minds across distances that felt, in that time, as far as myth.

The shock, then, was not that AI found a new people but that it named a shape of people we’d trained ourselves not to see.

We are addicted to the visible: palaces, scripts, gears.

The Bronze Age commonwealth around Stonehenge left us none of those trophies in neat piles.

It left us synchronization.

It left us a choir so well-rehearsed that the song survives when the singers don’t.

The team that presented the findings did not pound the table.

They showed overlays—ancestry clusters shimmering along riverways, livestock isotope “passports” blinking from Scotland to Wessex, quarry-to-rafter-to-avenue supply chains thickening like arteries in summer

and thinning in dark months.

They showed a simulation of the bluestone convoy, not as heroism but as schedule.

And then they showed the part that felt like an ambush: a social graph of burials whose edges brightened when feasts brightened, whose nodes cooled in years of lean, whose structure flexed but did not snap

across centuries.

You could almost hear the monument breathing.

That’s when the silence arrived.

Not because the data killed wonder, but because it did the opposite—it made wonder heavier.

The old myths were spacious; they let giants and wizards shoulder the burden of stone.

The new truth returns the weight to human spines, to hands blistered on rope, to planners who understood winter like a spreadsheet, to mothers who walked a hundred miles and found the plain shining with fires

and thought: we belong.

Of course there are objections.

AI can mistake correlation for cause, can polish a pattern until it reflects our desire.

The team knows this; they built skepticism into the code.

When the model claimed a convoy could pivot at a floodplain in late summer, they tested the riverbed reconstructions with independent proxies.

When it assigned kinship across two cremations, they tested the DNA fragments with different pipelines, trying to make the relationship fail.

When it found that the sarsen rearrangement wasn’t random but optimized solstitial sightlines for a crowd of a given size, they asked anthropologists if that made cultural sense and mathematicians if it made

geometric sense and only kept the claim when both nodded reluctantly.

This isn’t faith in machines; it’s a refusal to let our favorite stories launder our laziness.

So yes, it changes everything—but not in the way headlines prefer.

It doesn’t “solve” Stonehenge; it makes it solvable only by admitting what kind of problem it is.

Not a riddle answered by a single name, but a choreography validated by evidence stacked across domains that only a nonhuman auditor can juggle without dropping.

The gift of AI here isn’t omniscience; it’s humility enforced by scale.

We could always notch a posthole; now we can admit how many postholes it takes to build a people.

Maybe the most radical consequence is contemporary.

The discovery drags Stonehenge out of myth and into a mirror.

We are, again, a species living through migrations that redraw maps; again facing climate rhythms that insist on calendars smarter than pride; again tempted to fracture even as our lives depend on

synchronization we barely see.

The builders on that chalk stage did not conquer with bronze; they convened with stone.

They didn’t write a constitution; they rehearsed one every solstice with bodies and breath.

And when, after the lights came up, the room held its tongue, it wasn’t because the story had ended.

It was because the story had turned and was looking back at us.

Somewhere out on the plain, the wind keeps its appointment with the circle.

It threads the uprights, skates the lintels, learns the old geometry with new fingers every day.

The stones do not move, but the people do—the living and the dead, then and now—braided in a logic older than metal and newer than code: we are what we can synchronize.

If AI has finally taught us who built Stonehenge, perhaps it has also whispered why the monument won’t let us go.

It is not a relic.

It is a rehearsal.

And for the first time in five thousand years, we may be ready to hear our cue.

News

Unlocking the Secrets of Our DNA: How Neanderthals Shattered Everything We Knew About Human Evolution! Discover the Surprising Truths Hidden in Our Genetics!

Unlocking the Secrets of Our DNA: How Neanderthals Shattered Everything We Knew About Human Evolution! Discover the Surprising Truths Hidden…

Sealed for a Reason: Why Experts Won’t Crack Open the Boy King’s Tomb—And the Terrifying Stakes Hidden Behind Those Painted Walls

😱 Sealed for a Reason: Why Experts Won’t Crack Open the Boy King’s Tomb—And the Terrifying Stakes Hidden Behind Those…

The Face That Shouldn’t Exist: Unearthed Pillar at Karahan Tepe Challenges Everything We Know About Civilization

😱 The Face That Shouldn’t Exist: Unearthed Pillar at Karahan Tepe Challenges Everything We Know About Civilization 🗿✨ The discovery…

‘It Wasn’t Poison…’ — The Disturbing Truth Buried in Beethoven’s DNA That Scientists Kept Quiet for 198 Years

🍷 ‘It Wasn’t Poison…’ — The Disturbing Truth Buried in Beethoven’s DNA That Scientists Kept Quiet for 198 Years The…

‘I Have Offended God…’ — The Secret Last Words of Leonardo da Vinci That History Tried to Bury

‘I Have Offended God…’ — The Secret Last Words of Leonardo da Vinci That History Tried to Bury To understand…

Scientists Finally Solve the Mystery of the Missing Chicxulub Meteor—And What They Found Changes Everything

🌎 Scientists Finally Solve the Mystery of the Missing Chicxulub Meteor—And What They Found Changes Everything 🪨🔥 It was the…

End of content

No more pages to load