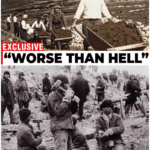

🔥“Built on Bones & Betrayal!”: 20 Insane Gulag Secrets Stalin NEVER Wanted You to Know 💀🔒

It begins, as all nightmares do, with a lie.

Stalin’s Gulag system—officially known as GULAG, short for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei (Main Administration of Camps)—was sold as a way to rehabilitate “enemies of the people” through labor.

But beneath this bureaucratic euphemism lay an empire of death, stretching across the icy veins of Siberia, where human life was ground down to statistics, and every minute not spent working was a minute closer

to vanishing.

Take the White Sea–Baltic Canal, for example.

While the Suez took over a decade, Stalin ordered this 140-mile waterway completed in less than two years—using only picks, shovels, and prisoners’ hands.

No machines.

No safety.

Just bodies, bones, and blood.

Some 280,000 inmates were dragged into the project.

Between 12,000 and 25,000 never came out.

The canal they built was too shallow, too slow, and too pointless to matter—but Stalin didn’t care.

He wanted a monument, and he got one—just not of stone, but of skeletons.

If that wasn’t gruesome enough, there’s Nazino Island, also known as Cannibal Island.

May 1933: Over 6,000 prisoners—many arrested for petty crimes or no crime at all—were dumped on this speck of land in Siberia with no tools, no shelter, and sacks of flour…

but no way to cook it.

Within days, people were dying.

Within weeks, they were eating each other.

Flesh was sliced from corpses.

Guards shot escapees.

By summer, more than 4,000 were gone.

Nazino wasn’t a settlement—it was a death lab in social collapse, one the Soviets kept buried for decades.

Then there’s the infamous Kolyma Highway—the Road of Bones.

A 1,200-mile stretch of permafrost, constructed with such disregard for human life that the dead were literally buried beneath the road.

Workers froze to death, starved, or collapsed from exhaustion, only to be covered in gravel and driven over.

To drive it today is to ride over a graveyard so vast it defies mourning.

Not every prisoner was sent to dig, however.

Some ended up in Sharashkas—secret scientific prisons where engineers, physicists, and intellectuals were forced to work on Soviet weapons and surveillance tools.

One such prisoner was Léon Theremin, inventor of the eerie electronic instrument that gave 1950s sci-fi its voice.

Inside the Gulag, he created “The Thing”—a passive listening device hidden inside a wooden gift to the U.S. ambassador.

It sat above his desk for seven years, silently transmitting conversations to KGB agents across the street.

No batteries.

No wires.

Just pure, terrifying genius—built under duress.

How bizarre was life in these camps? Jokes could kill you.

Literally.

A well-timed quip about Stalin might earn you 25 years of hard labor.

Up to 200,000 people were imprisoned simply for telling political jokes.

One bakery worker joked that he saved Stalin from drowning—and got ten years.

Laughter was not just discouraged—it was criminalized.

But the silence didn’t stop prisoners from finding ways to speak.

Through tooth powder scrawls on cell walls or tap codes passed through concrete, inmates forged a hidden language of resistance.

One prisoner, after months of tapping, realized a stranger had been asking him, “Who are you?” in knocks.

That question—haunting, human, defiant—echoed through the gulag like a whispered scream.

In the frozen hell of Vorkuta, over 2 million prisoners were cycled through its 130 camps.

With temperatures plummeting to -40°F, inmates were worked to death in coal mines.

Yet in 1953, they staged a revolt—one of the largest in Gulag history.

It was crushed, but not before it proved that even in the depths of horror, people will fight.

And that horror ran deeper still.

Serpentinka, a killing site disguised as a labor camp, masked executions with the roar of tractor engines.

Bodies were buried in mass graves and flushed into rivers during spring melts.

Butugychag, another camp, forced prisoners to mine uranium by hand—without protection.

Life expectancy? Less than one year.

The hills around it remain radioactive.

The tools, the barracks, the graves—all still there, ghosting through the fog like a warning we refuse to read.

Despite it all, in some camps, culture became rebellion.

Inmates held puppet shows.

Sang arias.

Staged Shakespeare.

Sometimes the guards watched.

Sometimes they crushed the shows under their boots.

But for prisoners, art was air.

A whispered line of poetry in a lice-ridden barracks became the difference between sanity and collapse.

Actress Valentina E.

recalled dancing barefoot in snow, while dissident poets turned each verse into a silent scream.

And what about punishment? You might imagine beatings, torture, forced labor.

But in some cases, it was worse.

In summer, the mosquitoes came.

Siberia’s wet heat unleashed black clouds of biting swarms.

As punishment, guards stripped prisoners naked, tied them near marshes, and let nature devour them.

Survivors described breathing in bugs.

Eyes swollen shut.

Entire bodies pulsating with bites.

One guard allegedly called it “God’s whip.”

Even food was an experiment in humiliation.

You might get soup served in a kerosene tin, or if you were lucky, a handmade spoon carved from a bone.

Those utensils became sacred—symbols of survival, carried through years of degradation.

Starvation forced some prisoners to smash their own limbs to escape labor.

Others injected dirty needles into their flesh, choosing infection over frostbite.

Still, many were thrown back into work—crippled, bleeding, starving.

Perhaps the cruelest twist lies in stories like Lovett Fort-Whiteman—an African-American communist who moved to the USSR believing in its dream of racial equality.

He became a darling of Soviet society, a symbol of solidarity.

But when Stalin’s purges hit, he was labeled a traitor, sent to the mines of Kolyma, and left to starve and die in the very country he championed.

The man once celebrated in Time magazine vanished—erased by the system he believed in.

And through it all, the world was kept in the dark.

Foreigners were banned from traveling near camps.

Satellite cities like Vorkuta, built entirely by forced labor, remained secret for decades.

Even today, some of these sites are unmarked, unrecognized, unmourned.

So what was the Gulag?

It was a machine.

One fueled by fear.

By ideology.

By silence.

It was a place where truth was illegal, laughter was lethal, and even death was recycled into labor.

A place so surreal, so brutal, and so meticulously engineered that it seems more like a dystopian novel than real history.

But it was real.

And its echoes still reverberate.

In abandoned barracks now overgrown with moss.

In sunken roads paved with bones.

In the unmarked graves of poets, musicians, scientists, jokers, and believers.

In every story buried beneath the snow.

We were told the Gulags were just prisons.

But what they really were…

was a calculated annihilation of the soul.

Now ask yourself: What other secrets still lie frozen in the soil of Siberia?

And why, even now, are we only hearing them whispered—never shouted?

Because some truths, it seems, are still too dangerous to say out loud.

News

“This Changes EVERYTHING!”: Hidden Megacity Unearthed Beneath Turkey Stuns Experts and Silences Graham Hancock

💥 “This Changes EVERYTHING!”: Hidden Megacity Unearthed Beneath Turkey Stuns Experts and Silences Graham Hancock 🧠🏛️ It was supposed to…

“Use Me As a Shield?” — The Night Suge Knight Grabbed Diddy to Survive a Hit

💥 “Use Me As a Shield?” — The Night Suge Knight Grabbed Diddy to Survive a Hit 🔫🔥 In the…

“Tell the World I’m the King” — The Secret Battle for New York Between Jay-Z and 50 Cent

💥 “Tell the World I’m the King” — The Secret Battle for New York Between Jay-Z and 50 Cent 🤐🗽…

“Tell Snoop I Wanna Talk…” — The 11-Hour Standoff That Brought Police, SWAT, and Hollywood to a Screeching Halt

💔 “Tell Snoop I Wanna Talk…” — The 11-Hour Standoff That Brought Police, SWAT, and Hollywood to a Screeching Halt…

“He Set 2Pac Up and Vanished” — Haitian Jack’s Chilling Rise and the Night That Changed Rap Forever

🔥 “He Set 2Pac Up and Vanished” — Haitian Jack’s Chilling Rise and the Night That Changed Rap Forever 😱💣…

“You’ll Never Be Taken Seriously” — Jay-Z’s SHOCKING Words to Ludacris That Left the Room Frozen

🚨 “You’ll Never Be Taken Seriously” — Jay-Z’s SHOCKING Words to Ludacris That Left the Room Frozen 😳 It happened…

End of content

No more pages to load