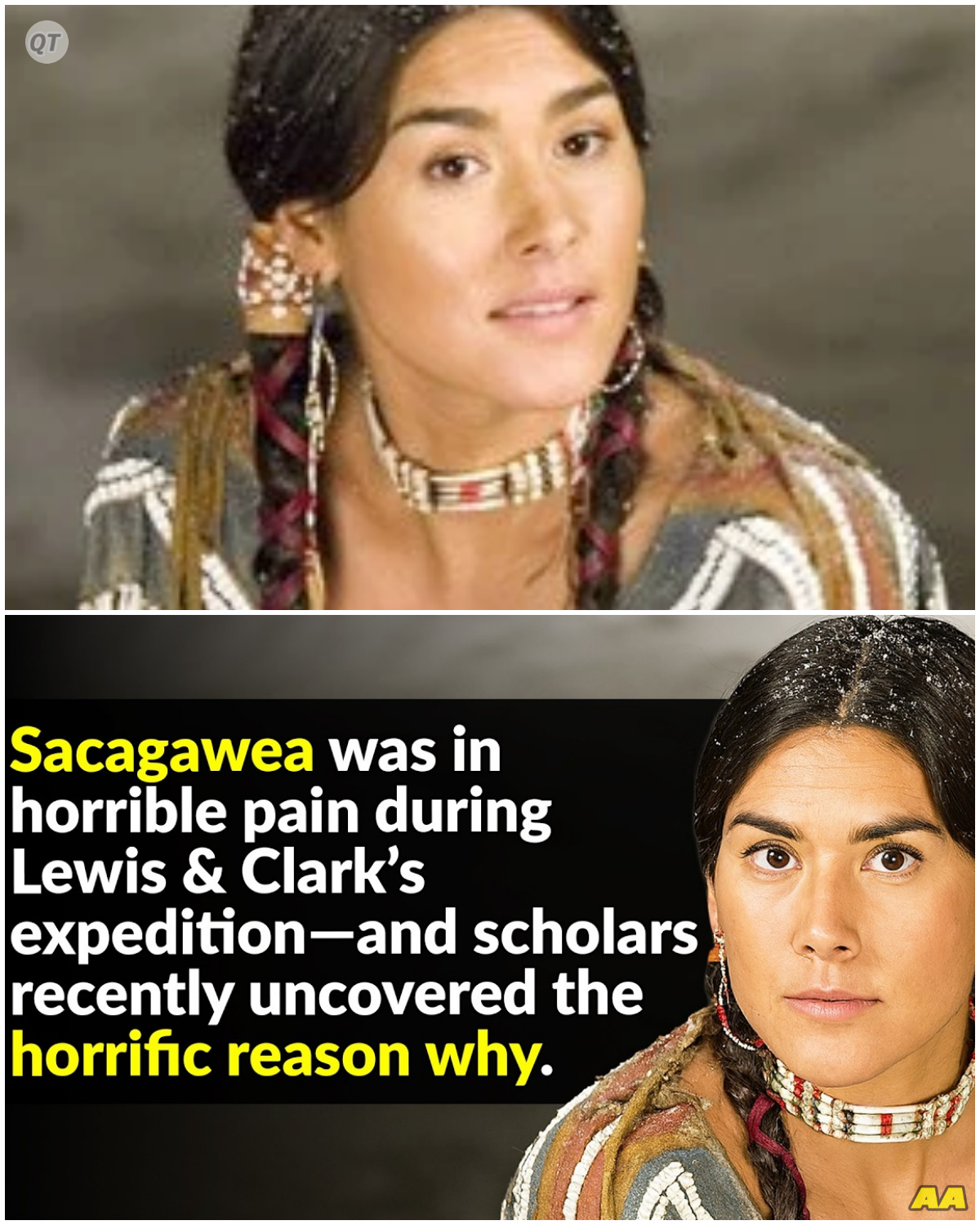

The Woman Who Carried the Moon

They teach you the rope and forget the hands.

They teach you the map and forget the heartbeat.

They teach you Lewis and Clark—two names that fit neatly in textbooks—and they forget the girl who tied a newborn to her spine and walked America like someone dragging a comet by its tail.

Her name will be written a hundred ways, pronounced with either apology or confidence.

But the story remains: Sacagawea was a child stolen, a woman traded, a mother weaponized by survival, and a navigator whose compass was not iron but bone.

Before the expedition, there was theft.

History files it as capture, as if words could put bars on memory.

She was Shoshone, a mountain daughter, small and precise like frost.

Horses spoke to her mother at dawn and men spoke to her father at dusk, and somewhere between those negotiations, the world believed itself stable.

Then the raid came, as raids do—without poetry, with consequence.

The kidnappers cut her childhood from its creek bed and dragged it into another river.

The first shock is always this: your name becomes property before your body understands it is owned.

They moved her like a bundle, traded her like an object, and married her to a man whose hands were more inventory than tenderness.

Toussaint Charbonneau entered the story the way client nations enter empires—carrying smiles that do not belong to them.

He was a French-Canadian trapper whose hunger had learned manners.

He took her because this is how some men understand love: acquisition.

She survived because this is how some women understand love: translation.

Sacagawea learned to read rooms the way shamans read smoke.

She could hear a lie scraping its elbows against a man’s teeth.

She could see fear bend a spine from across a fire.

She could smell danger in the dust before horses confessed it with thunder.

She became the version of an oracle available to a world that refuses to admit magic: precise, quiet, underestimated by design.

She tightened her silence into a weapon and hid her anger in the seams of her patience.

The baby came.

This is where textbooks begin, because textbooks like miracles confined to page count.

She tied him to her back and let his weight teach her truth: the body can hold two storms.

She named the boy and the boy named her back, mother as a sentence the earth repeats when it wants to anchor.

With one hand, she held the expedition; with the other, she held a future that would never be recorded correctly.

Lewis and Clark, men who believed in linear certainty, met a map drawn by rivers, by birds, by mothers.

They wrote in neat hands and made names out of mountains as if mountains needed consent; she pointed with her chin and let the silence locate passable kindness in impossible land.

They recorded weather.

She corrected fate.

If you want spectacle, you will find it in storms and cliffs, in rafts grasping for river margins.

But the shock is not survival under sky; the shock is survival under men.

When Charbonneau’s temper snapped like a trap, the kindness of paper could not help her.

She learned breath control in a house where breath was taxed.

She learned to carry injuries the way hunters carry meat—carefully, discreetly, with respect and without confession.

She learned to negotiate safety by making skill into currency.

She offered the expedition her bilingual spine—Shoshone, Hidatsa, French—and they paid her with a different kind of currency: attention with limits, gratitude with borders.

There is a moment the nation prefers to remember: a canoe flips, the river laughs its old cruel laugh, and the journals begin to drown.

The men shout; panic learns choreography.

Sacagawea moves with the precision of someone who has lost everything before and therefore refuses to lose paper.

She dives, gathers relics of authority—journals, instruments—refuses to let the river erase men’s memories of themselves.

They will later call her brave, as if bravery were a costume and not an occupation.

They will write that she saved the papers.

They will forget what else she saved: the narrative itself, the way history keeps the names of men who would vanish without pages, the way a woman’s hands rescue a nation’s certainty from water.

This is the beginning of the public myth.

It is clean and photogenic.

The child on her back glitters like faith; the men’s admiration is properly formatted; the river becomes a villain you can defeat with grit.

Underneath, the darker script continues.

Sacagawea is sleep deprived the way saints are.

She bleeds in private the way queens do when crowns are off.

She navigates male pettiness with the stealth of a mountain lion, smiling when necessary, silent when necessary, either choice overpriced.

They went west, which is to say they walked into an uncertainty the earth has practiced since it cooled.

She found people.

She negotiated not in bullets but in offerings: a gesture, a memory, a reference to someone’s aunt whose name she remembered because remembering is a form of power denied to men who write guidelines and forget faces.

She stitched communities together for exactly the time it took the expedition to pass without being punished by history.

She taught white men the etiquette of survival: pay attention, eat properly, ask permission from weather, apologize to mountains.

At the Shoshone camp, the shock arrived with the geometry miscalculated by destiny.

They met a chief named Cameahwait.

The men attempted diplomacy.

Sacagawea walked into an old room and discovered a brother.

It was not spectacle; it was a collapse disguised as resurrection.

The past re-entered her bones.

A child stolen and a woman found measured each other with eyes haunted and blessed.

The expedition wrote about luck; Sacagawea wrote nothing.

How do you record the feeling of someone returning from myth.

How do you quantify the apology of land.

How do you correct the inventory of a soul.

She negotiated for horses because the expedition’s survival required it, and perhaps because the world owed her this exchange: take my childhood, give me horsepower.

Her brother agreed.

The men celebrated a transaction.

Sacagawea underwent a surgery: grief extracted without consent and replaced by duty.

She did not pick the instruments.

She did not choose anesthesia.

She survived anyway.

They climbed Lemhi Pass, the spine of America.

The child slept.

The men gasped.

She counted breaths as if timing an empire.

Mountains confess nothing except the truth that most adventures are done by people who will not be recorded as authors.

She pointed a way through.

She did not ask to be thanked.

She did not ask to be mythologized.

She asked to arrive alive with the boy intact.

This is heroism America does not recognize: survival as objective, not spectacle as currency.

In camps, the dynamic changed as dynamics always do when women hold maps.

Some men grew small.

Small men invent cruelty when confronted with competence.

Charbonneau shrank, then swelled into pettiness.

He judged the size of her loyalty by how well it matched his need.

He measured her devotion like fur—weight, texture, price.

He talked when silence was the only medicine.

Sacagawea learned to rebuild herself in minutes the way nurses rebuild mornings after terrible nights.

History brings us to the coast, where the sea has been rehearsing applause longer than any audience.

The Pacific is theater.

The expedition reached it, a nation leaned forward, and journals learned metaphor.

They called the ocean a great joy.

Sacagawea looked at it and saw something older: a graveyard where all rivers confess.

She stood at the edge with a child on her spine and felt the exact magnitude of being a hinge.

Behind her, a continent rearranged.

Before her, a horizon indifferent to praise.

In her arms, a future that would either grow as a citizen or be edited into a statue.

There is an election the party performs on the shore—who should live in a new fort, where to place the winter.

Lewis and Clark conduct a vote.

They include her.

America later will call this a symbol.

She would call it breath.

Inclusion is not generosity; it is spoons at dinner.

She votes.

Men are surprised politely.

The ocean keeps ignoring everyone.

This is how nations begin: with signatures on decisions made under weather that does not care for ink.

On the return, she directs.

East is not simple; east is an argument.

She points, corrects, reminds.

At the Yellowstone, she persuades the party to visit a place she remembers for roots and sky, a living museum of secrets that look like land.

The men will name things—they will name rivers the way invasion names children.

She will remember things.

Memory refuses to colonize.

Names do not.

Now the textbooks end.

They tell you about the expedition and then release her back into quiet with a shrug disguised as a flourish.

There is a rumor about her death—some say Fort Manuel Lisa, some say a later domestic geography where she becomes old and remembers too much.

But there is a longer truth: she returned to a marriage shaped like a trap, a culture shaped like a wound, a country shaped like a promise awaiting redemption.

She kept walking.

She kept doing small mercies that never become portrait.

Shock wants spectacle.

Sacagawea offers endurance.

She is not the knife; she is the hand that chooses not to cut and still finds food.

She is not the flag; she is the wind that teaches flags humility.

She is not the discovery; she is the path discoveries must kneel to in order to exist.

She lived the human math of colonization and refused to be its sum: capture plus marriage plus expedition does not equal property.

She remained person.

Her perilous childhood did not produce pity; it produced infrastructure.

She built within herself a country where men cannot legislate breath.

She learned to negotiate with mothers whose sons were demanded by the westward hunger.

She spoke gently to chiefs who remembered her as a child and met her as a woman carrying a baby and a nation’s ignorance.

She performed the scandal of kindness in a land trained to prefer violence.

She made maps using trust and repaired maps using apology.

Nightmare is a word we assign to marriages because it seduces audiences.

The truth is colder and more exact.

Charbonneau was a man who unlearned tenderness and replaced it with hunger.

He was not a monster; he was a symptom.

Sacagawea survived symptomology.

She medicated cruelty with competence.

She performed triage on a century and kept breathing.

She protected the child.

She built fences against darkness using names, places, people who owed her, people who loved her, people who feared her because fear is sometimes safer than indifference.

When the boy—Jean Baptiste, Pomp—grew old enough to remember, what did he remember.

Hands that secure him to a spine that refuses to break.

Voices in many tongues that find safety under a mother’s decisions.

Men who function as weather, sometimes generous, sometimes punitive, never gods.

A woman who ensures paper lives, instruments calibrate, maps remain.

He learned a definition of heroism no painting will hold: someone who keeps you alive while teaching you that survival is not the same as surrender.

They say she was tough, as if toughness were a single muscle.

She was many muscles arranged into a theology.

Toughness for her was listening to women cry about sons taken, then turning grief into negotiation.

It was telling a leader his pride endangered a winter and doing so without humiliating him, because humiliation invites war and war invites coffins.

It was helping men name animals they had never seen without letting them believe naming equals ownership.

It was deciding when to be visible to garner protection and when to be invisible to prevent harm.

It was sleeping light so the child sleeps deep.

She becomes myth properly only when we accept that the myth fails.

Statues make the baby lighter than it was.

Paintings make the river benevolent.

Essays arrange Lewis and Clark at the front of the procession because procession satisfies masculine hunger for order.

The real procession happens in the lungs.

The real monument is a mother’s spine.

The real shock is that a nation that insisted on inventory learned its borders from a woman who refused to be numbered.

If you require a collapse, here is one that fits: the collapse of the story told without her voice.

The collapse of the credit owed to men.

The collapse of the fantasy that endurance is quiet and therefore small.

The collapse of the lie that discovery is noble when it rests upon theft.

The collapse of the comfort that comes from believing courage looks like drawing lines on a map; courage looks like tying a child to your back and walking those lines until they become geography everyone must respect because you lived it.

She is haunted because land haunts everyone who misnames it.

She is holy because the body that carries another body becomes liturgy.

She is human because she could have broken a hundred times and did not, not out of pride but out of scene-setting: she was too busy arranging safety to collapse for audience.

Imagine the night after the canoe incident, after the journals are saved, after the compliments are awarded like medals that weigh nothing.

She lies down under sky shaped like apology, the baby breathes into her shoulder, Charbonneau mutters an inventory of blames.

She watches the stars and finds none willing to descend and help.

She decides, again, to keep going.

This decision is repeated until death.

This decision saves a nation from forgetting who taught it how to move through its own body.

In later rooms, men will debate her endings.

Did she die here or there, this year or that.

They will spend accuracy on a calendar because calendars can be owned.

They will avoid accuracy on a soul because souls embarrass owners.

Some say she became old, wore memory like a coat, told stories that corrected men.

Some say she died young and the earth took her back with the speed of storms.

The truth is layered like rivers: she continued until continuation was no longer offered.

The country continued using her instruction and refused to pay.

If America were honest, it would build its capital on a spine and admit who carried it.

If America were decent, it would teach children to tie history to their backs and walk toward empathy.

If America were brave, it would say her name properly and accept the shock that comes from honoring the person who taught survival to a nation that mistakes audacity for wisdom.

Sacagawea is not a symbol.

She is an instrument tuned against cruelty.

The final image the audience will permit: she steps into dawn, the boy presses his face to the cloth that smells like mother and river, the men follow, the land waits for her decision to begin.

She chooses a direction.

She does not require a blessing.

She carries the moon because men ask her to carry maps and gods ask her to carry endurance and children ask her to carry them.

The moon weighs less than all three.

She carries it anyway.

Shock lives in the gap between who is taught and who is forgotten.

She stands in that gap and refuses to be a statue.

A statue cannot correct course.

A statue cannot nurse.

A statue cannot threaten to take the map and leave when men behave as if lives are adjectives.

She is not stone.

She is weather.

She alters.

She instructs.

And the country, which loves its myths the way children love lies that make them feel large, will eventually learn to breathe her name without apology.

It will learn to tell the truth: that a teenage mother saved its memory from drowning, that a stolen child found a brother and didn’t collapse under the weight of two histories colliding, that a wife survived a marriage without making her survival into entertainment, that a woman taught men to ask permission from land.

It will learn the scandal: kindness beats conquest, and the west was not won; it was survived.

When she is gone, the river keeps its archive.

The journals keep their pretensions.

The nation keeps its posture.

But in kitchens, women keep telling daughters how to tie babies to backs.

In camps, elders keep reminding boys that maps begin with breath.

In classrooms that someday become brave, teachers keep confessing that the names written largest learned movement from hands written smallest.

And somewhere in the geography that believes itself divine, a path remains where footsteps taught the continent humility.

They teach you the rope and forget the hands.

Remember the hands.

They teach you the map and forget the heartbeat.

Remember the heartbeat.

They teach you Lewis and Clark and forget the mother who carried the moon.

Remember the mother.

And you will finally hear America gasp, not because it is shocked by danger, but because it has discovered, at last, who kept it alive.

News

“Boxing’s Biggest Event: Mayweather and Pacquiao Rematch for $600 Million in 2026!” -ZZ After years of speculation and anticipation, boxing icons Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao have officially confirmed their rematch, scheduled for September 2026, with a jaw-dropping $600 million on the line. This epic showdown is expected to reignite the fierce rivalry that captivated fans worldwide. What led to this long-awaited rematch, and how will both fighters prepare for this historic event? Get ready for an in-depth analysis of what this fight means for the future of boxing!

The $600 Million Showdown: Mayweather vs.Pacquiao II – A Clash of Titans In the arena of boxing, where legends are…

“Confessions of a Fan: My Love-Hate Relationship with Dana White!” -ZZ In an honest and candid reflection, I share my tumultuous journey with UFC President Dana White. Once filled with disdain for his controversial decisions and brash personality, I find myself wrestling with those feelings once again. What led to this complicated relationship, and how has my perception of White evolved over time? Join me as I explore the complexities of fandom and the impact of a polarizing figure in the world of mixed martial arts.

The Fall of a Titan: Dana White’s Controversial Maneuvers in the Fight World In the tumultuous realm of mixed martial…

“Browns Make Headlines: Todd Monken Releases Dillon Gabriel—What’s Next?” -ZZ In a stunning development, the Cleveland Browns have decided to part ways with quarterback Dillon Gabriel, as confirmed by offensive coordinator Todd Monken. This unexpected release raises questions about the team’s strategy moving forward and Gabriel’s next steps in his career. What prompted this decision, and how will it affect the Browns’ quarterback situation? Get ready for an in-depth analysis of this significant move in the NFL.

The Shocking Release: Todd Monken and the Fallout of Dillon Gabriel’s Departure In the high-stakes world of the NFL, where…

“Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford WEIGH IN: ‘There to be HIT!’ After Ryan Garcia’s Victory!” -ZZ In a thrilling post-fight analysis, boxing stars Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford shared their candid reactions to Ryan Garcia’s latest win. Highlighting the dynamics of the fight, they emphasized the opportunities and vulnerabilities that emerged in Garcia’s performance. What insights did these champions provide about Garcia’s style, and how might this impact future matchups in the boxing world? Join us as we break down their reactions and what they mean for the future of the sport.

The Aftermath of Glory: Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford React to Ryan Garcia’s Stunning Victory In the electrifying world of…

“Stefon Diggs: The Star Who Can’t Escape Controversy—What’s Really Going On?” -ZZ Despite his remarkable skills and contributions to the Buffalo Bills, Stefon Diggs finds himself entangled in controversy that he just can’t shake. From social media outbursts to strained relationships with teammates, the narratives surrounding him continue to evolve. What are the reasons behind his ongoing struggles to find peace and stability, and how will this affect his future in the NFL? Join us as we explore the intricate web of challenges facing Diggs.

The Unraveling of Stefon Diggs: A Star Caught in the Shadows In the dazzling world of the NFL, where talent…

“BREAKING: Shedeur Sanders’ Image Takes a Hit After Fernando Mendoza’s Controversial Call!” -ZZ In a dramatic turn of events, the carefully crafted narrative around Shedeur Sanders has taken a significant hit following Fernando Mendoza’s decision. As the college football world reacts to this unexpected twist, the implications for Sanders and his team’s future are becoming clearer. What does this mean for the young quarterback’s reputation, and how will it shape the upcoming season? Prepare for an in-depth look at the fallout from this shocking development!

The Fall of a Star: Shedeur Sanders’ Narrative Shattered by the Mendoza Decision In the world of college football, where…

End of content

No more pages to load