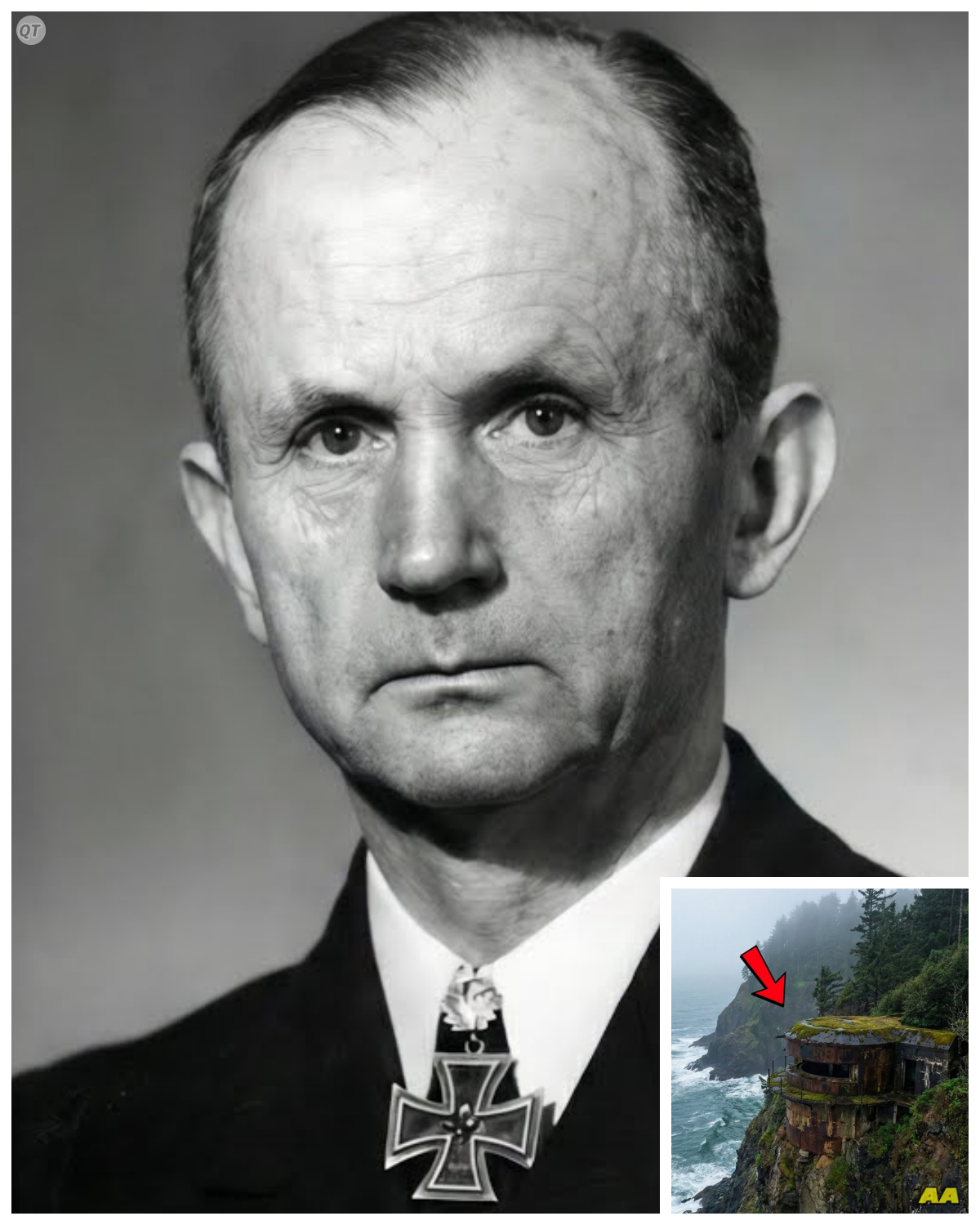

In September 2024, a hiking guide in Norway noticed something odd about a cliff face overlooking the barren sea.

The rock formation seemed too angular, too deliberate.

When he climbed closer, his hand touched concrete hidden beneath decades of moss and soil.

What he’d found was the entrance to a bunker that had been sealed for 79 years.

And inside was evidence of one of World War II’s strangest disappearances.

The bunker belonged to Viz Admiral Eric Bower, commander of German naval operations along the Arctic coast.

In April 1945, as the Third Reich collapsed, Bower sent a final encrypted message to Marine headquarters in Kio, maintaining observation.

Weather conditions optimal.

Then nothing, no evacuation order, no surrender, no body ever recovered.

The Norwegian resistance reported that Bower’s coastal observation post had been abandoned, but they never found where he’d gone.

Soviet forces who swept through the region weeks later found only empty installations and burned documents.

For nearly eight decades, Bower’s fate remained unknown.

His name appeared on no prisoner lists.

No grave was ever marked.

The German Naval Archives listed him simply as missing, presumed dead.

April 1945 until that hiking guide pushed aside the moss and discovered what Bower had been hiding.

That hidden bunker complex held answers that would rewrite the final chapter of Germany’s Arctic naval operations.

If you want to see what investigators found preserved inside after 79 years, including Bower’s final log book, hit that like button.

It helps us bring more forgotten stories like this to light.

and subscribe if you haven’t already so you don’t miss what we uncover next.

Now, back to the spring of 1945 when a mocked admiral made a decision that would puzzle historians for the rest of the century.

That hidden bunker complex held answers that would rewrite the final chapter of Germany’s Arctic naval operations.

If you want to see what investigators found preserved inside after 79 years, including Bower’s final log book, hit that like button.

It helps us bring more forgotten stories like this to light.

And subscribe if you haven’t already so you don’t miss what we uncover next.

Now, back to the spring of 1945 when a weremocked admiral made a decision that would puzzle historians for the rest of the century.

To understand why Bower vanished, we need to understand what he was protecting.

Vismiral Eric Bower wasn’t supposed to be in Norway at all.

By 1945, he should have been commanding a surface fleet, not isolated observation posts along the Arctic coast, but Bower had made enemies in Berlin.

In 1943, he publicly opposed Grand Admiral Donut’s strategy of concentrating Ubot in the Atlantic, arguing that the marine was neglecting the northern approaches that protected vital iron or shipments from Sweden.

The disagreement cost him his career trajectory.

Instead of a battle group, he got Norway’s northernmost sector, a punishment disguised as a command.

The posting came in August 1943.

Bower arrived at Hammerfest with a staff of 12 officers and orders to establish coastal observation stations monitoring Allied convoy activity heading to Merman.

The mission mattered more than Berlin admitted.

Every Soviet convoy that reached Mormont’s delivered tanks, aircraft, and ammunition that would eventually be used against German forces on the Eastern Front.

If the marine could identify convoy routes and timings, Yubot Wolfpacks could intercept them.

Bower’s observations fed directly into attack planning.

Bower took the assignment seriously.

Over 18 months, he built a network of seven observation posts stretching from Hammerfest to the Soviet border.

Each positioned on high ground with sight lines covering 30 to 40 m of ocean.

He recruited local Norwegian collaborators who knew the coast.

Fishermen who could distinguish between weather patterns and vessel wakes.

By early 1945, Bower’s reports were among the most detailed intelligence products the marine received from any sector.

But Bower was also preparing for something else.

In February 1945, he requisitioned construction supplies that made no sense for standard military operations.

Mining explosives, precision drilling equipment, reinforced storage containers rated for sub-zero temperatures.

His staff assumed he was fortifying existing positions.

They didn’t know he discovered a sea cave system beneath the cliffs near his primary observation post.

A geological formation that offered something no surface bunker could provide.

Complete invisibility.

The cave system had been formed by thousands of years of wave erosion, creating chambers that extended 200 ft into the rock face.

The entrance sat 60 ft above the waterline, accessible only by a narrow path that could be hidden from both air and sea observation.

Bower had been exploring these caves since October 1944, using his personal time and a handful of trusted engineers.

By March 1945, he’d built something inside them.

The official record shows Bower as a dutiful officer until the end.

His last routine report reached Keel on April 12th, 1945, 3 days after American forces crossed the Ela River into Germany’s heartland.

The report contained standard meteorological data and convoy sighting information.

Nothing suggested panic or planning for evacuation.

His staff officers later told Norwegian interrogators that Bower had seemed calm during those final weeks, almost relieved.

He said the war would be over soon, one officer recalled, and that he’d done what he needed to do.

None of them knew that Bower had been moving supplies into his hidden cave bunker for 6 months, or that he’d been communicating with someone outside the normal chain of command.

What Bower had built inside those caves would remain hidden until 2024.

But the network he’d created to supply it that fell apart within days of his disappearance, leaving a paper trail that intelligence officers wouldn’t notice for decades.

April 19th, 1945.

The spring thaw had started early that year, and the ice that normally choked Norway’s northern harbors was breaking up weeks ahead of schedule.

Bower held a final briefing with his staff at Hammerfest at 0800 hours.

According to the log maintained by Captain Litnant Werners, Bower’s operations officer.

The meeting lasted 12 minutes.

Bower confirmed observation schedules for the coming week and authorized destruction of sensitive documents as Soviet forces advanced from the east.

He mentioned nothing unusual.

At 1,030 hours, Bower departed Hammerfest in a staff car with his aid Aubberl and Hanskercher driving north along the coastal road.

The destination in the duty log read observation post 7 routine inspection.

OP7 was Bower’s northernmost station, positioned on cliffs overlooking the Baron Sea, operated by a rotating crew of three men.

The drive normally took 90 minutes.

Bower and Kercher were expected back by sunset.

They never returned.

At 1900 hours, when Bower hadn’t radioed in, Scholes attempted contact.

No response.

He tried Opie 7 directly.

The crew there reported that Bower and Kercher had arrived at 1,145 hours.

inspected the installation and departed at 1,315 hours.

They’d left heading south on the coast road back toward Hammerfest.

Somewhere during that 40-mile return journey, they vanished.

Scholes dispatched a search team at first light on April 20th.

They found Bower staff car at 0920 hours.

Parked on a cliffside overlook 6 mi north of OP7.

The vehicle was locked.

The keys were gone.

Inside the car, two empty thermoses, a map case containing standard issue charts, Kercher’s sidearm in its holster.

No sign of struggle, no blood, no personal effects.

The fuel tank was 3/4 full.

What made the scene stranger was what they found outside the car.

Tire tracks showed that Bower had pulled off the road deliberately positioning the vehicle to face the ocean.

footprints.

Two sets led from the car toward the cliff edge, then disappeared.

Not over the cliff, just ended as if Bower and Kercher had evaporated 30 ft from the drop.

The search team scoured the cliff base below.

No bodies in the rocks, no debris in the water.

The Norwegian resistance picked up the story within hours.

Their radio intercept station at Trump logged a brief encoded CRS marine transmission at 0340 hours on April 20th, 5 hours before the search team found the abandoned car.

The message originated from somewhere near the location where Bower disappeared.

It was sent on a frequency that Bower’s command didn’t officially use.

The resistance couldn’t decrypt it, but they noted the transmission time and approximate location.

British intelligence received the information 3 weeks later.

Too late to mean anything.

Back at Hammerfest, Scholes faced an impossible situation.

The war was ending.

Soviet forces were less than a week away.

His commanding officer had vanished without explanation.

On April 23rd, Scholes made the decision to evacuate.

He ordered all remaining personnel to destroy equipment, burn documents, and make their way west to potential evacuation points.

By April 28th, when Soviet forces reached Hammerfest, they found empty installations and coal fires.

But one thing Soviet intelligence did find buried in the ashes of Bower’s headquarters was a partially burned requisition form dated March 15th, 1945.

The form requested supplies for project Adler Eagle project.

The items list made no sense.

Chemical storage batteries, encrypted radio equipment, surveying instruments, and 3 months of concentrated rations for two people.

The requisition had been approved by Bower himself.

But the destination field was blank, just notation.

Field delivery coordinates provided separately.

The Soviets filed the document and moved on.

They had a continent to occupy and a war to finish.

One missing admiral didn’t matter.

The Norwegian government, when it took over the investigation in June 1945, found nothing more.

Bower staff officers interrogated separately, all told the same story.

Routine inspection, routine disappearance, no explanation.

Kercher’s family in Hamburg received notification that their son was missing, presumed dead.

Bower’s wife who lived in Ke received the same.

The file was closed in August 1945.

For the next 79 years, Viz Admiral Eric Bower existed only as a name on a list of officers who never came home until a hiking guide in Norway touched concrete hidden beneath moss and realized that Bower hadn’t disappeared at all.

He’d gone underground.

What that hiking guide found on the cliff face in 2024 would prove that Bower had been planning his vanishing act for months and that he hadn’t been working alone.

The official investigation into Bower’s disappearance lasted exactly 14 weeks before being shelved.

Norwegian authorities interviewed everyone who’d known the admiral, examined every document that survived the headquarters evacuation, and searched 20 mi of Coastline.

They found nothing that explained where he’d gone.

The theories started immediately.

The first and most popular was suicide.

The war was lost.

Bower had no future in postwar Germany.

Perhaps he’d walked into the ocean, waited down with stones, choosing to disappear rather than face capture.

The Norwegian investigators noted this theory in their report, but found it unconvincing.

Suicides don’t usually take their aids with them, and they don’t park their cars so carefully before jumping.

The second theory was defection.

British intelligence briefly considered whether Bower had been working as a double agent and had been extracted by submarine.

The timing fit.

British subs operated in those waters, but there was no evidence Bower had ever contacted Allied intelligence, and his operational record showed he’d been aggressively effective at his job, sinking Allied shipping through his convoy intelligence.

MI6 closed that line of inquiry in July 1945.

The third theory popular among Bower’s former staff was Soviet capture.

Perhaps a Soviet reconnaissance team had already penetrated that far west.

Perhaps they’d captured Bower and Kercher, transported them east, and kept them in a golag.

Stalin’s forces had snatched German officers before.

But when prisoner lists were finally exchanged after the war, Bower’s name didn’t appear.

The Soviets denied holding him.

The mystery deepened when researchers accessed Norwegian resistance archives in the 1960s.

The decoded summary of that strange radio transmission from April 20th, 1945 had been preserved.

The message was short.

Phase one complete.

Ceiling entrance.

Estimate 90 days.

Autonomy will monitor but not transmit until conditions permit.

The initials matched Eric Alberbower.

But if Bower had sent that message hours after supposedly disappearing, where had he transmitted from? And what was phase one? Even stranger was what the resistance network reported finding in May 1945 after the Germans had evacuated.

A fisherman from a village near OP.

Seven approached Norwegian authorities with a story.

In March 1945, he’d been hired by a German officer, description matching Bower, to deliver supplies to an installation along the coast.

The fisherman had been paid well and told to ask no questions.

He’d made three trips, carrying crates up a cliff path to a location the officer wouldn’t specify.

The fisherman said he’d been blindfolded for the final approach each time.

When Norwegian investigators asked him to show them a location, he led them to the cliff area where Bower’s car had been found, but he couldn’t identify the exact spot.

Somewhere up there, he said, gesturing at hundreds of yards of rock face.

A search team spent 2 days examining the cliffs.

They found nothing.

The rock was solid, broken only by natural crevices too narrow for a man to enter.

If Bower had built something up there, it was invisible.

The investigators concluded the fisherman was either lying or mistaken.

His story went into the file alongside all the other dead ends.

Bower’s wife, Martha, refused to believe he was dead.

She spent 10 years writing letters to military archives, prisoner assistance organizations, and search services.

In 1955, she traveled to Norway herself, retracing her husband’s last known route.

She stood where his car had been found and stared at the cliffs.

He’s there, she told a local reporter.

Somewhere in those rocks.

I know he didn’t leave.

She returned to Germany convinced but unable to prove anything.

She died in 1963, still listed as the wife of a missing officer.

The case faded from public memory.

Bower became a footnote in books about the Marine’s final days.

One of thousands of officers who disappeared during the war’s chaotic end.

Historians occasionally mention him as an example of how many German personnel simply vanished in 1945.

Their fates unknowable.

The mystery was filed under wartime chaos and forgotten.

But the cliffs kept their secret.

Through decades of Norwegian summers and Arctic winters, through the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, through the digital age and the rise of satellite surveillance, whatever Bower had built remained hidden.

The moss grew, the weather eroded, and the entrance stayed sealed until September 2024 when a hiking guide named Christian Shrenon decided to investigate an odd rock formation that didn’t look quite natural.

Between 1945 and 2024, the Norwegian coast, where Bower disappeared, was searched at least four times by four different groups using increasingly sophisticated technology.

Each time they found nothing.

The first serious attempt came in 1968 when a team of German war grave investigators returned to Norway as part of a broader effort to locate missing Wormach personnel.

They had Bower’s case file, the fisherman’s testimony, and two weeks of goodweather.

They brought metal detectors, the best available at the time, and systematically swept the cliff area.

The devices picked up spent shell casings, abandoned equipment from German installations, even a buried motorcycle from the occupation, but no bunker, no hidden entrance.

The team concluded that if Bower had built anything, it was probably in a location far from where his car was found.

They moved on.

The 1980s brought renewed interest, sparked by Norwegian television documentary about wartime mysteries.

A local history group in Hammerfest decided to investigate Bower’s disappearance using newly available technology, ground penetrating radar.

They spent 3 days scanning the cliff face in 1987, looking for hollow spaces behind the rock.

The radar showed natural cave formations common along that stretch of coast, but nothing that suggested human construction.

The entrance signatures they were looking for, right angles, concrete reinforcement didn’t appear on their scans.

They published a report concluding that the Bower bunker was probably a myth.

What they didn’t know was that they’d scanned 20 m too far south.

The cave entrance was outside their grid.

The end of a Cold War open new archives, including Soviet intelligence files captured by Norwegian forces in 1945.

A researcher in Oslo digging through these files in 1993 found a fascinating detail.

Soviet naval intelligence had sent a team to the area in May 1945 specifically looking for German observation posts.

Their report mentioned finding seven installations all the known OP locations but there was a handwritten note in the margin.

Local source reports eighth position location unknown constructed winter 1944 to 45.

Unable to verify, the Soviets had heard rumors, too.

They’d searched and found nothing.

By the early 2000s, satellite imagery covered every inch of Norway’s coastline.

Google Earth made it possible for anyone to examine the area where Bower disappeared.

Amateur historians zoomed in looking for bunker entrances, suspicious formations, anything that suggested a hidden structure.

They found nothing.

The consensus grew that if Bower had built a bunker, it was either completely destroyed by weather erosion or had never existed in the first place.

But technology wasn’t the problem.

The problem was that everyone was looking for a bunker that looked like a bunker.

They searched for concrete walls, metal doors, ventilation shafts, the standard signatures of military construction.

Bower had been smarter than that.

He’d built his installation inside a natural formation using the rock itself as camouflage.

The entrance was positioned on a slight overhang, invisible from above, hidden from sea level observation by the cliff’s curvature.

Unless you climb to that exact spot and look to that exact angle, you’d see only natural rock face.

And that’s exactly what Christianson did in September 2024 when he left the marked hiking trail to investigate what he thought was an interesting geological formation.

What Swenson found would prove that every search team for 79 years had been looking in the right place, but at the wrong height.

And what was inside Bower’s hidden complex would answer questions historians didn’t even know to ask.

Christian Shrenen worked as a hiking guide for a tourism company based in Toronto.

He’d been leading groups along Norway’s northern coast for 8 years and thought he knew every cliff face, every rock formation, every sight line in his territory.

On September 14th, 2024, he was scouting a new route when he noticed something odd.

The rock face looked wrong.

Not dramatically wrong, just angular in a way that didn’t match the surrounding geology.

The cliff was primarily granite, weathered into rounded formations by thousands of years of wind and water.

But this section had sharp corners, deliberate edges.

Shrenson climbed closer, using hand holds he’d normally avoid, working his way across a narrow ledge 60 ft above the water.

His hand touched concrete, not exposed concrete.

This was covered by moss liyken, camouflaged by decades of growth.

But underneath was smooth manufactured surface.

Shrenson cleared away the vegetation with his knife and found the edge of a form poured wall built directly into the natural rock face.

The construction was so precisely matched to the surrounding stone that from 10 ft away, it was invisible.

Shrenen followed the concrete edge.

20 ft along the ledge, he found the entrance.

The door was steel set into a concrete frame that blended seamlessly with the rock around it.

The door itself had been painted with textured coating that mimic lykan and rock patterns.

Nazier era camouflage technique.

79 years of weather had oxidized the steel and encouraged real moss growth, making the disguise perfect.

The door had no external handle, no markings, just a keyhole that had corroded shut decades ago.

Shrenson photographed everything.

marked the GPS coordinates and returned to Trumpo.

By September 16th, he’d contacted the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

By September 18th, a team was on site.

The recovery team included Dr.

Liv Hogan, a military historian from the Norwegian Defense Museum, Eric Johansson, a structural engineer with experience in historical bunker recovery, and two technicians from the Norwegian Fortification Heritage Office.

They reached a location on September 19th and confirmed Strenson’s finding.

This was a military installation, World War II era, completely hidden from casual observation.

Opening the door took 3 hours.

The corroded lock mechanism had to be carefully cut away to avoid damaging what might be inside.

At 1445 hours on September 19th, 2024, the door swung inward for the first time in 79 years.

The smell hit them first.

Stale air, but not rotten.

Not the smell of death.

Just decades of sealed atmosphere, dry and mineral sharp.

The team’s flashlights revealed a tunnel huned directly into the rock, reinforced with timber supports and concrete.

The tunnel descended at a 15° angle leading deeper into the cliff.

The walls showed tool marks.

This had been excavated by hand, probably using the mining explosives Bower had requisitioned in February 1945, 40 ft in.

The tunnel opened into a chamber.

The room was approximately 20 ft by 15 ft, carved from solid rock.

The ceiling had been smoothed and reinforced.

Electric lights hung from brackets, still intact, but obviously non-functional.

Along one wall, storage shelves made from salvaged ship timber, still holding supplies in deteriorated containers.

Along another, a radio station built into a desk with equipment that looked like it had been carefully shut down rather than abandoned.

And on a third wall, beneath a waterproof tarp that had mostly survived, a map table, and above it, observation logs and leatherbound notebooks.

Dr.

Hogan approached the table carefully.

The notebooks were arranged in chronological order, the last one dated April 1945, sitting on top.

She opened it, wearing conservation gloves.

The pages were dry, preserved by the cave’s consistent temperature and low humidity.

The handwriting was precise, controlled.

The entries were in German.

The last entry was dated April 20th, 1945, the day after Bower disappeared.

It read, “Final observation complete.

Soviet advance confirmed 60 km east.

Evacuation routes compromised.

Implementing autonomous protocol.

Sealing entrance as planned.

Project Adler enters phase 2.

Below that is signature.

Viz Admiral Eric Bower.

The team spent the next 6 hours documenting the chamber before removing anything.

What they found was extraordinary.

A complete survival bunker stocked for long-term occupation.

Chemical batteries that could have powered the radio for months.

Medical supplies in sealed containers.

Concentrated rations and tins that still bore mocked quartermaster stamps.

Water filtration equipment.

Cold weather clothing.

Even books, German literature, technical manuals, navigation guides.

But what shocked the investigators most was what they found in the deepest section of the chamber behind another sealed door.

a second room smaller containing two CS personal effects and a locked metal case.

Inside that case, documents, maps, encoded messages, and a letter written in German dated April 25th, 1945.

The letter was addressed to whoever finds this and signed by Eric Bower.

That letter would explain everything.

Why Bower vanished, what he was protecting, and what happened during the 79 years the bunker stayed sealed.

But before the team could read it, they had to understand what the rest of the bunker revealed.

The Norwegian team evacuated everything from Bowowers bunker over a 10-day period in late September 2024, working carefully to preserve both the artifacts and the site’s historical integrity.

Each item was photographed in place, cataloged, and removed for laboratory analysis.

What emerged was a picture of meticulous planning and desperate improvisation.

The radio equipment was examined first.

The set was a tail funentor, a standard wear mocked portable transceiver, but modified.

Bower or someone working for him had altered the power system to run on chemical batteries instead of generators, eliminating the need for ventilation that would have revealed the bunker’s location.

The modification was professional, suggesting trained expertise.

The radio’s frequency crystal showed signs of use.

This was an emergency equipment stored for potential use.

It had been operated.

More revealing were the log books.

Bower had maintained daily observation records from October 1944 through April 1945, tracking Allied convoy movements, weather patterns, and ice conditions.

But starting in January 1945, the entries change character.

Bower began recording details that had nothing to do with naval operations.

food consumption rates, battery performance, air quality, and sealed spaces.

He was testing the bunker’s life support systems while pretending to conduct routine observations.

The testing logs were meticulous.

January 15th, sealed chamber for 12 hours.

CO2 levels acceptable at hour 10, concerning at hour 11.

Ventilation modification required.

February 3rd, battery bank sustained radio operation for 8 hours continuous transmission.

Estimate 90-day capacity with monitoring schedule.

March 20th, water filtration system processed 40 L.

Output quality excellent system reliable.

Bower had been preparing to live underground for months.

The supply inventory told its own story.

The Norwegian team found rations for two people for approximately 120 days, 4 months.

Medical supplies included antibiotics, surgical tools, and morphine amples.

The clothing cache contained two complete sets of civilian clothes in different sizes, suggesting Bower had planned for himself and Kercher to eventually emerge in disguise.

Hidden in a sealed container, forged Norwegian identity papers blank except for photographs.

The photos showed Bower and Kercher in civilian clothing taken against a neutral background.

But the most revealing find was the locked metal case.

Inside beneath the letter, to whoever finds this were classified where mocked documents that should never have been in Bower’s possession.

The documents included detailed reports on convoy routes to Merman compiled from intelligence sources across the entire northern theater.

They included Enigma decryption keys for Allied naval codes, information that only senior intelligence officers should have accessed.

They included maps of Soviet defensive positions along the Arctic coast.

Far more detailed than standard tactical intelligence.

And they included something that made Dr.

Hogan immediately contact German military archives.

Plans for Yubot operations in 1946.

The plans were dated February 1945.

Clearly theoretical given that Germany surrendered in May.

But they revealed something important.

Seniors marine officers had been planning for continuation of the war beyond Germany’s expected defeat.

The documents referenced under Neon Adler.

Operation Eagle, a proposed strategy for submarine warfare conducted from Norwegian bases even after the fall of Berlin.

Bower’s project Adler wasn’t just a personal survival plan.

It was connected to a larger scheme.

German military historians when shown the documents identified the plans as part of a fringe operation proposed by hardline naval officers who refused to accept defeat.

The operation was never officially approved and was considered delusional by most were mocked leadership by April 1945.

But some officers, including Bower, apparently took it seriously enough to prepare for it.

The letter itself, when finally translated and analyzed, explained Bower’s motivation.

Written in clear, controlled handwriting, it read, “To whoever finds this chamber, I am Biz Admiral Eric Bower’s marine, commander of Northern Observation Sector 7.

I write this on the fifth day of April, 1945, knowing that Germany will surrender within weeks.

I am not fleeing justice.

I am not a coward.

I am preserving what will be needed when the truth becomes clear.

The high command believes the war is lost.

They are wrong.

The Bolevik advance will not stop at Germany.

Within a year, perhaps two, the Western Allies will realize their mistake in partnering with Stalin.

When they do, they will need intelligence on Soviet naval capabilities, Arctic operations, convoy vulnerabilities.

I have compiled that intelligence.

It is stored here.

I cannot surrender these documents to the Soviets.

They would use them to strengthen their position.

I cannot surrender them to the British or Americans now.

They would destroy them without understanding their value.

So I wait.

I will monitor Allied radio traffic.

When the political situation shifts, when the inevitable conflict with the Soviets begins, I will make contact and offer what I know.

Aubber Lutin Kercher accompanies me by his own choice.

We have supplies for 4 months.

We expect the political shift within that time.

If you are reading this and we are not here, we succeeded in making contact and departed.

If you find our bodies, we miscalculated.

I do not expect understanding.

I expect history to judge whether this decision was justified.

Eric Bower, visil, April 5th, 1945.

In the letter was dated 3 weeks before Bower’s disappearance.

He’d written it before implementing his plan, suggesting he’d been preparing the bunker as a long-term intelligence safe house, not an emergency hideout.

But one critical question remained.

If Bower and Kercher had entered the bunker on April 20th, 1945 with supplies for 4 months, where were their bodies? The bunker contained no human remains.

The sleeping area showed signs of use, but not of death.

The team found no graves in the surrounding area.

No evidence of burial.

Forensic analysis of the bunker provided more questions than answers.

Dust patterns on surfaces suggested the radio had been used after April 1945.

The area around the equipment was cleaner than elsewhere in the room, indicating repeated contact.

Food containers showed consumption patterns extending beyond the first month.

The log books contained entries dated through June 1945, written in Bower’s handwriting, but increasingly erratic.

The final entry dated June 28th, 1945, read, “No contact established.

Allied Soviet cooperation continues.

Situation assessment error.

Supplies exhausted.

Exiting tonight, destroy this record if possible.

” But the record wasn’t destroyed.

The notebooks remained.

and Bowerer and Kercher were never seen again.

The forensic team’s analysis of what happened next would rely on one final piece of evidence, something found not in the bunker, but recently declassified Soviet archives that nobody had connected to Bower’s case until 2024.

The final piece of the puzzle came from an unexpected source, the Russian Federal Archive in Moscow.

In October 2024, following the discovery of Bowers Bunker, a Norwegian researcher named Dr.

Anders Christophersonen began searching Soviet military records from the summer of 1945, looking for any mention of German personnel captured in northern Norway after the official surrender.

He found a report dated July 3rd, 1945, filed by Soviet NKVD unit operating near the Norwegian border.

The report described the capture of two German officers attempting to cross into Soviet control territory.

The report was brief.

Two were mocked officers, malnourished, disoriented, captured attempting infiltration 12 km south of Nickel.

Officers claimed to be defectors with intelligence materials.

Currently detained for interrogation.

The report included no names.

Soviet procedure at the time was to assign prisoner numbers immediately and use those for all documentation, but the report mentioned one detail that caught Christopherson’s attention.

Senior officer carried sealed documents in waterproof case claims knowledge of Allied naval operations.

Christopherson cross- referenced the date and location with Bower’s timeline.

July 3rd was 5 days after Bower’s final bunker log entry.

The capture location was approximately 40 km east of where Bower’s bunker was hidden.

A difficult but possible journey on foot through Arctic terrain.

Further searching revealed a follow-up report dated July 10th, 1945.

The interrogation had gone badly.

The senior officer refused to cooperate unless guaranteed he would speak to Soviet naval intelligence directly.

The junior officer appeared ill, possibly from exposure or malnutrition.

The documents they carried were examined by a local NKVD intelligence officer who determined they were naval observation logs, possibly authentic, possible intelligence value unclear.

The report recommended transferring both prisoners to a specialized interrogation facility in Merman for evaluation.

The transfer was scheduled for July 15th, 1945.

No further records exist.

Christopherson search transfer logs, prisoner manifests, interrogation reports from Mermont’s facilities.

Nothing.

The two officers simply disappeared from the Soviet bureaucratic record after July 10th.

This wasn’t unusual.

The Soviet prisoner system in 1945 was chaotic, overwhelmed by millions of German PS.

Recordeping was haphazard.

Prisoners died of disease, malnutrition, and untreated injuries by the thousands.

Deaths often went unrecorded and some prisoners, particularly those with intelligence value, were moved into secret facilities that kept no standard records.

Dr.

Hogan, working with Christopherson, conducted a final analysis of the evidence.

The timeline fit perfectly.

Bowerer and Kercher had remained in the bunker from April 20th to June 28th, 1945 to 67 days, just short of their planned 120-day capacity.

During that time, they’d monitored Allied radio traffic, waiting for signs of Western Soviet conflict that never came.

When supplies ran critically low, they faced a choice.

emerge in Norway and surrender to Allied forces who would treat them as war criminals or attempt to cross into Soviet territory and offer their intelligence in exchange for protection.

Bower chose the Soviets.

It was a miscalculation.

The intelligence he carried Arctic convoy routes, Allied naval codes from 1944 to 45, German ebo tactics had some value in July 1945, but not enough to guarantee protection for two German officers.

The Soviets took the documents and most likely disposed of the men who carried them.

No execution order was ever found.

No grave was ever marked.

But the pattern fits what happened to thousands of German prisoners in Soviet custody during the chaotic summer of 1945.

Interrogation, determination of limited value, transfer to a labor camp, and death from disease or exposure within weeks or months.

Records, if they ever existed, were never properly filed.

The sealed metal case that Bower carried out of his bunker on June 28th, 1945 never reached Soviet naval intelligence.

It likely sat on some NKVD clerk’s desk in a border station for weeks before being discarded as outdated information from a defeated enemy.

The documents Bower had preserved so carefully, the intelligence he believed would make him valuable to whichever side won the coming cold war became meaningless the moment he surrendered them.

The bunker remained sealed and hidden because Bower had never planned to return.

He destroyed the only map showing its location before departing on June 28th.

The final entries in his log book were meant as a record for historians, not as a guide back.

When he and Kercher walked away from the bunker for the last time, they left behind only evidence of their miscalculation.

Vismal Eric Bower spent 79 years listed as missing, presumed dead.

April 1945.

The truth is that he died in Soviet custody in the summer of 1945, probably in a camp whose records have been lost or destroyed.

His calculated gamble that the West would need his intelligence within months of Germany’s defeat, failed because the Cold War, when it came, moved slower than he expected and valued different intelligence than he possessed.

The bunker kept its secret not because it was perfectly hidden, but because Bower designed it to be temporary.

It was never meant to be found.

It was meant to be forgotten after he emerged and delivered his intelligence to whatever power would protect him.

The fact that it remained sealed for 79 years is evidence not of brilliant engineering, but of complete failure.

The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage has preserved Bowowers Bunker as a historical site.

The entrance remains open for research purposes, though it’s not accessible to the public.

The artifacts, log books, equipment, supplies are now held at the Norwegian Defense Museum in Oslo.

The documents Bower tried to preserve have been shared with German military historians.

What strikes visitors to the museum exhibition is how ordinary everything looks.

The rations are standard tissue.

The radio is a common model.

The notebooks are identical to thousands of other military logs.

Nothing about the artifact suggests extraordinary planning or desperate measures.

They look like the equipment of a routine military installation, not a secret intelligence safe house.

But that’s the point.

Bower spent 6 months building a bunker that would be completely invisible, stocking it with supplies that would raise no suspicions if discovered, and maintaining logs that read like routine observations.

His genius wasn’t in dramatic gestures.

It was a meticulous camouflage of both his installation and his intentions.

The tragedy is that all that planning, all that preparation was based on a fundamental miscalculation.

Bower believed the Western Allies would need his help within months.

He didn’t understand that the Cold War would develop slowly, that intelligence would be gathered by entirely new methods, that the naval tactics he knew so well would become obsolete within years.

Martha Bower never learned what happened to her husband.

She died in 1963, still believing he was somewhere in those Norwegian cliffs.

In a sense, she was right.

The bunker held his last voluntary actions, his final plans, his miscalculated hope.

What happened after he walked away? The Soviet capture, the probable death in some unmarked camp matters less than what he built and why he built it.

The rock face where Christian Shrenson found that concrete wall looks exactly the same as it did in 1945.

The entrance is open now, marked with historical signage, but from any distance, it’s still invisible.

Moss is regrown over the cleared areas.

Weather continues its slow work.

In another decade, if the site isn’t actively maintained, it will disappear back into the cliff.

News

🐕 California Governor CRUMBLES: Bezos’ SHOCKING Amazon Shutdown Sends Him into a SPIRAL—What’s Next? 🌪️ In a dramatic turn of events, the California governor is reeling after Jeff Bezos dropped the bombshell announcement of a massive Amazon warehouse shutdown! As the implications of this closure sink in, the pressure is mounting on the governor to respond decisively. Can he navigate this crisis and protect California’s economy, or will his leadership falter under the weight of this unexpected blow? The tension is thick as the fallout begins! 👇

California’s Descent: A Tale of Panic and Power In the heart of California, a storm was brewing. Governor Gavin Newsom…

🐕 California Governor’s 90-DAY COUNTDOWN: Fuel Supply COLLAPSE Looms—Is This His Biggest FAILURE Yet? 🔥 In a shocking revelation that has left the state reeling, the California governor now faces a ticking clock as experts warn that the fuel supply could collapse in just 90 days! With panic setting in and public outcry growing louder, his leadership is under intense scrutiny. Can he pull off a miracle to avert disaster, or will this crisis seal his fate as a failed leader? The pressure is mounting, and the stakes have never been higher! 👇

The Last Drop: California’s Fuel Crisis In the heart of California, a storm brewed beneath the surface. Governor Newsom, a…

End of content

No more pages to load