In March 2024, a Swiss property developer purchasing land near Interlockan made an unsettling discovery.

Behind a false wall in what appeared to be an ordinary alpine storage shed, she found a concealed entrance.

Beyond it lay a fully furnished underground chamber, wearmock dress uniforms still hanging in a wardrobe, German military map spread across a desk, and a leather briefcase containing identity documents for General Major Friedrich von Waldstein.

a man official records claimed died during the fall of Berlin in May 1945.

The briefcase also held Swiss bank deposit slips dated 1946, 1947, and 1948.

If von Waldstein perished in Berlin, who was making deposits in Switzerland 3 years after the war ended.

If you want to discover how a Wermach general supposedly killed in Berlin was living in a hidden Swiss villa for years after Nazi Germany’s defeat, hit that like button.

It helps us bring more buried chapters of history to light.

And if you haven’t subscribed yet, join us so you don’t miss our next investigation into the war’s unfinished stories.

Now, back to that concealed chamber in the Alps.

The documents scattered across that underground desk would force historians to rewrite the final chapter of one of the Wormach’s most enigmatic officers.

In early 1945, Germany’s strategic situation had collapsed beyond recovery.

The Red Army stood at the Oda River just 35 mi from Berlin.

In the west, Allied forces had crossed the Rine.

The Third Reich’s remaining territory shrank daily.

Yet certain highranking officers received puzzling orders.

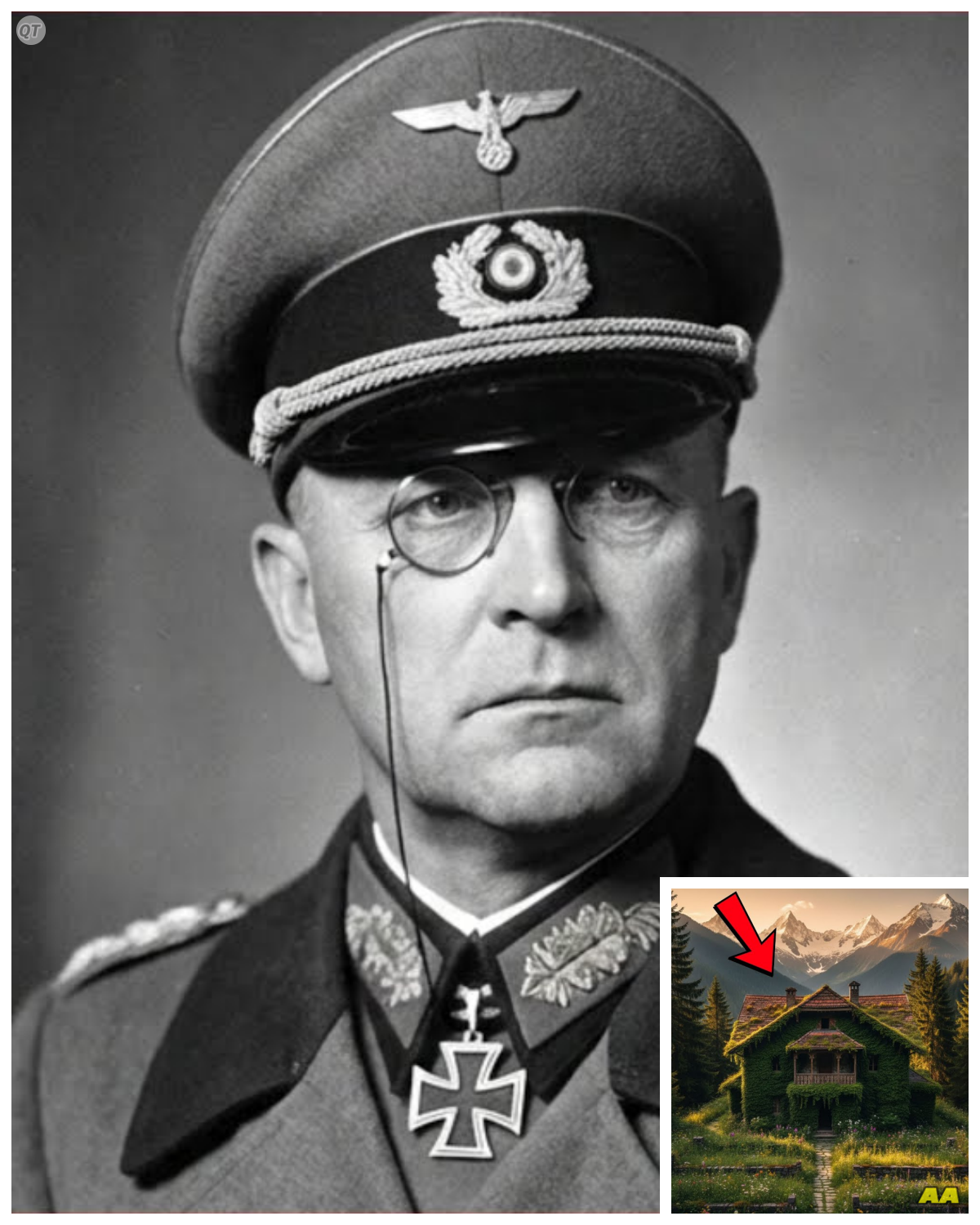

General Major Friedrich von Waldstein, 43 years old and commander of the 389th Infantry Division, was abruptly recalled from the Eastern Front on April 12th, 1945 and ordered to report directly to the Furer bunker in Berlin.

Von Waldstein’s military career had followed an unusual trajectory.

Born in 1902 to minor pressure nobility, he joined the Reichkesear 1920 and spent the inner war years as a logistics officer.

Hardly the combat pedigree that typically led to divisional command.

His rapid promotion in 1943 raised eyebrows among mocked insiders.

Intelligence documents from British MI6 declassified in 2008 noted that von Waldstein had extensive contacts in Switzerland dating to the 1930s when he served as assistant military attache in burn from 1936 to 1938.

During this posting he married Heidi Brunner, daughter of a prominent Zurich banker.

The 389th Infantry Division itself existed more on paper than in reality by April 1945.

Originally formed in December 1943, it had been shattered during operation bagration in summer 1944.

Hastily reconstituted with Luwaffer ground personnel and teenage conscripts, then ground down again in East Prussia.

By the time Bon Waldstein received his Berlin summons, his division numbered fewer than 800 effective combat troops, barely a reinforced battalion.

Why Hitler’s headquarters would recall such an officer from a phantom command to the doomed capital mystified von Waldstein’s subordinates.

Lieutenant Hans Keller, von Waldstein’s agitant, later testified to American interrogators that his commander seemed unsurprised by the orders.

He told me the division was finished anyway.

Keller recalled in a 1947 deposition now housed at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

He said Berlin needed officers who understood logistics and supply networks.

Then he asked me to burn his personal papers from the division headquarters correspondence mainly.

I thought nothing of it at the time.

Von Walstein departed for Berlin on April 14th.

Traveling by staff car through roads clogged with refugees and retreating Worermmont remnants.

His driver, Corporal Auto Briner, survived the war and gave testimony to Soviet investigators in 1946.

Brener stated they reached Berlin’s outskirts on April 16th, the day the Red Army’s final offensive began.

Von Waldstein dismissed Brener at a checkpoint in the Tear Garden district, telling the corporal to attempt escape westward toward American lines.

Brener succeeded, was captured by the US 9th Army in late April, and spent 2 years in Allied custody before repatriation.

The strategic situation von Walstein entered was apocalyptic.

Over 2.

5 million Soviet troops supported by 6,250 tanks and 41,600 artillery pieces encircle Berlin.

The city’s defenders comprised perhaps 45,000 Wormach soldiers supplemented by 40,000 folkster militia and remnants of SS units, many consisting of foreign volunteers and teenage Hitler youth.

Food supplies would last perhaps 10 days.

Ammunition stocks had dwindled to critical levels.

The furer bunker itself, located beneath the Reich Chancellory Garden at a depth of 55 ft, housed Hitler as close as staff and a rotating cast of military officers summoned for increasingly surreal situation conferences.

Von Waldstein’s activities during his nine days in Berlin remained obscure for decades.

Wearmock personnel records such as survived the war’s chaos listed him as arrived Berlin April 17th, 1945 with no subsequent entries.

The furer bunker telephone log partially preserved and captured by Soviet forces showed three calls placed to Genmash Waldstein on April 18th, 2022, but no details of the conversation’s content.

What little emerged came from fragmentaryary witness accounts that often contradicted one another.

Major General Helmouth Widling, Commander Bron’s defense, mentioned von Waldstein once in his postwar memoir.

Among the officers arriving daily at the bunker were many I did not know, staff types, logistics experts, men whose units had ceased to exist.

One such was Von Waldstein, who attended two situation conferences but said little.

His area of expertise was unclear to me.

The last definitive sighting came on April 25th at approximately 1,400 hours.

SS Sturman forer Eric Kempka, Hitler’s personal chauffeur, later testified that he encountered von Waldstein in the upper bunker level near the emergency exit.

He wore a wear mocked great coat over his uniform and carried a leather map case.

Kempa told American interrogators in October 1945.

I asked if he had orders to leave the bunker.

He showed me a movement authorization signed by General Krebs.

It permitted him to exit for liaison purposes with units in the Tier Garden sector.

I thought it’s strange.

There were barely any coherent units left to lies with.

After 1400 hours on April 25th, Friedrich von Waldstein vanished from documented history.

No one reported seeing him return to the bunker.

No one claimed to witness his death.

The Soviet forces that stormed the Reich Chancellery on May 2nd found no body matching his description.

His name appeared on no prisoner lists, neither Soviet nor Western Allied.

The immediate chaos of Berlin’s fall made individual fates difficult to track.

The Red Army took approximately 100,000 prisoners during the battle.

Corpses, military and civilian, numbered in the tens of thousands, many burned beyond recognition.

Others buried in mass graves or left to decompose in rubble for weeks.

Thousands of German soldiers attempted escape through Soviet lines in the final hours.

Most eye trying, some succeeded.

Initial Soviet intelligence reports compiled in June 1945 listed von Waldstein among the presumed dead based on his last known location.

The Wormach surrender rendered such distinctions largely academic.

Dead or captured.

The outcome for most officers differed little.

American counter intelligence.

Compiling lists of wanted personnel for potential war crimes investigation.

Mark von Walstein’s file status unknown.

Presumed KIA Berlin.

His case lacked the urgency surrounding SS officers or concentration camp personnel.

By autumn 1945, von Walstein’s wife, Heidi, still residing in her family Zurich apartment, received unofficial notification through Wormach Veterans Networks that her husband was missing and presumed killed during the battle for Berlin.

No body could be identified.

No grave site existed.

This lack of closure was distressingly common.

Hundreds of thousands of German servicemen simply disappeared in the war’s final months, their fates unknowable.

In December 1945, the Swiss Federal Police received an anonymous tip, suggesting that certain were mocked officers had used pre-arranged networks to escape Germany in the war’s final days.

The informant claimed that some had utilized contacts in Switzerland dating to the pre-war period, entering the country with forged identity papers.

Swiss authorities, keen to distance themselves from any suggestion of Nazi collaboration, conducted a prefuncter investigation that produced no results.

Their official report declassified in 1995 concluded that while individual Germans might have entered Switzerland illegally in 1945, no evidence suggested organized escape networks or highranking officers among the refugees.

What authorities did not know or chose not to pursue was that Friedrich von Waldstein had maintained a numbered account at Basler Handles Bank since 1937.

The account’s existence only emerged during a comprehensive audit of Swiss banking relationships with Naziera clients in the late 1990s.

Investigators found records showing the account remained active until 1952, with deposits continuing well after von Walstein supposed death.

The bank’s position was that accounts could be accessed by anyone with proper authorization codes.

Activity alone proved nothing about depositors identities.

Heidi von Waltstein never remarried.

She applied for and received a German widow’s pension in 1951 based on her husband’s presumed death in Berlin.

Swiss records show she lived quietly in Zurich until her death in 1983, occasionally visiting the Interlockan region for summer holidays.

Her will probated through a Zurich law firm, left her estate to her sister’s family, and made no mention of property in the Bernese Overberland.

Meanwhile, occasional rumors circulated among Wermach veteran networks about officers who had slipped away in 1945.

These stories typically combined fact with fantasy, describing elaborate escape routes through Denmark to Argentina or secret submarine voyages to Spanish ports.

Serious historians dismissed such tales as conspiracy theories, noting that the vast majority of were mocked officers either died in combat, committed suicide, or entered Allied captivity.

The documented cases of successful escapes involved mostly mid-level SS officers who had both motive and resources.

War criminals fleeing prosecution.

Von Waldstein’s case generated no particular interest because his wartime role appeared unremarkable.

He held no position in the Holocaust machinery.

His division committed no documented atrocities.

His recall to Berlin seemed administrative rather than sinister.

Without evidence of war crimes, Western intelligence services saw no reason to pursue the matter beyond marking his file closed in 1947.

Soviet records told a different story, though these remained locked in Moscow archives until the 1990s.

NKVD investigators had compiled a list of where mocked officers whose whereabouts remained unconfirmed after the Berlin battle.

Von Waldstein appeared on this list with a notation Swiss connections.

Investigate further.

A follow-up report from August 1946 stated that inquiries through Soviet intelligence contacts in Switzerland had yielded nothing concrete, merely rumors of German nationals living under false identities in remote Alpine villages.

The trail went cold.

The mystery might have remained academic except for one detail that emerged decades later.

Von Walstein’s sister Anna living in Munich continued receiving occasional letters postmarked from Interlockan throughout the late 1940s.

She mentioned these letters to her daughter in the 1970s, noting they were insigned, but contained references only her brother would know.

Anna died in 1979 and her daughter interviewed by a German television documentary team in 2009 recalled her mother saying, “I think Friedrich made it out somehow, but I never asked too many questions.

It was better not to know.

” Through the 1950s and 1960s, the story of Nazi Germany’s collapse was written and rewritten by historians, memoirs, and journalists.

The focus centered on major figures.

Hitler’s suicide, Gobble’s death, the fates of Goring and Spear.

Thousands of lesserknown officers faded into statistical obscurity.

Their individual stories lost among the millions of casualties.

Von Walstein became one name among many in Wermach casualty databases marked missing.

Presumed killed in action.

Berlin, April/May 1945.

The few researchers who stumbled across anomalies in von Waldstein’s case file found insufficient material to pursue deeper investigation.

His Swiss banking relationship appeared routine for an officer who had served in burn before the war.

His wife’s continued residence in Zurich was unremarkable.

Many German nationals lived in Switzerland.

The anonymous 1945 tip to Swiss police was one of hundreds received in that chaotic period.

Most proved unfounded.

Technological limitations hampered any potential investigation.

Without digital databases, cross- refferencing Swiss property records, banking activity, and witness testimonies across borders required enormous manual effort.

Switzerland’s banking secrecy laws rigidly enforced until international pressure mounted in the 1990s, made accessing financial records nearly impossible.

Even if investigators suspected von Walstein survived, proving his presence in Switzerland would require his numbered count records, which the bank refused to release without legal compulsion.

Geopolitical factors also played a role.

Switzerland’s delicate position during the Cold War made the government reluctant to probe too deeply into wartime arrangements that might embarrass powerful banking interests or reveal uncomfortable truths about neutrality’s compromises.

The country faced enough criticism for its gold transactions with Nazi Germany, pursuing every rumor about where mocked fugitives seemed counterproductive to national interests.

By the 1980s, the generation with personal memory of 1945 was aging.

Veterans died, taking their recollections with them.

The files were archived, then forgotten in basement storage.

The property near Interlockan, where von Waldstein allegedly lived, changed hands multiple times.

Each transaction handled through a Zurich law firm representing an anonymous trust.

Local residents, if they remembered a German-speaking man living reclusively in the 1940s and early 1950s, attributed nothing unusual to it.

The area had hosted refugees and displaced persons of many nationalities.

A brief resurgence of interest occurred in 1997 when Swiss banks faced international pressure to audit Nazi accounts.

Investigators combing through Basler Handles Bank records flagged von Waldstein’s numbered account as showing suspicious post 1945 activity.

However, the account had been closed in 1952 and the bank’s internal records from that period were sparse without living witnesses or documentary evidence of who accessed the account.

Investigators could prove nothing.

The case was noted in a footnote of a 700page report and promptly forgotten again.

The property itself, a modest chalet style structure on three hectares of alpine land, never attracted attention.

Titled to a holding company registered in Zug, it appeared on tax roles as a seasonal residence.

The Swiss system allowed considerable privacy for such arrangements, particularly if property taxes were paid punctually and no complaints arose from neighbors.

The underground chamber remained concealed behind that false wall, undetected through seven decades of minimal maintenance and occasional brief inspections.

In January 2024, the Zugregistered holding company that owned the interlockan property dissolved following the death of its final trustee, a 91-year-old Zurich attorney named Klaus Hoffman.

Hoffman’s estate went into probate, revealing he had managed the property trust since 1982, inheriting the responsibility from his father, Wernner Hoffman, who established the arrangement in 1951.

The trust document specified the property should be liquidated upon Klaus Hoffman’s death with proceeds donated to a Munich veterans charity that had ceased operating in 1994.

The property passed to Hoffman’s estate executive who listed it for sale through a burn real estate agency.

Developer Suzanne Krebs, specializing in converting older structures into boutique tourist accommodations, purchased it in February 2024 for 1.

2 million Swiss Franks, roughly market value for such properties.

She planned to assess the buildings for potential renovation or demolition, then construct a small hotel taking advantage of the spectacular alpine views.

Krebs first inspected the property on March 8th, 2024, accompanied by a structural engineer and an architect.

The main chalet showed typical deterioration from decades of minimal upkeep, damaged roof tiles, rotted window frames, outdated electrical systems.

The storage shed, a stone structure measuring approximately 4 m x 6 m, seemed unremarkable until the engineer noticed an anomaly.

The building’s external dimensions didn’t match its internal space.

The interior appeared roughly 2 m shorter than exterior measurements suggested.

Using thermal imaging equipment, technology that has revolutionized building assessment in recent years, the engineer detected a void behind the shed’s rear wall.

Krebs, assuming she had discovered an old root cellar or forgotten storage space, hired contractors to investigate.

On March 12th, workers carefully removed what appeared to be a solid stone wall, revealing it was actually a false facade attached to a steel frame.

Behind it, a steel door stood closed, but unlocked.

Beyond the door lay a chamber approximately 20 square m in size, carved into the hillside and lined with concrete walls.

The room contained a bed frame with rotted mattress, a wooden desk and chair, a wardrobe, a small bookshelf, and various personal items.

a ventilation shaft led upward, concealed on the surface by what appeared to be a natural rock outcropping.

Most remarkably, the chamber showed no signs of water intrusion or significant deterioration, though dust covered every surface.

Krebs immediately recognized wearmocked insignia on the uniforms hanging in the wardrobe.

Swiss law requires reporting discoveries of potential historical significance.

So she contacted the burned cannon police on March 13th.

Officers secured the site and contacted the Swiss Federal Office of Culture which dispatched Dr.

Stefan Richter, a historian specializing in World War II.

RTOR arrived on March 15th and spent 3 hours conducting a preliminary assessment.

The leather briefcase on the desk contained the most significant discoveries.

Inside were identity documents in the name of Herman Brandt, a Swiss passport issued in 1946, residence permits for Burn Canton, and various personal papers.

However, a false bottom in the briefcase revealed a second set of documents, Friedrich von Waldstein’s wear identity card, his officer’s commission signed by Field Marshall Vonrochic, and a small address book.

Also hidden, deposit slips from Basler Handles Bank dated between 1946 and 1948.

All referencing the same account number.

Photographs found in a desk drawer showed a man in civilian clothes against alpine backgrounds, sometimes alone, occasionally with an unidentified woman.

Comparison withm mock personnel photos confirmed the man was Friedri von Waldstein aged noticeably from his official wartime portraits but unmistakably the same person.

The most recent photograph appeared to date from the late 1940s or early 1950s based on clothing styles and photographic paper analysis.

Dr.

Richtor recognized the discovery’s significance immediately.

We were looking at evidence that a Wormach general officer, officially presumed dead in 1945, had not only survived but lived in Switzerland for years afterward.

He later told Swiss television, “This wasn’t just a hidden room.

It was a preserved snapshot of a clandestine existence.

” Swiss authorities established a joint investigative team comprising historians from the University of Burn, forensic specialists from Zurich Cannel Police and representatives from the German Federal Archives in Berlin, the team began systematic documentation of the site on March 20th, 2024.

employing techniques ranging from traditional archival research to cutting edge forensic analysis.

The chamber itself received comprehensive examination, forensic dating of concrete samples using radioactive isotope analysis, confirmed construction between 1945 and 1947, consistent with immediate postwar timelines.

The steel door and frame bore manufacturers markings from a Swiss industrial supplier in Zurich with company records showing a large order of security doors placed in May 1946 by a construction firm that dissolved in 1953.

The ventilation system, while simple, showed sophisticated design, indicating whoever built the chamber understood the necessity of long-term habitability.

Every item in the chamber was cataloged, photographed, and analyzed.

The wear mocked uniforms included von Walstein’s dress tunic with his decorations still attached, the iron cross first class, the eastern front metal, and several campaign ribbons.

Chemical analysis of fabric deterioration patterns suggested the uniforms had hung undisturbed since approximately 1950.

The wardrobe also contained civilian clothes from the late 1940s, suits, shirts, and shoes of good quality, all manufactured in Switzerland.

The bookshelf revealed von Waldstein’s reading material, military history, several novels by remark, a German Bible, and multiple maps of South America, particularly Argentina and Chile.

Handwritten notes in the margins of a 1947 Baker guide to Argentina suggested he was planning or considering immigration.

One notation read, “Buenous Aries, German community established.

Investigate further.

” This discovery sparked immediate speculation about whether von Waldstein had originally intended Switzerland as a temporary refuge.

The address book proved an investigative gold mine.

It contained approximately 40 entries, most using only first names or nicknames alongside phone numbers and addresses.

Cross-referencing these entries with Swiss residential directories from the 1940s and 1950s, researchers identified at least 12 individuals as wearmock veterans who had served in Switzerland as military attaches or liaison officers during the 1930s.

Another six entries corresponded to Swiss nationals with banking or legal backgrounds.

Several names remained unidentified, possibly representing contacts one Waldstein chose to obscure even in his private records.

Forensic analysis of documents employed multiple techniques.

The Swiss passport issued through Herman Brandt underwent detailed examination at the Swiss Federal Archives Authentication Laboratory.

While the passport itself was genuine, printed on authentic Swiss government paper with correct security features.

records showed no birth certificate, residency documentation, or prior identity papers for any Hermmont brand matching the physical description.

The passport had clearly been obtained through fraudulent means, likely requiring insider assistance from Swiss bureaucracy.

The deposit slips led investigators back to Basler Handles Bank, now operating as part of a larger Swiss banking conglomerate.

Under court order, the bank released historical records for von Walstein’s account.

These revealed a pattern.

Large deposits in 1937, 1938, and 1939, followed by minimal activity during the war years, then resumption of transactions in March 1946.

Between March 1946 and September 1952, the account received 20 new deposits ranging from 5,000 to 25,000 Swiss Franks.

Substantial sums worth hundreds of thousands in today’s currency.

Withdrawals occurred regularly, suggesting living expenses.

The account was closed in October 1952 with the remaining balance approximately 80,000 Franks transferred to an account at a different bank that subsequently merged out of existence.

Researchers traced the Hoffman family’s involvement.

Wernern Hoffman, who established the property trust in 1951, had been a junior attorney at a Zurich law firm in the 1930s.

The same period von Waldstein served at the German embassy.

Swiss immigration records showed Hoffman made several trips to Germany between 1936 and 1938, ostensibly on business.

After the war, Hoffman established an independent legal practice handling discrete estate matters for wealthy clients.

His personal papers, now held by his son’s estate, contained one telling entry in a 1946 diary, arranged property matter for HB.

Monthly retainer established.

The investigation expanded to Germany, where researchers at the Federal Archives in Berlin reviewed von Walstein’s complete military file.

They discovered something previous researchers had missed.

a 1944 memo from the Wormach High Command noting that von Waldstein had excellent administrative capabilities in financial logistics and supply procurement.

Further investigation revealed that in 1943 and 1944, von Waldstein’s division received unusually favorable allocations of fuel, ammunition, and equipment compared to similar units, suggesting possible influence beyond normal supply channels.

Dr.

Elizabeth Hartman, a forensic historian from Munich’s Institute for Contemporary History, examined Von Waldstein’s recall to Berlin in April 1945 with fresh perspective.

“The timing is suspicious,” she noted in her preliminary report.

“Officers were called to the furer bunker in the final days typically had specific purposes.

Last ditch defensive planning, negotiation attempts, or administrative tasks related to the regime’s dissolution.

” Von Waldstein’s logistics expertise suggests he might have been involved in asset transfers or evacuation planning.

This theory gained support when researchers discovered a previously overlooked document in Soviet archives.

A May 1945 NKVD intelligence summary noted that substantial quantities of Reich assets, including currency, gold, and negotiable instruments remain unaccounted for from the Reichkes Bank and were mocked logistics departments.

The report specifically mentioned that several officers with financial responsibilities disappeared during the Berlin battle.

Their fates and the resources under their control are unknown.

British MI6 files partially declassified in 2021 contained another intriguing fragment.

An April 1946 intelligence assessment stated, “We mocked officers with Swiss connections and financial expertise are suspected of having prepositioned assets in neutral territory.

Recommend monitoring of Swiss banking activity for suspicious transactions by German nationals.

The document listed eight names for observation.

Friedrich von Walstein was the third name on that list.

Perhaps most revealing was a discovery of a letter fragment found wedged behind a drawer in von Waldstein’s desk.

The letter dated July 1948 and written in German was addressed to F and signed H.

Almost certainly Heidi’s wife.

The surviving portion read.

Cannot risk more frequent visits.

The situation remains delicate.

Klaus assures me the arrangements are secure, but I fear complications.

Please do not send more letters to the Zurich address.

If necessary, the remainder was torn away.

The accumulated evidence allowed investigators to reconstruct Friedrich von Waldstein’s escape with reasonable certainty.

The story that emerged was one of careful planning, convenient timing, and exploitation of networks established years earlier.

Von Waldstein likely began planning his escape as early as 1943 when Germany’s strategic situation started its irreversible decline.

His pre-war posting in Switzerland provided crucial contacts, Swiss attorneys, bankers, and businessmen who could facilitate financial transactions and document procurement.

Between 1943 and 1944, he systematically transferred funds to his Swiss account, possibly through mocked logistics operations that gave him access to various financial resources.

These weren’t necessarily stolen funds.

Officers of his rank received substantial salaries and allowances, but the timing suggests deliberate preparation.

His recall to Berlin in April 1945, investigators now believe, was not to serve in the bunker’s last stand, but to facilitate his disappearance.

The movement authorization shown to SS Officer Kempka, was likely genuine.

Issued to allow Von Waldstein to exit the bunker with legitimate cover.

Once outside on April 25th, with Berlin’s collapse accelerating and chaos consuming the city, Von Waldstein simply walked away.

He discarded his weremocked identity documents, retained whatever portable assets he had brought to Berlin, and began moving westward.

Precisely how von Waldstein traversed Germany in late April 1945 remains unclear, but several factors worked in his favor.

By April 26th, Berlin was completely encircled, but Soviet forces still pushed westward, creating fluid combat zones where a resourceful officer in civilian clothes could potentially infiltrate retreating wear columns or displaced refugee streams.

Moreover, von Waldstein spoke fluent French from his pre-war service, useful if intercepted by Western Allied forces.

Evidence suggests he reached southern Germany by early May, possibly traveling through American controlled territory.

US occupation forces overwhelmed by millions of prisoners, refugees, and displaced persons, conducted screening operations that range from thorough to cursory depending on the situation.

A former weremocked officer without SS affiliation presenting as a civilian refugee might pass through without intensive interrogation, particularly if he carried documents suggesting non-military status.

The critical moment came at the Swiss border, likely somewhere along the Rine between Basil and Lake Constants.

Switzerland, while officially maintaining strict border controls, faced enormous practical challenges in May 1945.

Thousands of displaced persons attempted entry and Swiss border guards handled each case based on available resources and political considerations.

Von Waldstein’s pre-war connections became decisive here.

Warner Hoffman, the attorney, likely arranged for von Walstein’s Herman Brandt identity documents to be ready for pickup, possibly through an intermediary.

With a Swiss passport, even a fraudulently obtained one, and sufficient funds to demonstrate self-sufficiency, von Walstein could enter legally as a Swiss national returning home.

He likely arrived in Switzerland by June or July 1945, settling initially in Zurich with assistance from Hoffman’s law firm.

His wife Heidi’s role in the scheme remains ambiguous.

Evidence suggests she knew her husband survived but maintained plausible deniability by continuing to reside openly in Zurich while von Walstein lived in a concealed alpine chamber.

Her acceptance of a German widow’s pension in 1951 was either pragmatic deception or genuine uncertainty.

Investigators found no proof she visited the interlock and property before the 1950s, though she may have met her husband elsewhere.

The Alpine Chamber was likely constructed in 1946 as a secure refuge where Von Walstein could live if Swiss authorities began investigating German nationals more aggressively.

The location near Interlockan in a sparsely populated area accessible only by difficult mountain roads provided isolation while remaining within reach of Zurich and its banking services.

Von Waldstein may have spent weeks or months at a time in the chamber, particularly during periods when Swiss authorities conducted immigration checks.

The deposits to his Basler Handles bank account between 1946 and 1952 probably came from assets he accumulated during the war and successfully transferred to Switzerland.

The amounts totaling several hundred,000 Swiss Franks were substantial but not spectacular enough to attract attention in a banking system handling numerous large transactions.

He lived frugally drawing modest withdrawals for expenses while preserving capital.

Why did his clandestine existence end in 1952? Several possibilities exist, none conclusively proven.

The account closure and apparent cessation of activity at the Alpine Chamber suggest either death, departure from Switzerland, or transition to a more secure identity.

The maps of Argentina and notes about Buenus Aries indicate immigration was contemplated.

The 1950s saw significant German immigration to South America, often facilitated by networks ranging from humanitarian aid groups to more sinister organizations assisting former SS officers.

No death certificate exists for either Friedrich von Walstein or Hermon Brandt in Swiss records.

No departure is documented in Swiss immigration logs, though these become less reliable for the 1950s period.

Investigators working the case in 2024 checked Argentine immigration records from 1950 to 1955 for both names, finding no matches.

Though absence of records proves little given that periods, administrative chaos and the ease with which documents could be falsified.

The most plausible scenario according to Dr.

for heart monitor team is that von Waldstein successfully immigrated to South America around 1952, possibly using yet another false identity.

The closure of his Swiss account, the abandonment of the chamber sealed but not destroyed, and the transfer of the property to Hoffman’s trust all suggest a planned departure rather than sudden death.

He left the chamber as a kind of insurance policy.

Hartman speculated in her final report.

If his new identity in South America failed, he could potentially return to Switzerland and resume using the Herman Brandt documents.

What remains undisputed is that Friedrich von Waldstein, contrary to seven decades of historical record, did not die in Berlin.

He survived the war, successfully escaped to Switzerland through planning and connections established before Germany’s defeat, lived clandestinely in the Alps for approximately 7 years, and then vanished again, possibly to South America, possibly to elsewhere, his ultimate fate still unknown.

The discovery near Interlockin and forced one small but significant revision to the historical record.

Friedrich von Walstein’s name has been removed from the casualty lists and reclassified as escaped fate unknown.

His case joined the estimated several hundred were mocked and SS officers who successfully evaded capture and prosecution in the war’s chaotic final months.

A number far smaller than conspiracy theorists suggest, yet larger than official histories once acknowledged.

What makes van Waldstein’s story remarkable is not that he escaped.

Others did as well.

But that physical evidence of his escape remained hidden and intact for 79 years.

That sealed alpine chamber with its uniforms and documents and mundane personal effects offers a tangible connection to a moment when a defeated officer chose survival over honor, self-preservation over accountability.

The moral weight of that choice remains for others to judge.

The chamber itself has been preserved as a historical site, though not opened to the public.

The uniforms, documents, and personal effects have been transferred to the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, where they are available to researchers.

The property purchased by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture, will be maintained as a memorial to the complex legacies of World War II, not celebrating escape, but documenting it as part of the complete historical record.

One question remains genuinely open.

Did Friedrich von Walstein die peacefully in Buenus Aries or Sa Paulo? decades after the war that supposedly killed him.

His weremok past successfully buried beneath a comfortable exile or does he rest in an anonymous grave somewhere else? His final identity as mysterious as his escape.

The Alpine Chamber offered answers, but it also presented new questions.

A reminder that even 79 years later, the war’s final chapters continue to be written.

News

End of content

No more pages to load