Nineteen Cents

Savannah in 1849 wore its cruelty like perfume.

Sweet at a distance, rancid when you breathed it in.

The streets were paved with coin-bright respectability, and underneath that gilded veneer lay a rot organized like a ledger.

Morning fog parted over the auction block, the way curtains part before a performance nobody asked to watch.

People gathered with the appetite of candle flames, their heat clean, their purpose indecent.

The city believed itself civilized because it kept careful records.

The city believed itself blessed because it could pray without speaking the names of those it destroyed.

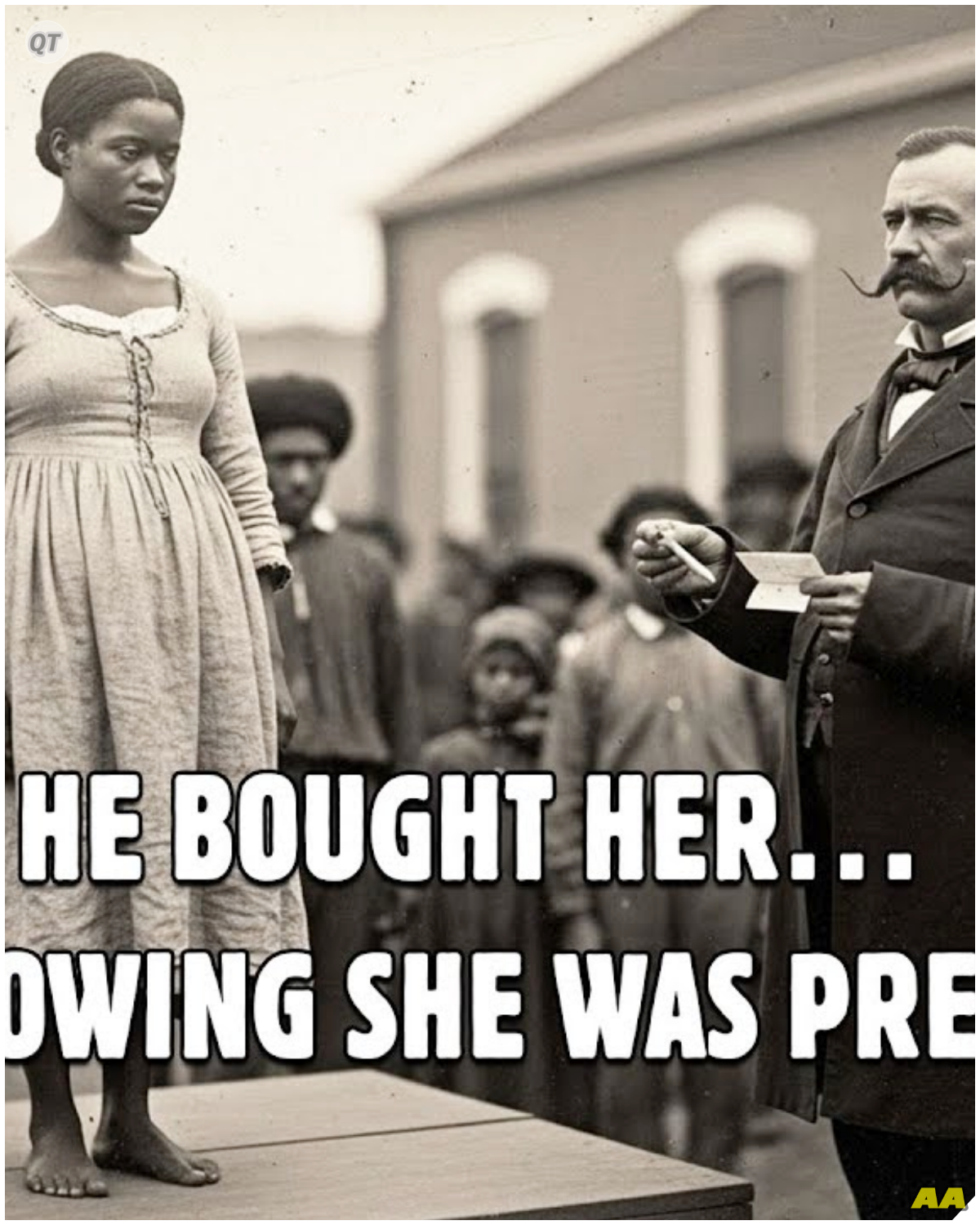

Dinah stood on the platform where human lives were pronounced in numbers.

She was pregnant, body bent into a private crescent around the gravity of another heartbeat, a silhouette that carried two futures at once and knew neither would be allowed to name themselves.

Her hands were folded the way you fold a letter you cannot afford to send.

Men examined her the way men examine investments.

They speculated on her endurance, like farmers speculating on weather with maps drawn by trembling.

Her price was chalked up on a board by a clerk whose handwriting had learned how to mutilate without bleeding.

Nineteen cents.

Not nineteenth dollars, not a number that could pretend to be fair.

Nineteen cents, less than a pound of coffee, less than the cost of the sugar to sweeten that coffee.

A price designed to humiliate, to hand her over to a particular cruelty as if she were the discarded skin of a fruit.

The crowd murmured, uneasy at the arithmetic but not at the morality.

Dinah’s previous owner had sent her to be purchased by the plantation master who haunted this city’s nightmares and never appeared in its prayers.

He collected pregnant women the way a storm collects roofs.

He did not leave survivors.

He had discovered a loophole in the legal mesh and crawled through it with patience.

Nineteen cents.

The auctioneer’s gavel tapped like a small, polite murder.

The plantation master’s name drifted through the crowd like smoke, wearing pseudonyms to avoid indictment.

He was known for a cellar so quiet even cockroaches refused to speak there.

He bought women carrying children, and the clock, which had learned to be merciless, scheduled them for never.

He had crafted a system where the law smiled and the ledgers thanked him.

The auction house had become a theater where justice was set dressing, and the villain always remembered his lines.

Dinah stared forward as if the horizon had agreed to hold her gaze without blinking.

Her belly pushed against the ragged dress like a lantern under cloth.

behind her ribs lived a music she refused to apologize for.

The auctioneer Étienne Delacroix, whose penmanship could make a lie traceable, did his job.

He did not look her in the eye.

He turned the mechanics of her sale with hands that had learned that truth can be documented without being respected.

He read numbers, and numbers read him back, and neither changed shape.

The master raised his hand.

The crowd’s hunger tightened.

The gavel rose.

A voice interrupted.

It was not loud.

It was accurate.

The man who spoke was ordinary in the way a key looks ordinary until used.

He wore a coat that pretended to have nothing to say.

He stood near the edge of the platform where the shadows keep their bargains with light.

His eyes were not brave.

They were necessary.

He announced a bid that sounded absurd until it became the only sound anyone could hear.

Twelve hundred dollars.

The air learned the shape of amazement.

Men in hats turned as one mechanism.

Women pressed gloved hands to mouths as if their silence might be mistaken for permission.

A child laughed once and was slapped gently by a mother whose tenderness had been taught to behave.

The master blinked.

He lifted his hand again to mock, to posture, to remind arithmetic who owned it.

The bidder did not move.

The auctioneer read the number a second time, and it became an instrument.

Twelve hundred dollars.

The crowd shifted, as a flock shifts when the sky changes mood.

The gavel fell.

The bid held.

The master lowered his hand, and hatred sat down with an etiquette it did not deserve.

They say three strangers pooled their money in the night.

They say one was a dockworker whose palms had turned so often toward the sea that their lines had learned how to carry secrets.

They say another was a seamstress whose needle had stitched freedom into the hems of dresses she would never wear.

They say the third was a teacher who knew words as weapons and decided to use them as ladders.

They were not abolitionist heroes in the theatrical sense.

They were quiet, ordinary, precise.

They had learned the pattern of evil, and they decided to improvise justice without asking permission.

They walked into that auction armed with currency and conviction and the kind of courage that doesn’t bloom for applause.

Dinah descended the platform with the posture of someone carrying a house on her back and refusing to let the door swing open.

The strangers did not touch her until she permitted touch.

The master watched with the eyes of a farm that had just been told rain was under new management.

The crowd pretended to discuss trade winds.

The city pretended it had witnessed a purchase like any other.

The strangers took Dinah not home but below.

Down a flight of stairs that smelled like salt and wood and a kind of honesty that only darkness can admit.

The dockworker led, his breath a metronome, his heart a drum.

The teacher whispered instructions to nobody because the air itself needed to learn.

The seamstress carried a parcel that contained more rope than hope and a knife as small as a sentence.

They packed Dinah into the belly of a ship like a secret the ocean promised to keep.

The captain did not ask questions.

He poured whiskey over his conscience and decided to pretend his eyes had never learned to focus.

The cargo hold was a school for patience.

Seven days of silence fed by whispers, seven days of a pregnancy held like a burning lamp at the center of a dark city refusing to perform panic.

Dinah lay among barrels and crates labeled in languages that did not know her name.

Her breath counted minutes.

The strangers brought water and bread and the kindness of presence, which is the only kindness that does not require explanation.

Dinah dreamed of a field where no one counted her steps.

She woke to the sound of rope learning to hold its breath.

Above, the city turned its rumor mill.

The master raged with restraint, the way a man rages when he has taught himself how to translate anger into litigation.

He demanded records, and records bowed but did not apologize.

The auctioneer wrote, and writing became a court he did not deserve to preside over.

The law smiled.

The law told the master to be patient.

The law did not say what it intended to do with the word human.

Dinah survived the voyage.

Survival is sometimes a small thing, sometimes a revolution.

She reached a city that did not know her but did not intend to kill her immediately.

Freedom does not arrive with trumpets when the enemy is bureaucracy.

The Underground Railroad received her not as a miracle but as a responsibility.

If you pressed your ear to her ribcage, you could hear gratitude argue with grief and both agree to work side by side.

Dinah found shelter with people who spelled protection without boasting about it.

The seamstress mended her dress with thread that had seen more action than most soldiers.

The teacher taught her letters with patience and refused to hurry genius.

The dockworker went back to the river and listened.

Listening is a profession when the water carries memory.

Back in Georgia, time kept doing its job with awful discipline.

December became a warehouse and January an arithmetic problem.

The plantations continued their worship of sugar and inventory.

The master purchased other women and turned them into nothing the law recognized as horror.

He built a cellar under the floor of his house like an extra mouth that insisted on eating pain.

He interred bodies in rooms that had never been taught the virtue of light.

He carried the taste of murder around the property like a hymn he admired for its harmony.

The city continued its routine of prayer without confession.

Then the war came.

Union soldiers turned the soil.

They entered houses wearing the kind of authority that comes from orders and ends in guilt.

An officer with a face carved by marching and a heart refusing to be carved by anything entered the plantation master’s house and felt a weight he could not lift with rank.

The cellar was concealed the way a villain conceals laughter.

He found the door.

He found the staircase.

He found the silence that had eaten human voices and pretended to be a floor.

Eight women.

Their infants.

Bones arranged into a mathematics that screamed without sound.

The room’s air smelled like a failure so profound it wanted to change species.

The officer took off his hat because respect is sometimes the only available instrument in the orchestra.

The soldiers backed away the way men back away from a truth that corrects posture without permission.

The cellar became a courtroom where history was the judge and none of the attorneys dared to speak.

They documented.

Carefully.

They did not know what else to do.

Photographs are a negotiation between light and memory, and light refuses to negotiate when asked to expose atrocity.

The records were written by men who understood that words are a fragile bottle for a storm.

They closed the cellar.

They sealed the door.

They burned the name of the master and locked the ashes behind policy.

The official reasoning was propriety.

The unofficial reasoning was a fear that America would not survive its own mirror.

Years passed.

Official history grew like ivy over stone, pretty and hungry.

Dinah’s life became anonymous in a way that made anonymity feel like a strategy.

She bore her child, who arrived with the resilience of a river stone.

She worked, mind and hands, at jobs that did not require her to kneel before anyone but the truth.

Her body taught her the art of continuance.

She refused to be grateful in a way that felt performative; instead, she practiced gratitude like a craft, polishing it in private, never displaying it like a trophy to make others comfortable.

Her child grew with a gaze that could untie knots in other people’s voices.

The seamstress taught him stitches dense enough to hold a wound in place until love learned how to do its job.

The teacher taught him how to turn sorrow into syntax and not let syntax confess to vanity.

The dockworker showed him how rivers hold countries together and how countries do their best to ignore the river until it floods and demands pronouncement.

They formed a small republic in a single house.

Its constitution was written in meals eaten without fear and stories told without audit.

Decades later, 1931 arrived dressed as a question and carrying a key.

Georgia remembered the cellar the way a drunk remembers a debt.

Authorities dismantled the door with hands trained in hesitation.

They entered like men entering an old church with an untested faith.

The air had petrified.

The photographs they took were sealed almost immediately, wrapped in an inhuman shyness that pretended to be policy.

The evidence was so disturbing that officials forbade public discussion for the kind of decades that turn into a custom.

Silence became a city ordinance.

Memory became contraband.

Under the fluorescent blinking truth of modernity, Dinah’s grandson found the rumor.

He worked at a library where newspapers behaved like fossils with opinions.

He found a footnote so precise it became a summons.

He traveled to the plantation.

He stared at the ground like a man reading a map written in sorrow.

He placed his ear on the earth, and the earth performed a low ceremony in response.

He asked for permission to see the sealed evidence.

Permission did what permission does when asked to perform justice.

It refused.

So he went to the river.

He stood where the water had carried his grandmother’s fear like a suitcase and delivered it to a city where survival had purchased a new name.

He spoke to the water.

Not loudly.

Accurately.

He told it that a price can be an instrument of murder.

He told it that a woman had been valued at nineteen cents and rescued with twelve hundred dollars.

He told it that arithmetic had been used to kill and then used to save, and neither absolved anyone, and both demanded acknowledgment.

The river lifted itself slightly like a listener making room inside its attention.

The grandson decided to build what authority would not build.

There are memorials that stand on columns and shout their names.

There are memorials that sit on benches and refuse to leave.

He fashioned a small shrine at the river’s edge.

No statues.

No bronze.

A circle of stones.

Eight large ones, many small.

He placed a jar of salt in the center because salt remembers flesh.

He scratched one sentence into the dirt with a stick the size of a pencil.

He did not write the master’s name.

He wrote a number.

Nineteen.

He wrote another number.

Twelve hundred.

He waited.

People came, the way people come to places that tell the truth without trying to win.

A woman wept and did not apologize.

A man took off his hat without being told by signage.

A child counted the stones and learned subtraction as reverence.

Some visitors were academics with coats that smelled like conferences.

Some were tourists with cameras unused to humility.

Some were neighbors whose lineage had twisted around this city like jasmine and refused to be pruned.

They stood in a circle and practiced a ritual the water had taught them: listen, breathe, name, vow.

The archives remained sealed for a time that felt like a wound refusing clean stitches.

The governor explained nothing.

The legislature explained policy.

The sheriff explained inconvenience.

Explanations are a kind of furniture that crowds a room until movement becomes impossible.

The shrine did not care.

It was not a lobbyist.

It was not a press conference.

It was not a bill.

It was a sentence.

Under that sentence grew a community with its own clock.

Each year, on the date the auction had tried to perform humiliation as law, they gathered at dawn.

They brought coffee and refused to sweeten it.

They told the story of a woman valued at nineteen cents less than a pound of that very commodity, whose life had been repositioned by strangers wielding currency like choreography.

They spoke the words with a care that made each syllable feel like a washed stone.

The ritual became a local weather.

The river learned when to be quiet.

The wind kept its hands to itself.

I wish the master had been dragged into a courtroom that knew the word mercy as well as it knew the word verdict.

I wish the cellar had been transformed into a chapel and the chapel taught the city how to pray for the right things.

I wish the authorities had not sealed horror behind a door labeled do not disturb for fear of disturbing their own sleep.

Wishes are maps for places that cannot be reached by walking.

Wishes are also work orders.

The community worked.

They lobbied.

They wrote.

They testified.

They performed stubbornness.

Finally, a crack in policy appeared like a vein returning blood to an extremity.

The evidence was unsealed, the photographs allowed to behave like proof.

They saw the bones.

They saw the small skulls.

They did not look away.

Looking away is an offense in the presence of the dead.

They built a memorial on land that had practiced forgetting as a form of religion.

They planted trees that insist on naming seasons without asking permission.

Dinah did not live to see this.

She had died the way ordinary heroes die: tired, prepared, folded into a family that forbade her life to be measured by one number.

Her son spoke at the dedication the way a river speaks at dawn.

Her grandson placed the jar of salt at the base of the central stone.

People held hands not because photographs demand choreography but because grief demands architecture.

The city, which had fashioned its myth over centuries of polite cruelty, tilted slightly toward honesty.

The memorial is not large.

The memorial is right-sized for an enormous truth.

Some nights, the moon sits there as if it were a witness called to testify about light’s complicity and light’s courage.

Some days, children run their fingers along the engraved names and learn that spine equals spelling.

The inscription avoids adjectives like brave and tragic because adjectives are a form of vanity.

It uses nouns.

Mother.

Child.

Cellar.

Auction.

Law.

Rescue.

River.

It adds numbers: eight, nineteen, twelve hundred, seven.

It refuses to translate them into poetry because poetry, like policy, can be tempted to decorate.

What does a price mean when attached to a person.

It means law began with a failure and made a career of it.

It means ledgers were instruments that played a music composed by harm.

It means auditors were decorations on a machine designed to grind.

It means the world built rooms where compassion was considered an intrusion.

It means that a number can be a weapon.

It means arithmetic can be violent.

What does rescue mean when purchased.

It means that mercy learned a dialect it hated and spoke it anyway.

It means the world is ridiculous and sometimes that ridiculousness can be harnessed to prevent a disaster.

It means good is often forced to walk through a gate built by evil to enter a yard where instructions do not fit a human body.

It means survival is a form of protest.

It means that strangers can become angels disguised as accountants.

Dinah’s story is a mirror held up to a nation that loves spectacle and hates stillness.

It offers no special effects.

It offers ten thousand small adjustments to posture.

It asks you to examine the way you use numbers.

It asks you to remember that a system is nothing without habits and habits are nothing without choices.

It asks you to choose and then be prosecuted by those choices until you choose again and better.

It asks you to stand at the river and pronounce the names of those you have never met with the fearlessness of a candle that knows darkness is lazy.

The discovery of the cellar by Union soldiers was a scream that history declined to hear.

Our ears have matured since 1863.

If they have not, we must force them.

If we do not honor the victims of slavery, we practice a politics of erasure that will not end with the past.

It will eat the present and lightly season the future.

Honor is not a plaque.

Honor is insisting that the word human is not negotiable.

Honor is paying attention to the arithmetic used by winners.

Honor is refusing to let sealed records behave like tombs with locks.

Honor is making a shrine without stalling for permission and then inviting permission to sit down and take notes.

A century and more after nineteen cents tried to write a sentence, the city finally wrote back.

It wrote in stone and in silence and in gatherings that refused to perform entertainment.

The people came.

They learned to listen to ground.

They learned that the soil carries more history than textbooks, and the river edits better than committees.

They learned that the Underground Railroad was not a myth but a thousand small rooms where ordinary people performed surgery on history with kitchen tools.

They learned that the cellar’s silence had been a policy and that policy can be overruled by ritual.

Dinah’s grandson still visits the shrine.

He brings coffee without sugar.

He places nineteen pennies around the jar of salt.

He lights a candle.

He does not speak.

He waits until the sun arranges itself.

He practices humility.

He returns home.

On the mantle above his stove sits a photograph of a woman who taught him to count breath like currency and spend it wisely.

He does not call her victim.

He calls her ancestor.

Savannah wears a new perfume now.

It smells like magnolia and salt and the old, metallic tang of shame forced out through pores.

It smells like river and paper and the ink of signatures that mean something honest.

It smells like sweat that belongs to people who build and refuse to destroy.

It smells like a city trying to learn the difference between memory and nostalgia.

It smells like a question.

Has enough been done to honor the victims of slavery.

No.

Enough does not exist as a quantity because there is no ledger for grief.

Enough is a direction.

Enough is a discipline.

Enough is a refusal to allow policy to translate horror into footnote.

Enough is a life lived with the tutorial of a shrine intact.

Enough is a school where children read arithmetic alongside ethics and learn to recognize nineteen cents as a poison that must never be ingested again.

Enough is a river kept clean of the logic that once used it to ferry despair.

Enough is a refusal to let sealed rooms remain sealed.

Enough is opening the door every morning and asking the air if it is ready to tell the truth.

Dinah’s price was nineteen cents.

Dinah’s rescue was twelve hundred dollars.

Dinah’s voyage was seven days in a darkness that agreed to carry her.

Dinah’s hidden predator was a cellar that had trained silence to be obedient.

Dinah’s descendants are a shrine where arithmetic bows to mercy.

The plantation master is a rumor that accomplished nothing eternal.

The auction house is a ghost that teaches ledgers to blush.

The city is a student.

The nation is a jury.

The river is a teacher.

Nineteen cents.

If you say it slowly, you can hear a coin drop into a hole.

Twelve hundred dollars.

If you say it slowly, you can hear strangers collectively reshaping the mechanics of a cruel performance.

Seven days.

If you say it slowly, you can hear a heartbeat.

Eight women and their infants.

If you say it slowly, you can hear a choir and then an ache and then an oath.

At dusk, the shrine glows as if the stones remember how light behaves when asked not to be decorative.

People stand.

They do not clap.

They do not take.

They do not conquer.

They convene.

They practice.

They promise.

They go home altered.

The city breathes.

The river listens.

The ledger closes itself and waits for morning without fear.

This is not a happy ending.

It is an honorable continuation.

The horror was legal.

The rescue was illegal in spirit and moral in practice.

The prison was a cellar.

The escape was a ship’s belly.

The memorial is a circle of stones.

The question is a compass.

The answer is work.

If the future ever asks us for proof, we must bring the shrine and the salt and the pennies and the photograph and the story and the silence and the vow.

We must stand at the river and hold the numbers until they melt in the hand.

We must say the word human with a voice that does not stutter.

We must decline to forget.

Nineteen cents did not win.

The cellar did not win.

The law did not win.

The master did not win.

Dinah lived.

Her child lived.

The community learned.

The river taught.

The shrine exists.

The door is open.

The past continues to demand attention.

The present continues to offer it.

The future continues to take notes.

And somewhere, on an invisible auction platform that exists in the minds of those who still think people are prices, a gavel refuses to fall.

News

“Boxing’s Biggest Event: Mayweather and Pacquiao Rematch for $600 Million in 2026!” -ZZ After years of speculation and anticipation, boxing icons Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao have officially confirmed their rematch, scheduled for September 2026, with a jaw-dropping $600 million on the line. This epic showdown is expected to reignite the fierce rivalry that captivated fans worldwide. What led to this long-awaited rematch, and how will both fighters prepare for this historic event? Get ready for an in-depth analysis of what this fight means for the future of boxing!

The $600 Million Showdown: Mayweather vs.Pacquiao II – A Clash of Titans In the arena of boxing, where legends are…

“Confessions of a Fan: My Love-Hate Relationship with Dana White!” -ZZ In an honest and candid reflection, I share my tumultuous journey with UFC President Dana White. Once filled with disdain for his controversial decisions and brash personality, I find myself wrestling with those feelings once again. What led to this complicated relationship, and how has my perception of White evolved over time? Join me as I explore the complexities of fandom and the impact of a polarizing figure in the world of mixed martial arts.

The Fall of a Titan: Dana White’s Controversial Maneuvers in the Fight World In the tumultuous realm of mixed martial…

“Browns Make Headlines: Todd Monken Releases Dillon Gabriel—What’s Next?” -ZZ In a stunning development, the Cleveland Browns have decided to part ways with quarterback Dillon Gabriel, as confirmed by offensive coordinator Todd Monken. This unexpected release raises questions about the team’s strategy moving forward and Gabriel’s next steps in his career. What prompted this decision, and how will it affect the Browns’ quarterback situation? Get ready for an in-depth analysis of this significant move in the NFL.

The Shocking Release: Todd Monken and the Fallout of Dillon Gabriel’s Departure In the high-stakes world of the NFL, where…

“Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford WEIGH IN: ‘There to be HIT!’ After Ryan Garcia’s Victory!” -ZZ In a thrilling post-fight analysis, boxing stars Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford shared their candid reactions to Ryan Garcia’s latest win. Highlighting the dynamics of the fight, they emphasized the opportunities and vulnerabilities that emerged in Garcia’s performance. What insights did these champions provide about Garcia’s style, and how might this impact future matchups in the boxing world? Join us as we break down their reactions and what they mean for the future of the sport.

The Aftermath of Glory: Shakur Stevenson and Terence Crawford React to Ryan Garcia’s Stunning Victory In the electrifying world of…

“Stefon Diggs: The Star Who Can’t Escape Controversy—What’s Really Going On?” -ZZ Despite his remarkable skills and contributions to the Buffalo Bills, Stefon Diggs finds himself entangled in controversy that he just can’t shake. From social media outbursts to strained relationships with teammates, the narratives surrounding him continue to evolve. What are the reasons behind his ongoing struggles to find peace and stability, and how will this affect his future in the NFL? Join us as we explore the intricate web of challenges facing Diggs.

The Unraveling of Stefon Diggs: A Star Caught in the Shadows In the dazzling world of the NFL, where talent…

“BREAKING: Shedeur Sanders’ Image Takes a Hit After Fernando Mendoza’s Controversial Call!” -ZZ In a dramatic turn of events, the carefully crafted narrative around Shedeur Sanders has taken a significant hit following Fernando Mendoza’s decision. As the college football world reacts to this unexpected twist, the implications for Sanders and his team’s future are becoming clearer. What does this mean for the young quarterback’s reputation, and how will it shape the upcoming season? Prepare for an in-depth look at the fallout from this shocking development!

The Fall of a Star: Shedeur Sanders’ Narrative Shattered by the Mendoza Decision In the world of college football, where…

End of content

No more pages to load