October 29th, 2019, Dubai.

The penthouse sits 43 floors above the marina, suspended in a space where the city’s noise cannot reach.

Floor toeiling windows frame the Palm Jira like a postcard that never changes.

Inside, the air conditioning hums at exactly 22° C.

Marble floors stretch in every direction, polished to a mirror finish that reflects the recessed lighting overhead.

Everything in this space has been chosen, positioned, calibrated.

Nothing is accidental.

On that marble floor, near the base of a leather sofa that costs more than most people earn in a year, Dr.

Samir Hassan lies convulsing.

His body jerks in ways bodies are not meant to move.

Foam gathers at the corners of his mouth.

His eyes are wide, searching, finding nothing that can help him.

The sounds he makes are not words.

They are the noises that come before silence.

Standing over him is Celestina Santos, 28 years old, 5’3, wearing a cotton night gown she bought at Carfor 3 weeks ago.

Her hair is pulled back in a loose ponytail.

No makeup, bare feet on cold marble.

In her hand, she holds his phone.

The screen is recording.

You wanted to watch me break.

she says.

Her voice is steady, clinical, empty of everything except observation.

Now it’s your turn.

She does not move closer.

She does not call for help.

She simply stands there documenting the way he documented her.

Around the room, hidden in smoke detectors and air vents and the corners of picture frames.

Cameras are recording this moment, too.

But those cameras belong to him.

This phone right now belongs to her.

The convulsions slow.

His breathing becomes shallow, irregular, wrong.

She recognizes the pattern.

She has seen it before in hospital beds, in ICU rooms where families gather and machines make their steady mechanical sounds.

This is what the end looks like when it comes from the inside.

When it stops, when his chest no longer rises, she stops recording, deletes the video, wipes the phone with the edge of her night gown, places it carefully back into his pocket.

Then she sits down on the sofa above his body and waits exactly 3 minutes.

A nurse knows how long it takes for a brain to die without oxygen.

She counts the seconds in her head the way she used to count them during compressions in emergency situations.

1,000 2,000 300.

At 180, she picks up her own phone and dials emergency services.

When she speaks, her voice cracks in exactly the right places.

But to understand how a woman ends up standing over a dying man with a phone in her hand and nothing in her eyes, we have to go back.

Not two weeks, not two months.

We go back to a different city, a different country, a different version of who Celestina Santos used to be.

Manila, 1991.

Celestina is born in a public hospital in Quesan City on a Tuesday morning when the heat is already pressing against the windows.

Her mother, Teresa, is a school teacher.

Her father, Rodrigo, operates a machine in a textile factory.

They live in a two-bedroom apartment in a building where the walls are thin enough that you can hear your neighbors arguments, their television programs, their lives.

The apartment holds six people.

Rodrigo and Teresa in one bedroom, Celestina and her two sisters in the other.

Her older brother sleeps in the living room on a foldout mat that gets put away each morning.

There is one bathroom, one small kitchen with a stove that only works on three of its four burners.

A window unit air conditioner that they turn on only during the worst heat, only for a few hours at a time.

Because electricity costs money, and money is something that must be carefully measured, carefully spent, carefully mourned when it is gone.

From the earliest age Celestina can remember, money is the background noise of every conversation in that apartment.

Not the presence of it, but the absence.

The constant mathematics of survival.

Rent is due on the 1st.

The water bill comes midmon.

School fees are collected at the start of each semester.

And every time that collection happens, her parents’ voices get quieter, tighter until the payment is made, and the tension releases for a few weeks.

She watches her mother wake up at 5 in the morning to prepare lessons and grade papers before the family wakes.

She watches her father come home with exhaustion in his shoulders, sitting at the small kitchen table with a beer.

He allows himself once a week, staring at nothing.

She watches her older siblings navigate the same narrow hallways, the same limited choices, the same unspoken understanding that wanting more is not the same as getting it.

At school, the differences are visible in ways that children notice but do not yet have language to describe.

Some classmates arrive in cars with drivers.

Some have backpacks that still have tags on them, shoes that are not handme-downs, lunch boxes with food their parents did not have to plan 3 days in advance.

Celestina has none of these things.

What she has is good grades, perfect attendance.

A teacher who tells her mother during a parent conference that Celestina is the smartest student in the class, and maybe if they are careful, if they plan, she could be the one who goes further.

That night, Teresa and Rodrigo sit at the kitchen table after the children are asleep.

Celestina is 12, pressed against the wall in the hallway, listening.

She hears her mother say the word scholarship.

She hears her father say the word sacrifice.

She hears them talk about nursing, about overseas work, about salaries that are three times, five times, 10 times what they make in Manila.

She hears her mother cry quietly.

The kind of crying that is not about sadness, but about hope that feels too big to hold.

From that night forward, Celestina understands what her life is supposed to be, not her choice, not her dream, her assignment.

She studies with the kind of focus that other teenagers reserve for things they love.

She does not love biology or anatomy or pharmarmacology.

She simply knows that these subjects are the pathway out.

In high school, while her classmates talk about boys and movies and weekend plans, Celestina is in the library.

She memorizes bone structures.

She learns drug interactions.

She teaches herself medical terminology in English because the nursing board exams are in English and passing them is not optional.

In 2013, at 22 years old, Celestina takes the nursing board exam.

3 days of testing when the results are posted online 6 weeks later, she is at an internet cafe with five other nursing graduates, all of them crowding around a single monitor.

Santos, Celestina Marie, registered nurse.

rating 87.

4% top 5% nationally.

She walks home in a days.

Her mother cries and thanks God.

Her father opens a beer even though it is a Tuesday.

But what Celestina feels in that moment is not joy.

It is relief.

She has done what she was supposed to do.

She has not failed.

The job at Manila General Hospital starts 2 months later.

The ICU 12-hour shifts, sometimes longer.

The work is brutal in ways nursing school only hinted at.

Patients who code in the middle of the night.

Families who scream or beg or shut down completely.

Doctors who bark orders and expect them followed without question.

Celestina is good at it.

She is fast with IVs.

She catches medication errors before they happen.

She stays calm during emergencies when other nurses freeze.

But the pay is exactly what she expected, small.

She sends 70% of it home each month.

What remains covers her shared housing with three other nurses, her food, her commute.

There is no money left over for anything that is not essential.

At night, after shifts that leave her too tired to think, she lies in her narrow bed in a room she shares with two other women and looks at her phone.

Social media shows her glimpses of a world that exists somewhere else.

Friends from high school who married well, who post photos of vacations and restaurants.

Former classmates who moved to the Middle East or America, who send money home in amounts that make her monthly contribution look like pocket change.

In 2015, one of her roommates comes home with news.

A hospital in Dubai is recruiting Filipino nurses.

The salary is triple what they make at Manila General.

Housing is provided.

Contracts are 2 years minimum.

Celestina goes to the interview on her day off.

Three weeks later, the email arrives.

Offer of employment, Royal Emirates Medical Center.

ICU position.

Salary 12,000 dams per month.

Start date March 2016.

She accepts before she has fully processed what it means that she will leave her family that she will live in a country where she does not speak the language, does not know the customs, will be replaceable in ways she has never been replaceable before.

On the day she leaves, March 8th, 2016, the whole family comes to the airport.

They stand in the departures hall holding each other, saying things that do not need to be said.

Her mother presses a rosary into her hand.

Her father tells her to be careful.

Celestina does not have an answer when her youngest sister asks when she will come home.

Dubai, March 2016.

The heat is the first thing.

She steps off the plane into air that feels like opening an oven.

The airport is enormous.

Glass and steel and moving walkways that stretch longer than city blocks.

Advertisements in Arabic and English for watches and perfumes and cars that cost more than her family’s apartment.

A hospital representative meets her at arrivals.

He leads her to a van where six other Filipino nurses are already waiting.

They drive through a city that does not look real.

Buildings so tall they disappear into haze.

Construction cranes everywhere.

Cars that she has only seen in movies.

The staff housing is in a neighborhood called Satwa.

Older buildings lower rent far from the tourist areas.

The apartment is clean, small.

She has her own room for the first time since she was a child.

It has a bed, a desk, a window that looks out over other apartment buildings.

There is a small kitchen shared with three other nurses.

One bathroom, air conditioning that works.

That night, alone in her room, Celestina sits on the edge of the bed and tries to feel something other than exhausted.

This is supposed to be the beginning, the better life.

But all she feels is the weight of how far she is from anything familiar.

The work starts 2 days later.

Royal Emirates Medical Center is a private hospital that serves Dubai’s wealthy residents and medical tourists.

Everything is new.

The equipment is state-of-the-art.

The rooms are private, spacious, designed to look less like hospital rooms and more like hotel suites.

Celestina is assigned to the ICU.

Her supervisor is a British nurse named Margaret who has been in Dubai for eight years.

Margaret gives her the orientation in clipped, efficient sentences.

The patients here expect a certain standard.

Families can be demanding.

Doctors have little patience for mistakes.

Work hard.

Keep your head down.

Do not get involved in drama.

The other nurses are a mix.

Filipinos, Indians, Jordanians, a few Westerners.

Everyone is professional.

Everyone is polite.

But there is a hierarchy that is never spoken but always present.

Western nurses are paid more for the same work.

Arab nurses are treated with more respect by Arab families.

Filipino nurses are seen as reliable, hardworking, and ultimately replaceable.

Celestina learns the rhythm quickly.

12-hour shifts that sometimes stretch to 14.

Patients on ventilators, patients recovering from cardiac surgery, patients who coded in the middle of the night and are being kept alive by machines and medications.

She moves between rooms with practice deficiency, checks vitals, adjusts drips, documents everything in perfect English.

She sends money home at the end of her first month, more than her parents make combined.

Her mother calls her crying, thanking her, telling her how proud they are.

Celestina sits in her small room after the call ends and feels nothing.

No pride, no satisfaction, just the same mathematics.

She has done what she was supposed to do.

The months pass in a kind of blur.

Work, sleep, eat, repeat.

She goes to church on Fridays with other Filipino nurses.

She goes to the mall occasionally, walks through stores she cannot afford, buys nothing.

She is lonely in a way she has never been lonely before.

In Manila, she was poor but surrounded.

Here, she has her own room, but no one who knows her.

The other nurses are kind, but temporary.

Everyone is passing through, counting down contracts, saving for futures somewhere else.

By 2017, she has been in Dubai for a year.

Her savings account has a number in it that would have seemed impossible 2 years ago.

Her family has repaired their apartment, bought new furniture, enrolled her youngest sister in a better school.

The mathematics of her life have improved for everyone except her.

She video calls home every Sunday.

Her mother’s face on the small screen.

her father in the background, her siblings crowding in to say hello.

They tell her about their weeks, their small dramas.

They ask her about Dubai.

She tells them about the weather and the hospital and the other nurses.

She does not tell them that she spends most of her time alone, that she has not made a real friend.

That some nights she lies in bed and wonders if this was worth it.

In March 2018, two years into her contract, something shifts.

Not in her circumstances, but in her awareness of them.

She watches a wealthy Emirati family in the ICU, gathered around a grandmother who is dying.

They are loud in their grief, demanding in their requests, but also clearly bound to each other in ways that money cannot buy or replace.

When the grandmother passes, they hold each other and cry and stay in the room for hours.

Celestina watches from the doorway and realizes that she has no one who would hold her like that.

If something happened to her here, her family would mourn from thousands of miles away.

Her colleagues would be sad for a day and then move on.

She would be replaced within a week.

That realization sits with her for days, not as sadness, but as a kind of hollow recognition.

She has built financial stability for people she loves, but she has built nothing for herself.

No relationships, no life, just work and sleep and the same careful mathematics that keep her functional but not alive.

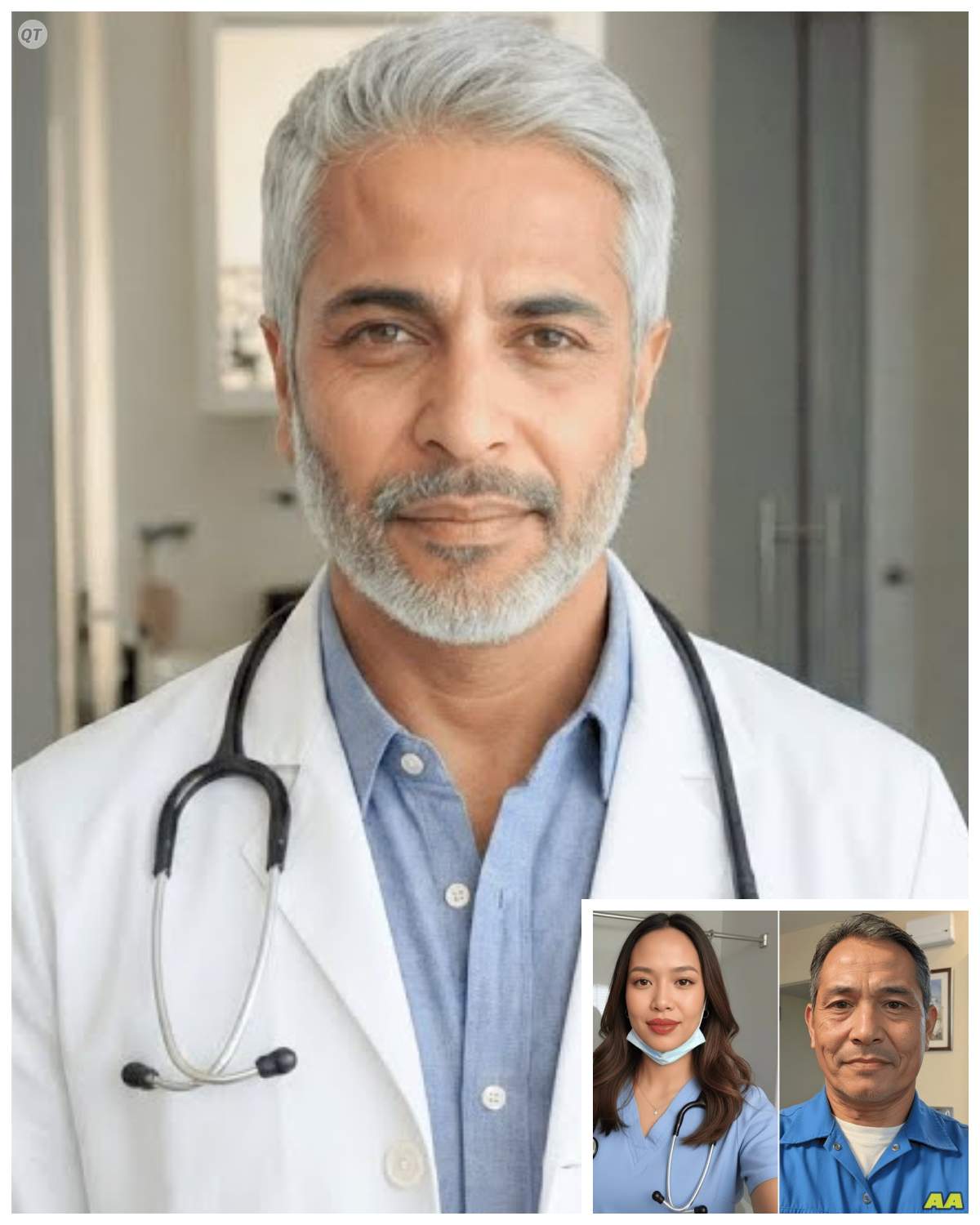

It is in this state, quiet and isolated and invisibly desperate, that she first notices Dr.

Samir Hassan, not because he is kind, not because he is different from the other surgeons who move through the ICU with authority and impatience.

She notices him because one morning in April during a routine procedure, he hands her an instrument and says, “Excellent work, nurse Santos.

” It is the first time in 2 years that anyone has said her name with something that sounds like respect.

Dr.

Samir Hassan is 35 years old in the spring of 2018.

And to anyone who knows him casually, his life looks exactly the way a successful life is supposed to look in a city like Dubai.

He drives a Porsche Cayenne.

He lives in a penthouse in the Marina district with a view that real estate agents use in brochures.

He wears watches that cost more than most people’s annual salary and suits customade by a tailor in London.

His professional reputation is flawless.

Cardiovascular surgeon trained at Imperial College London and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

published researcher sought after by private patients who fly in from across the Gulf specifically to have him open their chests and repair what is broken inside.

In the operating room, his hands are steady, his decisions quick, his outcomes consistently excellent.

Socially, he moves through Dubai’s upper circles with practiced ease.

Friday brunches at five-star hotels, yacht parties in the marina, VIP tables at nightclubs where bottle service costs what some families spend on rent.

He is charming in the particular way that very attractive, very wealthy men can afford to be.

He listens when people talk.

He remembers details.

He makes everyone he speaks to feel like the most interesting person in the room.

Women notice him everywhere he goes.

Some are bold enough to approach.

Others simply watch and hope he will notice them.

He dates casually, frequently, and always with a clear boundary that is never explicitly stated, but always understood.

No expectations, no long-term plans.

What people do not see because he is careful never to let them see is the mechanism underneath.

The part of him that operates like a piece of precision equipment designed for a single function control.

Samir was born into money in 1983.

The second son of a real estate developer whose name appears on buildings across Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

His childhood was private schools and international vacations and a kind of wealth that insulates you from ever experiencing real consequence.

His older brother was groomed to take over the family business.

Samir, the spare, was encouraged to pursue whatever interested him as long as it reflected well on the family name.

He chose medicine not out of calling or compassion, but because it offered something his family’s money could not.

Authority over life and death.

a role where people looked at him not because of who his father was but because of what he could do with his hands.

In university he was brilliant top marks photographic memory but even then classmates noticed something slightly off.

He was charming but never warm.

He helped study groups but only when it served him.

He dated women who were attractive and intelligent and every single one of them ended the relationship with a variation of the same story.

That he made them feel special until he did not.

That he listened until he stopped.

That there was something in his eyes when he looked at them that did not match the words coming out of his mouth.

One girlfriend during his final year at Imperial College had what she later described to friends as a breakdown.

She stopped attending classes.

She stopped eating.

When she finally left London and returned to her family in Jordan, she told them only that she could not be around him anymore.

Samir, when asked about it by mutual friends, said she had always been unstable, that he had tried to help but could not save someone who did not want to be saved.

His version of events was delivered with just enough concern, just enough sadness that people believed him.

There was another woman during his residency in Boston, a Lebanese medical student named Amamira who he dated for nearly a year.

They talked about marriage.

Two weeks before the wedding, she called it off.

No explanation given publicly.

Privately, she told her family that she could not marry him, that she did not feel safe.

Amira returned to Beirut.

Samira returned to Dubai.

When people asked what happened, he said she had gotten cold feet, that he had dodged a bullet.

By the time he reaches 35, the pattern has repeated enough times that a very careful observer might notice it.

Women enter his life.

They are drawn by his charm, his looks, his success.

For a while, everything is perfect.

Then something shifts.

The woman begins to change.

She becomes anxious, withdrawn.

She starts to question herself in ways she never did before.

And then eventually she leaves or she has a breakdown and has to be taken away.

Samir never shows public anger when these relationships end.

He simply moves on to the next one.

But in the privacy of his penthouse, he keeps a laptop that contains something no one else has ever seen.

Folders organized by name and date.

Videos taken from cameras no one knew were there.

Hours of footage of these women in their most private moments, crying in bathrooms, talking to themselves, slowly unraveling.

He watches these videos the way some people watch their favorite films with a kind of detached appreciation for something well-made.

He takes notes.

He reviews his own techniques, what worked, what could be refined, how to make the next one better, because that is what they are to him, not relationships, projects.

In March of 2018, something happens that shatters the clean surface of his life.

He wakes up one morning feeling slightly off, feverish, fatigued in a way that sleep does not fix.

He ignores it for 3 days.

When the symptoms persist, he schedules an appointment at a private clinic across the city, far from Royal Emirates, under a name that is not quite his own.

The doctor orders a full panel.

For days later, the call comes.

There are results that need to be discussed in person.

Samir sits in the examination room the next afternoon and listens as the doctor tells him he is HIV positive.

The viral load is measurable but manageable.

With medication, with careful monitoring, it is no longer a death sentence.

It is a chronic condition.

Treatable, livable.

The doctor keeps talking about anti-retrovirals.

About undetectable equals untransmittable.

About disclosure and safe practices.

Samir hears maybe half of it.

The rest is drowned out by something louder in his own head.

Not fear exactly.

Rage.

He has done everything right.

He is brilliant, successful, careful.

He controls every variable in his life.

And somehow, despite all of that, his own body has betrayed him, made him defective.

For 3 days, he does not leave his penthouse.

He calls in sick at the hospital.

He ignores his phone.

He sits in the dark and runs through every sexual encounter he can remember, trying to pinpoint the source.

The not knowing makes it worse that somewhere someone gave this to him without his permission, without him controlling the situation.

It is the first time in his adult life that he has been genuinely powerless.

On the fourth day, something shifts.

The rage crystallizes into something colder, more focused.

If he has been made defective, someone else needs to carry that.

If his body has betrayed him, someone else’s body needs to reflect that betrayal back.

He needs to regain control not by fixing himself, but by breaking someone else in a way that makes him feel whole.

He begins anti-retroviral treatment under the false name.

He orders medications through a pharmacy that does not ask questions.

He keeps his diagnosis completely hidden from the hospital, from the medical board, from everyone.

And he begins to watch the people around him with new eyes.

What he needs is specific.

Someone foreign so they have no local support system.

Someone lower in the hospital hierarchy so they are used to accepting authority without question.

Someone professional enough to trust medical information.

Someone isolated enough to be grateful for attention.

Over the next several months, he moves through his days at Royal Emirates with a different kind of focus.

He notices which nurses work alone, which ones never seem to have visitors, which ones send money home to families they talk about but never see.

In September of 2018, during a complex surgery, he notices nurse Santos for the first time.

Not because she is beautiful, though she is in an understated way.

Not because she is exceptional, though her work is flawless.

He notices her because of the way she moves through the operating room.

quiet, precise, invisible in the way people become when they have learned that being noticed can be dangerous.

After the surgery, he pulls up her file in the hospital system.

Celestina Santos, age 27, Filipino national, hired March 2016.

Contract renewed once, no disciplinary issues.

Emergency contact is a name in Manila.

Perfect.

Over the next month, he creates opportunities to cross paths with her.

He starts scrubbing in for surgeries where she is assigned.

He makes sure to speak to her directly using her name, thanking her for her work.

Small interactions that cost him nothing but register with her.

He can see it in the way she responds.

A slight surprise each time as if she is not used to being acknowledged.

In October, he escalates.

He finds her in the doctor’s lounge one afternoon during a rare moment when she is alone drinking coffee.

He sits down across from her and asks about her family, where she is from, how she likes Dubai.

She answers carefully, politely, the way employees answer when their boss asks personal questions, but he can see her softening slightly.

The conversation lasts maybe 5 minutes.

When he stands to leave, he tells her she should be proud of her work, that she is one of the most competent nurses on the unit.

That night, alone in his penthouse, he opens his laptop and creates a new folder.

He titles it with her name.

Inside he begins compiling information, shift schedules, known associates, patterns of behavior.

He is methodical about it.

He has learned from previous projects that rushing leads to mistakes.

By December, he has moved to the next phase.

He starts appearing where she goes outside of work.

The coffee shop she stops at on her way home.

The mall where she occasionally walks alone on her day off.

He makes sure these encounters look accidental.

A surprised smile, a friendly wave each time he plants a seed that maybe they have more in common than just the hospital.

She does not suspect anything because there is nothing to suspect.

He is a senior surgeon.

She is a staff nurse.

The power differential is so extreme that the idea of him pursuing her romantically is not even on her radar.

She interprets his attention as kindness, professional respect, which is exactly what he wants her to think.

In January of 2019, he begins sending gifts.

Small things at first.

A box of chocolates left at the nurse’s station with a note thanking the team.

A coffee delivered to her during a long shift.

Then larger things.

A designer scarf because he happened to see it and thought of her.

Each gift is delivered with a story that makes it seem spontaneous, thoughtful, never calculated.

Celestina accepts them because refusing would be rude because he is a doctor and she is a nurse and there are rules about hierarchy that she has learned not to challenge because part of her the part that has been lonely for 3 years is genuinely touched that someone has noticed her at all.

By March of 2019, 6 months into this careful construction, he asks her to dinner.

not as a date.

He clarifies just as colleagues, he values her perspective.

She hesitates.

He sees the hesitation and addresses it immediately.

He knows it might seem unusual, but he genuinely respects her opinion.

And besides, would it not be nice to eat somewhere other than the hospital cafeteria for once? She says yes.

The dinner is at a restaurant in the marina, upscale, but not ostentatious.

He asks about her family, her education, her dreams beyond nursing.

He listens to her answers with the kind of focused attention that makes people feel seen.

He shares carefully edited pieces of his own story, the pressure of living up to family expectations, the loneliness of a career that demands everything.

By the end of the meal, Celestina feels something she has not felt since she arrived in Dubai.

That maybe she is not completely alone.

that maybe this person, this successful, brilliant person, sees something in her worth knowing.

Samir drives her home that night and watches her walk into her building.

Then he pulls up the file on his laptop and adds new notes.

Subject responds well to attention and perceived vulnerability.

Isolation makes her an ideal candidate.

Proceed to next phase.

Over the next four months, he systematically dismantles every boundary between them.

more dinners, weekend drives, invitations to events where she meets his colleagues and feels for the first time like she belongs.

He introduces her to people as someone important, someone whose opinion he values.

Her guard drops completely.

How could it not? He is everything she never thought would notice her.

Wealthy but not cruel about it.

Successful but willing to share that success.

For a woman who has spent 3 years invisible, his attention is intoxicating.

In August of 2019, he schedules the mandatory premarriage medical testing.

U Lol requires it.

He suggests they do it at Royal Emirates where he can handle everything personally.

She does not question it.

She trusts him completely by now.

The day the blood is drawn, he stands beside her in the lab holding her hand, making jokes to ease her nerves.

The technician labels the vials.

Everything looks routine.

That night alone in his office after the hospital has emptied, he accesses the system with administrator credentials he is not supposed to have.

He pulls up the pending results.

His are already in.

HIV positive.

Hers are not processed yet, but the preliminary screening is clear.

Negative.

He sits back in his chair and considers his options.

He could tell her the truth, disclose his status, offer treatment, build a life based on honesty.

The thought passes through his mind and disappears as quickly as it came.

Where would be the control in that? He opens the database fields, changes her result from negative to positive, changes his from positive to inconclusive, requires retest, creates a paper trail that shows a lab error on his sample.

Prince falsified reports on official letterhead.

Takes him less than 20 minutes.

The next morning, he calls Celestina into his office.

His face is serious, concerned, perfectly practiced.

He asks her to sit down.

There has been an irregularity with her results.

She listens as he tells her she tested positive for HIV.

Watches her face collapse, watches her try to make sense of something that makes no sense.

He reaches across his desk and takes her hand.

He tells her that sometimes these things happen.

A needle stick injury she might not remember.

A patient whose blood got into a cut.

She is crying now, shaking her head, saying it is impossible.

He lets her cry.

He holds her hand and says nothing for a long time.

Then softly, he tells her they will figure it out together.

2 days later, he schedules his own retest at a different clinic.

The result, of course, comes back negative because he has made sure it will.

He shows her the paperwork, sits beside her on his office couch, and tells her something that will anchor her to him forever.

This changes nothing for me, Celestina.

I love you.

I choose you.

I choose us.

She cries harder.

Tells him he cannot marry her now.

That it is not fair to him.

That she understands if he needs to walk away.

He looks at her with eyes that have practiced this exact expression in the mirror.

Hurt, resolve, love.

I’m not going anywhere, he says.

And in that moment, she becomes his completely.

Not because she loves him, though she believes she does, but because she now believes she is broken and he is the only person in the world willing to love her anyway.

The wedding is scheduled for October.

The trap is set and Celestina Santos has no idea that the man she is about to marry has already killed the person she used to be.

August 15th, 2019, Dubai.

The premarriage medical testing appointment is scheduled for 9 in the morning on a Thursday.

Celestina wakes up 2 hours early, unable to sleep through the last stretch of night.

She lies in her small room in the staff housing and stares at the ceiling, thinking about paperwork and bureaucracy and all the small official steps that turn two people into a legal unit.

The testing is required by UAE law.

Blood work for genetic conditions, infectious diseases, compatibility markers.

It is routine.

Everyone who gets married here goes through it.

Still, there is something about having your blood drawn, about waiting for results that will either clear you or complicate everything that makes her nervous in a way she cannot quite name.

Samir picks her up at 8:30.

He is relaxed, making jokes about how many forms they will have to fill out, how slow the administrative staff always moves.

He holds her hand in the car.

Everything about his manner says, “This is nothing, just a box to check.

” They arrive at Royal Emirates Medical Center.

He leads her through hallways she knows from work but that feel different now.

She is not here as a nurse.

She is here as a patient, as someone whose body is about to be tested and measured and judged fit or unfit for the future she wants.

The phabotamist is someone Celestina recognizes from the lab.

A quiet Filipino woman named Grace, who has worked at the hospital longer than Celestina has.

Grace smiles at her, makes small talk about the wedding, asks when the big day is.

October 12th.

Celestina tells her.

Just two months away, Grace ties the tourniquet around Celestina’s arm, finds the vein, slides the needle in with practice deficiency.

Three vials, one for blood type and genetic screening, one for hepatitis and other bloodborne pathogens, one for HIV.

The vials are labeled with her name, her employee number, the date.

Grace does the same for Samir.

His blood fills three matching vials, labeled and logged.

The samples are sent to the lab.

Processing time is typically 48 to 72 hours.

Samir tells Celestina not to worry.

These tests almost always come back clear.

It is just procedure.

They leave the hospital together.

He drops her off at her apartment and kisses her goodbye.

She spends the rest of the day in a strange liinal space, waiting for results she is certain will be fine, but cannot stop thinking about anyway.

That night, long after the hospital has emptied and the evening shift has settled into its routine, Samir returns.

He parks in the staff lot and uses his key card to enter through a side entrance.

The security guard at the desk nods at him.

Dr.

Hassan working late again.

Nothing unusual about that.

He takes the elevator to the fourth floor where the administrative offices are located.

His own office is here along with the department heads and the medical records system.

He unlocks his door, closes it behind him, and sits down at his computer.

The hospital database is accessible to senior physicians for legitimate reasons.

They need to check patient histories, review lab results, coordinate care across departments.

Samir has access to all of it.

He also has access to areas he is not technically supposed to reach, permissions he obtained months ago through a combination of administrative oversight and deliberate manipulation of IT protocols.

He logs in and navigates to the lab results portal.

The samples from this morning are still processing, but preliminary data is already visible.

He pulls up Celestina’s file first.

Her blood type is O positive.

Her genetic screening shows no red flags.

Her hepatitis panel is negative.

Her HIV test, still pending final confirmation, shows non-reactive.

Negative.

He sits back in his chair and considers this for a moment.

The woman he plans to marry in 2 months is healthy, uninfected, exactly what anyone would hope for in these results.

Then he pulls up his own file.

Blood type AB positive.

Genetic screening clear.

Hepatitis panel negative.

HIV test shows reactive.

Positive.

The viral load is listed in the notes.

He has been managing his status for 18 months now with anti-retrovirals, keeping it suppressed but not eliminated.

For a long time, he simply looks at the two files side by side on his screen.

Hers clean is marked.

The asymmetry bothers him in a way that is not rational, but is deeply felt.

She gets to be whole while he is defective.

She gets to move through the world without this particular weight.

While he has to carry it forever, he opens the database editing interface.

The system is designed to allow corrections for administrative errors, mislabeled samples, data entry mistakes.

In theory, these corrections are supposed to be logged and reviewed.

In practice, for someone with his level of access, the logs can be edited, too.

He changes Celestina’s HIV result from non-reactive to reactive.

Changes the status from negative to positive.

Adds a note about confirmatory testing needed.

Then he changes his own result from reactive to inconclusive.

Adds a note about possible contamination.

Sample requires redraw and retest.

The changes take less than 5 minutes.

He prints new reports on official hospital letterhead.

The falsified documents look identical to legitimate ones.

Same format, same signatures, same routing numbers.

The only difference is the information they contain.

He erases his tracks in the system.

Adjusts the edit logs to show routine data entry.

Nothing suspicious.

Then he locks the files with administrator credentials so that any future attempts to access them will route through him first.

When he leaves the hospital that night, the security guard waves goodbye.

Dr.

Hassan waves back.

Just another late evening at work.

The call comes 2 days later.

Sunday morning, Celestina is at church with a group of other Filipino nurses when her phone vibrates.

She sees Samir’s name on the screen and steps outside into the heat to answer.

His voice is careful measured.

There is something in his tone that makes her stomach drop before he even says the words.

He needs her to come to the hospital.

There is an issue with her test results.

Nothing to panic about, but they need to discuss it in person.

She makes an excuse to the other nurses and takes a taxi to Royal Emirates.

Her mind is racing through possibilities.

What kind of issue? A genetic marker? Something in her blood work? She tries to remember if there is any family history of disease she should have disclosed.

Samir meets her in his office.

The door is closed.

The blinds are drawn.

He gestures for her to sit down in the chair across from his desk.

She sits.

Her hands are shaking slightly.

He places a printed report in front of her.

Points to a line highlighted in yellow.

HIV antibbody test reactive.

Status positive.

For several seconds, she does not process the words.

They are in English printed in clear professional font, but they do not make sense.

She reads the line again, then again, then looks up at Samir.

This can’t be right, she says.

Her voice sounds strange to her own ears, distant.

There’s been a mistake.

He leans forward, elbows on his desk, hands folded.

His expression is sympathetic, pained, like he is delivering news he wishes he did not have to deliver.

I thought the same thing, he says quietly.

I had them run it twice.

The result is consistent.

She shakes her head.

But I’ve never.

There’s no way I could have.

She trails off trying to map the impossible onto her known history.

She has not had a relationship in years.

She has not shared needles.

She follows universal precautions at work obsessively.

Sometimes it happens through occupational exposure.

Samir says a needle stick.

You might not have noticed a splash of patient blood into a mucous membrane.

It only takes one moment of contact.

Celestina tries to think back through 3 years of ICU work.

How many patients has she cared for? How many IVs has she started? How many tubes has she suctioned? How many times has her gloved hand come into contact with blood or fluid that could have carried something invisible into her body? She feels her throat closing.

Her eyes are burning.

This is not real.

This cannot be real.

Samir comes around the desk and kneels beside her chair.

He takes her hands in his “Listen to me,” he says.

“This is manageable.

With treatment, with the right protocols, people live full normal lives.

This doesn’t change anything about who you are.

But it changes everything.

She knows this immediately.

It changes how she will be seen, how she will see herself.

It changes her status from healthy to infected, from clean to contaminated.

It changes the story she has been telling herself about her life.

You can’t marry me now, she whispers.

The tears start falling.

You can’t.

It’s not fair to you.

Stop, he says firmly.

Don’t do that.

Don’t decide what I can or can’t handle.

Samir, you deserve someone who I deserve.

You, he interrupts.

Exactly as you are.

Do you think I care about a test result? Do you think that changes how I feel? She is sobbing now.

ugly and uncontrolled.

He pulls her into his arms and holds her while she cries.

Over her shoulder, his face is calm, satisfied.

This is going exactly as he planned.

The next three days are a blur.

Samir arranges everything.

He schedules her confirmatory testing at a different facility to make sure there is no lab error.

He sits with her while she waits for those results.

When they come back positive again because he has made sure they will, he holds her while she breaks down.

He begins her on anti-retroviral therapy immediately.

Prescribes the medications himself.

Explains the regimen in careful detail.

She has to take them at the same time every day.

She cannot miss doses.

Her viral load will need to be monitored monthly.

The medications make her sick.

Nausea, fatigue, headaches.

He tells her this is normal.

Her body is adjusting.

It will get better.

She forces herself to take them because he says she has to because she trusts that he knows what is necessary.

She tells no one else.

Not her family, not her colleagues, not her friends from church.

Samir advises her that it is better this way.

People will not understand.

They will judge her.

They will treat her differently.

Better to keep it private.

Between them within a week, she has become completely dependent on him.

He is the only person who knows her secret.

the only person who has not turned away.

She feels a gratitude so overwhelming it borders on worship.

On August 20th, 5 days after the initial results, he shows her his own test report.

This comes back negative.

He tells her he was tested at the same time she was just to be thorough.

He shows her the official paperwork with the hospital seal.

She stares at it.

You’re negative, she says.

The relief and the guilt hit her simultaneously.

I’m negative, he confirms, which means this doesn’t have to touch me.

But I’m choosing to let it because I love you.

Because you matter more to me than playing it safe.

The wedding stays scheduled for October 12th.

She tries to call it off multiple times.

Each time he refuses to listen.

He tells her that love is not about perfect circumstances.

It is about choosing someone even when things are hard, especially when things are hard.

His family knows nothing about her diagnosis.

His friends know nothing.

To everyone else, this is a romance between a successful surgeon and a dedicated nurse.

A fairy tale in a city built on fairy tales.

On October 12th, 2019, they marry at the Burjel Arab.

The ceremony costs 2 million durams, 300 guests, a designer gown that costs more than Celestina earned in her first year of nursing.

Live orchestra, imported flowers, a reception that feels more like a coronation than a wedding.

Celestina walks down the aisle in a fog.

She feels like she is watching herself from outside her body.

The guests see a beautiful bride.

What they do not see is a woman who believes she is damaged, being saved by a man who is actually her destroyer.

When Samir says his vows, he looks at her with perfect sincerity.

When she says hers, her voice shakes, not from joy, from the vertigo of standing at the altar, knowing that she is not the person everyone thinks she is.

The reception lasts until midnight.

They smile for photos.

They dance.

They cut a cake that is four tears tall.

Everyone comments on how lucky she is.

How devoted he must be.

How rare it is to find true love in a transient city like this.

That night they go to his penthouse.

Their penthouse now.

He carries her over the threshold.

The marble floors gleam under recessed lighting.

The floor toseeiling windows frame the city like a postcard.

He gives her the first dose of her evening medication in their new bathroom, watches her take the pills, tells her he is proud of her for being strong.

What Celestina does not know, what she will not know for two more weeks, is that hidden in the smoke detectors and air vents and picture frames are cameras, seven of them covering every room.

Samir waits until she falls asleep.

Then he goes to his study, opens his laptop, and begins reviewing the footage from their wedding night.

He creates a new folder on his desktop, labels it Celestina day 1.

The project has officially begun.

October 13th, 2019.

The first morning, Celestina wakes to an alarm she did not set.

It is 6:00.

Samir is already awake, sitting on the edge of the bed, holding two pills and a glass of water.

Morning medication, he says.

His tone is gentle but firm.

Clinical.

She is still half asleep.

She takes the pills from his hand and swallows them with water.

The moment they go down, nausea hits.

It is the same nausea she has felt every morning since starting antiretrovirals.

But today, it feels worse.

Maybe because this is their first morning as husband and wife, and instead of lying together in bed, she is taking medication for a disease she still cannot fully believe she has.

“I’m going to make breakfast,” Samir says.

“You should rest.

” She lies back down.

The room spins slightly.

She closes her eyes and tries to settle her stomach.

From the kitchen, she hears the sound of a coffee maker, the refrigerator opening and closing, the clink of dishes, normal domestic sounds that should feel comforting, but instead feels strange and distant.

When she finally gets up and walks to the kitchen, he has prepared eggs, toast, fruit.

He plates her portion carefully, tells her she needs to eat to manage the medication side effects.

She forces down what she can.

Every bite sits heavy.

You’re not eating much.

He observes.

I’m trying.

She says the nausea is bad today.

That’s normal.

He replies.

Your body is adjusting.

You need to push through it.

There is something in the way he says it that makes her feel like she is failing.

Like her inability to keep food down is a personal weakness rather than a drug side effect.

After breakfast, she starts to unpack the last of her belongings from the boxes brought over from her old apartment.

clothes, books, small momentos from home as she hangs her shirts in the closet next to his expensive suits.

The difference in their lives becomes physically visible.

Her things look cheap, worn, out of place in this pristine space.

Samir appears in the doorway.

You need to resign from the hospital, he says.

Not as a question, as a statement.

She turns.

What? Your immune system is compromised now.

The ICU is full of infections.

It’s not safe for you to keep working there.

His voice is reasonable like he is explaining something obvious, but I’m on medication.

She says my viral load will be suppressed.

I can still work.

Celestina.

He steps into the room.

I’m a doctor.

I know what’s safe and what’s not.

Trust me on this.

I need to work.

She insists.

I need to send money home.

I need I’ll take care of your family.

He interrupts.

I’ll send whatever they need.

You don’t have to worry about that anymore.

Your job now is to focus on your health.

She wants to argue.

She wants to explain that nursing is not just about money.

It is her identity, her purpose, the thing that brought her to this country and gave her value beyond being someone’s wife.

But when she looks at his face, she sees something that makes her stop.

A kind of hardness beneath the concern.

A sense that this is not really a discussion.

Okay, she says quietly.

I’ll think about it.

Don’t think too long, he replies.

I want you to submit your resignation this week.

He leaves the room.

She stands there holding a blouse, staring at the empty doorway, feeling something shift inside her, something small but important.

The first thread pulled.

By the end of the first week, she has resigned.

The hospital accepts with the usual bureaucratic efficiency.

Her badge is deactivated.

Her locker is cleaned out.

Her colleagues wish her well, tell her how lucky she is to be married to Dr.

Hassan.

How nice it must be not to have to work anymore.

She smiles and thanks them and feels like she is disappearing.

At home, the days blend together.

She wakes to the alarm and the pills.

She eats breakfast while Samir reads news on his tablet and talks about his schedule.

She cleans the apartment even though a housekeeper comes twice a week.

She watches television in languages she does not fully understand.

She video calls her family and lies about how happy she is.

The medication makes her constantly tired.

She naps in the afternoon and wakes up disoriented, unsure what time it is or how long she has been asleep.

Her appetite is gone.

Food tastes like cardboard.

She forces herself to eat because Samir monitors her meals and comments when she does not finish.

He is home every evening by 7.

He asks about her day.

She struggles to fill the time with anything worth mentioning.

cleaned, rested, watched TV.

He nods like these are accomplishments, like she is doing exactly what she is supposed to do.

At night, he initiates sex with the same clinical precision he brings to everything else.

She complies because she is his wife and this is expected, but there is something hollow in it.

He is physically present but emotionally absent.

His eyes, when they look at her, seem to be focused on something else, something she cannot see.

After he leaves the bed and goes to his study, she hears the door close, the lock click.

He stays in there for hours sometimes.

She assumes he is working, reviewing cases, answering emails.

She never asks what he is doing because the closed door feels like a clear boundary.

He has his private space and she has learned not to cross into it.

What she does not know is that on the other side of that door, he is watching her.

The laptop screen is divided into seven camera feeds.

bedroom, living room, kitchen, bathroom, guest room, even the small prayer corner where she kneels, sometimes whispering in Tagalog to a god she hopes is still listening.

He watches her sleep, watches her cry in the shower, watches her stare at nothing for long stretches, her face empty of everything.

He takes notes in a document file.

Day three, increased withdrawal.

Day five, appetite declining, compliance high.

Day seven, depression symptoms visible dependency forming.

This is the part he enjoys most.

Not the destruction itself, but the documentation of it.

The careful cataloging of someone’s psychological collapse.

It is clinical, methodical.

He approaches it the way he approaches surgery with precision and detachment and a quiet satisfaction in his own skill.

October 20th, day 8.

Celestina is in the kitchen at 2 in the morning.

She cannot sleep.

The medication and the depression have destroyed her normal rhythms.

She is awake at strange hours, exhausted at others, never quite aligned with the day.

She opens the medicine cabinet above the sink, looks at the rows of pill bottles, antrovirals she takes twice daily, anti-nausea medication that barely works, sleep aids that leave her groggy, all prescribed by Samir.

All necessary, he says, for managing her condition.

She takes out one of the bottles, turns it in her hands.

The label has her name, the dosage, the refill information, standard prescription, except she never filled this herself.

Samir handles everything, picks up her medications, monitors her compliance.

She has never even been to the pharmacy.

For a moment, she considers what it would be like to just stop, to flush all of it, to see what happens when she does not take the pills that make her feel like a ghost in her own body.

But then she thinks about what Samir has told her.

That these medications are keeping her alive.

That without them her viral load will spike.

That she could develop opportunistic infections.

That she is sick.

And this is what managing sickness looks like.

She puts the bottle back, closes the cabinet, looks at herself in the mirror.

Her face is thinner.

Her skin is dull.

Her eyes are hollow.

She barely recognizes the woman looking back at her.

She thinks about the woman she was 8 months ago before Samir, before the diagnosis when she was a nurse who worked hard and sent money home and had a future that felt, if not bright, at least clear.

That woman is gone.

In her place is someone who apologizes for existing, who asks permission to call her mother, who moves through a luxury penthouse like a servant in her own home.

She walks back to the bedroom.

Samir is asleep.

She slides into bed beside him.

careful not to wake him.

Stares at the ceiling.

Wonders how she got here.

Wonders if there is a way back in his study.

The cameras record everything.

The kitchen scene at 2:00 a.

m.

The woman holding pill bottles.

The defeated slump of her shoulders as she returns to bed.

The next morning, Samir reviews the footage.

He flags it, labels it day eight, suicidal ideiation kitchen, adds it to his growing archive.

He is pleased with his progress.

8 days and she is already exactly where he needs her.

Isolated, dependent, broken.

Soon he thinks it will be time to escalate.

October 27th, 2019.

Day 15.

Morning begins the way every morning has begun since the wedding.

The alarm at 6.

Samir already awake, already holding pills and water.

Celestina takes them without speaking.

Swallows, waits for the nausea to hit.

It always does.

Today is different only in small ways that mean nothing yet.

Samir is rushing.

He has an early surgery, a complex valve replacement that will take most of the day.

He moves through the bedroom quickly, checking his watch, muttering about traffic.

Celestina sits on the edge of the bed in her night gown, watching him.

He pulls on his shirt, buttons it wrong, swears under his breath, starts over.

She wants to help but has learned that offering makes him irritable.

He does not like being reminded that he is imperfect, even in small ways.

I need you to pick up my dry cleaning today, he says, checking his reflection in the mirror.

The ticket is on the kitchen counter.

They close at 6.

Okay, she says, and iron the shirts in the closet.

Some of them have creases.

Okay.

He turns to look at her.

Are you all right? You look tired.

She wants to say that she is always tired, that the medication drains her, that the walls of this apartment feel like they are closing in, that she cannot remember the last time she felt like a person instead of a patient.

“I’m fine,” she says.

He crosses to her, kisses the top of her head.

“Good, I’ll be home late.

Don’t wait up.

” Then he is gone.

The door closes, the lock clicks, the apartment settles into silence.

Celestina sits there for a long time, staring at nothing.

Then she forces herself up, takes a shower, gets dressed in clothes that hang looser than they did two weeks ago, goes to the kitchen to choke down breakfast even though food tastes like ash.

The dry cleaning ticket is where he said it would be.

Next to it, she notices his laptop closed but sitting on the counter.

He usually takes it with him to the hospital.

The sight of it forgotten feels strange.

Samir is meticulous.

He does not forget things.

She picks up the ticket and puts it in her pocket.

Looks at the laptop, looks away, goes to the living room and turns on the television.

Some English language news program.

She watches without processing any of it.

An hour passes, maybe two.

Time has become elastic.

She gets up to get water and passes the kitchen counter again.

The laptop is still there, still closed.

She should not touch it.

She knows this.

It is his private device, his work.

She has no reason to open it except curiosity and boredom and the strange nagging feeling that has been growing in her chest for days now.

The feeling that something is wrong in a way she cannot name.

She stands in front of the counter for a full minute, arguing with herself.

Then she opens it.

The screen lights up.

No password protection.

It opens directly to his desktop.

She stares at the background image.

some default photograph of a beach at sunset.

Folders arranged in neat rows, documents, medical files, research papers, everything labeled in his precise handwriting style.

She is about to close it when she sees a folder in the bottom right corner.

The label makes her pause.

Celestina documentation, her name in a folder on his computer.

She clicks it before she can stop herself.

The folder opens.

Inside our video files, hundreds of them, each one labeled with a date and a description.

She scrolls through them, her heart beginning to pound in a way that has nothing to do with medication side effects.

Day one, bedroom 23:47.

Day 2, shower 7:15.

Day 3, kitchen, 1432.

She clicks on a random file.

The video player opens.

The footage shows her in the bathroom three days ago sitting on the floor of the shower with water running over her.

She is crying.

Her shoulders are shaking.

She stayed in there for almost an hour that day until the water ran cold.

The camera angle is perfect.

Clear view of her face.

She had no idea anyone was watching.

She thought she was alone.

She closes that file and opens another.

This one shows her in the bedroom changing clothes.

Then another her in the kitchen at 2 in the morning holding the pill bottle.

The same night she thought about stopping the medication.

Every private moment, every breakdown, every second she thought was hers alone, all of it recorded, all of it cataloged, all of it watched.

Her hands are shaking so badly she can barely control the mouse.

She scrolls deeper into the folder, finds subfolders organized by room, by activity, by emotional state.

One folder is labeled compliance.

Inside are videos of her taking medication, eating meals he prepared, following his instructions.

Another folder is labeled deterioration.

Inside are the crying sessions, the moments of visible depression, the times she stared at nothing for hours.

There is a folder labeled marital activity.

She does not open it.

She cannot.

She already knows what is inside.

At the bottom of the main folder, she finds a document file, subject analysis C.

Santos.

She opens it.

The document is written in clinical language, observations about her behavior, notes about which techniques increase dependency, assessments of her psychological state.

It reads like a research paper, like she is a case study instead of a person.

Subject shows heightened vulnerability to perceived abandonment.

Isolation from support systems has produced expected results.

Medication regimen contributing to physical weakness and cognitive impairment.

Emotional dependency at target levels.

Recommend continuation of current protocols.

She reads the words twice, three times.

They do not change.

Her vision starts to narrow.

The edges of the screen blur.

She forces herself to keep looking, to keep clicking.

Even though every instinct is screaming at her to stop, she finds another folder.

This one is not labeled with her name.

It is labeled original records.

Keep secure.

Inside are medical documents.

Scanned images of lab results.

Official hospital forms.

She opens the first one.

HIV antibbody test.

Santos Celestina M.

Date August 15th, 2019.

Result: non-reactive.

status negative.

She stares at the word negative, her actual result, the real one, before he changed it.

Beneath that document is another is test result, the one he never showed her.

HIV antibbody test Hassan Samir R.

Date March 12th, 2018.

Result: reactive status positive.

The date is 18 months before he proposed to her.

18 months before he started pursuing her.

He knew he has always known.

There are other documents, screenshots of the hospital database showing his edits, digital evidence of exactly how he switched the results, administrative override codes, timestamps, everything documented with the same precision he brings to surgery.

The world stops moving.

Sound drops away.

Celestina sits in the kitchen of a luxury penthouse staring at proof that her entire reality for the past two months has been a constructed lie.

She is not sick.

She has never been sick.

The diagnosis was manufactured.

The medication was unnecessary.

The shame, the isolation, the complete restructuring of her identity around being infected.

All of it built on nothing.

And the man she married, the man she trusted with everything, has been watching her break, has been documenting it, has been enjoying it.

She stands up from the counter.

Her legs are unsteady.

She walks to the bathroom and vomits into the toilet, her body heaving, even though there is almost nothing in her stomach.

When the spasms stop, she sits on the floor with her back against the wall.

For a long time, she does not move, does not think, just breathes.

Then she gets up, walks back to the laptop, keeps looking.

She finds more folders.

Older ones dated 2015, 2016, 2017.

Other names she does not recognize.

Sarah, Amamira, Michelle.

Each folder contains the same structure.

videos, analysis documents, medical records showing the same pattern, falsified results, manufactured illnesses, systematic psychological destruction.

He has done this before multiple times.

She is not his first victim.

She is his most recent project in a series that goes back years.

The women in these older folders eventually disappear from the timeline.

The videos stop.

No final notes about what happened to them.

Just an end date and the folder archived.

Celestina thinks about the women she has never met.

Wonders if they survived.

Wonders if they know the truth or if they still believe the lies he told them.

Wonders if any of them did what she is thinking about doing right now.

She closes all the folders, clears the recent files list, closes the laptop exactly the way it was.

Then she goes to the bathroom and opens the medicine cabinet.

all the medications he has been giving her.

Anti-retrovirals she never needed.

Anti-nausea medication to counteract the side effects of drugs she should not be taking.

Sleep aids to manage the insomnia caused by psychological torture.

She takes every bottle out, lines them up on the counter, reads each label with a nurse’s trained eye.

Then she opens his private cabinet, the one he thinks she does not know about.

Inside are his real medications, the ones prescribed under a false name to hide his actual HIV status from the medical board.

Anti-retrovirals, dosages carefully calculated for his weight and viral load.

She photographs everything with her phone, the bottles, the labels, the prescriptions, evidence she might need later, if later ever comes.

She puts everything back exactly as it was.

closes the cabinets, wipes down the surfaces, removes all traces that she was looking.

Then she goes to the kitchen and makes lunch.

Mechanically, without thinking, cuts vegetables, boils rice.

Her hands move through familiar motions while her mind is somewhere else entirely.

She is thinking about survival, about what happens next, about whether she can continue living in a world where this man exists and has the power to do this again to someone else.

The question is not whether she wants revenge.

The question is whether she can survive without it.

By the time Samir comes home at 9 that night, Celestina has made a decision.

She does not know if it is the right one.

She does not know if it is moral or justifiable or something she will be able to live with afterward.

She only knows it is the only path forward she can see.

He finds her in the kitchen cooking dinner.

He seems pleased.

You’re feeling better.

He observes.

A little, she says.

Her voice is steady, empty.

Good.

I was worried about you.

He kisses her cheek, goes to change out of his work clothes.

She finishes preparing his favorite meal.

Grilled hamar, saffron rice, fattish salad.

She plates it carefully, adds pomegranate juice in a crystal glass.

In the food in the drink, she has added crushed pills from his own cabinet.

triple the normal dose of his antiretroviral medication mixed with the sedatives from her falsified prescription.

A pharmacological combination that will mimic cardiac arrest or stroke.

In a man with his medical history, with his stress levels, with his age, it will look like a tragic but believable sudden death.

She knows exactly what she is doing.

She is a trained ICU nurse.

She has seen this kind of death before.

She knows the timeline, the symptoms, the way the body will shut down.

She serves him dinner, sits across from him at the marble table, watches him eat.

He talks about his surgery, how successful it was, how the patient is recovering ahead of schedule, how proud the family was.

He is in a good mood.

Expansive.

He reaches across the table and takes her hand.

I’m glad you’re adjusting, he says.

I know it’s been hard, but we’re going to be happy.

I promise.

She nods.

Says nothing.

20 minutes after he finishes eating, he complains of dizziness.

30 minutes, his words begin to slur.

40 minutes, he collapses.

She watches from the doorway as he convulses on the marble floor.

His perfect face finally showing something real.

Terror, confusion, the understanding that something has gone catastrophically wrong inside his body.

She does not call for help.

She does not comfort him.

She takes his phone from his pocket, opens the camera, and starts recording.

“You wanted to watch me break,” she says.

Her voice is clinical, detached.

The voice of a nurse documenting a patient’s decline.

“You wanted to document my destruction.

Now it’s your turn.

” She films everything, the convulsions, the respiratory distress.

The moment his eyes find hers and he understands finally that she knows that she has always been smarter than he gave her credit for.

That he made the fatal mistake of underestimating someone he thought he had completely broken.

When his breathing stops when the convulsions end when the light leaves his eyes, she stops recording.

Deletes the video, wipes the phone, places it back in his pocket.

Then she sits on the sofa and waits exactly 3 minutes.

times it on her watch.

A nurse knows how long it takes for brain death without oxygen.

When the 3 minutes end, she picks up her phone and calls emergency services.

Her voice when she speaks is perfect, cracking in exactly the right places, shaking with exactly the right amount of panic.

My husband collapsed after dinner.

Please help.

I’m a nurse.

I tried CPR, but nothing is working.

Please hurry.

The paramedics arrive within 8 minutes.

Celestina meets them at the door, her face stre with tears, her night gown disheveled from the supposed CPR attempt.

She is the perfect image of a devastated wife.

They rush to Samir’s body on the marble floor, check for pulse, check for breathing, begin their own resuscitation efforts, even though anyone with medical training can see it is too late.

She stands back and watches them work, answers their questions with a shaking voice.

How long has he been down? What was he doing before he collapsed? Has he complained of chest pain recently? She tells them he has been working too hard, long hours at the hospital.

Stress from multiple surgeries.

He mentioned feeling tired today, but she thought it was just exhaustion.

They load him onto a stretcher.

She rides in the ambulance holding his cold hand, crying.

The paramedics try to comfort her, tell her they are doing everything they can.

She nods and continues crying.

at Royal Emirates Medical Center, the same hospital where she used to work, where he falsified her medical records, where he destroyed her life.

They pronounce him dead.

Acute cardiac arrest, likely stress induced, possible undiagnosed coronary condition.

The attending physician, someone who worked with Samir, speaks to her with deep sympathy.

Such a tragedy.

He was so young, so talented.

These things sometimes happen without warning.

Celestina sits in the waiting room in her night gown with an abby borrowed from a nurse.

Her mascara is running.

Her hands are shaking.

A colleague she recognizes from her time working here sits beside her and holds her hand.

He was such a good man, the woman says.

To marry you despite, you know, despite everything.

That’s real love.

Celestina nods, sobs into her hands, says nothing that could be remembered later.

The funeral is held on October 30th.

3 days after his death.

Islamic tradition requires burial quickly.

The ceremony is attended by hundreds Dubai’s medical elite, his family, colleagues, hospital administrators, society figures who knew him from charity events and social gatherings.

Celestina wears black from head to toe.

Accepts condolences with bowed head and appropriate grief.

His mother embraces her, crying, saying that Celestina made Samir’s last month so happy that he spoke of her with such love that she must stay close to the family.

Now his father, the real estate developer whose buildings define parts of the city, shakes her hand and tells her that Samir left her well provided for, that she should not worry about money, that she is family now.

She thanks them, says she cannot think about such things yet, that she just wants to honor his memory.

At no point does she mention the cameras, the falsified records, the other women, the systematic psychological torture.

She buries those truths along with his body.

After the funeral, after the reception, after the last guests leave, she returns to the penthouse alone.

It is the first time she has been here since the night he died.

The marble floors are clean.

Someone from the building staff cleaned up.

There is no evidence that a man collapsed and died here 3 days ago.

She goes directly to his study.

The laptop is where she left it.

She connects an external hard drive and copies everything.

Every folder, every video, every document, all the evidence of what he did to her and to the women before her.

Then she factory resets the laptop.

Destroys the hard drive with a hammer she finds in a utility closet.

Takes the pieces to a dumpster three blocks away and scatters them in different containers.

The external drive with the copies she takes to a storage facility the next day.

Rents a unit under her maiden name.

Locks the drive in a metal box.

She does not know what she will do with this evidence.

She only knows she needs to keep it safe.

December 2019.

2 months after Samir’s death.

Celestina goes to a different hospital for testing.

Not Royal Emirates.

Somewhere across the city where no one knows her.

She requests a full panel.

HIV, hepatitis, everything.

The doctor who reviews her results calls her in for a consultation.

He looks confused.

Your records show you were diagnosed HIV positive in August, he says, looking at the paperwork she brought from Royal Emirates, but your current test shows negative, completely negative.

Not just undetectable, no antibodies at all.

She pretends to be shocked.

How is that possible? Sometimes initial tests can be false positives, he says slowly, especially if there was a lab error or contamination.

It’s rare, but it happens.

So, I never had it according to this test.

No, you’re HIV negative.

Completely healthy.

He pauses.

This is very unusual, but it’s good news.

Remarkable news.

Really? She cries in his office.

Tears of relief that look genuine because part of them is not relief that she is negative.

She knew that already.

Relief that the official record now matches reality.

She never tells him the truth.

Never explains what actually happened.

She simply thanks him and takes her new test results and leaves.

The settlement from Samir’s estate comes through in January 2020.

2 million Dams, about $540,000.

His family insists she take it.

They say he would have wanted her taken care of.

She accepts it, uses part of it to send a large sum home to her family in Manila.

Her mother cries on the phone, thanks God, says this is Celestina’s reward for being such a devoted wife.

Her father says she should be proud that she handled tragedy with grace.

She says nothing to contradict them.

The rest of the money she puts in savings, lives modestly in a smaller apartment.

Does not touch the luxury.

does not want reminders of the penthouse or the marble floors or the man who died there.

In March 2020, she applies to work at a different hospital, not Royal Emirates, somewhere smaller, quieter, where no one knows her story.

She goes back to nursing, back to the ICU, back to the work that gave her identity before everything else.

Her colleagues notice she is different, quieter, more careful.

She does excellent work but keeps to herself.

Does not attend staff gatherings, does not form close friendships.

She is professional, competent, and completely closed off.

One of the senior nurses asks her once if she is okay, if she needs to talk to someone about her loss.

I’m fine, Celestina says.

I just prefer to focus on work.

The nurse does not push.

Everyone grieavves differently.