The elevator doors slide open on the 42nd floor of the Burj Arab, revealing a hallway carpeted in goldthreaded silk.

Chic Herabel Adam stands motionless at the entrance to the presidential suite.

His white wedding kandura now feeling like a costume.

The gold embroidery suddenly garish under the hallways crystal chandeliers.

In his right hand, he grips a manila folder stamped with red letters.

confidential interpol.

In his left, his phone displays 11:47 p.m.

is wedding night, the most important night of his life, now transformed into something unrecognizable.

Behind the suite’s ornate double doors, rose petals form a path to the bedroom.

Champagne sits in a bucket of melting ice.

His bride, Dr.

Dwa Popescu, had excused herself to the bathroom moments before Kareem’s knock shattered everything.

The head of hospital security had apologized profusely, his weathered face tight with urgency.

Shik Herb, I wouldn’t interrupt unless it absolutely couldn’t wait.

Please, 2 minutes now.

Herb stares at the folders contents under the hallway lighting.

Autopsy photographs slide between his trembling fingers.

Bodies with precise surgical incisions.

Victims with hollow expressions frozen in death.

Police reports documenting harvested organs.

black market transactions, 12 confirmed deaths across Singapore from 2017 to 2021.

And in the center of every document, every investigation note, every witness statement, one name appears.

Dr.Diana Padaru, the woman in the surveillance photos has his wife’s face.

What drives a man to marry a monster he mistakes for an angel? What makes a brilliant surgeon trained to save lives, blind to the predator sleeping beside him? This is the story of Shik Herab Aladam, a 41-year-old heir to Dubai’s most prestigious medical dynasty whose fairy tale romance became a nightmare written in other people’s blood.

But to understand what happened in that presidential suite, we need to go back 3 years to where ambition meets deception and love becomes the perfect disguise.

Dubai 1985, the Aladam Medical Center opens its doors in what’s then considered the outskirts of the Emirates.

Shik Muhammad Aladam, Herab’s grandfather, stands before a modest two-story building with his life savings invested in state-of-the-art cardiac equipment.

The family owns nothing else, risks everything on a single belief.

Medicine practiced with excellence and compassion will always find its reward.

By 1995, the center expands to five stories.

By 2005, two additional hospitals open in Abu Dhabi and Sharah.

By 2020, the Alatam Medical Empire is valued at $400 million, employing 2,000 staff, serving 50,000 patients annually.

Harab grows up inside this empire quite literally.

His earliest memories are of evening rounds with his grandfather, watching the old man stop at every bedside regardless of the patients ability to pay.

Medicine, his grandfather would say in Arabic, his hand resting on a construction worker’s shoulder, is the art of seeing the human being, not the bank account.

The patients came from everywhere.

Emirati families who’d known the aladams for generations, European expatriots seeking Western Standard Care, and thousands of South Asian migrant workers who built Dubai’s impossible skyline and lived in labor camps on the city’s edges.

Young Herob notices early that the workers are treated differently, though his grandfather tries to prevent it.

They wait longer.

They receive less attention from junior staff.

They occupy the older wings.

When Herb asks why, his grandfather’s expression darkened.

This is what we fight against, my son.

Every day we fight the human tendency to see some lives as worth more than others.

Promise me you’ll continue this fight.

Herob promises, believing then that the promise will be simple to keep.

His education follows the trajectory expected of an heir to a medical dynasty.

Royal Grammar School in Dubai, where he excels in sciences, rarely socializing but always studying.

Imperial College London for his medical degree, where his research on minimally invasive cardiac procedures earns publication in the Lancet before he’s 25.

John’s Hopkins in Baltimore for his fellowship in cardiotheric surgery where his attending physicians describe him as technically brilliant but emotionally reserved.

He performs his first solo cardiac bypass surgery at 27.

The patient surviving without complications.

The operating room feels like the only place he’s completely certain of his purpose.

By the time Herb returns to Dubai in 2015, age 32, his family’s expectations have crystallized into an unspoken pressure that follows him through hospital corridors.

His two younger brothers have married, produced children, expanded the family tree.

His sister Amamira married at 23 and gave birth to twins by 25.

Their mother, elegant and traditional, begins every family dinner with pointed questions disguised as concern.

Your clinic is thriving, Habibi, but when will you build a family? His father, more direct, reminds him that legacies require heirs.

The hospitals are only half the dynasty.

The family is the other half.

Herb tries.

In 2016, he dates Ila, a marketing executive from a prominent Emirati family.

She’s intelligent, beautiful, shares his cultural background, but she wants a husband who comes home at reasonable hours, who attends charity gallas instead of free clinics in labor camps.

The engagement lasts 4 months before she returns the ring.

You’re married to those hospitals, she tells him without bitterness.

There’s no room for anyone else.

In 2018, he dates Sophia, a French expatriate working in pharmaceuticals.

She understands the medical world, doesn’t complain about cancelled dinners, but after 8 months, she admits the truth over wine in their apartment.

You’re physically here, Herb, but you’re never actually present.

Part of you is always in that operating room.

By 2021, Herb is 38 and has stopped trying.

He tells his mother he’ll marry when he finds someone who understands that his work isn’t separate from his life, but fundamental to who he is.

His father suggests arranged meetings with daughters of medical families.

Herb refuses.

I won’t marry for dynasty politics.

If I marry, it has to mean something.

His grandfather, now 94 and frail, pulls him aside during Eid celebrations.

I waited until I was 41, the old man says, his hand shaking as it grips Herobs.

I thought no woman would understand the calling.

Then I met your grandmother in an operating room.

She was a nurse.

She understood that medicine is service, not profession.

Find someone who understands service and you’ll find your partner.

6 months later, Shik Muhammad Aladam dies in his sleep.

The funeral draws thousands, including patients who traveled from other emirates to pay respects.

Construction workers Herab doesn’t recognize stand in line for hours to offer condolences.

Some crying openly.

Your grandfather treated my father for free.

One tells him, “We had nothing.

He never made us feel worthless.

” At the burial, Harb makes a private vow over the grave.

He’ll continue the mission.

Expand the charitable work.

Make the invisible population visible through dignified care.

This vow, this beautiful intention will become the doorway through which a predator enters his life.

Marina Bay Sands Convention Center, Singapore, March 2022.

3,000 medical professionals from 60 countries converge for the Singapore Medical Innovation Summit.

The conference theme displayed on massive screens.

Ethical healthc care access in developing nations.

Harab attends because the topic aligns with his recent expansion plans.

Aladd hospitals now treat 40% migrant worker patients at reduced rates, a policy his board of directors barely tolerates.

He needs international examples of sustainable models, proof that compassionate medicine can coexist with financial viability.

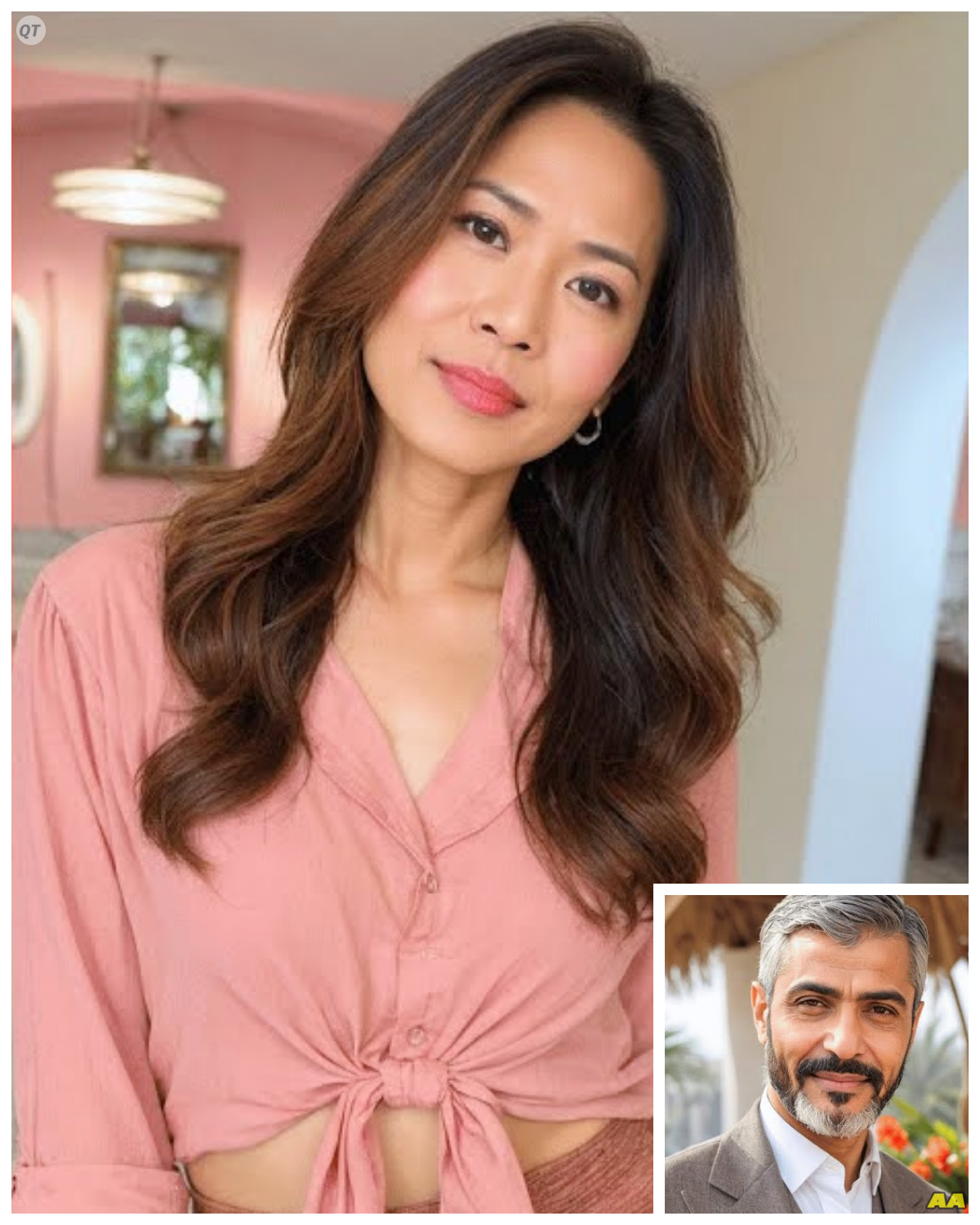

The second day’s keynote panel features five speakers.

Herb sits in row five of the auditorium, his conference program marked with notes, his attention only half engaged until the fourth speaker takes the stage.

Dr.

Diwa Popescu, the name means nothing to him.

The woman it belongs to commands immediate attention.

She’s 5’8, wearing a tailored navy suit that suggests European sophistication without ostentation.

Auburn hair pulled back into a practical bun.

Green eyes that seem to hold genuine warmth even from a distance.

When she speaks, her accent carries traces of Romanian origins softened by years in international environments.

I want to talk about the people we pretend not to see.

She begins, “No preamble, no pleasantries.

The workers who build our hospitals but can’t afford to be patients in them.

The domestic helpers who care for our children but neglect their own health because they can’t take time off.

The invisible population every developed nation relies on but systematically ignores.

For 20 minutes, she presents data from Romanian medical programs serving migrant populations.

Her statistics are precise.

40,000 workers receiving free surgical care annually.

Her methodology is sound.

mobile clinics, culturally sensitive approaches, partnerships with employers.

But what captures Herob’s attention isn’t the data.

It’s her evident passion.

The way her voice breaks slightly when she describes a construction worker who died from a treatable infection because he feared deportation if he sought care.

These people build our cities, she says, her hands gripping the podium.

They construct our towers, clean our streets, staff our restaurants.

We owe them more than reduced rates.

We owe them dignity.

The auditorium erupts in applause.

Herb finds himself standing, clapping longer than necessary, feeling something he hasn’t felt in years.

Recognition.

Someone else understands.

Someone else sees what he sees.

The networking reception occupies the rooftop garden.

Singapore’s skyline glittering against the equatorial night.

Herb navigates through clusters of pharmaceutical representatives and hospital administrators searching.

He finds her by the glass railing, alone, studying the view with an expression he’ll later recognize as calculation, but in this moment interprets as thoughtful solitude.

“Your presentation,” he says, approaching with champagne he doesn’t remember picking up, made me feel less alone in my philosophy.

She turns and her smile transforms her face from merely attractive to genuinely luminous.

“Let me guess,” she says in perfect English, now with barely a trace of accent.

You run a hospital that treats migrant workers.

Your board hates it.

Your family doesn’t understand why you’d risk profitability for people who can’t pay full price.

Herb laughs, startled by her accuracy.

Are you psychic or just experienced? Experienced.

I’ve given that presentation 17 times in 12 countries.

The people who approach me afterward fall into two categories.

Those who want to feel good about themselves without changing anything, and those who actually understand that this isn’t charity.

its basic human decency.

She extends her hand.

Dr.

Diwa Popescu and you are Shik Herabel Adam Dubai.

Something flickers in her eyes too quick to interpret.

Later in prison, he’ll realize it was recognition of opportunity.

In this moment, he mistakes it for connection.

Aladdiac center family.

I’ve read your research on minimally invasive procedures.

Impressive work.

They talk for 2 hours.

The reception ends and they move to the hotel bar.

Conversation flowing with the ease of two people who’ve been waiting to find someone who speaks their language.

She tells him about her background.

Each detail carefully crafted to build trust.

Her father was a factory worker in Romania who died from an untreated respiratory infection when she was 15.

No one cared because he was poor, she says, her eyes distant.

The clinic told him to come back in 3 weeks.

He died in two.

That’s when I decided to become a doctor, to care about the people no one else bothers to see.

Herb shares his grandfather’s death, the promise he made at the grave, his frustration with a medical system that treats health care as commodity rather than right.

She listens with perfect attention, asking insightful questions, nodding at exactly the right moments.

You’re carrying on important work, she tells him.

Too few doctors understand that our expertise is meaningless if we only share it with people who can afford it.

The next three days unfold like a fever dream.

They meet for coffee between conference sessions, both pretending to attend panels while actually sitting in the empty business center talking about everything except medicine.

She’s wellreed quoting Kimu and Roomie with equal facility.

She’s traveled extensively, describing medical work in rural Romania, urban Austria, and recently throughout Southeast Asia as an independent consultant.

I don’t want to be tied to one institution, she explains.

I want to go where the need is greatest.

On the final evening, they walk along Marina Bay, the convention center now behind them, their professional obligations fulfilled.

The topic shifts to the future, to dreams not yet realized.

I want to establish mobile surgical units, she says, her voice carrying genuine sounding enthusiasm.

Equipped operating rooms that can travel to migrant worker populations instead of making them come to us.

Imagine reaching labor camps, construction sites, domestic helper accommodations with actual surgical capacity.

Herob’s mind races with possibilities.

The Aladam hospitals could partner on something like that.

We have the resources, the expertise.

We just need someone with the vision to implement it.

He looks at her backlit by the city’s glow and feels something dangerous.

Hope not just for the work, but for himself.

For the possibility that he’s found someone who won’t make him choose between his calling and companionship.

At Chongi airport the next morning, their goodbye carries the awkwardness of two people trying to appear casual about something that feels significant.

stay in touch? She asks, and he hears the slight vulnerability in her voice that he’ll later understand was completely fabricated.

Absolutely, he says, and means it with an intensity that should have warned him he was already too invested.

What follows is a master class in long-d distanceance manipulation.

For 9 months, they communicate daily through video calls scheduled around time zones.

She’s supposedly in Bucharest, working at hospitals she never names specifically.

contractual confidentiality, she explains when he asks for details.

The institutions I consult with are very protective of their methodologies.

He accepts this because he wants to accept it because questioning feels like suspicion, and suspicion feels like betrayal of the connection he’s certain they share.

Their conversations cover everything.

Challenging medical cases, philosophical questions about suffering and service, poetry they both love, dreams of what they might build together.

She describes helping poor patients in Romanian clinics.

Her voice heavy with exhaustion that sounds authentic.

He shares frustrations with his hospital board who want to reduce migrant worker acceptance rates.

They don’t understand.

He tells her during a call at 2 a.

m.

Dubai time that the mission isn’t separate from the business.

The mission is the business.

You’re rare, she responds, her face pixelated on his laptop screen.

Most doctors lost that idealism by year 2 of medical school.

You’ve kept it for 20 years.

Don’t let them take it from you.

The red flags are there, visible to anyone, not actively ignoring them.

She has no social media presence.

I value privacy in my professional life.

She explains, “Too many patients try to contact doctors outside appropriate channels.

Her video calls always originate from hotels or temporary apartments, never a consistent location.

I travel constantly for consulting work.

I’m rarely in Bucharest for more than a few days.

When he suggests visiting Romania, she deflects smoothly.

My schedule is impossible right now, but I’ll be in Vienna in August for a conference.

Meet me there, he does.

Three days in Vienna feel like falling.

The sensation both exhilarating and terrifying.

She gives him a tour of Vienna General Hospital, speaking knowledgeably about the facilities, mentioning colleagues by name.

What he doesn’t know is she’s memorized staff rosters and is using visitor credentials, playing the role of consultant with practice.

They attend opera at the startup, drink coffee in historic cafes, walk through Shinbrun Palace Gardens.

On the final evening, standing by the Danube as sunset turns the water golden, he proposes without planning to.

I know this is fast, he says, the ring box suddenly in his hand, though he doesn’t remember consciously bringing it.

But I’ve never felt this certain about anything outside an operating room.

You understand me.

You see the world as I do.

Will you marry me? She doesn’t answer immediately.

Later, Hill recognize this pause as her calculating the next move.

In the moment, he interprets it as emotion overwhelming her capacity for words.

When she finally speaks, her voice breaks convincingly.

I never thought I’d find someone who understood me.

Yes, Harab.

Yes, the engagement period should raise more alarms.

When she meets his family in December 2022, his mother embraces her immediately.

Finally, his mother whispers to him in Arabic.

A woman who understands our mission.

His father approves her medical credentials, her apparent dedication to service, her willingness to relocate to Dubai.

Only his sister Amamira seems uncertain, pulling him aside during the family dinner.

She seems rehearsed, Amamira says carefully, like she’s performing the role of perfect daughter-in-law rather than just being herself.

“You’re overthinking,” Herb dismisses, annoyed that his sister can’t simply be happy for him.

“She’s meeting my family for the first time.

Of course, she’s nervous and trying to make a good impression.

The meeting with her family happens via video call.

An elderly woman appears on screen.

Limited English, warm smile, telling stories about Diwa’s childhood that sound authentic because they’re based on the real Diana Padaru’s actual history.

Details Diwa stole along with her identity.

Harab sends monthly financial support to help her mother.

Money that disappears into offshore accounts.

When he suggests visiting Romania, she explains her mother’s health is too fragile for visitors.

She’s embarrassed about our humble home.

Diwa says, “Please don’t push this.

It hurts her dignity.

” So, he doesn’t push.

Love he’s learning sometimes means accepting boundaries even when they feel arbitrary.

The wedding planning escalates beyond anything initially envisioned.

He’d suggested something modest, maybe 200 guests, reflecting their shared values of substance over show.

Diwa insists on Burjel Arab on 900 guests on a $5 million celebration.

This isn’t about us, she explains with perfect logic.

This is about honoring your family’s legacy, showing Dubai society that the Aladam dynasty continues strong.

Your family deserves this pride.

He agrees because her reasoning sounds correct because he mistakes her manipulation for understanding his culture better than he does himself.

The guest list reveals the disparity.

850 from his side, only 50 from hers.

“Most of my family can’t afford to travel,” she explains with apparent sadness.

“But I want you to have everyone who matters to you.

” Her guests, he’ll later learn, are 30 hired actors and 20 actual medical professionals who barely know her, but accepted free trips to Dubai.

3 months before the wedding, Amamira confronts him with evidence from a private investigator.

There are gaps in Diwa’s history, specifically 2017 to 2021.

Years unaccounted for in her official record.

Herb explodes with rare anger.

You investigated my fiance.

This is paranoia, not protection.

You’re jealous that I found happiness.

I’m scared for you, Amamira says, but he’s already leaving the room.

Convinced his sister’s concern stem from something dark in her own character rather than genuine danger.

Two weeks before the wedding, Herb’s medical school friend, Dr.

Chun, mentions casually during the bachelor party.

Singapore had a major organ trafficking scandal in 2021.

Anesthesiologist involved vanished before arrest.

Wild story.

He laughs.

Alcohol making him talkative.

Your Diwa kind of looks like the sketch they circulated.

Actually, weird coincidence.

Herb forces a laugh, but later, alone in his apartment, he stares at Dwa’s photo on his phone.

The thought comes unbidden.

What if? Then he pushes it away violently.

This is pre-wedding anxiety.

Cold feet disguised as suspicion.

He’s 41 years old, trained to analyze evidence, intelligent enough to recognize danger.

If something was wrong, he’d know, wouldn’t he? The answer, as he’ll discover in less than 7 days, is no.

Intelligence provides no immunity against wanting to believe a beautiful lie.

And Da’s lie is very, very beautiful.

May 18th, 2024.

The morning arrives with Dubai’s characteristically aggressive sun.

Temperature already climbing toward 40° C by 9:00 a.

m.

Inside the Aladam family mansion in Emirates Hills, Herb wakes to his phone exploding with messages.

Congratulations from colleagues across three continents.

His mother’s voice echoes through the hallway, coordinating last minute details in rapid Arabic.

His father sits in the breakfast room reading Quran verses.

a family tradition before significant events.

His sister Amamira approaches him on the terrace, her expression conflicted.

It’s not too late, she says quietly, her hand on his arm.

If you have any doubts, any hesitation, we can postpone.

Family will understand.

Herob pulls away gently but firmly.

I have no doubts.

Today, I marry the woman I’ve been waiting my entire life to find.

The certainty in his voice sounds convincing, even to himself.

Amamira nods defeated and walks away.

He doesn’t see her wipe tears that have nothing to do with happiness.

Across the city in a suite at the Burj Arab where Diwa has spent the previous night, a very different preparation unfolds.

She stands before floor toseeiling mirrors.

Her face a mask of concentration as hair stylist and makeup artists work with professional efficiency.

Her laptop sits open on the desk behind her displaying a document labeled integration timeline phase 1.

On the screen, a list of names with accompanying photographs, hospital patients, all migrant workers, all carefully selected over the past 3 months.

She’s memorized every detail, their medical histories, their work schedules, their accommodation addresses, their complete lack of family networks in the UAE.

Her phone buzzes with a message in Romanian from a contact saved only as M.

Buyers confirmed for June deliveries.

Premium pricing secured.

Don’t disappoint.

She types back.

Inventory identified.

Access secured today.

Operations commence within 30 days.

Then she deletes the exchange, closes the laptop, and transforms her expression into one of radiant bridal joy.

The stylists compliment her glow.

You look so happy, one says.

Da’s smile widens.

I’m about to marry into everything I’ve ever wanted, she responds.

And it’s the most honest thing she said in 2 years.

The ceremony begins at 6:30 p.

m.

Scheduled for sunset when the Arabian Gulf transforms into liquid gold and Dubai’s skyline ignites with lights.

The Burj al Arabs terrace has been transformed into something from Arabian Knights mythology, merged with European elegance.

900 chairs upholstered in cream silk with gold accents face and altar constructed from white roses.

50,000 of them imported from Ecuador costing $200,000 alone.

Crystal chandeliers hang from temporary structures, each one weighing 300 lb, their light fractured into rainbows by the descending sun.

The guest composition tells its own story.

In the front rows sit Dubai’s elite government ministers, hospital board members, prominent business families whose connections to the aladam span generations.

Behind them, hospital staff from all three aladam facilities, from senior surgeons to maintenance workers.

Herb had insisted on this.

Everyone who makes our mission possible deserves to witness this.

In the back sections, the 50 guests from Dwa side sit in careful clusters.

Their conversations rehearsed, their backgrounds fabricated.

30 of them paid actors earning a month’s salary for a single evening’s performance.

Herb stands at the altar in traditional Emirati wedding kandura.

White fabric with gold embroidery that took craftsman six weeks to complete.

His brothers flank him as groomsmen, both openly emotional.

His father sits in the front row, hand over his heart, visible pride in his expression.

His mother dabs tears with an embroidered handkerchief.

Only Amira, standing as made of honor in emerald silk, looks troubled, her eyes scanning the crowd as if searching for something she can’t name.

The orchestra begins, a fusion of Arabic and European classical music.

25 musicians playing an arrangement commissioned specifically for this ceremony.

Then Diwa appears at the terrace entrance and 900 people collectively inhale.

The Ellie Saab gown cost $85,000 and looks worth every fills.

Ivory silk flows from a crystal beaded bodice.

The train extending 12 feet behind her, carried by two hired assistants.

Her auburn hair is arranged in intricate braids woven with small diamonds.

Her makeup achieves the impossible, making her look both ethereal and accessible.

A bride from a fairy tale who somehow remains human.

She walks alone down the aisle, no father to give her away, she’d explained.

Her father dead and her mother too frail to travel.

The symbolism isn’t lost on the guests.

A woman who’s built herself from nothing.

Now joining a family dynasty through her own merit.

Herb watches her approach and feels his throat constrict.

She’s the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen.

Not just physically, though she’s objectively stunning in this light, but the totality of what she represents.

Partnership, understanding, shared mission, the end of his isolation.

When she reaches the altar and takes his hands, he whispers in English, “You’re perfect.

” She squeezes his fingers and responds, “We’re perfect together.

” The officient, an Islamic scholar who’s known the Aladam family for 40 years, begins the ceremony.

The vows blend Islamic tradition with personal promises, words carefully crafted over months of planning.

When it’s Herob’s turn, his voice carries across the silent terrace.

I promise to protect you, to honor you, to build with you a life dedicated to service.

I promise to see you always in every moment for exactly who you are.

The irony of these words will haunt him.

He promises to see her for who she is while remaining completely blind to her true nature.

Diwa’s vows are delivered with tears that appear entirely genuine, her voice breaking in exactly the right places.

I promise to be your partner in healing, to use our gifts to help those who suffer most, to never betray your trust.

Her eyes sweep the audience as she speaks.

And later, when investigators review the video footage, they’ll notice her gaze lingering on specific faces.

Hospital administrators, security personnel, board members who control facility access.

She’s not looking at them sentimentally.

She’s cataloging obstacles.

I promise, she continues, her hand tight in Herabs, to honor your family’s legacy and expand it beyond what we can yet imagine.

To see the invisible and serve them with everything we have.

The audience erupts in applause at this, moved by her evident dedication to the Aladam mission.

No one hears the double meaning in her words.

The invisible population she plans to serve will be served on operating tables, their organs harvested for the highest biders.

The first kiss receives cheers and flash photography from a 100 phones.

Herb tastes salt from her tears, from his own tears.

Unsure whose emotion is whose, she leans into him, whispers against his ear.

This is the beginning of everything.

It’s the most truthful statement she’s made all day, though not in the way he interprets it.

The reception transforms the gold ballroom into an Arabian palace from a fever dream.

Ice sculptures of medical symbols, kaducius, DNA helixes, anatomical hearts serve as centerpieces slowly melting throughout the evening.

Champagne towers constructed from crystal glasses cascade with Dom Peragnon.

Fire dancers perform between courses of the five course dinner designed by a Michelin starred chef flown in from Paris specifically for this event.

The famous Lebanese singer hired for $150,000 performs for 40 minutes, her voice soaring over the ballroom as guests dance and celebrate.

The speeches begin at 9:00 p.

m.

Herob’s father approaches the microphone, his formal Arabic translated simultaneously into English through wireless earpieces distributed to non-Arabic speakers.

My son has waited 41 years to find the right partner, he says, his voice thick with emotion.

We worried he would never allow himself the happiness he gives so freely to others.

Tonight, we welcome Dr.

Dwa Popescu into the Aladam family.

You have brought light to our son’s life.

Together, you will expand our medical legacy across the region and serve the populations who need us most.

We trust you with not just our son’s heart, but our family’s future.

The trust phrase will be replayed endlessly during the trial.

Its painful irony dissected by legal analysts and true crime podcasters.

In this moment, it seems merely touching.

A father expressing faith in his new daughter-in-law.

Diwa’s expression during the speech is captured by three different cameras.

Her smile appears warm, grateful, slightly embarrassed by the affusive praise.

But in one photo taken by a guest at an odd angle, her eyes show something else entirely.

satisfaction.

Not the satisfaction of a bride receiving blessing, but of a chess player whose strategy has succeeded perfectly.

Amamira’s made of honor speech comes next, and those who know her well hear the careful word choices, the subtle warnings embedded in conventional sentiment.

Marriage, she says, looking directly at Dwa, is built on honesty, on seeing each other truly without pretense or performance.

May you always choose truth over comfort, transparency over convenience.

May your partnership be founded on who you actually are, not who you pretend to be.

The applause is polite but confused.

The speech feels oddly pointed, lacking the usual warmth.

Herb frowns, making a mental note to ask a later why she couldn’t simply be gracious.

Diwa’s smile never waivers, but her hand on the champagne flute tightens slightly, her knuckles briefly white before she consciously relaxes.

When it’s Diwa’s turn to speak, she takes the microphone with apparent spontaneity, surprising Herab.

This wasn’t planned.

She addresses the crowd in English, her accent lending an exotic quality to her words.

I came from nothing, she begins, her voice carrying across the silent ballroom.

My father was a factory worker who died because the health care system saw him as disposable.

His life was worth less because he was poor.

That injustice shaped my entire career.

When I met Herb, I met someone who understood that every life has equal value.

That our medical expertise is meaningless if we reserve it only for those who can afford it.

She pauses, letting emotion build.

I promise to use every skill I have to serve those your hospitals help.

the workers, the forgotten, the voiceless people who build the city but rarely benefit from its wealth.

Together, Herb and I will ensure that no one is invisible, that every patient receives dignity along with treatment.

This is my vow to you, to this family, and to the legacy I’m honored to join.

The standing ovation lasts 90 seconds.

Guests openly weep.

Hospital staff applaud especially vigorously.

Many of them migrate workers themselves or closely connected to those populations.

Diwa has perfectly articulated the Aladam family mission while simultaneously identifying her hunting ground.

The voiceless people she promises to serve are the same ones she’s already selected for harvesting.

The 23 patients on her laptop, carefully chosen because they’re invisible, now have their invisibility confirmed by a room full of Dubai’s elite, applauding the intention to help them while not actually seeing them as individuals.

The first dance occurs at 1000 p.

m.

to 8,000 years by Christina Perry.

The lyrics about waiting forever for the right person soundtracking Herab and Diwa’s choreographed movements across the floor.

Drone cameras capture aerial footage for the wedding video and social media.

The hashtag #Adam forever trends across UAE Twitter.

Photographs appear on Instagram within minutes, accumulating thousands of likes.

The couple looks perfect together.

his height and her grace, his traditional attire and her contemporary elegance, the symbolism of old money meeting self-made achievement.

During the dance, Herb whispers, “I can’t believe you’re mine.

” Diwa responds, lips close to his ear, “I can’t believe what we’re going to build together.

” The double meaning escapes him entirely.

Meanwhile, outside the ballroom’s golden glow, a different story unfolds.

The hotel staff serving this extravaganza are primarily South Asian and Filipino migrants, servers, kitchen crew, cleaners, the invisible labor force that makes luxury possible.

One server, Akmed Hassan, 34 years old from Bangladesh, balances a tray of champagne flutes as he navigates through the crowd.

He’s been in Dubai for 6 years, sending money home to his wife and three children in Dhaka, living in a labor camp with seven other men in a room designed for two.

Akmed watches the celebration with mixed emotions.

$5 million for a single evening, while his annual salary is $18,000 duroughly $5,000.

The champagne he’s serving costs more per bottle than his monthly rent.

But he doesn’t feel resentment exactly, more a kind of dazed acceptance that this is how the world functions.

Some people have celebrations that cost millions.

Others serve those celebrations and feel grateful for the overtime pay.

What Akmed doesn’t know, cannot possibly know is that he’s already on a list.

Three weeks ago, during his routine medical checkup at Aladam Medical C Center’s free clinic for workers, Dr.

Diwa Popescu accessed his file.

Noted his blood type.

O negative.

Universal donor.

Premium pricing.

Noted his kidney function.

Excellent.

Both organs healthy.

Noted his social situation.

Family in Bangladesh.

No relatives in UAE.

Expired work visa making him deportation vulnerable.

She colorcoded his file green.

Low-risk target.

By Diwa’s calculations, Ahmed’s kidneys are worth $400,000 on the black market.

she’s reestablishing in Dubai.

His life in her assessment is worth whatever brief complications his death might cause before his body is cremated as an unclaimed migrant.

If her plan proceeds as designed, Akmed has approximately 6 weeks to live.

But Akmed serves champagne and watches the beautiful bride dance with her surgeon husband and thinks only about the overtime pay that will let him send an extra 500 durams home this month.

His daughter’s school fees are coming due.

This thought makes him smile as he refills glasses and navigates through Dubai’s elite, completely unaware that the smiling bride has already cataloged his organs and calculated his death.

The evening continues with increasing extravagance.

At 11 p.

m.

, fireworks explode over the Arabian Gulf, spelling out H plus D in gold sparks against the black sky.

The display costs $80,000 and lasts 12 minutes.

Guests film on their phones, posting to social media, marveling at the romance of it all.

By 11:30 p.

m.

, the party is still in full swing, but Herb and Diwa make their choreographed exit.

Tradition dictates the couple shouldn’t stay until the very end.

They’re escorted to a private elevator by the hotel manager himself, accompanied by a security team carrying the gifts they’ll open later.

The presidential suite occupies the 42nd floor, accessible only by private elevator with key card access.

3,000 square ft of luxury.

Master bedroom with king bed dressed in Italian silk.

Bathroom with gold fixtures and a jacuzzi overlooking the gulf.

Living area with panoramic windows.

Private terrace.

Rose petals create a path from the entrance to the bedroom.

Champagne chills in a gold ice bucket.

Chocolate-covered strawberries arranged artfully on crystal plates.

Every surface gleams with the kind of cleanliness that requires a dedicated team.

Herb carries Diwa over the threshold.

Traditional gesture making her laugh.

They toast with champagne, standing at the windows as Dubai glitters 42 stories below.

The city looks like scattered diamonds, beautiful and cold and impersonal.

Tomorrow, Harb says, his arm around her waist.

We start our real life together.

Monday, you officially join the hospital as head of anesthesiology.

Diwa leans into him, her voice warm.

I can’t wait.

I’ve already identified so many ways I can contribute, so many populations we can serve better.

Her laptop sits on the desk behind them.

File open to integration plan 2024, revised.

If Herb looked closer, he’d see patient photographs, detailed medical histories, security schedules for all three Latom facilities, communication logs with black market brokers, revenue projections.

He’d see 23 faces staring out from the screen, 23 people she’s marked for harvest.

But he doesn’t look.

He’s looking at his bride, at her face in profile against the window, at the life he thinks they’re beginning.

I love you, he says, meaning it with an intensity that makes his chest ache.

I love what we’re going to accomplish together, she responds, and he hears this as romantic rather than transactional.

They move toward the bedroom.

The rose petals feel slightly ridiculous under their feet, but also somehow perfect.

The fairy tale gesture matching the evening’s impossible perfection.

Diwa excuses herself to the bathroom, emerges in silk that costs more than Ahmed’s annual salary.

Harb starts to move toward her.

Then his phone vibrates on the nightstand.

He glances at it, preparing to ignore whatever message has arrived, then freezes.

The name on the screen, Kareem Elahir, head of hospital security.

The message emergency.

Sweet 4201 immediately.

Cannot wait until morning.

I’m sorry.

Herob’s first reaction is irritation.

What emergency could possibly justify interrupting his wedding night? But Kareem has worked for the Aladam family for 22 years, served as head of security for 12.

He’s never once contacted Herab outside appropriate hours without genuine cause.

The man’s judgment is impeccable, his discretion absolute.

What’s wrong? Diwa asks, and for just a fraction of a second, so brief, he’ll later question whether he actually saw it.

Her expression shows something other than concern, fear, calculation.

It vanishes before he can process it, replaced by wely worry.

Kareem needs to see me, Harb says, already moving toward the door.

Something at the hospital, I assume.

I’ll be right back.

2 minutes.

He opens the door to find Kareem in the hallway.

The older man’s weathered face tight with obvious discomfort.

In his hands, a manila folder with a red stamp.

Confidential Interpol.

Chic Herab, Kareem says, his voice low and urgent.

I apologize for the timing.

This is unforgivable, but you need to see this immediately before.

He pauses, glances past Harab toward where Dwa stands in the suite.

Before anything else happens tonight, Harb takes the folder, confused.

What is this information about your wife? Her real background.

It arrived from Interpol through our hospital’s legal department an hour ago, flagged as critical urgency.

I’ve spent the last hour verifying its authenticity.

Kareem’s expression is pained.

It’s legitimate.

I’m sorry.

You need to read it now.

The world seems to slow down.

Sounds becoming muffled.

Vision narrowing.

Herb opens the folder under the hallways bright lights.

The first page shows a photo.

It’s Da’s face, but the name underneath reads Dr.

Diana Padaru.

The next page is scroll past in a blur of horror.

Interpol red notice.

organ trafficking, multiple counts of manslaughter, Singapore operations 2017 to 2021, fugitive status, then the autopsy photos, bodies with precise surgical incisions, victims with empty eyes, medical reports detailing harvested organs, police documentation of 12 deaths, 40 survivors permanently disabled.

And in every document, every investigation note, every witness statement, one face appears.

The face of the woman in his bedroom, waiting for him in silk and rose petals.

Harab’s hand starts trembling so violently that pages slip from the folder, scattering across the hallway carpet.

Kareem kneels to gather them, his movements gentle, giving Herab time to process the impossible information.

When he speaks again, his voice carries genuine sorrow.

I’m sorry, Shik Herab.

I should have investigated more thoroughly before the wedding.

This is my failure.

But Herb barely hears him.

His mind is racing through two years of courtship.

Every conversation, every shared dream, every promise, all of it lies, all of it performance.

The woman he married doesn’t exist.

The woman who exists is a monster wearing a perfect mask.

He thinks of his grandfather’s grave, the vow he made to serve the invisible population.

He thinks of the 23 patients she mentioned improving care for and suddenly understands with crystallin horror that improving care meant something entirely different to her than to him.

He thinks of Akmed serving champagne downstairs, of the thousands of migrant workers who trust Aladam Hospitals because of his family’s reputation for dignity and compassion.

She was going to use that trust to hunt them.

She was going to turn his family’s legacy into an abattoire.

She was going to make him complicit in mass murder.

The folder contains one final document, a Dubai police intelligence report compiled in the last 3 hours based on Diwa’s laptop activity traced through the hotel’s Wi-Fi.

A list of 23 names with photographs, hospital patients, all migrant workers, all selected over the past three months, all marked with color codes, green, yellow, red, indicating harvesting priority.

Harab recognizes some of the faces from his rounds.

He’s treated these people, shaken their hands, promised them care, and his wife, his wife, has marked them for death.

Something fundamental breaks inside him in that hallway surrounded by scattered pages and rose petal perfumed air.

Not just his heart, but his understanding of reality, his faith in his own judgment, his belief that love and service can coexist with safety and trust.

If he could be this wrong about the person he married, what else has he been wrong about? If a monster can wear such a perfect mask, how does anyone ever know who they’re truly looking at? What do I do? he asks Kareem, his voice barely audible.

The older man’s expression is impossibly sad.

You call the police.

You have her arrested.

You enol the marriage.

You protect the patients on this list and honor the memory of her victims.

He pauses.

There is no other option.

She Herob, I’m sorry, but standing there in his wedding kandura with autopsy photos at his feet and his bride waiting in the bedroom, Harb thinks there’s always another option.

It’s just a question of whether you’re capable of taking it.

He picks up the folder with steady hands, squares his shoulders, and walks back into the suite where his wedding night is about to become something unrecognizable.

Behind him, Kareem remains in the hallway, uncertain whether to follow or give privacy to whatever horror is about to unfold.

He chooses privacy and will regret this decision for the rest of his life.

Herb enters the presidential suite and closes the door with deliberate quietness.

The soft click of the latch somehow louder than any slam could be.

Diwa sits at the vanity removing her wedding jewelry.

Her movements graceful and unhurried.

She sees his reflection in the mirror and immediately her body language shifts.

Shoulders tensing, hands pausing mid-motion, eyes sharpening with alertness.

She doesn’t ask what’s wrong.

She already knows something has changed.

Can sense it in the air between them like animals sense approaching storms.

Kareem brought me something interesting,” Herb says, his voice surprisingly steady.

He walks to the bed and drops the manila folder onto the silk sheets.

The heavy thud of paper on fabric somehow obscene.

Autopsy photos scatter across the space where they were supposed to consummate their marriage.

Death imagery among rose petals, creating a tableau of symbolism so perfect it seems staged.

Diwa turns from the vanity, studies the scattered documents, and her face does something extraordinary.

The mask doesn’t crack slowly.

It doesn’t slip in stages.

It simply vanishes in an instant, replaced by something cold and calculating and utterly devoid of the warmth he’s seen for 2 years.

The transformation is so complete, it’s like watching one person replaced by another.

A magic trick where the assistant disappears and someone entirely different emerges from the box.

So, she says, her voice different now.

Flatter, harder, stripped of its careful warmth.

Interpol finally caught up.

I wondered how long that would take.

The casual admission hits harder than denial would have.

Part of Harab still hoped for innocent explanation.

Mistaken identity, elaborate coincidence.

Her immediate confirmation of guilt destroys that last desperate fantasy.

“Tell me it’s not real,” he says, hating the pleading tone in his voice.

Tell me this is a mistake.

Someone with your face.

Wrong identification.

It’s real.

She stands and walks to the bed, picks up one of the autopsy photos.

A man in his 30s, chest opened, organs removed with surgical precision.

She studies it clinically without emotion.

Rajeskumar, construction worker from Tamil Nadu, 31 years old.

He had cerosis from years of chemical exposure at building sites.

He was dying anyway, maybe 2 years left.

I removed both his kidneys because his liver was too compromised for harvest.

He died of sepsis 72 hours after the procedure.

She recites these facts like reading from a medical chart.

No more emotion than if discussing weather patterns.

Herb feels his stomach contract.

Nausea rising.

You talk about him like he was inventory.

He was inventory.

Diwa sets down the photo.

Picks up another.

Maria Adlawan, domestic helper from the Philippines.

34 years old, supporting three children back home.

She had excellent renal function.

I took both kidneys during what she thought was an apppendecttomy.

She died on the table from hemorrhage.

That was unfortunate.

I lost the organs when she died.

Unfortunate, Harb repeats, the word tasting like poison.

You killed a mother of three, and your concern is the lost organs.

Diwa’s expression shows genuine confusion at his horror, as if he’s being unreasonably emotional.

The children still had no mother, whether she died in three years from untreated diabetes or on my table.

At least her death served a purpose.

Her kidneys would have saved two lives, wealthy patients who contribute to society.

Instead, she died for nothing.

That’s the unfortunate part.

The logic is sociopathic, but internally consistent, and that somehow makes it more horrifying.

Herob sinks onto the bed, his legs suddenly unreliable.

“Who are you?” “Because the woman I married wouldn’t, couldn’t.

The woman you married doesn’t exist,” Diwa interrupts.

She moves to the desk, opens her laptop with casual confidence.

No longer concerned with hiding anything.

Dr.

Diwa Popescu is a character I created, based partially on a real person who conveniently died in 2019, making her credentials available for purchase.

I’ve been playing that role for 3 years.

Before that, I was Diana Padaru.

Before that, other names.

The core person underneath all those identities.

She’s always been exactly what you see now.

She turns the laptop screen toward him, showing the file labeled integration plan 2024, revised.

23 faces stare out from meticulously organized profiles.

Each entry includes photograph, medical history, kidney function scores, family status, security risk assessment.

Color-coded tags, eight green, 11 yellow for red.

At the bottom, financial projections.

Estimated annual revenue $6.

2 million USD.

Operational costs $400,000.

Net profit $5.

8 million.

Proposed split 50/50ths.

Split.

Herb’s voice cracks.

You thought I would? You actually believed I’d participate in this.

Diwa’s expression shows surprise at his shock.

Why wouldn’t you? You’re a surgeon.

You understand organ supply and demand.

There are 10,000 people waiting for kidneys in the Middle East right now.

Legal channels can’t meet that demand.

I provide a service that the market desperately needs by murdering people, by harvesting from donors who are dying.

Anyway, her tone suggests she’s explaining something obvious to a slow student.

Look at the files, Harb.

Really, look.

Every green tagged patient has life expectancy under 5 years.

Construction workers with chemical damage, domestic helpers with untreated chronic conditions, laborers with occupational injuries that will kill them eventually.

I’m not targeting healthy young people with decades ahead of them.

I’m selecting those already on trajectories toward early death.

She clicks through the profiles.

Her commentary clinical and efficient.

Akmed Hassan, 34, the server from tonight.

Stage two kidney disease from workplace chemical exposure.

Undiagnosed until I reviewed his blood work.

Maybe 7 years left if he gets treatment he can’t afford.

His kidneys are still functional now.

Worth 200,000 each.

In 7 years, they’ll be worthless.

His death is inevitable.

I just accelerate the timeline and give it economic value.

He has a wife, children.

Herob’s voice sounds distant to his own ears, like he’s hearing himself from underwater, who will suffer regardless of when he dies.

Diwa’s tone carries no malice, just matterof fact assessment.

If anything, earlier death means less prolonged suffering for him, and the money from his organ sales, if properly directed, could provide for his family better than his construction wages ever will.

I’m actually doing them a favor.

The rationalization is so grotesque.

so perfectly constructed that Herob can’t immediately formulate response.

She’s taken the invisible population he wanted to serve and turned them into livestock.

Their poverty and vulnerability transformed from injustice to opportunity.

And she’s done it using the exact medical infrastructure he built to help them.

The Aladam hospitals, he says slowly, understanding crystallizing.

You targeted me for access obviously.

She closes the laptop, sits on the bed facing him with unsettling casualness.

I researched extensively before Singapore.

Needed a medical institution with three key characteristics.

High migrant patient volume, reduced security scrutiny for charitable cases, and a reputation that would deflect suspicion.

Your hospitals checked every box.

Plus, you personally were perfect, single, lonely, desperate for someone who understood your mission.

Easy to approach, easy to convince, easy to manipulate.

Each word lands like a physical blow.

Our entire relationship was calculated.

Every conversation, every shared dream, every moment of apparent connection, all designed to build your trust and secure my access.

She pauses, considering though I will say you made it easier than expected.

You wanted so badly to believe someone understood you that you ignored every warning sign.

Your sister tried to tell you that Chun friend mentioned the Singapore case.

Your security chief had suspicions, but you dismissed them all because you were so grateful someone finally saw you.

Her smile is almost pitying.

Lonely people are the easiest targets.

Herb thinks of Amamira’s warnings, the private investigators findings he rejected, Dr.

Chen’s drunken observation about the organ trafficking sketch.

Every red flag he’d explained away.

Every suspicion he’d reframed as paranoia or jealousy.

She’s right.

He’d been so desperate for connection that he’d collaborated in his own deception.

The wedding, he says, the full horror dawning.

$5 million.

My family welcomed you.

900 people celebrated.

An excellent investment.

Diwa’s business-like tone makes it worse.

5 million to establish complete trust, gain legal access through marriage, and position myself as head of anesthesiology with database access and surgical authority.

Conservative projection suggests 20 organs harvested per year at average $200,000 each.

That’s 4 million annually.

I recoup the wedding cost in 18 months and net $35 million over a decade.

From a pure ROI perspective, marrying you was brilliant strategy.

She stands, walks to the window, studies the Dubai skyline with proprietorial satisfaction.

Your hospitals are perfect for this, Herab.

Three facilities, thousands of migrant patients, minimal family networks to complicate disappearances.

I’ve already modified consent forms to allow additional procedures as medically necessary.

I’ve identified storage facilities for immediate posth harvest preservation.

I’ve established contracts with buyers across Asia, primarily Chinese and Malaysian elite, willing to pay premium prices for well-maintained organs from relatively young donors.

You’ve been planning this for months.

The timeline makes him dizzy.

While we planned the wedding, while you met my family, while you while I performed the role of loving fiance.

Yes, it’s called multitasking.

She turns from the window, her green eyes cold in the sweets soft lighting.

The first harvesting was scheduled for 3 weeks from now.

Akmed Hassan color-coded green low risk simple procedure disguised as exploratory surgery for his chronic abdominal pain.

Remove both kidneys, repair the incisions, put him in recovery with strong painkillers.

He’d die from complications within 72 hours.

We document it as unexpected surgical outcome.

Cremate the body before anyone could request detailed autopsy.

The buyers are already secured 200,000 per kidney for 100,000 total.

That would have been our first return on investment.

She still uses that word, still believes on some level that he’ll participate once he understands the economics.

Herb stares at this woman he thought he knew and sees a complete stranger.

Someone whose moral framework is so alien it might as well be extraterrestrial.

You really think I would have helped you murder patients in my own hospitals? Eventually? Yes.

She sits beside him on the bed, close enough that he can smell her perfume, the same scent that’s comforted him for two years now, making him nauseous.

Not immediately.

I was going to conduct the first few operations independently, present them as unfortunate complications, let you see how easily it could be done, then gradually bring you into awareness, show you the revenue, demonstrate that these people are dying anyway.

I estimated 6 months before you’d actively participate.

Maybe a year before you’d acknowledge it openly.

But you would have come around.

People always do when enough money is involved.

No.

The word comes out fierce, almost violent.

I would never.

You already do.

Her interruption is sharp.

Cutting.

That’s what you don’t want to admit.

You profit from their labor while paying substandard wages.

You provide reduced rate care, but still charge enough to maintain profit margins.

You’ve built a reputation on helping the poor while living in a mansion in Emirates Hills and driving a car worth more than they’ll earn in their lifetimes.

The only difference between us is I’m honest about the extraction.

You pretend yours is charity.

The accusation hits something true and Herob feels his certainty waiver.

He does profit from migrant labor.

His hospitals do charge reduced rates that are still unaffordable for many workers.

He has built a comfortable life on the backs of people whose suffering he claims to alleviate.

The distance between his position and Diwa’s is wider than hers obviously, but is it as absolute as he wants to believe? That’s different, he says, but his voice lacks conviction.

Medical care costs money.

Hospitals require staff, equipment, facilities, and organ harvesting requires surgical skill, storage facilities, distribution networks.

Her smile is sharp.

We’re both extracting value from vulnerable populations.

Herb, I just extract literal organs while you extract economic ones.

You judge me, but we’re operating on the same spectrum.

You’re just uncomfortable acknowledging it.

No, he stands abruptly, needing physical distance from her and the poisonous logic she’s spreading.

No, there’s a fundamental difference between imperfect charity and serial murder.

You’re trying to blur boundaries that are actually very clear.

Am I? She remains seated, relaxed, confident.

Look at the profiles again.

Akmed Hassan, seven years left, dying in a labor camp, sending money home that barely feeds his children.

If I harvest his kidneys and put $200,000 in a trust for his family, haven’t I actually improved the net outcome of his life? He dies either way.

This way, his death has meaning.

His family gains financial security.

Two wealthy patients receive life-saving organs.

Everyone wins except Akmed who was going to lose anyway.

He doesn’t get to choose.

Herob’s voice rises.

You’re deciding for him that his life is worth less than the lives of people who can afford black market organs.

You’re playing God with the most vulnerable.

We all play God.

Dwa stands now, her posture aggressive.

Every time you decide which patient gets the available surgery slot, you’re choosing who lives and who waits.

Every time your hospital allocates resources to profitable departments over charitable ones, you’re deciding whose suffering matters.

Every time you go home to your mansion instead of working another shift, you’re choosing your comfort over someone else’s life.

The only difference is I acknowledge the calculations you pretend don’t exist.

They’re shouting now.

Two medical professionals in wedding attire arguing philosophy over scattered autopsy photos.

The absurdity of the scene somehow matching its horror.

Outside the windows, Dubai glitters in unconscious beauty.

The city built by the same migrant workers they’re debating the value of.

If you really believed I’d participate, Harb says, forcing his voice lower.

Why did you make yourself into a bomb? You told me yourself.

Expose you and I destroy my family’s reputation, my hospitals, everything.

You set up a hostage situation.

Insurance? She shrugs.

In case you took longer than expected to come around, the threat of mutual destruction keeps you from calling the police while we work through your moral hesitation.

Eventually, you’d realize that protecting your family’s legacy requires protecting me, which means allowing the operations to continue.

Interdependence creates alignment.

Except it doesn’t.

Herb picks up his phone from the nightstand because you’re wrong about me.

You researched my hospitals, my reputation, my vulnerabilities, but you didn’t understand the one thing that actually matters.

I meant every word I’ve ever said about serving these populations.

They’re not theoretical to me.

They’re not economic units.

They’re human beings who deserve dignity and protection.

For the first time, Dwa’s confidence falters slightly.

You’re going to call the police? Destroy yourself to stop me if that’s what it takes.

She moves fast, crossing the room to grab his wrist.

Her grip surprisingly strong.

Think about what you’re doing.

Your father’s heart condition.

This stress could kill him.

Your mother, your sister, the hospital staff, thousands of people depend on the aladam reputation.

You call the police.

It all ends.

The hospitals close.

Your family becomes synonymous with scandal.

And for what? To stop something that’s already happening across the world.

I’m not unique Herab.

If not me, someone else will fill this market need.

But it won’t be in my hospitals using my name, destroying my family’s actual legacy.

He pulls his wrist free.

You’re right that I profited from extraction.

You’re right that I’ve participated in systems that devalue migrant lives, but there’s a line between imperfect charity and deliberate murder, and I won’t cross it.

I can’t.

Can’t.

Her expression hardens.

Or won’t.

Because here’s what you’re not considering.

I have recordings, conversations where you discussed flexible ethics for migrant care, comments about resource allocation that sound very different out of context.

I’ve documented every moment of our relationship.

You think you can have me arrested without becoming complicit.

I’ll testify that you knew everything, that you approved the plan, that you married me specifically to provide cover for operations you’ve been contemplating for years.

No one would believe that.

Dubai police investigating the pristine al-AM family.

They’ll believe whatever narrative fits the evidence I provide.

I’ve been building that evidence for 2 years.

She pulls her own phone from the vanity, opens a recording app showing dozens of files.

Every call, every conversation, every moment you complained about hospital economics or difficult patients edited correctly, you sound like a man planning exactly what I’m accused of.

Herb stares at the phone, understanding the trap’s full scope.

She hasn’t just made herself a bomb, she’s made him the detonator.

Expose her and the explosion takes him to protect himself and he enables future murders.

The choice she’s offering isn’t between good and evil, but between two different forms of destruction.

There’s always a third option, he says quietly, his surgical mind beginning to work through a different kind of problem.

Diwa’s eyes narrow.

What option? Instead of answering, Herob walks to the suite’s medical emergency kit mounted on the wall near the bathroom.

Every presidential suite in Burjal Arab contains one standard safety protocol for guests who might need immediate medical intervention.

He opens the case, examining contents with professional efficiency, scalpels, sutures for equipment, emergency medications, including he notes with grim satisfaction, veuronium bromide, 10 mg pre-measured vial.

the same paralytic agent she used on her victims.

What are you doing? Diwa’s voice carries uncertainty now.

The first genuine fear he’s heard from her tonight.

Herb doesn’t answer immediately.

He’s thinking about Akmed Hassan serving champagne downstairs.

About the 23 faces on her laptop marked for harvest.

About the 12 dead in Singapore whose families never got justice.

He’s thinking about his grandfather’s grave and the promise he made to protect the vulnerable.

He’s thinking about Diwa’s recordings, her threats, the hostage situation she’s created that prevents traditional justice.

And he’s thinking about something else, something darker that he barely recognizes in himself.

Rage.

Pure incandescent fury at being used, at having his love weaponized, at watching his life’s work perverted into hunting ground for a predator.

The anger is so intense it feels physical, like electricity through his nervous system, like fire in his chest.

You know what the truly horrifying thing is? He says, still facing the medical kit.

Part of me understands your logic.

The migrants, the workers, they are invisible.

I do profit from systems that exploit them.

The distance between us is smaller than I want to admit.

He turns the vial of veuronium broomemide in his hand.

And that’s exactly why you can’t be allowed to live.

The presidential suite exists in suspended time.

Dubai skyline glittering through floor to-seeiling windows while inside everything has stopped.

Herb holds the vial of vecuronium bromide with steady surgeon’s hands.

The clear liquid catching soft light betraying nothing of its lethal purpose.

Diwa steps backward, her expression shifting through visible calculations.

Fight, flight, or negotiate.

Her brain processing options with clinical efficiency.

Herob, she says, her voice modulating into warmth, attempting resurrection of the bride persona.

You’re not thinking clearly.

Put that down.

We can work through this.

Work through this.

He moves toward the desk, unwrapping a syringe with hands, operating independently of conscious thought.

20 years of training.

Guide his movements.

Attach needle.

Draw medication.

Check for air bubbles.

You want to negotiate after telling me you plan to murder patients in my hospitals? I want you to consider consequences before making irreversible choices.

She’s backing toward the door now, maintaining distance.

You’re angry, betrayed, but this isn’t you.

You’re a healer.

You don’t have violence in you.

The syringe fills with 10 milligs of death.

Herb studies it with professional detachment procedural habits too ingrained to abandon.

You’re right that I’ve spent 20 years saving lives, but you’ve spent years taking them using the same skills, the same training.

The only difference between healing and killing is intention.

He crosses the room faster than she anticipates.

Surgical precision translating to physical efficiency.

Diwa reaches for the door handle, but he’s already there gripping her wrist.

He finds the vein in her anticubital fossa where veins run close to surface.

The needle slides in with practiced ease.

His thumb depresses the plunger.

3 seconds.

No.

The word cuts off as Veironium begins its work, blocking neurotransmission at the neuromuscular junction.

Within 15 seconds, voluntary muscle control fails.

Within 30 seconds, complete paralysis.

Diwa’s eyes widen in understanding and terror.

Her mouth opening to scream but producing no sound.

Her legs buckle and Herob catches her, lowering her to the floor with the same careful attention he’d use positioning a patient on an operating table.

She lies supine on rose petal scattered carpet, body completely immobilized except involuntary functions, heartbeat, pupil dilation, tear production.

Her eyes track his movement with desperate intensity, fully conscious, fully aware, experiencing exactly what she inflicted on 12 victims in Singapore.

The paralysis extends to her diaphragm within 45 seconds.

She can no longer breathe independently.

Herob kneels beside her, his face hovering above hers.

Rajeskumar felt this, he says, voice clinically calm.

When you told him he needed a routine procedure and he trusted you because you were a doctor, he felt the paralysis setting in.

Felt his lungs stop working.

Maria Adlawan felt this.

the mother of three who died on your table while you harvested her organs.

Diwa’s tears leak from the corners of her eyes, tracking down her temples.

Her pupils are fully dilated.

The body’s panic response unable to manifest any other way.

He stands, walks to the bed, retrieves one of the decorative pillows, cream silk with H and D embroidered in gold thread.

The monogram that was supposed to represent their unified future now becomes instrument of death.

Returning to her paralyzed form, he kneels again, positioning the pillow above her face.

Her eyes track the pillow’s movement with desperate focus of prey watching predators approach.

I wanted to call the police, Harb says, his voice cracking.

I wanted justice through proper channels.

But you made yourself into a bomb that would destroy everything.

You threatened my family, my hospitals, the patients who depend on us.

He places the pillow over her face, not pressing yet, just positioning.

So, I’m doing what you taught me to do.

I’m making a calculation.

Your death saves 23 people you’ve marked for harvesting.

His hands press down steady and firm.

The pillow compresses against her face, blocking air her paralyzed diaphragm was struggling to move.

Her body cannot thrash.

Her limbs cannot fight.

The veuronium has made her a prisoner in her own flesh.

Conscious but helpless.

exactly as she designed for her victims.

Time becomes elastic.

Medical training provides clinical awareness of the process.

Oxygen deprivation begins immediately.

The brain can survive 4 to 6 minutes without oxygen before irreversible damage.

Death from complete deprivation takes 6 to 8 minutes.

He knows this academically has studied it in textbooks treated patients who suffered hippoxic events.

But knowing clinically is different from causing deliberately.

Minute one.

Her body attempts to breathe.

Autonomic system triggering reflexive gasps.

Her paralyzed muscles cannot execute.

Small blood vessels in her eyes begin to burst.

Patiki.

Tiny hemorrhages indicating asphyxiation.

Minute two.

Her pulse accelerates.

The heart pumping frantically, trying to circulate oxygen that isn’t there.

Her skin begins changing color.

Healthy tone fading toward gray.

Minute three.

The eyes lose some of their desperate focus.

Cognitive function declining as the brain starves.

Consciousness beginning final retreat.

Harab continues pressure with unwavering steadiness.

His surgeon’s hands trained to maintain exact force without fatigue.

But his face tells different story.

Tears flowing freely, jaw clenched so tightly his teeth ache.

Sounds emerging from his throat that are neither words nor sobs, but something more primitive.

Minute four.

Her pulse weakens perceptibly.

The heart struggling, running out of oxygen for its own tissue.

Her eyes still open, but pupils dilated further.

Brain’s desperate search for sensory input.

Minute five.

Subtle relaxation in her body.

The bladder releasing.

Autonomic control failing.

The smell of urine mixes with rose petals and expensive perfume.

Alactory evidence of the body’s final surrender.

Minute six.

Pulse nearly imperceptible.

Her eyes fixed in position, no longer tracking movement.

Petikquiki eyes spread across her scara.

Her skin progressed past gray toward faint blue cyanosis visible mark of oxygen deprivation.

Minute seven.

No pulse he can detect.

Her eyes remain open but completely still, fixed in midilation.

Expression neither peaceful nor agonized but simply absent.

What made Diwa Popescu has departed, leaving only cooling tissue? Minute 8.

Herob maintains pressure 30 seconds past last detectable pulse.

Medical training demanding thoroughess even in murder.

When he removes the pillow, her face shows unmistakable evidence of asphyxiation.

Petiki eye extending beyond eyes to facial skin.

Blue gray palar fixed pupils.

Slight foam at lips from lungs.

Final attempts at gas exchange.

He sits back on his heels, pillow still in hands, staring at what he’s done.

The woman who was his bride 2 hours ago is now a corpse on the presidential suite floor surrounded by rose petals that now seem like funeral decorations.

Her face is frozen in an expression that will haunt him forever.

Not quite fear, not quite accusation, but something encompassing both.

Herb’s first instinct is to check for pulse, attempt resuscitation.

20 years of medical training overriding deliberate killing.

His fingers move to her corateed artery before conscious thought stops them.

She’s dead.

He killed her.

Resuscitation would only restore the monster.

His second instinct is pure overwhelming horror at himself.

He looks at his hands.

The same hands that have repaired hearts, saved hundreds of lives, held patients hands while delivering news.

These hands just killed someone with premeditation and full awareness.

He is now what he claimed to be different from someone who uses medical knowledge to kill.

The third instinct is practical procedural.

He has perhaps 30 minutes before hotel staff might notice something wrong.

He works with robotic efficiency.

Conscious mind dissociating from actions his body performs.

First he removes syringe and vial.

The vial goes in bathroom trash.

A mistake he doesn’t catch now.

Judgment compromised by shock.

The syringe he breaks down.

wrapping needle in toilet paper, disposing of pieces separately.

Next, he repositions Diwa’s body, drags her to location beside the bed where someone might plausibly collapse from sudden cardiac event, arranges limbs naturally, removes urine stained night gown, replaces it with clean pajamas from luggage, bags, soiled garment.

The clinical detachment required feels like watching someone else manipulate a corpse.

He changes his own clothes.

Wedding kandura replaced with casual attire.

Places pillow back on bed.

Checks room for evidence.

Eyes scanning with systematic attention he’d use reviewing an operating room before surgery.

Only then does full magnitude crash over him.

He sinks onto the bed beside where his dead wife lies.

Hands shaking now that they’re no longer occupied.

He’s killed someone.

He’s a murderer.

Regardless of her crimes, regardless of justifications, regardless of the 23 potential victims he saved, he has deliberately ended a human life.

The clock shows 12:11 a.

m.

His wedding day is officially over.

He’s been married for 5 hours and 41 minutes.

His wife has been dead for 8 minutes.

Herb walks to the sweet phone, picks up the receiver.

His voice when he speaks to front desk, carries perfect panic.