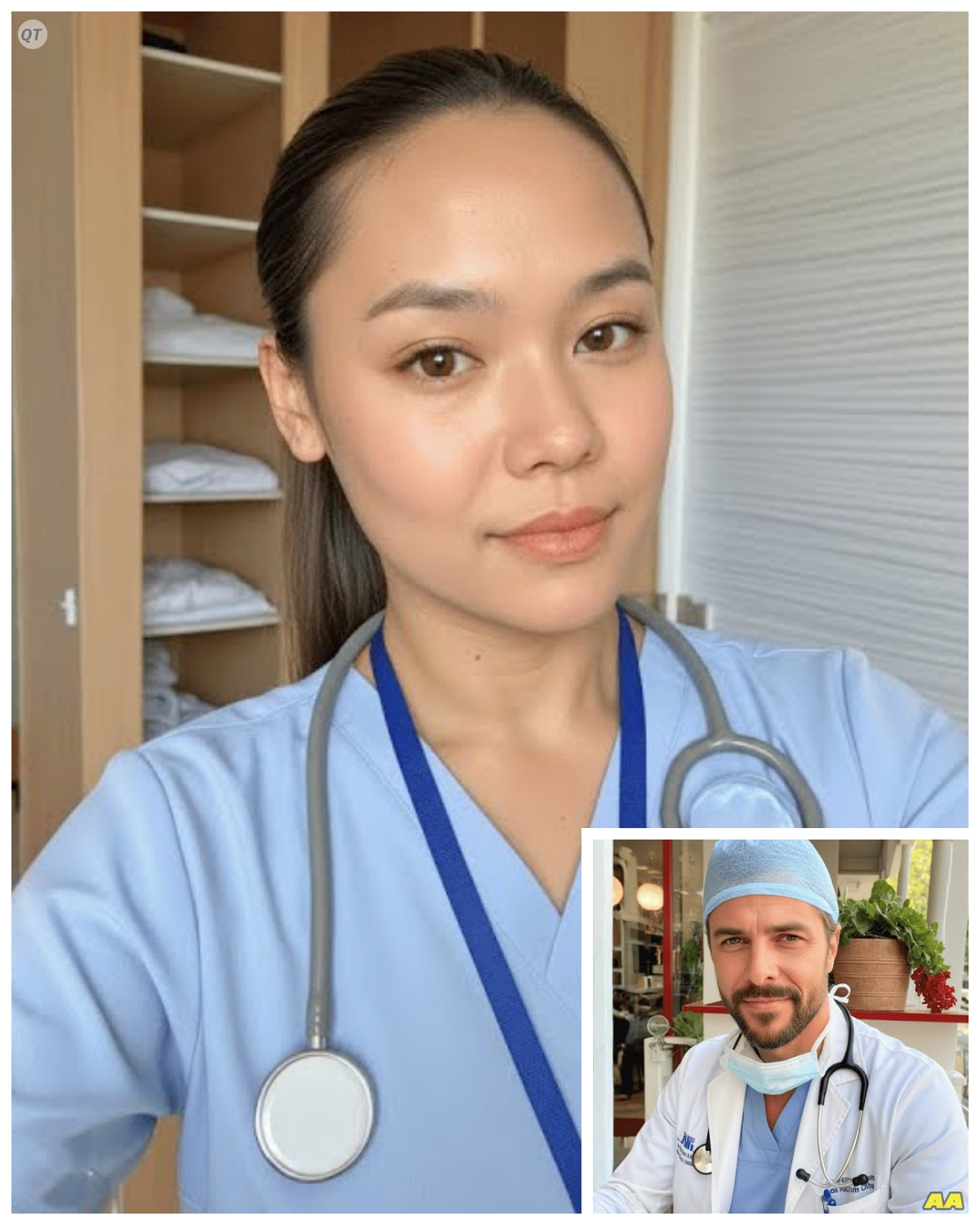

The security camera outside supply room 3B at Mercy Heights Medical Center captured two separate entries on the night of November 14th, 2024.

At 11:43 p.m., Dr.

Ethan Wallace’s badge accessed the locked door.

90 seconds later, Nora Reyes followed.

Only one of them would walk out alive.

By morning, the hospital would call it a tragic accident.

But the blood on the sterile tile floor told a different story entirely.

This isn’t a tale of passion gone wrong.

This is a story about power wielded as a weapon, about a woman trapped between poverty and survival, and about how easily institutions protect predators while discarding victims.

What happened in that supply room didn’t begin with violence.

It began months earlier with a single mistake and a surgeon who saw opportunity in vulnerability.

Dr.Ethan Wallace was the kind of man whose photograph hung in the hospital’s main corridor alongside the words excellence in cardiac care.

At 42 years old, he had spent 15 years building Mercy Heights Medical Cent’s cardiovascular program into one of the most respected in the Midwest.

His credentials read like a medical fairy tale.

graduate of Northwestern Medical School, where he finished top of his class.

47 published peer-reviewed articles: Innovations in minimally invasive heart surgery that had been adopted by hospitals across the country.

Patients called him a miracle worker.

The 73-year-old grandmother, who walked out of the hospital 6 weeks after he replaced three of her heart valves, kept his photo on her mantle beside pictures of her grandchildren.

The high school football player, whose congenital heart defect should have ended his athletic career, credited Dr.

Wallace with giving him a future.

Local news stations featured him in their medical hero segments, and the hospital’s charity gala each year raised hundreds of thousands of dollars thanks largely to his willingness to share dramatic surgical stories that left donors reaching for their checkbooks.

But the public Ethan Wallace and the private Ethan Wallace existed in two different worlds.

At home in the Lakewood Hills subdivision, in a house valued at $3.

2 $2 million.

He played the role of devoted husband to Victoria, a corporate attorney whose career ambitions matched his own.

Their children, Madison and Blake, attended the district’s most prestigious private academy.

Ethan coached Blake’s little league team on Sunday afternoons when he wasn’t on call.

And neighbors who saw him grilling burgers in his backyard or washing his Mercedes in the driveway thought they knew him.

They didn’t know about the three HR complaints filed against him over the past 8 years.

all settled quietly with non-disclosure agreements and monetary payments that never made it into his personnel file.

They didn’t know how he looked at young female staff members when he thought no one was watching.

They didn’t know that his mentorship of promising young nurses and medical students sometimes crossed lines that should never be approached, let alone violated.

The hospital knew, of course, but Dr.

Ethan Wallace brought in over $120 million annually to Mercy Heights through his surgical program.

Men who generate that kind of revenue are forgiven many sins.

When complaints surfaced, they were handled discreetly.

The complainants were offered transfers to different departments or generous severance packages in exchange for silence.

The pattern continued because the cost of protecting him was always less than the cost of losing him.

Nora Reyes understood nothing of this history when she arrived at Mercy Heights in 2020.

She knew only that America represented hope, that her salary as an ICU nurse could support her entire family back in the Philippines, and that if she worked hard enough and stayed quiet enough, she might finally give her mother and siblings the security that had eluded them since Typhoon Hayan took her father in 2013.

She had grown up in Taclobin City in Ley province, the youngest of five children in a family that measured wealth in whether they ate rice with every meal or only twice a day.

Her father had been a fisherman.

Her mother a market vendor who rose at 4 each morning to arrange mangoes and dried fish on a wooden table in the public market.

When the typhoon came, it took their father and their home and most of their hope.

Norah’s mother never fully recovered from watching her husband’s boat fail to return to shore.

She aged a decade in a single year.

Norah had always been the smart one, the one who stayed up late reading by candle light, who memorized lessons other children forgot by morning.

Her teachers at the public school told her mother she was special, that she should attend university.

But university required money the family didn’t have.

When a wealthy aunt offered to pay for nursing school, Nora accepted with the understanding that this wasn’t charity, but investment.

She would be expected to repay it by supporting the family once she found work.

She graduated from the University of Sto.

Tomtomas in 2018 with honors and immediately began applying to positions overseas.

The Philippines produced excellent nurses, but the country couldn’t offer salaries sufficient to support aging parents and younger siblings still in school.

America paid five times what she could earn at home.

When the medical staffing agency contacted her about a position at Mercy Heights Medical Center in Chicago, she didn’t hesitate.

The H1B work visa they offered was her family’s salvation.

The reality of life in America proved harder than the brochure suggested.

Nora arrived in Chicago in February 2020, just weeks before the pandemic would transform health care into a war zone, and found herself working 12-hour night shifts in the cardiovascular ICU.

The work itself didn’t frighten her.

She had strong hands and a steady temperament, and patients responded to her gentle manner and genuine care, but the isolation was crushing.

She lived in a studio apartment in South Lakewood, a neighborhood where she could afford the rent, but rarely saw anyone who looked like her or spoke to Galog.

She ate meals alone, slept during the day when the rest of the world was awake, and video called her family every Sunday to hear about her mother’s health and her younger sister’s progress in college.

Every month, she sent home $1,200, nearly 60% of her paycheck.

The money covered her mother’s medication for diabetes and high blood pressure.

her sister’s tuition and helped support the grandchildren her older siblings were raising.

Back in Techlobin, the family called Nora their angel.

In Chicago, she wore the same four sets of scrubs that she washed by hand in her bathroom sink because buying more seemed wasteful when that money could go to her family instead.

She couldn’t afford to lose this job.

She couldn’t afford to make enemies.

She couldn’t afford to say no when powerful people made requests.

Mercy Heights Medical Center loomed over the Southside like a monument to modern medicine.

847 beds spread across 12 floors of glass and steel.

The cardiovascular unit occupied the seventh floor where the most critical cardiac patients received roundthe-clock monitoring from nurses like Nora, who had been specially trained to recognize the subtle signs that a heart was failing before the monitors could catch it.

It was highstakes medicine, the kind where small mistakes could cascade into fatal consequences.

And the pressure created a rigid hierarchy that everyone understood, even if no one discussed it openly.

Surgeons stood at the apex of this hierarchy, god-like figures in white coats whose decisions determined who lived and who died.

Below them came the attending physicians, then the residents and interns, then the nurses, and finally the support staff who emptied bed pans and mopped floors.

This structure wasn’t unique to Mercy Heights.

It existed in every hospital in America, a cast system dressed up in the language of medical expertise, but reinforced by something more primitive, power.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace understood power.

He knew that his position on the hospital board gave him influence over hiring and firing decisions.

He knew that his reputation brought prestige to the institution and that prestige translated into funding and grants and the ability to attract the best medical students.

He knew that nurses needed positive evaluations from the doctors they worked with and that a single negative comment in a personnel file could derail a career.

Most importantly, he knew which nurses were vulnerable, which ones couldn’t afford to complain, which ones had something to lose that was more valuable than their dignity.

Supply room 3B was located between two mechanical rooms on the seventh floor, a 12 by 15 ft space stocked with four fluids, catheters, sterile equipment, and medication preparation supplies.

Hospital staff accessed it with their security badges, and a camera pointed at the entrance recorded who came and went, but the camera didn’t capture what happened inside, and the mechanical rooms on either side created enough ambient noise that conversations held in the supply room remained private.

Over the years, it had become known among staff as the place where difficult conversations happened, where doctors dressed down nurses who had made errors, where personnel matters were discussed away from patients and families.

It had also become something else, a place where people disappeared for minutes at a time and emerged looking shaken or flushed or angry, and no one asked questions because asking questions meant involvement, and involvement meant consequences.

The fateful charting error occurred on October 18th, 2023 at 3:42 in the morning.

Nora had been on hour nine of her shift managing three critical patients in the cardiovascular ICU.

One of them was Marcus Chen, a 67year-old man recovering from coronary artery bypass grafting surgery.

Hospital protocol required that nurses check and document vital signs every 2 hours for postsurgical patients.

Nora had performed the 2 a.

m.

vital check, confirmed that Mr.

Chen’s heart rate and blood pressure were stable, adjusted his four fluids accordingly, and then been pulled away to assist with an emergency in the next room before she could log the vital signs into the computer system.

She meant to go back and complete the documentation.

She always completed her documentation, but the emergency took 40 minutes, and by the time she returned to her station, the specific details of Mr.

Chen’s vitals had begun to blur with the dozens of other data points she had collected that night.

She made a note on paper to complete a late entry during her next break, then got pulled into another patient crisis, and the note got buried under other papers.

And by 6:00 a.

m.

, when her shift ended, and she dragged herself to the parking lot with exhaustion, making her vision blur, she had forgotten entirely.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace began his rounds at 6:00 a.

m.

reviewing charts and checking on the post-operative patients before his first surgery at 8.

He spotted the missing documentation immediately.

A meticulous surgeon develops an eye for gaps in the medical record for the spaces where information should exist but doesn’t.

Any attending physician would have handled this the same way.

Mention it to the charge nurse who would then follow up with Nora to complete a late entry with an explanation.

It was a minor error, the kind that happened occasionally in the chaos of a busy ICU.

And standard protocol existed to correct it without drama.

But Ethan Wallace didn’t follow standard protocol.

He saw something else in that missing vital sign documentation.

An opportunity.

He found Nora in the medication preparation room just as she was gathering her belongings to leave.

The room was small, barely large enough for two people with a counter along one wall where nurses drew up medications and a refrigerator that hummed loudly enough to muffle quiet conversation.

Fluorescent lights buzzed overhead, casting everything in the harsh blue white glow that made everyone look slightly ill.

“Nurse Reyes,” he said, and she turned, surprised to see the chief of cardiovascular surgery addressing her directly.

In 6 months of working at Mercy Heights, she had assisted with his patients dozens of times, but he had never learned her name, had never made eye contact with her for more than the seconds required to issue instructions during rounds.

Now he was looking at her with an expression she couldn’t quite read.

Something between concern and something else.

Yes, Dr.

Wallace.

She kept her voice respectful, differential.

The way she had been taught to address authority figures both in nursing school and in her childhood home.

He moved into the room and let the door swing closed behind him.

The click of the latch seemed louder than it should have been.

We need to talk about Marcus Chen’s chart.

The 2 a.

m.

vital signs aren’t documented.

Her stomach dropped.

I did the check.

I just forgot to log it.

I can complete a late entry right now.

That’s not how the medical board will see it.

His voice was calm, almost kind, but there was something underneath the kindness that made the hair on the back of her neck stand up.

You know what happens to nurses who falsify medical records? It’s not just a disciplinary issue.

It’s a legal issue.

The nursing board gets involved.

Immigration gets involved.

The word immigration hit her like cold water.

I didn’t falsify anything.

I did the check.

I just didn’t document it right away.

That’s different, is it? He crossed his arms, blocking the door with his body, even though there was technically room for her to squeeze past if she tried.

From a legal standpoint, there’s no difference between forgetting to document and never performing the check in the first place.

Both scenarios show the same thing in the chart, missing data.

And with your visa status, any question about your competence or your honesty becomes an immigration matter.

You understand that, right? She understood.

She understood that her H1B visa was tied to her employment, that losing her job meant losing her legal right to stay in the country, that immigration enforcement didn’t distinguish between getting fired for incompetence and getting fired for any other reason.

She understood that deportation would mean returning to the Philippines where she couldn’t earn enough to support her family, where her mother’s medication would become unaffordable, where her sister would have to drop out of college.

She understood that everything she had sacrificed for, everything she had endured could disappear because of one misdocumentation entry at 3:00 in the morning.

“I can fix this,” he said.

And now, his voice was definitely kind, the voice of someone offering help.

I’ll backdate my progress note.

Say that I verbally confirmed the vital signs with you during rounds.

That creates a record that the check was performed and you can complete your documentation as a late entry referencing my note.

Problem solved.

Relief flooded through her followed immediately by confusion.

Why would the chief of cardiovascular surgery go out of his way to help a staff nurse he barely knew? Thank you, Dr.

Wallace.

I really appreciate, but you understand, he interrupted.

and the kindness in his voice took on an edge.

That when someone helps you like this, you owe them.

People who help me, I help back.

People who don’t.

He let the sentence trail off unfinished.

The threat implicit in what wasn’t said.

So, we’re clear.

You owe me now.

It wasn’t a question.

It was a statement of fact, a debt incurred, a power dynamic established.

Norah nodded because what else could she do? Her nursing training had taught her to assess situations quickly and respond appropriately.

This situation was clear.

Refuse his help and face possible termination and deportation or accept his help and incur some undefined future obligation.

It wasn’t really a choice at all.

“Thank you,” she said again, and her voice sounded small even to her own ears.

“Good girl,” he said, and smiled and left the medication room.

Nora stood there for a long moment after he was gone, staring at her reflection in the glass door of the medication refrigerator.

She looked tired.

She looked scared.

She looked like someone who had just made a terrible mistake, but couldn’t quite identify what it was.

She told herself it was nothing, that he was just being kind in a somewhat awkward way, that powerful men sometimes came across as intimidating even when they meant well.

She told herself she would work harder, be more careful with her charting, make sure she never gave him or anyone else reason to question her competence.

She told herself that if she kept her head down and did her job perfectly, he would forget about her and this debt would fade into nothing.

She was wrong about all of it.

The pattern established itself slowly, so gradually that Norah didn’t recognize it as a pattern until she was already caught in it.

November 2023 began normally enough.

She worked her night shifts, took care of her patients, sent money home every Friday, and tried not to think too much about the brief encounter with Dr.

Wallace in the medication room.

He had filed his backdated note.

She had completed her late entry, and the missing documentation was resolved without incident.

She hoped that was the end of it.

The first text message arrived on November 8th at 11:37 p.

m.

Halfway through her shift, her phone buzzed in her pocket while she was adjusting in four drip for a patient recovering from valve replacement surgery and she ignored it until she could step away.

When she finally checked, she saw an unfamiliar number and a brief message.

Can you stay late to assist with posttop checks on the cardiac patients? Want to make sure everything is covered.

Ew, A W.

Ethan Wallace.

Somehow he had gotten her personal cell phone number, though she had never given it to him.

Hospital staff directories included employee contact information.

She reminded herself.

There was nothing inappropriate about a doctor texting a nurse about patient care.

She responded that she could stay an extra hour if needed, and he sent back a thumbs up emoji.

The shift proceeded without incident, and Dr.

Wallace never called on her for the additional assistance.

She wondered if he had forgotten or if the situation had resolved itself.

The next text came 3 days later at 2:15 in the morning.

Need to discuss patient care protocols.

Can you meet me in my office after your shift? This message felt different, less concrete.

What protocols? Which patient? But questioning a surgeon’s request felt dangerous, especially given the debt she owed him.

So, she agreed.

At 7:00 a.

m.

, exhausted and wanting nothing more than to go home and sleep, she made her way to the administrative wing where the senior physicians kept their offices.

Dr.

Wallace’s office looked exactly as she expected, degrees and certifications covering one wall, awards and plaques on another, photographs of him with famous patients and politicians scattered across his desk and credenza.

He gestured for her to sit in the leather chair across from his massive oak desk, and she perched on the edge of it, her body language communicating her desire to make this meeting brief.

“You look tired,” he said, studying her face with an intensity that made her uncomfortable.

“You’re working too hard.

” “I’m fine, Dr.

Wallace.

You wanted to discuss protocols, right?” He leaned back in his chair, steepling his fingers.

“I’ve been observing your work.

You’re good.

Very thorough.

better than most of the nurses on the floor.

“Thank you,” she waited for him to continue to explain the actual purpose of this meeting.

“You’re far from home,” he said instead.

“The Philippines, right, Techloin? That must be lonely being so far from family.

How did he know she was from Techlobin specifically?” Had he looked up her personnel file? I video chat with them every week.

It’s not so bad.

Still, that’s a lot of pressure.

Supporting a family on a nurse’s salary, sending money home every month.

What is it? Half your paycheck.

He said it casually, but the implication was clear.

He had researched her, knew her financial situation, understood exactly how precarious her position was.

I manage fine.

Her voice came out more defensive than she intended.

I’m sure you do.

I’m just saying if you ever needed help, needed someone to advocate for you, I’m on the hospital board.

I have influence over salary decisions, overtime assignments, that sort of thing.

Could make your life easier.

He paused, watching her reaction, or harder, I suppose, depending.

There it was again that unfinished threat, the offer of help with the implicit suggestion that refusing the help would have consequences.

Norah’s heart rate picked up, her nurse’s instincts automatically assessing her own vital signs.

Elevated heart rate, muscle tension, hypervigilance.

Her body recognized a threat, even if her conscious mind was still trying to rationalize this conversation as normal.

I appreciate that, Dr.

Wallace.

Is there anything specific about patient protocols you wanted to discuss? He smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes.

Not today.

Just wanted to check in, make sure you’re settling in well.

You can go get some rest.

She stood, moving toward the door quickly, and his voice stopped her.

Oh, and Nora.

You can call me Ethan when we’re alone.

We’re colleagues after all.

Colleagues, as if a staff nurse and the chief of cardiovascular surgery existed on the same plane, as if the power differential between them didn’t make that suggestion absurd and inappropriate.

She mumbled something that might have been agreement or acknowledgement and fled to her car.

The text messages continued through November and into December, arriving at odd hours, 11:00 p.

m.

, 2:00 a.

m.

, 5 in the morning.

Sometimes they contained actual work rellated questions.

More often they were personal observations.

You look tired today.

Make sure you’re taking care of yourself.

I’m watching.

Saw you in the cafeteria.

You should eat more.

You’re too thin.

Working another double shift.

Don’t burn yourself out.

You’re too valuable.

Each message created a small jolt of anxiety.

She started checking her phone compulsively, dreading the sight of his number.

She became hyper aware of his presence on the floor, tracking his movements during rounds so she could avoid being alone with him.

But Mercy Heights wasn’t that large, and the cardiovascular unit was his territory.

Avoiding him completely was impossible.

December brought the office visits.

He would page her during her shift, asking her to come to his office to review a patients care plan or discuss a medication order.

These meetings always started with legitimate medical topics before sliding into personal territory.

He asked about her family, her life in the Philippines, her immigration status.

He positioned himself as sympathetic, understanding, the one person in the hospital who truly saw her as a human being rather than just another nurse.

The American health care system isn’t kind to immigrants, he told her during one of these meetings.

I’ve seen good nurses get chewed up and spit out because they didn’t have anyone protecting them.

You’re lucky I’m looking out for you.

Lucky.

The word made her stomach turn, but she smiled and thanked him because what else could she do? She had been raised to respect authority, to defer to people in power, to never cause trouble.

Her Catholic upbringing taught her to be grateful, to trust that people in positions of leadership had good intentions.

But the way his hand lingered on her shoulder when she stood to leave, the way his eyes traveled down her body when he thought she wasn’t looking, the way he stood too close and spoke too softly, these things contradicted the kindness he claimed to be showing.

In January, the encounters escalated.

He began finding reasons to be wherever she was.

the supply rooms, the medication preparation areas, the empty corridors at the end of the floor where staff went to catch a moment of quiet.

Other nurses noticed.

Dr.

Wallace seems to favor you.

One colleague commented in the break room.

Must be nice having the boss looking out for you.

The comment was edged with something that might have been jealousy or might have been warning.

Norah wanted to explain that she didn’t want his attention, that his favor felt more like surveillance than support.

But how could she articulate that without sounding paranoid or ungrateful? Everyone else seemed to interpret his interest as mentorship, as the natural result of her being a conscientious nurse who had caught the eye of a demanding but fair surgeon.

No one else seemed to see the predation underneath the professional veneer.

On Valentine’s Day, he cornered her in supply room 3B at 10:30 p.

m.

She had gone there to restock her medication cart for the night shift, and he appeared behind her so quietly that she didn’t know he was there until she turned and found him blocking the door.

Her heart hammered against her ribs.

“I got my wife flowers today,” he said conversationally, as if they were having a normal interaction and not standing in a 12×5 ft room with no witnesses and a locked door.

duty.

You know, 20 years of marriage, you do what’s expected.

But I kept thinking about you instead.

Dr.

Wallace, I need to get back to my patients.

She moved toward the door, but he didn’t step aside.

Do you know what it’s like? He continued as if she hadn’t spoken.

To be married to someone who doesn’t see you anymore, who’s so focused on her own career that you’re basically roommates.

Victoria and I haven’t been intimate in months, maybe longer.

I lose track.

Horror washed over Nora.

This was crossing a line so egregious that even her trained deference to authority couldn’t make her rationalize it away.

I really need to go.

I think about you, he said and stepped closer.

The way you move through the unit so careful with the patients, the way you look in those scrubs.

I think about what you look like out of them.

Stop.

The word came out as barely a whisper.

You owe me.

Remember that charting error could have ended your career, gotten you deported.

I saved you and now I’m telling you what I want.

He reached out and touched her face and she flinched away.

What’s wrong? Don’t be like that.

This isn’t appropriate.

Her voice was shaking.

Now you’re married.

I’m your employee.

This is This is what his voice hardened.

Harassment.

You want to file a complaint? Go ahead.

Let’s see how that works out for you.

You think HR is going to side with an immigrant nurse on a work visa against the chief of cardiovascular surgery who brings in over $und00 million to this hospital? You think they’ll believe that I, a married father of two with an impeccable reputation, was hitting on you? Or do you think they’ll believe that you misinterpreted professional mentorship as something inappropriate because you don’t understand American workplace culture? Every word was calculated to paralyze her with fear, and it worked.

She stood frozen as he leaned in and pressed his mouth against hers.

His lips were cold and tasted like coffee.

She kept her mouth closed, her body rigid, and after a moment, he pulled back.

See, that wasn’t so bad.

He smiled at her, and the smile was worse than the kiss because it was so normal, so casual, as if he had just done something sweet and romantic instead of something that made her feel like she was drowning.

We’ll take this slow.

I’m a patient man.

But remember, Nora, you owe me your job.

your visa, your family’s survival.

This is appropriate.

This is just you paying back what you owe.

” He left the supply room and she stayed there for 20 minutes afterward, her back pressed against the metal shelving, her breath coming in short gasps that sounded too loud in the small space.

She wanted to cry, but couldn’t afford to let herself fall apart.

She had seven more hours left on her shift, three critical patients who depended on her, and a family half a world away who depended on the paycheck she earned by enduring whatever this was.

When she finally returned to the floor, she washed her face in the staff bathroom, reapplied her lip balm, and smiled at the next family member who asked her how their father was doing after his bypass surgery.

She performed her job perfectly mechanically, while some part of her mind screamed that she needed to report what had happened, that this was assault, that no job was worth this.

But another part of her mind, the part trained by poverty and immigration procarity and family obligation, calculated the cost of reporting.

She would lose her job.

The hospital would side with Dr.

Wallace.

Her visa would be terminated.

She would be deported.

Her mother’s medication would become unaffordable.

Her sister would drop out of college.

The extended family that depended on the remittances she sent would struggle.

All of that consequence for what? A forced kiss that lasted 5 seconds.

Who would believe her? Who would care? She went home at 7:00 a.

m.

and stood in the shower until the water ran cold, scrubbing her mouth until her lips felt raw.

Then she crawled into bed and stared at the ceiling, telling herself that maybe it was over, that maybe he had satisfied whatever impulse had driven him to corner her, that maybe tomorrow would be normal again.

She was wrong about that, too.

The assaults escalated through February and March.

He began paging her to supply room 3B during night shifts when the floor was understaffed and no one would notice a nurse disappearing for 10 or 15 minutes.

Each time, he pushed further.

A forced kiss became groping.

groping became him pressing her against the shelving and grinding against her while she stood motionless, dissociating, staring at the inventory labels and counting supplies in her head to escape what was happening to her body.

“You’re so tense,” he would say, as if her fear was a personality flaw rather than a reasonable response to assault.

“Just relax.

This is good for both of us.

You need this as much as I do.

” On March 5th, he raped her for the first time.

The attack in supply room 3B on March 5th, 2024 lasted 8 minutes, according to the badge access logs.

Norah’s mind separated from her body during those minutes.

Floating somewhere near the ceiling while Dr.

Ethan Wallace forced himself inside her on the cold tile floor.

She counted ceiling tiles 16.

She cataloged the boxes of normal saline on the shelf.

12 bags per box.

She noted the crack in the floor tile beneath her for inches long, running diagonally.

These details filled her consciousness, protecting her from a reality that would shatter her completely.

When he finished, he stood and adjusted his clothing with the same methodical movements he used when removing surgical gloves.

Clean yourself up.

Get back to work.

And Nora, don’t do anything stupid.

She didn’t move for 3 minutes after he left.

When she finally stood, there was blood on her thighs.

She cleaned herself with paper towels, buried them deep in the biohazard container, and spent 30 minutes in the staff bathroom, forcing her breathing back to normal.

She had 4 hours left on her shift.

Her patients needed her.

She couldn’t fall apart.

She called in sick the next day, her first absence in 4 years at Mercy Heights.

She spent 36 hours on her bathroom floor, unable to make it to her bed.

She tried to convince herself to go to the police, but the obstacles were insurmountable.

No evidence, no witnesses, his word against hers.

An immigrant nurse versus a prominent surgeon.

Even if they believed her, the investigation would cost her job, her visa, her family’s survival.

The assaults continued through March.

On March 12th, he was more violent, leaving bruises on her arms she covered with long sleeves.

“You’re mine now.

Remember that?” he whispered afterward.

By mid-March, she had lost 8 lb.

Insomnia consumed her days.

She briefly considered suicide, standing on her third floor balcony, calculating whether the height was sufficient.

But suicide was a mortal sin, and more pragmatically, her death would leave her family with nothing.

On March 20th at 3:00 a.

m.

, she composed an email to immigration attorney Elena Vasquez.

She typed the entire story, the coercion, the visa threats, the rapes, her need to understand her rights.

She read it seven times, finger hovering over send for 20 minutes.

Then she saved it as a draft and closed her laptop.

Even seeking legal advice felt dangerous.

April brought the discovery.

Her period, always regular, was 2 weeks late.

The nausea that started April 10th, the tender breasts, the exhaustion, symptoms too familiar to dismiss.

On April 15th, she bought a pregnancy test at a distant drugstore, paying cash.

She took it in the hospital bathroom during her shift.

Two pink lines appeared immediately, clear, undeniable.

She sat on the toilet holding the positive test.

Her mind blank before the implications crashed over her, pregnant with her rapist child.

Her Catholic upbringing said abortion was murder, but carrying this baby felt impossible.

How would she work through pregnancy? How would she hide it? How would she afford care? How could she look at a baby who reminded her of violation? The free clinic in South Lakewood confirmed it.

6 weeks pregnant.

The counselor gave her pamphlets on options.

Abortion prices ranged from $600 to $1,200.

She had $217 after sending money home and paying rent.

No friends to borrow from.

No way to ask family without explaining.

trapped again by biology, poverty, and religious guilt.

On April 22nd, she texted Dr.

Wallace.

We need to talk.

It’s urgent.

His reply: Supply room 3B, 11 p.

m.

The location was deliberate cruelty, forcing her back to the scene of her assaults.

She entered at 11 p.

m.

exactly.

He was already inside checking his phone.

What’s so urgent? I’m pregnant.

5 seconds of silence.

Then his face shifted to cold calculation.

Are you sure it’s mine? You know it is.

This is a problem.

Not I’m sorry or are you okay? Just this is a problem.

You need to get rid of it.

He demanded.

I have a family career.

This cannot get out.

I’ll give you money for a clinic.

Indiana.

No questions asked.

I don’t know if I can do that.

This is a life.

It’s a cluster of cells.

He said coldly.

Don’t be stupid.

You think you can raise a baby on your salary while supporting your family? This is not time for religious dramatics.

Handle it this week.

Problem solved.

I need time.

You don’t have time.

He stepped closer.

Here’s what happens if you don’t take care of this.

I report the charting error.

I file complaints with the nursing board about falsified records.

I contact immigration about your competence and mental stability.

I tell everyone you seduced me that you’re trying to trap me.

I destroy you completely or you handle this quietly.

Choose fast.

Over the following weeks, the pressure intensified.

Daily texts.

Have you handled it yet? The messages became threats.

I can get you pills.

Take them.

It’s over.

Don’t make me do something we’ll both regret.

By July, she was 16 weeks along and showing.

She wore baggy scrubs, but her small frame made concealment difficult.

Dr.

Wallace noticed during rounds rage flashing across his face.

That afternoon, he cornered her in the medication room.

You’re showing.

I couldn’t do it.

I tried.

You couldn’t or you wouldn’t.

Do you understand what you’re doing to me? You’re walking around with evidence like it’s a trophy.

It’s not evidence of what we’ve been doing.

It’s evidence of what you did to me.

The words came out stronger than intended.

He grabbed her arm, bruising her flesh.

Don’t you dare rewrite this.

You could have said no.

You could have walked away.

I said no.

I said no and you didn’t care.

She was crying.

You raped me.

You used my visa against me.

You raped me.

He released her.

His face contemptuous.

No one will believe you.

You’re a desperate immigrant.

I’m a respected surgeon.

Your word against mine.

We both know how that ends.

She knew he was right.

But something had shifted.

She had already lost everything.

dignity, safety, belief that compliance would protect her.

What was left to lose? I’ve been documenting everything, she said, watching his confidence falter.

Dates, times, what you said, what you did.

I have emails to attorneys.

I have evidence.

It was only partially true.

Scattered journal entries and unscent email, but he didn’t know that.

For the first time, she saw fear in his eyes.

You’re bluffing.

Try me.

The threat hung between them before he left.

Norah stayed in the medication room, heart pounding, wondering if she had just saved herself or signed her death warrant.

November 13th, 2024.

Norah woke at 2 p.

m.

, her 20we pregnant body, making rest impossible.

She sat at her kitchen table staring at her journal, then wrote what she suspected might be her final entry.

Last entry.

He wants to meet tonight.

I think he’s going to hurt me.

his text yesterday.

This ends now.

Thursday night, supply room 3B, 11:45 p.

m.

Last time I asked nicely.

If something happens to me, Dr.

Ethan Wallace murdered me.

He raped me starting in March.

Used my visa to threaten me.

This baby is his.

Conceived through violence.

He demanded I abort it.

I refused.

Now I think he’s going to kill me.

Whoever finds this, please believe me.

Don’t let them call it an accident.

She hid the journal under her mattress, then texted her mother, “I love you.

Take care of yourself.

” A simple goodbye her mother wouldn’t recognize as final.

At Mercy Heights, she took report and settled into her shift.

At 11:30 p.

m.

, his text arrived, “Don’t be late.

” Security footage at 11:43 p.

m.

showed Dr.

Wallace’s badge accessing supply room 3B.

He entered quickly, glancing down the hallway.

Inside he paced mind racing through scenarios.

The pregnancy was too far along for medication abortion.

She was refusing anyway.

She claimed to have documentation.

As long as she was alive, she was an existential threat to his marriage, career, reputation, freedom.

His lawyer’s words echoed.

In this climate, an accusation alone destroys your career.

Even without conviction, your life ends.

If she was gone, if she couldn’t testify, her accusations died with her.

At 11:44 p.

m.

, Norah’s badge swiped through.

Camera captured her approach.

Floral scrubs over her pregnant belly, hand resting protectively on her abdomen, hesitation in her steps.

She paused at the door, took a breath, entered.

“You came,” Ethan said from across the room.

“You didn’t give me a choice.

” She stayed near the door, shoulders hunched defensively.

Seven months, Nora.

Seven months to handle this quietly.

You’re 20 weeks pregnant.

Creating a time bomb that destroys us both.

I’ll disappear.

Quit.

Move away.

Raise the baby alone.

You never see me again.

And when you need money and file a paternity suit.

When you get angry and talk to lawyers.

He shook his head.

That’s just delayed detonation.

I’ll sign something.

Anything you want.

Your promises are worthless.

He moved toward her.

The only promise I trust is you not being around to break it.

The threat was explicit.

Norah reached for the door handle, but Ethan lunged, grabbing her wrist.

She stumbled, her hip colliding with a metal cart for fluid boxes toppled to the floor with hollow thuds.

“Let me go.

Not until we settle this.

” He pulled her away from the door, eliminating escape.

“I’m keeping the baby,” she said, defiant despite terror.

You can’t make me do anything anymore.

You should be very afraid.

I can’t make you do anything.

But I can make sure you don’t do anything either.

She understood.

Then she was going to die here.

The clarity brought strange courage.

You’re a monster, a rapist.

Everyone thinks you’re a great man, but you’re nothing.

Weak and pathetic, destroying people to feel powerful.

Rage flashed across his face.

I saved your career, protected you.

This is how you repay me.

You didn’t save me.

You trapped me, used my visa, threatened my family, raped me repeatedly.

Now you want to kill me to erase evidence, but I documented everything.

I have an email to an attorney ready to send.

If you kill me, people will know.

She was bluffing about the email being ready to send, but it worked.

His expression shifted to cold decisiveness.

Where’s your phone? She handed it over.

He scrolled through her email, found the draft to Elena Vasquez, his face darkening.

“This is exactly why you’re a problem,” he pocketed the phone.

Then his hands were around her throat.

The attack was sudden, brutal.

His thumbs pressed into her windpipe with surgical precision.

She clawed at his hands, nails drawing blood.

She tried to scream, but nothing emerged.

Her vision blurred.

She kicked his shins, but he didn’t release.

Her medical training cataloged her own death.

60 seconds to unconsciousness, 3 to four minutes to brain damage.

This is your fault, he hissed.

You made me do this.

All you had to do was get rid of the baby and stay quiet.

Her struggles weakened, her arms dropped, consciousness faded.

The last thing she saw clearly was his face twisted with rage.

Her final thought, “I hope someone finds my journal.

” Ethan held his grip 90 seconds after she went limp, counting like during surgery.

When he released her, she crumpled.

Her head struck a metal shelf bracket, opening a gash that bled immediately.

Her neck was at an unnatural angle.

I stared at nothing.

He stood frozen for 10 seconds.

Then his surgeon’s brain took over.

This was a problem requiring management.

He positioned her body carefully, knocked over morph boxes, created the appearance of a fall.

Nurse reaching for supplies, loses balance, boxes fall on her, hits head on shelf bracket.

The staging was plausible.

He removed his blood spattered white coat, rolled it up, used hand sanitizer on his hands, but the scratches she left were too deep to hide.

At 12:02 a.

m.

, he exited, walking briskly toward the surgeon’s lounge.

He changed scrubs, stuffed the bloody coat in a biohazard bag for incineration, washed thoroughly.

He examined his reflection, composed professional, practiced his expression, concerned but not guilty, then headed back to the cardiovascular unit.

At 12:04 a.

m.

, he asked the charge nurse, Maria Santos.

Have you seen nurse Reyes? Maria paged her.

No answer.

Maybe she’s with a patient.

I’ll check the supply rooms, Ethan offered.

He checked 3A first, calling her name, then 3B.

He opened the door and his reaction was perfect.

Sharp intake of breath.

Step backward.

Oh my god.

Call a code.

Get security.

Staff came running.

The code blue team arrived, but Dr.

Patel pronounced her dead immediately.

Gone at least 15 minutes.

Ethan stood outside the room, face shocked and grieving.

She was one of our best nurses.

This is terrible.

He watched them zip Nora Reyes into a body bag and will her away.

He felt relief mixed with the first whisper of paranoia.

What if she really left evidence? What if someone looked closely enough to see through his staging? He pushed the thought away.

He had been careful.

He had been smart.

He would be fine.

He was wrong.

The official story was crafted within 3 hours of Norah Reyes’s death.

By 3:00 a.

m.

on November 14th, 2024, Mercy Heights Medical Cent’s executive team had assembled in a second floor conference room to perform what they called risk management, but what actually amounted to damage control.

CEO Gerald Hammond sat at the head of the table, flanked by chief of staff Dr.

Pamela Brooks, risk management director Lisa Chun, and hospital legal counsel Robert Martinez.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace had been summoned to provide his account of events.

Walk us through what you know,” Hammond said, his voice carrying the practiced calm of someone who had navigated hospital crisis before.

Ethan sat with his hands folded on the table, his posture conveying exhaustion and grief.

I was checking on post-operative patients around midnight, standard protocol for my complex cases.

I asked the charge nurse to page nurse Reyes because I needed her to verify some vital signs on one of my cabbed patients.

When she didn’t respond, we went looking.

Maria Santos found her in supply room 3B.

“Any idea why she was in there?” Martinez asked, pen poised over his legal pad, probably restocking supplies.

Norah was meticulous, always made sure she had everything she needed before it became an emergency.

Ethan’s voice caught slightly on her name.

A perfect touch of emotion.

She was one of our best nurses.

Lisa Chin pulled up security footage on her laptop.

Badge access shows nurse Reyes entering the supply room at 11:44 p.

m.

No other activity until Maria Santos discovered the body at 12:07 a.

m.

What the footage didn’t show, what no one thought to look for yet was Ethan’s badge access 90 seconds before Norris.

The camera angle captured the door but not the full hallway.

And in the chaos of the emergency response, no one had requested the complete access logs.

They saw what they expected to see.

a nurse entering a supply room alone and a tragic accident that followed.

The medical examiner arrived at 4:00 a.

m.

to perform a preliminary external examination.

Dr.

Kenneth Louu had been the Cook County Medical Examiner for 12 years, long enough to have seen every type of death the city could produce.

He photographed Norah’s body in Situ before it was moved, noting the position, the scattered four supply boxes, the blood pulled under her head from the gash on her scalp.

Looks consistent with a fall, he told the hospital administrator.

Possibly reached for supplies on a high shelf, lost her balance, pulled boxes down, head trauma from the shelf bracket.

I’ll know more after the full autopsy, but Dr.

Louu didn’t perform a full autopsy that morning.

Standard protocol for obvious accidental deaths was external examination only, with full autopsy reserved for suspicious circumstances.

A nurse slipping and falling in a supply room didn’t qualify as suspicious.

The preliminary cause of death was listed as blunt force head trauma.

Manner of death accident.

Norah’s body was transported to the morg and placed in cold storage, awaiting family notification and disposition instructions.

The notification call to the Philippines was handled by hospital administration at 6:00 a.

m.

Chicago time, 8:00 p.

m.

in Taclobin.

Carmen Reyes, Norah’s younger sister, answered the phone at their mother’s house.

The voice on the line was professionally sympathetic, carefully scripted.

I’m calling from Mercy Heights Medical Center in Chicago.

I’m very sorry to inform you that your sister Nora Reyes was involved in a fatal accident at work.

She passed away early this morning.

Carmen’s scream brought their mother running from the kitchen.

The phone dropped, clattered on the floor, and the line went dead.

The hospital administrator made a note in the file.

Family notified appeared to be in shock.

Will follow up regarding body transport and arrangements.

What no one at Mercy Heights knew was that Grace Delgado had been unable to sleep that night.

Grace worked day shift on the cardiovascular unit, occasionally overlapping with Nora during shift changes.

They had never been close.

Norah kept to herself, seemed to carry some private burden that prevented real friendship.

But Grace had noticed things over the past months.

The way Norah flinched when Dr.

Wallace appeared on the floor.

The weight loss that made her scrubs hang loose.

The haunted look in her eyes that Grace recognized from her own past from the year after her uncle had assaulted her at a family gathering when she was 16.

When Grace heard about Norah’s death through the hospital’s internal communication system that morning, something felt wrong.

Norah was careful, almost obsessively so.

She didn’t make mistakes.

She didn’t have accidents.

Grace couldn’t articulate why, but the official story didn’t sit right.

On November 20th, 6 days after the death, Grace made a decision that would crack the case open.

As Norah’s designated emergency contact at the hospital, a formality Norah had completed during onboarding, listing Grace simply because she was the only Filipina nurse, Norah knew well enough to ask.

Grace had been given a key to Norah’s apartment by the building manager.

The family in the Philippines needed someone to pack up Norah’s belongings for shipping, and Grace had volunteered.

The studio apartment in South Lakewood was exactly what Grace expected, neat, sparse, sad.

Norah’s entire life in America fit into one room.

A twin bed with a thin mattress, a small table with two chairs, a hot plate instead of a full stove.

The refrigerator contained basics: rice, eggs, vegetables bought on sale.

The closet held four sets of scrubs, two pairs of jeans, three shirts.

This was the life of someone sending every spare dollar back home, someone surviving rather than living.

Grace began packing methodically, folding clothes into boxes, wrapping the few decorative items Norah owned.

She stripped the bed, and that’s when she found it.

A leatherbound journal tucked under the mattress, hidden, but not hidden enough.

Grace sat on the bare mattress and opened to the first page.

Norah’s handwriting, small and precise, filled the lines.

Grace began reading and didn’t stop until she reached the final entry dated November 13th.

Her hands shook as she processed what she was holding.

This wasn’t an accident.

This was murder.

And the murderer was still walking the halls of Mercy Heights, treating patients, playing the role of berieved colleague, while Norah’s body lay in the morg.

Grace called the police at 9:00 a.

m.

She asked specifically for the homicide division.

Detective Maria Santos, no relation to Maria Santos, the charge nurse, answered the call.

I need to report a murder that was covered up as an accident.

The victim is Nora Reyes.

She worked at Mercy Heights and I have her journal documenting everything.

Detective Santos had been with Chicago PD for 15 years, the last eight in homicide.

She had developed instincts about which calls were legitimate and which were conspiracy theories from griefstricken relatives unable to accept accidental death.

Something in Grace Delgado’s voice told her this was legitimate.

They met at a coffee shop in South Lakewood 2 hours later.

Grace handed over the journal and Detective Santos began reading.

The entries were devastating in their detail.

March 6th.

He forced himself on me tonight in supply room 3B.

I said no.

I cried.

He didn’t care.

April 22nd.

I told him I’m pregnant.

He wants me to abort it.

Says he’ll destroy me if I don’t.

November 13th, last entry.

He wants to meet tonight.

I think he’s going to hurt me.

If something happens, it was Dr.

Ethan Wallace.

He murdered me.

Detective Santos looked up from the journal.

Her expression grim.

You did the right thing calling this in.

This case just became a homicide investigation.

The next 72 hours moved with bureaucratic speed that surprised even seasoned investigators.

Detective Santos obtained a warrant to reopen the investigation, which meant Dr.

Kenneth Louu was ordered to perform the full autopsy that should have been done initially.

On November 22nd, Norah’s body was removed from cold storage and wheeled into the autopsy suite.

Dr.

Lou began with external examination, photographing every inch of Norah’s body under bright surgical lights.

What he found contradicted the accidental death ruling immediately bruising around the throat in a pattern consistent with manual strangulation.

Two thumb-shaped bruises on the front of the neck, finger-shaped bruises on the sides, peticial hemorrhaging in the eyes and on the face, small pinpoint blood vessels that burst from pressure, defensive wounds on her hands, scratches, a broken nail on her right index finger.

Under that broken nail, Dr.

Lou found tissue samples that he carefully collected for DNA analysis.

The internal examination was equally damning.

The hyoid bone in her neck was fractured, a classic sign of strangulation that requires significant force.

Approximately 30 lb of pressure applied for 90 seconds or more.

The head wound that had been listed as cause of death was actually paramotum, occurring at the time of death, but not causing it.

The injury was consistent with her head striking the shelf bracket as she fell or was lowered to the ground, but the actual cause of death was asphixxiation by manual strangulation.

Dr.

Lou’s amended autopsy report was unequivocal.

Cause of death, asphyxiation by manual strangulation.

Manner of death, homicide.

The deedent was manually strangled by another person.

The head wound was incurred paramotum but was not the fatal injury.

Evidence of defensive wounds suggests the victim attempted to fight off her attacker.

The deedant was approximately 20 weeks pregnant at time of death.

Detective Santos received the report on November 23rd and immediately expanded the investigation.

She obtained warrants for hospital security footage, not just the camera outside supply room 3B, but all cameras on the 7th floor for the entire evening of November 13th.

When the IT department delivered the files, she spent 6 hours reviewing every frame.

At time stamp 23 hours, 43 minutes and 12 seconds.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace’s badge access supply room 3B.

The camera captured him in profile surgical scrubs, white coat.

A quick glance down the hallway before entering.

At time stamp 23 hours, 44 minutes, and 37 seconds, Nora Reyes accessed the same room.

Her body language was unmistakable, even in grainy security footage.

Hesitant, fearful, one hand on her pregnant belly.

At time stamp 2 minutes and 14 seconds, Dr.

Wallace exited.

He was carrying something bundled under his arm, his white coat.

His posture was tense, his walk quick but controlled.

His face captured briefly as he turned down the hallway, showed no emotion.

Detective Santos called in FBI behavioral analyst Dr.

Marcus Chun to review the footage.

Dr.

Chun had analyzed hundreds of hours of surveillance footage from crime scenes, and he knew how guilty people moved.

“This man,” he said, pointing to Ethan on the screen, is not discovering a body.

He’s leaving a crime scene.

Look at the way he checks the hallway before entering.

That’s security awareness.

Look at how he’s carrying the coat.

That’s evidence disposal.

Look at his gate when he exits.

That’s controlled panic.

This is a perpetrator, not a witness.

The next warrant targeted Ethan’s phone records.

Cell tower data showed his phone was in the vicinity of supply room 3B from 2340 to 05 on November 14th, perfectly consistent with the badge access times.

More damning were the text messages recovered from the cell service provider servers.

Ethan had been communicating with Nora from a number not listed in his official hospital contact information, a personal phone he thought was untraceable.

The message history painted a clear picture of escalating coercion and threat.

March 15th, you owe me.

Don’t forget that.

May 3rd, handle it or I will handle you.

November 10th, this ends now.

Thursday night, 11:45 p.

m.

Don’t be late.

The prosecution would later argue these texts demonstrated premeditation.

A clear threat followed by murder.

3 days later, Detective Santos obtained another warrant.

This one for Norah’s laptop found in her apartment.

The forensics team recovered the draft email to immigration attorney Elena Vasquez dated November 10th.

Never sent but saved.

The email detailed the sexual coercion, the visa threats, the assaults, the pregnancy, the demands for abortion.

It was a road map of systematic abuse ending in the victim’s fear for her life.

On November 25th, Thanksgiving morning, Detective Santos sat in her office reviewing the evidence, the journal, the autopsy report, the security footage, the text messages, the draft email.

She had enough for an arrest warrant.

She called Assistant States Attorney Jennifer Park, who reviewed the evidence and agreed.

By 400 p.

m.

, a judge had signed the warrant.

The arrest was scheduled for November 27th, early morning to maximize the element of surprise.

The arrest team arrived at the Wallace residence in Lakewood Hills at 7:00 a.

m.

The house was decorated for the holiday season, a wreath on the door, lights along the roof line.

Inside, Ethan was having breakfast with his wife, Victoria, and their two children.

The doorbell rang.

Victoria answered and found six police officers and two detectives on her doorstep.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace.

Detective Santos asked, though she knew exactly who he was from the hospital ID photo in the case file.

Yes, he appeared at the door, coffee mug in hand, his expression shifting from confusion to alarm as he registered the police presence.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace, you’re under arrest for the murder of Nora Reyes.

Detective Santos held up the warrant as two officers moved forward with handcuffs.

You have the right to remain silent.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

Victoria’s coffee mug hit the floor and shattered.

What? There must be a mistake.

Ethan, tell them this is a mistake.

But Ethan said nothing.

His face had gone pale, his surgeon’s composure cracking as the handcuffs clicked around his wrists.

Behind him, his daughter Madison started crying.

His son Blake asked, “Daddy, what’s happening?” The perp walk was captured by news crews who had been tipped off.

standard practice for high-profile arrests.

Ethan in handcuffs, guided into the back of a police cruiser, while cameras flashed and reporters shouted questions.

The footage would be on every news channel within the hour.

Prominent surgeon arrested in Nurse’s murder.

The interrogation at the police station lasted 3 hours, though Ethan said almost nothing.

His attorney, Martin Cho from the prestigious firm Thompson and Associates, arrived within 90 minutes and immediately advised his client to invoke his right to silence.

Ethan sat in the interview room, arms crossed, face blank, while Detective Santos laid out the evidence piece by piece.

We have your badge access entering the supply room 90 seconds before Nora Reyes.

We have autopsy results showing she was manually strangled.

We have defensive wounds on her hands and your DNA under her fingernails.

We have text messages where you threatened her.

We have her journal documenting months of sexual assault.

We have her draft email to an attorney describing how you used her visa status to coersse her.

And we have security footage showing you leaving that supply room carrying your coat, which we believe had blood evidence you needed to dispose of.

Ethan’s only response was to look at his attorney, who said calmly, “My client has nothing to say.

He maintains his innocent.

” The bail hearing took place on November 29th.

Assistant States Attorney Jennifer Park argued strenuously against bail.

The defendant is charged with first-degree murder and fetal homicide.

He murdered a pregnant woman to cover up months of sexual assault.

He has significant financial resources and family connections internationally.

He is a flight risk and a danger to the community.

Defense attorney Martin Cho countered, “Dr.

Wallace is a pillar of the community.

He has saved thousands of lives over his career.

He has no prior criminal record.

He has strong ties to Chicago, his wife, his children, his career.

He’s not going anywhere.

This is a case built on circumstantial evidence and the tragic misunderstanding of a workplace accident.

The judge set bail at $2 million.

Ethan posted it within 6 hours using equity in his home and money from his father, a wealthy businessman in Dubai.

He was released with conditions.

GPS ankle monitor, surrender of passport, no contact with hospital employees, and house arrest except for meetings with his attorney.

The public reaction was immediate and divided.

Social media exploded with hashtags.

#justice for Nora trended globally.

The Filipino community organized protests outside Mercy Heights.

Immigration advocacy groups amplified the case as an example of how visa holders are systematically exploited and abused.

But there was a counternarrative, too.

Innocent until proven guilty.

He saves lives, don’t destroy a man’s career over allegations.

Mercy Heights suspended Ethan without pay and hired an external firm to investigate workplace culture.

The investigation uncovered 14 previous HR complaints against various doctors over the past decade, all settled quietly with non-disclosure agreements and financial payments.

The hospital’s general counsel estimated their civil liability in Norah’s case at 8 to 12 million.

They settled with the Reyes family for 8 million 3 weeks later.

A tacit admission that their systems had failed catastrophically.

Carmen Reyes, Norah’s sister, received the settlement notice via email at their mother’s house in Taclobin.

She sat at the kitchen table where Norah had once done homework by candle light and wept.

$8 million, more money than their family would see in 10 lifetimes.

But it couldn’t bring Norah back.

It couldn’t undo the months of terror her sister had endured.

It couldn’t erase the knowledge that Norah had died alone and afraid, murdered by a man who was supposed to heal people.

Their mother, already ill with diabetes and high blood pressure, suffered a stroke two weeks after learning of Norah’s death.

She survived but never fully recovered.

Spending her remaining days in a chair by the window, staring out at the street where Nora used to walk home from school.

She died 8 months later, and Carmen would always believe it was grief that killed her, not disease.

The trial was scheduled for March 2025, giving both sides time to prepare.

The prosecution’s case was strong, but not perfect.

No eyewitnesses, no confession, and a defendant with resources to hire the best defense money could buy.

The defense strategy was already clear from pre-trial motions.

Attack the victim’s credibility.

Suggest the affair was consensual.

Argue that the death was a tragic accident during an argument.

Claimed the prosecution couldn’t prove intent to kill.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace spent the months before trial under house arrest in his Lakewood Hills home, now empty except for him.

Victoria had filed for divorce in December and moved with the children to her parents house.

His colleagues at Mercy Heights refused to speak to him.

His patients, the ones who had called him a miracle worker, felt betrayed.

The narrative was shifting from respected surgeon to predator in a white coat.

But Ethan maintained his innocence, at least publicly.

In private, he replayed that night in supply room 3B over and over, wondering if he had been careful enough, wondering if the evidence would hold up, wondering if his gamble to silence Norah permanently would ultimately destroy him instead.

The answer would come in March when a jury of 12 would decide whether Dr.

Ethan Wallace was a murderer or a man wrongly accused.

But Detective Maria Santos, reviewing the case files one more time in January, had no doubts.

The evidence was overwhelming.

Justice would be served.

She just hoped it would be enough for Nora Reyes, who had come to America seeking a better life and found only exploitation, violence, and ultimately death at the hands of someone who had sworn an oath to do no harm.

The trial of the state of Illinois versus Dr.

Ethan Wallace began on March 3rd, 2025 in the Cook County Criminal Courthouse.

Judge Patricia Williams presided, a 30-year veteran known for running a tight courtroom and having little patience for theatrics.

The jury had been selected after 2 weeks of voadier, seven women, five men, racially diverse, ranging in age from 26 to 64.

Each had sworn they could evaluate the evidence impartially despite the massive media coverage.

The courtroom was packed beyond capacity.

The first three rows were reserved for media.

Court TV was broadcasting live.

CNN had sent their legal correspondent and true crime podcasters jockeyed for the limited press seats.

Behind them sat members of the Filipino community wearing shirts that read, “Justice for Nora.

” On the opposite side, a smaller group of Ethan’s supporters, former patients, medical colleagues who believed in his innocence, sat in grim solidarity.

Assistant States Attorney Jennifer Park stood to deliver opening statements.

She was 42, Korean-American, with a reputation for meticulous case preparation and devastating cross-examinations.

She had prosecuted 37 murder cases and lost only three.

She approached the jury box, made eye contact with each juror, and began.

Ladies and gentlemen, this case is about power.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace had all of it.

Nora Reyes had none.

He was a citizen with a prestigious career and millions of dollars.

She was on a work visa, sending 60% of her paycheck to her family in the Philippines.

He was the chief of cardiovascular surgery.

She was an ICU nurse whose immigration status was tied to her employment.

He was a man.

She was a woman and he used every single one of those advantages to abuse her, exploit her, and ultimately murder her when she became a threat to his comfortable life.

Park walked to the evidence table and picked up a photograph of Nora, smiling in her nursing scrubs.

Nora Reyes was 26 years old.

She came to America because a nurse’s salary here could support her entire family back home.

Her mother’s medication, her sister’s education, her nieces and nephews.

She worked 12-hour night shifts, lived in a studio apartment, wore the same four pairs of scrubs, and saved every penny.

She was exactly the kind of immigrant we claimed to value.

Hardworking, responsible, contributing to society.

Park set down the photo and picked up the journal.

Dr.

Wallace saw her vulnerability and exploited it.

Starting in October 2023, he systematically coerced her into a sexual relationship using her visa status as a weapon.

When she became pregnant as a result of his assaults, he demanded she abort the baby.

When she refused, he made a decision.

She had to be eliminated.

And on November 14th, 2024, he strangled her to death in supply room 3B at Mercy Heights Medical Center.

The prosecutor spent the next 40 minutes laying out the evidence, the journal entries, the text messages, the security footage, the autopsy results, the DNA evidence.

The defense will try to tell you this was a consensual affair that ended tragically.

But consent obtained through threats is not consent.

It’s coercion.

They’ll try to tell you her death was an accident during an argument, but the medical evidence is clear.

Norah Reyes was manually strangled for over 90 seconds.

That’s not an accident.

That’s murder.

Park returned to the jury box.

By the end of this trial, you will have no doubt that Dr.

Ethan Wallace is a predator who used his position to abuse a vulnerable woman.

And when that woman became a problem he couldn’t control, he killed her.

We will prove permeditation, motive, and opportunity.

We will prove murder, and we will ask you to hold him accountable.

Defense attorney Martin Cho stood for his opening statement.

He was 56, white, with silver hair, and the kind of expensive suit that communicated success.

He had built his career defending wealthy clients accused of serious crimes with a 70% acquitt rate.

He approached the jury with a different demeanor than Park, more conversational, more sympathetic.

Dr.

Ethan Wallace is a healer.

Over 20 years, he has saved more than 2,000 lives.

Parents got to watch their children grow up because of his skill.

Grandparents got to meet grandchildren, husbands, and wives got more years together.

These aren’t abstractions.

These are real people whose lives were preserved by Dr.

Wallace’s dedication to medicine.

Cho gestured toward Ethan, who sat at the defense table in a dark suit, looking appropriately somber but not broken.

The prosecution wants you to believe that this man, this healer, is a monster.

They want you to believe he’s a calculated murderer.

But what they’re actually going to show you is a complicated situation, a tragic relationship between two adults, and an accident that occurred during an argument.

The defense attorney acknowledged the affair directly.

Did Dr.

Wallace have a relationship with Nora Reyes? Yes.

Was it inappropriate given their professional relationship? Yes.

Was it complicated and ultimately destructive? Absolutely.

But inappropriate does not equal criminal.

Complicated does not equal murder.

Cho picked up the autopsy report.

The prosecution will show you medical evidence and claim it proves strangulation, but their own expert will have to admit that the injuries could be consistent with other explanations.

They’ll show you text messages and claim they prove threats.

But context matters, and those messages are far more ambiguous than the prosecution suggests.

He paused for effect.

Most importantly, the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Dr.

Wallace intended to kill Nora Reyes.

Not that an accident occurred, not that an argument turned physical, but that he planned and executed a murder.

They can’t do that because it didn’t happen.

At the end of this trial, I’m confident you’ll find that the only verdict consistent with the evidence and the law is not guilty.

The first week of trial focused on establishing the pattern of abuse.

Grace Delgado testified about finding the journal and immediately recognizing that Norah’s death was not an accident.

I knew something was wrong for months.

The way she looked, the way she acted around Dr.

Wallace.

I should have done more to help her.

Dr.

Sarah Kim, the ICU attending who had observed concerning interactions between Ethan and Nora, testified next.

I saw them in the supply room once in June.

When she came out, she looked terrified.

I didn’t report it because I had no proof and he was on the board.

I failed her.

Her voice broke and Judge Williams called a brief recess.

Marcus Johnson, the security guard, presented the badge access logs, walking the jury through the timeline.

Dr.

Wallace entered supply room 3B at 11:43 p.

m.

Nurse Reyes entered 90 seconds later.

Dr.

Wallace exited at 12:02 a.

m.

The body was discovered at 12:07 a.

m.

The defense tried to suggest the logs could be wrong, but Johnson was unshakable.

These systems are accurate to the second.

They have to be for security purposes.

Week 2 brought the devastating medical evidence.

Dr.

Kenneth Lou, the medical examiner, spent an entire day on the stand.

He displayed autopsy photographs that made several jurors look away.

The cause of death was asphyxiation by manual strangulation.

The hyoid bone was fractured which requires approximately 30 lbs of pressure for over 90 seconds.

The particular hemorrhaging in the eyes and face is diagnostic of strangulation.

The defensive wounds on her hands indicate she fought her attacker.

This was not an accident.

The defense cross-examination focused on trying to create doubt.

Dr.

Blue.

Isn’t it true that some of these injuries could occur if someone fell? The head wound, yes, but not the strangulation injuries.

Those require another person’s hands around the victim’s throat.

Could the hyoid bone break from other trauma? In a car accident or a high impact fall, theoretically, but combined with the other findings, the bruising pattern, the peticial hemorrhaging, the defensive wounds, the only explanation is manual strangulation.

Detective Maria Santos testified about the investigation, walking the jury through each piece of evidence.

When she read excerpts from Norah’s journal, several jurors wiped tears.

March 6th, he forced himself on me tonight.

I said, “No, he didn’t care.

” November 13th.

If something happens to me, Dr.

Ethan Wallace murdered me.

The defense objected strenuously.

Hearsay, your honor.

The defendant has no opportunity to cross-examine the author of these statement.

Judge Williams overruled.

Dying declaration exception applies.

The victim wrote these entries believing she was in mortal danger.

They’re admissible.

The text messages were equally damning.

The prosecution displayed them on a large screen for the jury.

Handle it or I will handle you.

This ends now, Thursday night, 11:45 p.

m.

Don’t be late, Park asked Detective Santos.

In your experience, how would you characterize these messages? Clear threats followed by action.

The defendant threatened the victim, set up a meeting, and she ended up dead.

That’s premeditation.

Week three brought expert testimony.

Dr.

Patricia Morrison, a forensic psychologist, explained coercive control.

When someone uses power imbalances, citizenship status, economic dependency, professional authority to force another person into sexual activity, that’s not a relationship.

That’s systematic abuse.

Victims in these situations can’t just leave because the abuser has engineered circumstances where leaving means losing everything.