Breaking right now, an active scene at the Mirage Royale Casino.

Take a look here tonight at this Las Vegas landmark where beneath the glittering facade, a horror unfolds that will shock the international community.

A 28-year-old Filipina cocktail waitress carries another round of bourbon to men who will never remember her face.

Her name is Soladad Cruz, and for three years, she has existed in the margins of Las Vegas luxury.

A perpetual smile painted across her face as hands graze her waist, as cigar smoke burns her lungs, as lonely men confess their sins between whiskey rounds.

But Soladad sees what others choose to ignore.

The Mirage Royale Casino exists in perpetual midnight.

No clocks on the walls, no windows to remind patrons that outside these gold-plated doors, the sun rises and sets on people with normal lives.

Inside, time is measured in chip stacks and cocktail orders, and the mechanical symphony of slot machines that never stop singing their siren song of almost wealth.

Solidad Cruz is 5’3, black hair pulled into a bun so tight it gives her headaches by hour six of every shift.

She has worked this casino floor for three years, carrying trays that weigh more than hope.

Smiling at men whose hands find her waist like it’s public property.

Existing in that peculiar space reserved for women who serve.

Visible enough to be useful.

Invisible enough to be ignored.

This is the art she has mastered.

Becoming a ghost while still breathing.

The uniform helps.

Black dress cut just low enough to encourage tips, but high enough to maintain the casino’s veneer of class.

Sheer stockings that run at the slightest provocation.

Heels that murder feet but make legs look longer.

A name tag that says Solidad in cursive script.

Though most guests call her sweetheart or honey or simply snap their fingers and point at empty glasses.

She doesn’t correct them.

Ghosts don’t have names.

Her shift starts at 6:00 p.

m.

and ends at 4:00 a.

m.

The graveyard they call it, though Solidad has always found that darkly appropriate.

These are the hours when the desperate come out.

When the men who told their wives they were at business dinners are $3,000 down and contemplating the credit cards they swore they’d never max out.

When the professional gamblers with dead eyes and systems that don’t work chase losses that compound like interest on the debt Solidad carries across the Pacific.

Every dollar she earns, every single one disappears into the machinery of survival.

Her mother, Elena, lives in Tand, Manila’s densest slum district in the same apartment where Solidad grew up.

The walls are so thin, neighbors can hear each other’s arguments and prayers in equal measure.

Elena has a heart condition that requires medication costing $600 American dollars per month.

In the Philippines, that’s 3 months wages for most people.

Without it, she dies.

The math is that simple, that brutal.

Solidad’s brother Miguel is 16 and brilliant.

Scholarship student at a technical college, top of his class, dreams of becoming an engineer.

His tuition is 400 monthly.

His future costs less than his mother’s heartbeat, but requires the same ruthless consistency.

Then there’s the debt.

$8,000 borrowed from a recruitment agency to get Solidad to America.

Visa fees, processing fees, travel costs, fees for fees, 20% interest.

She has been paying 500 monthly for 3 years and still owes 3,400.

The numbers are designed never to reach zero.

After rent, $750 for a bedroom she shares with another Filipino woman in an apartment that houses four of them total.

Solidad has maybe $200 to $300 for food, toiletries, bus fair, the phone card she uses to call home every Sunday.

She hasn’t bought new clothes in 2 years.

She cuts her own hair in the bathroom mirror.

She eats rice and canned goods and whatever mistakes the kitchen staff are allowed to take home.

This is the mathematics of being invisible.

A woman is worth exactly what she can send home, minus what it costs to keep her body functional enough to work tomorrow.

But here’s what they don’t understand about invisible people.

They see everything.

For 3 years, Solidad has watched women arrive at this casino like migratory birds following a route mapped by desperation.

Always Filipina, always young, early 20s mostly, with that particular light in their eyes that comes from believing the promises printed on recruitment brochures.

Good job.

American visa.

Five-star hotel.

Family saved.

Solidad recognizes that light because she wore it once.

Stepping off the plane at McCarron International Airport with a suitcase held together by duct tape and prayers, thinking she was the lucky one who got out.

The first girl she noticed was Maria.

Solidad never learned her last name.

June, 3 years ago, right after she started working at the Mirage Royale.

Maria was maybe 22.

pretty in that way that makes Western men think of tropical vacations and women who need saving.

Hired as a hospitality coordinator, a title so vague it meant everything and nothing.

She wore designer dresses that didn’t fit right, too big in the shoulders, too tight at the hips, like they’d been bought for a body that existed only in someone’s imagination of what she should be.

Solidad would see her sometimes in the service elevators, escorted by security to the penthouse floors where only VIP guests stayed.

Maria never made eye contact, never spoke, just stood there with her hands folded and her face arranged in an expression of careful blankness that Solidad understood intimately.

The expression of a woman who has learned that showing emotion is dangerous.

6 weeks after she arrived, Maria was gone.

Returned to the Philippines voluntarily, management said homesick, couldn’t adjust to American culture.

It happens.

Except Solidad talked to Rosa, one of the cleaning crew.

Rosa has worked at the Mirage Royale 8 years, cleaning the rooms where the casino’s secrets hide in the cracks between luxury.

She told Solidad that Maria’s passport never processed through customs.

No departure record, no flight manifest.

The girl simply vanished like she’d never existed at all, and the only people asking questions were other Filipinos who knew better than to ask too loudly.

3 months later came Angela, younger than Maria, quieter, with bruises hidden under makeup.

that was one shade too light for her skin.

Solidad was restocking vending machines in the service stairwell when she saw Angela being led, not walked, led to an appointment by a security guard whose hand on her lower back was possessive in a way that made Soladad’s stomach turn.

Solidad couldn’t help herself.

She broke the first rule of invisibility.

She made herself seen.

Are you okay? she asked.

In Tagalog, the language of home, the language that creates instant solidarity among Filipinos scattered across foreign countries.

Angela looked at her with eyes that had already learned not to hope.

“How do I leave without my passport?” she whispered.

Solidad had been carrying Detective Ray Martinez’s card for months.

Found it tucked in a bathroom stall with a message written in Tagalog.

“If you need help, call this number.

He can be trusted.

” She’d kept it not because she thought she’d ever need it, but because throwing away a potential lifeline felt like tempting God.

She gave Angela the card, told her to call from a pay phone, not from any phone the casino could monitor.

Angela took it with hands that shook.

That night, Angela disappeared.

Not deported, not relocated, simply erased.

Security footage deleted.

Manager claimed she’d never worked there.

Must be confused with someone else.

The card Solidad gave her was never found.

Solidad learned later, much later from Detective Martinez himself that Angela had called him.

Arranged a meeting at a diner off the strip.

Never showed up.

3 days afterward, police found her body in a motel room on the bad side of Fremont Street.

Official report, overdose, sex worker.

Tragic, but common.

Martinez told Solidad he knew it was murder.

knew someone had forced drugs into Angela’s system and staged the scene.

But his lieutenant shut down the investigation.

Waste of resources.

These girls chose this life.

Nothing to be done.

That’s when Solidad understood the pattern wasn’t just about women disappearing.

It was about women being disappeared with the full knowledge and silent permission of systems designed to protect people like her, but which only ever protected people like them.

Still, she said nothing.

Did nothing.

Every shift she served drinks and collected tips and wired money home and told herself she was powerless.

Told herself she was just one woman.

Told herself that staying silent kept her mother’s heartbeating and her brother in school and her own visa secure.

She told herself a lot of things.

The truth the truth she didn’t want to face was simpler and uglier.

She was afraid.

Afraid of losing everything she’d sacrificed 3 years to build.

Afraid of being deported back to poverty that would swallow her family whole.

Afraid of ending up like Angela, found in a motel room with a needle in her arm and no one believing she’d been murdered.

Fear is a cage built one rationalization at a time until the imprisoned can’t remember what it felt like to stand in open air.

But Solidad had a cousin named Terresa Santos.

She was 3 years older than Soladad, beautiful and ambitious and desperate to save her own family from the kind of poverty that grinds people into dust.

In 2007, Teresa accepted a job offer in Dubai.

Hotel work, housekeeping supervisor, good salary, everything Solidad had been promised when she came to Las Vegas.

For the first month, Teresa’s Instagram showed poolside photos and glamorous outings and captions about how she’d finally made it.

The second month, the photos became less frequent, her smile more strained, something dark creeping behind her eyes that the filters couldn’t quite hide.

The third month, her post stopped entirely.

Phone disconnected.

Email bounced back.

Her family’s inquiries hit bureaucratic walls built specifically to keep people like them from finding people like her.

In 2008, a Filipino migrant worker advocacy group confirmed what the family already knew.

Terresa Santos was missing, presumed trafficked, likely dead.

Her body was never found.

No one was ever arrested.

The world moved on like she’d never existed.

Solidad carries Teresa’s last photo in her wallet.

She looks at it every night before sleep, a ritual of remembrance and guilt.

She had told Teresa to take that job.

She had said, “Go ae, make money for the family.

This is your chance.

” Those words are knives that live in her chest.

So yes, Solidad saw the pattern, recognized the signs, knew something evil was happening in the floors above her head.

and she did nothing because doing something meant risking everything and she’d already decided that her family’s survival mattered more than her conscience.

That was the calculation she made every single shift for 3 years.

Then she saw her.

Tuesday night, 15 minutes before midnight, Solidad Cruz carries a tray of champagne flutes toward the private elevator bay on the 32nd floor.

Dom Peragnon, $400 a bottle, 12 glasses arranged in perfect geometric precision.

the kind of delivery that requires security clearance and absolute discretion because the people who drink this particular champagne don’t want to be seen by the people who can’t afford it.

The elevator bay is all marble and crystal chandeliers and mirrors polished so thoroughly a person can see their soul if they’re brave enough to look.

Solidad has learned to walk through this place without seeing her own reflection because the woman in those mirrors reminds her too much of what she’s become.

She rounds the corner, her heels clicking against marble that costs more per square foot than she earns in a month.

And she sees the girl before her brain processes who she is.

Young, maybe 19 or 20, Filipina, obvious from the shape of her face, the texture of her hair, the particular shade of brown skin that speaks of island sun and tropical humidity.

She’s wearing a crimson dress.

Versace.

Solidad recognizes the cut from magazines she looks at in grocery stores she can’t afford to shop in.

But it doesn’t fit right.

Too large in the shoulders, too tight at the hips, cutting into her ribs like it was bought for someone else’s idea of what her body should be.

Her feet are bare and bleeding in designer heels that clearly weren’t broken in before someone forced them on her.

Mascara smudged beneath her eyes in the telltale pattern of crying that’s been hastily concealed.

And her eyes, God, her eyes have that fractured quality Solidad has seen in every girl who passed through this place.

That look of someone whose hope has been surgically removed without anesthesia.

She’s standing next to a security guard whose hand rests on her lower back in a way that has nothing to do with guidance and everything to do with ownership.

They’re waiting for the elevator that goes to the penthouse suites, the floors that don’t officially exist on the casino directory, the places where men with enough money can buy anything.

The girl turns her head.

Their eyes meet.

Solidad’s brain catches up to what her body already knows.

The tray falls.

12 crystal champagne flutes explode against marble like tiny bombs.

For $100 of Dom Peragnon bleeds across white stone in expanding puddles that catch the chandelier light and throw it back as fractured rainbows.

The sound echoes through the elevator bay, impossibly loud in the cultivated silence of the VIP floors.

But Soladad doesn’t hear it.

She doesn’t hear anything except the blood rushing in her ears and her heart trying to break through her ribs and her mother’s voice from 15 years ago saying, “Take care of your brother’s children.

” Anic, promise me, family protects family.

The girl in the crimson dress is Sophia Cruz, Solidad’s niece, her brother Miguel’s oldest daughter.

19 years old with her father’s dimples and her mother’s gentle hands and three years of college still ahead of her and a whole life that was supposed to be different from this, better than this, saved from this.

Time fractures.

Solidad is on her hands and knees in champagne and broken glass, but she doesn’t feel the shards cutting her palms.

She’s staring at Sophia, but the girl is looking away, her training already kicking in.

Don’t acknowledge.

Don’t react.

Don’t give them any reason to notice anything.

The security guard’s hand twitches toward his sidearm, his body language shifting from board escort to potential threat assessment.

The floor manager materializes from somewhere, his face arranged in that particular expression of service industry fury that never shows in front of guests but flays employees alive in private.

Clean this up.

He hisses now.

Cost docked from your paycheck.

Move.

Sophia is already in the elevator.

The doors close.

She’s gone.

Solidad picks glass out of champagne puddles with hands that shake so violently she cuts herself three more times.

Blood mixes with alcohol, pink and thin like watered down hope.

Someone brings a mop.

Someone else brings a tray to collect the broken crystal.

She does what she’s told because that’s what invisible people do.

They clean up messes and pretend their worlds haven’t just shattered alongside the glassware.

3 weeks ago, Sophia sent her aunt a message on WhatsApp.

The words are burned into Soladad’s memory with the permanence of scars.

Teta Soul, guess what? I got a job.

Five-star hotel in Las Vegas.

Housekeeping supervisor position.

They’re paying for my flight, visa, everything.

$3,000 a month salary.

I can pay for Papa’s surgery.

His kidneys are failing.

This job saves his life.

Isn’t it amazing? And it’s at the Mirage Royale where you work.

Maybe I’ll see you.

Solidad had felt something cold wrap around her spine when she read that message.

Some instinct screaming danger in a language she’d been taught to ignore.

But the logical part of her brain, the part that pays bills and makes calculations, argued back.

3,000 monthly was real money.

The Mirage Royale was a legitimate casino.

Lots of Filipinos worked in Las Vegas hospitality.

This could be exactly what it claimed to be.

She typed back, “That’s wonderful, Anic.

Be careful.

Read the contract carefully.

Keep your passport safe.

Call me when you land.

Sophia landed three weeks ago.

Never called.

Solidad told herself the girl was busy adjusting, overwhelmed by new job responsibilities.

She told herself a lot of things because the alternative, the truth she’d been watching for 3 years, was too terrible to face when it was happening to her own blood.

Now she knows.

Now she’s seen.

Now there’s no more pretending.

At 4:17 in the morning, Solidad clocks out, but she doesn’t go home.

She changes into a cleaning crew uniform borrowed from the storage closet, the universal costume of invisibility that grants access to spaces where waitresses aren’t allowed.

She takes a master key card she found 6 months ago and never reported.

Keeping it tucked in her locker for reasons she couldn’t articulate then, but understands now.

She joins the Filipina cleaning crew on the overnight shift.

Maria, Rosa, LSE, women she’s known for three years.

Women who’ve shared meals and complaints and the particular solidarity that comes from being foreign and female and poor in a place designed to extract everything they have.

Soul, what are you doing here? Maria asks, her eyes narrowing with the kind of concern that comes from knowing when someone’s about to do something dangerous.

Your shift ended an hour ago.

Needed the overtime.

Solidad lies.

Mother’s medical bills.

They understand immediately.

Overtime is code for desperation, and desperation is a language they all speak fluently.

But Maria isn’t fooled.

She steps closer, lowers her voice to a whisper that barely carries over the industrial vacuum cleaner, humming in the hallway.

You’re looking for the new girl, your niece.

Solidad’s shock must show on her face because Rosa touches her arm gently, her expression heavy with the weight of things she wishes she didn’t know.

We all have eyes, soul.

We all have families.

We know what happens up there.

Tell me, Solidad says, and her voice sounds like someone else’s.

Harder, sharper, belonging to a woman who stopped being afraid of consequences because the worst thing has already happened.

They tell her everything.

The girls are kept in suites 3401 through 3406, the penthouse residential section that’s listed as executive housing on the official floor plans, but which functions as a prison with room service.

They’re rotated through VIP guest rooms for appointments.

That’s what the men call them, appointments, like the girls are dentists instead of human beings being rented by the hour.

Food is delivered by security, never by room service staff who might ask questions or remember faces.

Laundry is collected in sealed black bags, and Rosa has seen the blood stains, the torn fabric, the evidence of what happens in those rooms that everyone pretends not to know.

The girls contracts are held by something called Executive Hospitality Services LLC, which sounds legitimate until one realizes it’s owned by Victor Rothstein, the casino owner himself.

A man who built his fortune on knowing exactly how to exploit the space between legal and ethical, who understands that the law protects property, and people like him are the ones who get to decide which category others fall into.

There’s a basement level, LSE adds.

crossing herself like the gesture might protect her from the knowledge she’s about to share.

Blueprint says mechanical systems, but cleaning crews are never allowed down there.

Security only.

Girls who cause problems go to the basement.

Some don’t come back up.

Solidad’s hands are shaking again.

She clenches them into fists, feels her nails dig into palms already cut by champagne glass, uses the pain to focus.

I need to get into Rothstein’s office tonight.

Can you help me? They exchange glances, the kind of wordless communication that comes from years of working together in hostile territory.

Finally, Maria nods.

15 minutes.

That’s all we can give you.

I’ll stand watch.

But Soul, if you get caught, we can’t help you.

We have families, too.

I know.

Solidad tells her.

I wouldn’t ask if there was any other choice.

Victor Rothstein’s office is on the 34th floor, northwest corner, all glass walls and modernist furniture.

and the kind of aggressive luxury that announces its owner made it by stepping on everyone else.

The door is locked, but the master key card opens it with a soft click that sounds deafening in the silent hallway.

Solidad has 15 minutes to find something, anything that can save her niece.

The office is immaculate in that way that suggests either obsessive organization or someone who pays people to be obsessive for them.

Desk made of some dark wood that probably cost more than Solidad’s annual salary.

leather chair that probably costs more than her mother’s heart medication.

Abstract art on the walls that she doesn’t understand, but which she’s sure is expensive because everything in this room screams money with the volume of people who never had to worry about it.

But Rothstein made a mistake that rich men often make.

He’s arrogant.

Arrogant enough to believe that people like Solidad Cruz are too invisible, too powerless, too cowed by his authority to ever pose a threat.

So he leaves things out careless on his desk left open like it’s not evidence of slavery in the 21st century is a ledger handwritten which seems almost quaint in the age of digital everything but the logic is clear.

Handwritten records don’t leave the kind of electronic trail that law enforcement can follow.

The pages are filled with entries that make Solidad’s blood turn to ice water in her veins.

Manila package 18.

Manila package 19.

Manila package 23.

not names, package numbers, like their shipping containers instead of human beings.

Next to each package number, arrival dates, procurement costs, revenue tracking.

Solidad finds Sophia’s entry halfway down the page.

MP23 arrived 3 weeks ago.

Revenue to date, $87,400.

Her 19-year-old niece has generated nearly $90,000 in 3 weeks.

Solidad does the math, the terrible, sickening math, and realizes that means somewhere between 40 and 80 appointments, depending on what the men paid for her.

She’s going to vomit.

She forces it down.

No time.

12 minutes left.

She photographs every page with her phone, her hands shaking so badly, some of the pictures are blurred.

She’ll take them again tomorrow if she has to.

Right now, she needs everything she can get.

The trash basket yields flight manifests.

Private charter flights from Manila to Las Vegas.

Monthly schedule.

Passenger lists of four to eight young women per flight.

Departure.

Ninoi Aino International Airport.

Arrival.

Desert Springs Private Airfield 40 miles outside Las Vegas.

Small enough to avoid the scrutiny that comes with major airports.

A locked drawer.

Rosa taught Solidad how to pick basic locks last year.

She said, “Every cleaning woman should know how because rich people are always locking themselves out of things and expecting them to fix their mistakes.

” Solidad uses a bobby pin from her hair, fumbles for 30 seconds that feel like 30 years, and the drawer clicks open.

Passports, 22 of them, rubber banded together like a deck of cards.

She flips through them, all Filipina, all women, all ages 19 to 26.

She finds Sophia’s.

Her photo shows her eyes still bright with hope with belief that the world was offering her a chance instead of a trap.

Solidad photographs every passport, documents every face, bears witness to every stolen identity.

10 minutes filing cabinet not locked.

More arrogance folders labeled by year.

She pulls 2012 inside contracts.

The executive hospitality services employment agreement.

Legal language that sounds legitimate until one finds the clause buried on page seven.

Employee agrees to specialized service requirements as determined by management discretion.

Specialized service requirements.

That’s what they call it.

That’s how they make slavery sound like a job description.

The penalty for breaking contract.

$50,000 plus legal fees.

Impossible sums designed to be impossible.

Designed to trap.

Designed to make girls believe they can never leave because debt doesn’t end.

only compounds.

Solidad photographs everything.

247 photos in 15 minutes.

Her phone storage is nearly full.

She uploads everything immediately to three separate cloud accounts she created months ago under false names.

Encrypts everything.

Backs up everything.

Deletes the originals from her phone in case they confiscate it.

Maria appears in the doorway, her face tight with fear.

Time.

Security changes shift in 3 minutes.

They leave exactly how they came.

Invisible women pushing cleaning carts through hallways designed to let rich people forget they exist.

No one stops them.

No one even looks at them.

At 4:47 a.

m.

, Solidad is in a service stairwell trying to catch her breath when she hears footsteps.

She freezes.

The door above her opens.

She crouches behind the landing, makes herself small, makes herself nothing.

Sophia appears, escorted by the same security guard from earlier.

They’re descending from the penthouse level.

Solidad can hear him speaking, his voice low and conversational like he’s escorting someone to coffee instead of to another appointment where her body will be sold to someone who doesn’t care if she bleeds.

Solidad can’t help herself.

She breaks every rule of safety and survival.

She steps out from behind the landing.

Sophia, she whispers into Galog.

Anic, it’s me.

Sophia looks at her and for one moment, one brief shattering moment, Solidad sees recognition.

She sees her niece, the girl who used to call her every Sunday to tell her about college classes and dreams of becoming a teacher.

Then Sophia’s face goes blank.

That careful practice blankness Solidad has seen on every traffic girl.

The expression that keeps them alive by pretending they’re already dead inside.

I don’t know you, Sophia says in English, her voice flat and ackless.

Your father needs you.

Solidad tries, desperation making her reckless.

Your mother prays for you every night.

I can help you leave.

The security guard steps between them, his hand resting on the weapon at his hip.

No staff fraternization.

Move along.

Sophia looks at Soladad one more time.

And this time, tears gather at the corners of her eyes, threatening to ruin her mascara.

She whispers so quietly.

Solidad almost misses it.

Don’t try to save me, Ta.

They’ll kill you.

They’ve killed others.

Then she’s gone, descending the stairs to whatever fresh horror awaits her, and Soladad is left standing there with evidence in her cloud storage and rage in her chest and the certain knowledge that staying invisible is no longer an option.

At 5:47 in the morning, Soladad walks to her apartment as the sun rises over Las Vegas, painting the desert sky in shades of red and gold that remind her of blood and fire.

She’s been awake for 23 hours.

Her hands are cut from champagne glass and shaking from adrenaline crash.

Her phone holds evidence that could destroy a multi-million dollar trafficking operation.

And she’s about to make a phone call that will either save her niece or get them both killed.

She dials the number on the card she gave Angela 8 months ago.

The card Angela died carrying.

The number belonging to the one cop who might give a damn about girls like them.

It rings four times.

Solidad is about to hang up when a voice answers.

Rough with sleep but alert.

Detective Martinez, Las Vegas Metro.

How can I help you? Solidad takes a breath, closes her eyes.

Thinks of Teresa and Angela and Sophia and all the girls whose names she doesn’t know, but whose faces she’s memorized.

Thinks of her mother praying her rosary in Manila.

Thinks of the woman she was 3 years ago stepping off a plane with hope in her suitcase.

Thinks of the woman she needs to become.

My name is Soladad Cruz, she says, and her voice doesn’t shake.

I have evidence of human trafficking at the Mirage Royale Casino.

Tell me how much you need to bring them down.

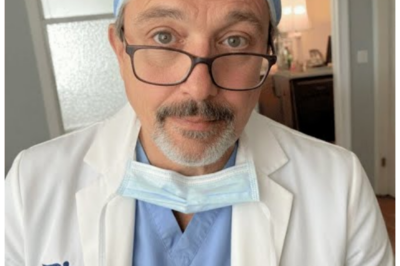

Detective Ray Martinez looks exactly like someone who has spent 18 years watching the system fail the people it’s supposed to protect.

41 years old, second generation Mexican American with the kind of face that’s seen too much and the kind of eyes that refuse to stop looking anyway.

He meets Soladad Cruz at a diner on Boulder Highway at 6:30 in the morning, far enough from the strip that casino security won’t notice.

Anonymous enough that there just two more people having breakfast in a city that never sleeps.

Martinez orders coffee.

Black, no sugar.

Solidad orders nothing because her stomach is a clenched fist and the thought of food makes her want to vomit.

Tell me everything, he says.

And there’s something in his voice that makes her believe him.

Don’t clean it up.

Don’t make it easier for me to hear.

Give me the truth.

So she does.

She tells him about three years of patterns about Maria and Angela and the dozen other girls whose faces she memorized and whose names she never learned.

She tells him about Teresa, her cousin who disappeared in Dubai, whose Instagram went dark and whose family’s inquiries hit bureaucratic walls built specifically to keep people like them from finding people like her.

She tells him about Sophia, about seeing her niece in a crimson dress that didn’t fit right, about the $87,000 the girl has generated in 3 weeks, about the way her eyes have already learned not to hope.

Solidad shows Martinez her phone.

247 photographs of ledgers and flight manifests and passports and contracts, evidence of an operation so sophisticated it’s been running for years right under the nose of law enforcement, or more likely with their quiet permission.

Martinez goes very still as he scrolls through the images.

His jaw tightens.

His knuckles go white around his coffee cup.

When he finally looks up at Solidad, there’s something in his expression that she recognizes because she’s been wearing it herself for the past 6 hours.

Rage so absolute it transcends emotion and becomes purpose.

I know about Angela, he says quietly.

The girl who overdosed 8 months ago, she called me.

We set up a meeting.

She never showed.

I found her 3 days later in that motel room with a needle in her arm that someone else put there.

I knew it was murder.

I tried to investigate.

My lieutenant shut me down.

Said I was wasting resources on a prostitute who chose that life.

His voice is completely flat.

But Soladad can hear the fury underneath.

The kind that comes from watching evil win because good men are ordered to look away.

Your lieutenant, she says carefully.

He shut you down.

Marcus Webb, 20-year veteran.

Good cop, I thought.

Martinez’s smile is bitter.

Turns out good cops don’t drive Cadillacs on a lieutenant’s salary.

Don’t send their kids to private schools that cost 40,000 a year.

I started looking into his finances 6 months ago.

Off the books, he’s dirty.

And if he’s dirty, I have to assume there are others.

This is what Solidad suspected but didn’t want to believe.

That the corruption isn’t just Rothstein buying off individual cops, but systemic protection that goes high enough to make investigation impossible through normal channels.

So, what do we do? She asks.

We build a case so airtight that even corrupt cops can’t kill it.

Then we go to the FBI.

He pulls out a notebook, starts writing.

I need you to keep working at the casino.

I know that sounds insane given what you’ve just told me, but we need more.

We need financial records linking Rothstein to the LLC.

We need testimony from the girls, multiple girls, not just Sophia.

We need to document the client base, especially if there are politicians or judges involved.

And most importantly, he pauses, meets her eyes with an expression that tells her he knows what he’s about to ask is potentially fatal.

We need a wire recording of Rothstein admitting to trafficking.

Everything else is circumstantial.

strong circumstantial, but his lawyers will tear it apart.

I need his voice on tape saying, “I traffic women.

” Without that, he walks.

Solidad understands what he’s telling her.

Someone has to get close enough to Victor Rothstein to make him confess on tape.

Someone has to wear a wire into the lion’s den and survive long enough to get him talking.

That someone is her.

How long? She asks.

For months, minimum, maybe six.

We need to be thorough.

one shot at this.

If we move too early and he gets acquitted, he disappears and takes the whole operation underground where we’ll never find it again.

Four to six months.

Four to six months of watching her niece be destroyed piece by piece while Solidad gathers evidence.

For to 6 months of serving drinks to men who are raping girls Sophia’s age.

Four to 6 months of smiling and staying invisible while everything inside her screams.

I’ll do it, she says, because there’s no other answer.

Tell me what you need.

Over the next four months, Solidad Cruz becomes two people.

During the day, she’s the cocktail waitress, invisible and compliant, and exactly what Victor Rothstein’s system expects her to be.

At night, she’s someone else, a hunter, learning the architecture of her praise empire, documenting every detail with the patience of someone who understands that justice delayed is better than justice denied.

The cleaning crew becomes her intelligence network.

Maria, Rosa, LSE, and six other Filipino women who have spent years watching atrocities they couldn’t stop.

They teach Soladad things.

Rosa shows her how to pick locks with bobby pins and dental tools.

LSE explains the security camera blind spots, the 60-second gaps when guards change positions.

Maria gives her the radio frequency security uses, teaches her their codes, helps her understand when it’s safe to move and when she needs to become a ghost.

In return, Solidad gives them hope.

Not the cheap kind that costs nothing, but the expensive kind that requires sacrifice.

She tells them about Detective Martinez, about the FBI investigation being built brick by brick, about the possibility that this time maybe the girls might actually be saved.

Solidad befriends the victims carefully, building trust over weeks and months.

Carmen, who thought she was coming to be a housekeeper and learned on her first night what she really was.

Jasmine, whose real name is Maria, but who was given an American name because clients prefer the fantasy.

Isabelle, who whispers to Solidad in Tagalog about the basement level where girls who resist are taken for discipline, administered by Dmitri Vulov, Rothstein’s head of security, a former Bellarusian military man with dead eyes and scarred knuckles.

Solidad learns that Dmitri is the enforcer, the one who handles the violence that keeps the operation running.

The girls call him the Siberian in whispers, like saying his name too loud will summon him.

He’s the reason they comply even when every instinct screams to run.

Because the girls who ran ended up in the basement, and some of them never came back up.

One night, in her third month of investigation, Solidad bribes a kitchen worker $200, half a month’s food budget to let her use the freight elevator that accesses the basement level.

What she finds there will haunt her for the rest of her life.

The basement is a concrete bunker beneath the casino’s foundation, not on any official blueprint, accessed only by security with special clearance.

There’s a medical examination room with stirrups and gynecological equipment, where new arrivals are processed, tested for diseases, given birth control shots, cataloged like inventory.

There’s a soundproof discipline room with restraints on the walls and stains on the concrete floor that Solidad recognizes as blood, even in the dim light.

There’s a storage area containing sedatives and painkillers, enough to keep dozens of girls compliant.

And there’s an office containing filing cabinets that should have been locked but aren’t.

More of Rothstein’s arrogance showing through his operational security.

Solidad finds a folder labeled retired assets.

And inside are profiles of 34 girls from 2008 to 2012.

Next to their names, their real names, not the codes from the ledger, are classifications.

11 marked deported, eight marked relocated, six marked medical, and nine marked disposed with GPS coordinates that point to locations deep in the Mojave Desert.

Solidad photographs everything with hands that shake so badly she has to take multiple shots to get clear images.

She barely makes it out before the security shift change, and when she finally reaches the parking garage, she vomits for 20 minutes.

Her body trying to purge the knowledge of what she’s seen.

Detective Martinez confirms her worst fears when she shows him the coordinates.

Three of them match locations where human remains have been found over the past 5 years.

Jane does unidentified cases that went cold because no one cared enough to push for answers when the victims were likely sex workers or undocumented immigrants.

This is a murder investigation now, Martinez says.

And Solidad can see the weight of it settling on him.

Multiple homicides, Rico charges.

This goes to the FBI tomorrow.

He contacts special agent Linda Reyes.

FBI human trafficking unit out of the Los Angeles field office, not Las Vegas, because Las Vegas FBI has a suspicious record of failed trafficking prosecutions that suggests either incompetence or corruption.

Reyes is Filipino American, which means she understands in her bones what’s happening to these girls.

She reviews their evidence and gives them the answer Solidad already knew was coming.

This is prosecutable.

She says we can freeze his assets.

Revoke the girl’s deportation risk.

Charge him under RICO statutes.

But I need one thing you don’t have yet.

Wire recording of Rothstein explicitly admitting to trafficking.

Everything else is strong circumstantial.

I need his voice.

Which brings them back to the same question.

Who wears the wire? The answer hasn’t changed.

But Victor Rothstein is starting to notice Solidad.

And that’s when everything becomes exponentially more dangerous.

In her fourth month of investigation, he personally requests her for a private party in his penthouse suite.

Eight VIP guests, judges, businessmen, a Nevada state senator, and six girls circulating like appetizers, including Sophia, who doesn’t recognize her aunt anymore.

The girl’s eyes have gone completely flat.

The light behind them extinguished so thoroughly, Solidad wonders if it can ever be rekindled.

Rothstein watches Solidad all evening.

Tests her with questions that seem casual but aren’t.

You’ve been with us 3 years, Solidad.

Loyal, hardworking.

I appreciate that.

His voice is smooth, cultured, the accent of his Romanian immigrant origins almost completely erased.

Your mother, Elena, yes, she’s doing better.

The heart medication working.

He knows her mother’s name.

He’s researched her.

The threat is implicit but unmistakable.

Yes, sir.

Solidad says, keeping her eyes down, playing the role of the compliant servant.

Thank you for asking.

And your brother, Miguel, bright boy, scholarship student.

You must be proud.

He pauses, lets the words hang in the air like a noose.

Family is everything, isn’t it? We do anything to protect them.

Even difficult things, even looking the other way sometimes.

His hand rests on her shoulder, heavy with implied violence.

I value loyalty, Solidad.

Disloyalty, though that’s dangerous for everyone involved.

You understand? Yes, Mr.

Rothstein.

I understand.

He dismisses her.

But the message is delivered.

He suspects something.

Maybe not the full scope, but enough to be watching her now.

Enough to be making sure she knows that he can reach her family 8,000 m away if she becomes a problem.

That night, Solidad calls Martinez, and her voice doesn’t shake when she tells him.

He knows something’s wrong.

We need to move.

We’re not ready.

We need the wire recording first.

He threatened my family.

If we wait, he’ll either kill me or disappear the entire operation.

If we move without that recording, he walks.

His lawyers bury the case.

He retaliates against every witness.

You, Sophia, all the other girls.

Everyone dies or disappears.

The math is brutal and simple.

Without Rothstein’s confession on tape, the case collapses.

with it.

They might actually save them.

But getting it means walking into a trap Soladad knows is waiting.

“I’ll wear the wire,” she says.

“Soladad, I’ll wear the wire,” she repeats.

And this time, her voice does shake, not with fear, but with the kind of certainty that comes when someone has finally stopped running from the only choice they ever really had.

“Set it up.

Tell me when.

” Martinez is silent for a long moment, then two weeks.

I’ll coordinate with the FBI.

We’ll wire you.

You get him talking, we raid within 48 hours.

That’s the window.

2 days between recording and arrests before he can retaliate.

If he finds the wire, Solidad asks, though she already knows the answer.

Then you’re dead.

I’m sorry.

I wish I had another answer.

Solidad thinks about her mother praying her rosary in Manila.

About her brother Miguel and his dreams of becoming an engineer.

About Teresa disappeared in Dubai.

About Angela found with a needle in her arm.

About Sophia’s extinguished eyes.

About the nine girls marked disposed with desert coordinates next to their names.

My mother used to say, “God doesn’t give you strength to avoid the cross.

He gives you strength to carry it.

” She closes her eyes.

I’ll wear the wire.

The FBI safe house is a suburban rancher in a neighborhood where all the houses look identical.

The kind of anonymous American architecture designed to be forgettable.

Special Agent Linda Reyes walks Solidad through the wire device.

Smaller than a lipstick tube sewn into the underwire of her bra, where even an aggressive search is unlikely to find it.

12-hour battery life.

Records locally rather than transmitting, which makes it harder to detect, but also means if something goes wrong, the device has to be physically recovered from her body.

Living or dead, “Your job is simple but terrifying.

” Reyes says her voice matter of fact in the way of people who deal with terrible things professionally.

Get him talking about the operation specifically.

We need him to say that he traffs women that he uses force or coercion that he profits from their sexual exploitation.

Names of co-conspirators if possible.

She teaches solidad interrogation techniques.

Play ignorant but curious.

Let him explain his system because criminals love explaining their cleverness.

Appeal to his ego.

Narcissists can’t resist bragging.

Play desperate.

Make him think she’s vulnerable, not a threat, maybe even recruitable.

What you don’t do, Reyes emphasizes, is ask direct questions like, “Are you trafficking women?” Don’t show fear.

He’ll sense it.

Don’t mention police or investigations.

Don’t try to save anyone during the recording.

Your job is evidence only.

Get in.

Get him talking.

Get out alive.

The night before, Solidad writes letters to her mother in Tagalog apologizing for failing to bring her to America like she promised, asking her to take care of Miguel, telling her she died fighting men who hurt women like them.

To Sophia, promising that even if she doesn’t survive, Sophia will.

The FBI will protect her.

She’ll heal eventually, and when she does, she needs to live loudly for both of them.

To Martinez, making him promise that if the wire fails and she dies, he’ll still raid.

He’ll still get the girls out even without the evidence.

Solidad seals them in envelopes and leaves them in her apartment with instructions.

Open if I don’t return by Monday.

At 5:00 in the morning, she attends mass at St.

Joseph’s Catholic Church where the Filipina immigrant community gathers.

She confesses to the priest that she’s about to do something dangerous and asks if it’s worth it to die trying to save others.

He tells her God doesn’t call his people to be safe.

He calls them to be faithful and what she’s doing is faithful.

She takes communion, lights a candle for Teresa, and prays the rosary until her fingers know the words better than her brain does.

The FBI wires her at noon.

The process takes 30 minutes and hurts more than she expected.

The device sewn carefully into the bra’s underwire with surgical precision.

They test the recording.

Her voice comes back clear, every word crisp and damning.

Solidad practices staying calm, practices facial expressions, practices being someone who isn’t terrified.

At 6:45 p.

m.

, a black SUV arrives at her apartment.

The driver is silent and armed.

As they leave the city and drive into the desert, Solidad watches civilization disappear in the rearview mirror and understands that this is where girls like Angela ended up.

The desert doesn’t judge, it just swallows.

Rothstein’s estate rises from the Mojave like a monument to greed.

12,000 square feet of glass and steel.

Helicopter pad on the roof.

8-ft security walls surrounding the property.

The nearest neighbor is 15 mi away.

Cell service is non-existent.

Deliberately jammed.

If something goes wrong here, Solidad is 40 minutes from help.

If something goes wrong here, she’s dead.

The dinner party is already underway when she arrives.

11 guests in the glasswalled dining room overlooking the desert sunset that bleeds red and orange like a wound across the sky.

Solidad recognizes most of them.

Senator Howard Blackwell, who she’s watched enter sweet 3404 with 21-year-old girls.

Judge Patricia Mendoza, who’s dismissed three trafficking cases against Rothstein’s associates.

Lieutenant Marcus Webb, Martinez’s boss, the betrayer who’s been feeding information to Rothstein for years.

Three businessmen who are partners in the trafficking network.

Dimmitri Vulov lurking in the background like a shadow with a pulse.

Rothstein’s wife Celeste, distant and medicated, looking at everything and seeing nothing.

Solidad’s job is to serve drinks and stay invisible.

Listen.

Wait for the opening.

It comes after dinner when the guests move to the private lounge and Senator Blackwell drunk on bourbon and impunity laughs and asks, “Victor, once they arrive, I keep their passports.

” Standard practice.

They owe me recruitment fees.

Travel costs 20 $30,000.

Impossible to repay on legitimate wages.

The wire is recording.

Deceptive recruitment.

Debt bondage.

Solidad thinks, “Keep talking.

Keep talking.

” One of the businessmen asks, “But what if they run? Call police.

” Rothstein’s laugh is genuine amusement.

Who do they call? Lieutenant Web ensures my operations aren’t interrupted.

Judge Mendoza handles any legal complications and if someone becomes truly problematic, he glances at Dmitri.

Dimmitri’s voice is flat, emotionless, Eastern European accent thick.

I handle problems permanently.

Conspiracy to murder.

Witness tampering.

It’s all on tape.

But Rothstein isn’t done.

He’s enjoying this too much.

This opportunity to show his dinner guests exactly how clever he is.

how completely he’s beaten the system designed to stop men like him.

Then he turns to Soladad.

Solidad, you’ve been very quiet tonight.

What do you think of my operation? The room goes silent.

Every eye turns to her.

The trap springs shut.

Her heart is a drum beaten by fists, but she keeps her face neutral.

Keeps her voice steady.

It’s very impressive, Mr.

Rothstein.

Very organized.

You’ve worked for me 3 years.

You’ve seen the girls come and go.

Ever wonder where they come from, where they go? He knows.

He’s playing with her, testing, threatening.

I assumed they were hospitality workers like me, she says, playing the role of the ignorant servant.

Rothstein stands, approaches her, and she can smell his cologne.

Expensive cloying, the scent of money earned from human suffering.

No, Soladad, their products, inventory, assets that generate revenue until they depreciate.

Then we retire them.

There it is.

Explicit admission of human trafficking.

Viewing victims as property.

All on tape.

But he’s not finished.

He circles her like a shark that’s detected blood.

You’re a smart woman, loyal, hardwork, but lately I’ve noticed you asking questions, spending time in places you shouldn’t be.

Detective Martinez, you know him? The room’s temperature drops 20°.

Lieutenant Web speaks up.

Martinez has been investigating you.

He’s been meeting with someone.

A Filipino woman about 5’3, late 20s casino employee.

Everyone understands.

They all know why she’s really here.

Rothstein’s voice shifts from casual to cold.

Solidad, I’m disappointed.

I gave you opportunities.

I trusted you and you’ve been working with police.

Search her.

Dmitri blocks the exit.

This is it.

If they find the wire, she’s dead.

The backup team is 10 minutes away.

Can she survive 10 minutes with Dimmitri? Solidad makes a choice.

Loud.

Clear.

The code phrase that triggers the raid.

I need to check on my mother.

Dimmitri’s fist crashes into her stomach.

She collapses, gasping, the world going white with pain.

She hears Rothstein sigh, almost regretful.

Such a waste.

You could have kept serving drinks.

Take her to the desert.

Make it look like an accident.

and make sure she talks first.

I want to know what she told Martinez.

The wire captures everything.

Rothstein ordering her murder.

Guests laughing, continuing to drink.

The senator making jokes about being more careful with hiring.

Rothstein’s voice.

By tomorrow, this problem disappears just like the others.

Dimmitri drags Solidad to a black SUV, throws her in the back.

Her hands are zip tied, blood in her mouth, but the wire is still recording.

7 hours of audio.

Even if she dies, the evidence survives.

That has to be enough.

They drive 20 m into the Mojave.

Middle of nowhere.

Dimmitri pulls her out and she sees headlights in the distance.

Multiple vehicles coming fast.

The FBI.

Martinez.

They’re coming, but Dimmitri sees them, too.

He pulls his pistol, presses it to her forehead.

Solidad closes her eyes, thinks of everyone she’s dying for.

Then sirens, spotlights, megaphones.

FBI, drop your weapons.

Dimmitri grabs Solidad, holds the gun to her head, tries to negotiate.

She remembers Martinez’s training.

If someone holds a gun to your head, you have nothing left to lose.

Fight.

She drives her elbow into his ribs, twists, drops.

His gun discharges, missing her head by inches.

The FBI sharpshooter doesn’t miss.

Dimmitri falls dead before he hits sand.

Martinez reaches her first, cradling her head.

The wire.

Did it record? Every word, she whispers before passing out.

At the estate, the FBI is arresting everyone.

Rothstein cuffed face first on his marble floor.

Senator Blackwell trying to claim immunity he doesn’t have.

Judge Mendoza demanding her lawyer.

Lieutenant Webb pulling his badge uselessly.

In the penthouse suites, 17 girls are freed.

Sophia is found in sweet 3404 curled in a corner, not believing rescue is real until an FBI agent shows her Soladad’s photo and says, “Your aunt sent us.

She saved you.

” At the hospital, Sophia rushes into Solidad’s ICU room.

Solidad is broken ribs and internal bleeding and concussion, but alive.

“Ta,” Sophia whispers, “You came for me.

” They hold each other and cry.

Both of them ghosts who refuse to stay invisible.

The trial begins 6 months after that night in the desert in a federal courthouse in downtown Las Vegas where the air conditioning runs too cold and the fluorescent lights make everyone look like corpses.

Solidad Cruz sits in the witness gallery wearing a borrowed suit from the FBI victim services coordinator because she doesn’t own anything appropriate for testifying in a federal racketeering case.

Her hands are folded in her lap to hide the tremor that never stopped after Dimmitri’s fist connected with her stomach.

after his gun pressed against her forehead after she understood with absolute clarity what it feels like to be seconds from death.

Victor Rothstein sits at the defense table in a $1,000 suit.

His silver hair perfectly styled, his expression one of mild annoyance rather than fear.

He has three attorneys, the kind that bill $800 per hour and specialize in making the impossible disappear.

They’ve already filed 17 motions to suppress evidence, to dismiss charges, to delay trial, all denied.

But their presence sends a message.

We have unlimited resources, and we will fight every millimeter of this prosecution.

The defendant’s box looks like a roster of Las Vegas power.

Senator Howard Blackwell, his political career in ruins, but his legal team still formidable.

Judge Patricia Mendoza, disbarred and facing 15 counts of corruption.

her face, a mask of contempt for the system that’s turning on her.

Lieutenant Marcus Webb, who spent 20 years pretending to serve and protect while actually serving and protecting traffickers.

Three businessmen whose names Solidad doesn’t remember, but whose faces she recognizes from that dinner party where they laughed while discussing human beings as inventory.

Dimmitri Vulov’s chair is empty.

Dead in the desert, killed during attempted escape.

The official report says no one mentions that he was shot trying to execute a federal witness.

No one asks too many questions about the ballistics.

The prosecution team is led by assistant US attorney Jennifer Morrison, a woman in her 40s with the kind of controlled fury that comes from spending a career watching powerful men by their way out of consequences.

She’s joined by special agent Linda Reyes and two other FBI agents who’ve spent six months building a case so comprehensive it fills 14 bankers boxes with evidence.

Day one is jury selection.

12 citizens of Las Vegas, a city built on moral compromise asked to judge a man who represents the logical endpoint of their entire economy.

Taking things from desperate people and selling them to rich people who don’t care where they came from.

Day two is opening statements.

Morrison stands before the jury and speaks for 47 minutes, laying out a narrative of systematic trafficking that operated for over a decade that destroyed hundreds of lives that generated tens of millions of dollars in profit from human suffering.

She shows them photographs of the 22 passports Solidad found in Rothstein’s desk.

She displays the ledger entries marking girls as Manila packages with revenue tracking next to their numbers.

She plays three minutes of the wire recording, just three minutes of Rothstein’s voice explaining how he controls girls through psychological manipulation and debt bondage.

The defense attorney stands up and speaks for 12 minutes.

His entire strategy boils down to the girls came voluntarily.

They were paid for services rendered.

Prostitution is a victimless crime and none of this rises to the level of trafficking.

It’s a lie so transparent observers can see through it, but it only needs to convince one juror.

Day four is Solidad’s testimony.

Morrison walks her through her entire story with the patience of someone who knows that credibility is built through detail.

Where she was born, Tanda, Manila, why she came to America to escape poverty to save her family.

How long she worked at the Mirage Royale 3 years.

What she witnessed.

Girls arriving with hope and leaving with something essential carved out of them or not leaving at all.

When did you first suspect human trafficking was occurring? Morrison asks, “The first girl I noticed was 3 years ago, Maria.

She arrived as a hospitality coordinator.

6 weeks later, management said she returned to the Philippines, but the cleaning crew confirmed her passport never processed through customs.

She just disappeared.

What did you do with this information?” “Nothing.

” Solidad’s voice catches.

This is the part she’s most ashamed of.

I did nothing for 3 years.

I told myself I was powerless.

I told myself my family’s survival depended on my silence.

I told myself a lot of things.

What changed? I saw my niece Sophia Cruz, 19 years old, in a red dress in the private elevator bay being escorted to the penthouse suites where the trafficked girls were kept.

That’s when I stopped lying to myself.

Morrison introduces the photographs Solidad took.

247 images of ledgers, passports, contracts, flight manifests.

Each one is entered into evidence with clinical precision.

Then she plays the wire recording.

Seven hours of audio condensed to 40 minutes of the most damning excerpts.

The jury listens to Rothstein explain his recruitment methods, his control mechanisms, his profit calculations.

They hear him discuss girls as products, inventory, assets.

They hear him order Solidad’s execution with the casual tone of someone ordering lunch.

When Rothstein’s voice says, “Take her to the desert and make it look like an accident.

” Solidad watches the jury’s faces.

Three women look like they want to vomit.

Two men are clenching their jaws so hard she can see the muscle working.

Even the ones trying to stay neutral can’t quite manage it.

The defense attorney’s cross-examination is vicious in that particular way of lawyers who know their client is guilty and have decided their only option is to destroy the witness’s character.

Miss Cruz, isn’t it true you were paid $50,000 by the FBI for your testimony? No.

I was given victim compensation for medical expenses after Dimmitri Vulov beat me and tried to murder me.

That’s not payment for testimony.

That’s compensation for being nearly killed while gathering evidence.

Isn’t it true you have a criminal record? I have a speeding ticket from 2009.

If that’s a criminal record, then yes.

Isn’t it true you continued working at the casino, continued serving drinks to these so-called criminals for months while you gathered evidence? This is the question designed to make her look like a collaborator rather than a victim.

Solidad takes a breath, meets his eyes.

Yes, I continued working there because Detective Martinez and the FBI told me we needed enough evidence to make sure Victor Rothstein never walked free.

I continued serving drinks to men I knew were raping girls my niece’s age because the alternative was moving too early and watching him escape justice.

I did what I had to do to save 17 women.

If that makes me complicit in the time it took to build this case, then I’m complicit.

But those women are free now.

And he’s sitting at that table facing life in prison.

So yes, I continued working there and I do it again.

The defense attorney tries a few more angles, but he’s lost the momentum.

When Solidad steps down, Morrison gives her a small nod.

You did well.

Over the next 3 weeks, the prosecution presents a case so comprehensive it feels inevitable.

Financial experts trace money flows from the LLC to Rothstein’s personal accounts.

$17 million over five years.

Immigration officials testify about the fraudulent visa applications.

FBI agents detail the rescue operation that freed 17 girls from the penthouse suites.

And then the victims testify.

Carmen, who thought she was coming to be a housekeeper.

Jasmine, given an American name because clients preferred the fantasy.

Isabelle, who spent two weeks in the basement discipline room for trying to escape.

11 women total, each one telling a story of recruitment through deception.

Control through debt bondage and violence.

Systematic rape by clients who paid Rothstein for access to women who couldn’t say no.

Sophia testifies on day 19.

She’s 20 years old now, but looks younger, fragile in a way that has nothing to do with physical size and everything to do with trauma.

She tells the jury about seeing the job advertisement for housekeeping supervisor, about needing money for her father’s kidney surgery, about arriving in Las Vegas with Hope.

She tells them about the first night when Rothstein’s assistant took her passport and explained that she owed $24,000 in recruitment fees, about being told that if she didn’t comply with specialized service requirements, her father would be arrested for visa fraud, about the 3 weeks where she was raped by between 40 and 80 men.

She’s not sure of the exact number because after a while, the days blurred together into one continuous nightmare.

When the defense attorney asks if anyone physically forced her to have sex, Sophia looks at him with eyes that have learned not to hope for justice from men in expensive suits.

No one held a gun to my head during the appointments, if that’s what you’re asking.

But Mr.

Rothstein kept my passport.

I owed $24,000 I couldn’t possibly repay.

His security chief, Dmitri, told me that girls who ran away ended up in the desert and their families ended up in prison.

So, no, I wasn’t physically forced in the moment.

I was trapped by debt and threats and fear.

If you don’t think that’s force, then you don’t understand what power is.

The defense rests without calling Rothstein to testify.

His attorneys know that putting him on the stand means the prosecution gets to cross-examine him with 7 hours of wire recording where his own voice condemns him.

Jury deliberation takes 4 hours.

The verdict is read on a Thursday afternoon.

The courtroom is packed with Filipino women, cleaning crews, and waitresses and housekeepers.

the invisible women of Las Vegas who came to watch one of their own win.

They fill the gallery in their work uniforms because they couldn’t take time off but came anyway on their lunch breaks.

On count one, human trafficking, we find the defendant, Victor Rothstein, guilty.

The words keep coming.

Guilty on all 47 counts.

Rothstein’s face doesn’t change, but his attorneys are already preparing appeals that will take years and ultimately fail.

Senator Blackwell guilty on 11 of 12 counts.

Judge Mendoza guilty on all eight.

Lieutenant Webb guilty on all 15.

The businessman guilty.

Guilty.

Guilty.

Sentencing comes 2 weeks later.

Rothstein gets life without parole plus 850 years consecutive.

The judge, a federal judge, not one of Rothstein’s purchased ones, looks at him and says, “You treated human beings as commodities.

You destroyed lives for profit.

You corrupted our institutions.

You will die in prison.

And that is more mercy than you showed your victims.

Rothstein is sent to ADX Florence, the Supermax prison in Colorado, where he’ll spend 23 hours a day in a concrete box.

Senator Blackwell gets 23 years.

Judge Mendoza gets 15.

Lieutenant Webb gets 18.

And the LVMPD opens an internal affairs investigation that eventually implicates 14 more officers.

The trafficking network collapses.

FBI raids 11 properties in seven states.

73 victims rescued, 104 arrests total.

But Victor Rothstein never makes it to ADX Florence.

3 months after sentencing, on a Tuesday morning in July, the federal transport vehicle carrying him to Colorado experiences catastrophic brake failure on Highway 95.

The vehicle crashes through a guardrail on a mountain pass, plunges 300 ft, and explodes on impact.

Rothstein’s body is identified through dental records.

The NTSB investigation concludes brake line corrosion caused the accident.

Detective Martinez attends the funeral.

His face is stone.

No one asks questions.

At the memorial service, a reporter asks him about rumors that the brake failure was suspicious.

Martinez looks directly at the camera and says, “Mr.

Rothstein’s death is a tragedy.

Justice should be served through the legal system, not through accidents.

My condolences to his family, but those who know him see the faintest smile at the corner of his mouth.

Some debts aren’t paid in courtrooms.

2 years after the trial, Solidad Cruz sits in a coffee shop in Henderson, a Las Vegas suburb far enough from the strip that she doesn’t have panic attacks from slot machine sounds, and she’s being interviewed by a journalist writing a book about the case.

The journalist asks her the question everyone asks.

Do you regret it? Solidad doesn’t answer immediately because the truth is complicated in ways that don’t fit into sound bites or neat narratives about heroism.

Her body never fully recovered.

The broken rib Dmitri gave her healed incorrectly and causes chronic pain that flares up when the weather changes or when she’s stressed, which is most of the time.

She has scars on her face from his fists that no amount of makeup fully conceals.

Her hands shake when she’s anxious, which is often a permanent tremor that makes holding coffee cups and exercise in concentration.

The psychological damage is worse.

She was diagnosed with complex PTSD, anxiety, and depression 6 months after the trial.

She has nightmares three or four times a week.

Sometimes she’s back in that SUV driving into the desert.

Sometimes she’s in the basement looking at files marked disposed.

Sometimes she’s just serving drinks at the Mirage Royale and every face is Dimmitri’s.

She takes medication that helps but doesn’t cure.

She goes to therapy three times a week with a trauma specialist who understands that surviving something doesn’t mean healing from it.

She can’t work in casinos anymore.

Can’t walk past slot machines without her heart rate spiking into panic territory.

Can’t smell cigar smoke without tasting vomit.

Can’t see security guards without her body preparing to fight or flee.

The FBI victim services coordinator helped her find work as a trafficking victim advocate, consulting with law enforcement and nonprofits.

But some days she can barely get out of bed.

The survivor’s guilt is a living thing that eats her from inside.

Why did she survive when Teresa didn’t? When Angela didn’t, when the nine girls marked disposed in Rothstein’s files didn’t, she made it out because she had Martinez and the FBI and luck and privilege.

She had family support.

She had legal status.

She had resources.

So many others had none of those things and they’re dead now.

Buried in the desert or disappeared into other trafficking networks or deported back to countries where they’re blamed for what was done to them.

Do I regret it? Solidad finally answers the journalist every single day.

Not because I wish I hadn’t done it, but because I wish it hadn’t been necessary.

I wish someone else had noticed those girls 3 years before I did.

I wish the system had been designed to protect them instead of protect their abusers.

I regret that it took my niece being trafficked for me to act.

I regret every day I stayed silent.

I regret that saving 17 women required nearly dying.

And I regret that I’m one of the lucky ones because I survived and so many others didn’t.

The journalist scribbles notes, then asks the follow-up.

But would you do it again? Solidad thinks about Sophia, who moved back to Manila after the trial and spent two years in intensive trauma therapy and eventually enrolled in university to study social work.

She runs a nonprofit now that helps trafficking survivors reintegrate into society.

She still has nightmares, still has triggers, still has days where the weight of what happened crushes her, but she’s alive and free and fighting to save others.

She thinks about the 16 other women freed from those penthouse suites.

Nine stayed in the US on TV visas.

Seven returned to the Philippines.

all received victim compensation, $50 to $100,000 each, which doesn’t come close to compensating for what was taken from them, but at least acknowledges their suffering in the only language capitalism understands.

Most are in therapy.

Some are thriving, some are surviving, some are barely holding on.

But they’re all alive and they all have choices now.

And choice is everything when someone has spent months as property.

She thinks about the 14 LVMPD officers who were fired or prosecuted after the internal affairs investigation revealed the depth of corruption protecting Rothstein’s operation, about the new anti-trafficking protocols that Nevada implemented, the mandatory training for law enforcement and casino employees, the hotline posters in bathrooms in 12 languages.

She thinks about the emails she gets from Filipino women working in Las Vegas casinos.

Women who tell her that knowing her story makes them feel less invisible, less powerless, less alone.

Women who’ve reported suspicious activity because they learned that sometimes fighting back is possible.

Yes.

Solidad tells the journalist.

I do it again because 17 women are free and Rothstein died in prison and the system that protected him got exposed.

That matters.

But the truth she doesn’t say, the truth she barely admits to herself is that she’s not sure she survived either.

Not in any meaningful way.

Yes, her body is still breathing, still functional.

But the woman she was before, the one who believed that if you kept your head down and worked hard enough, you’d be okay.

She died that night in the desert when Dimmitri pressed his gun to her forehead.

The woman who came back is harder, colder, perpetually angry at a world designed to grind up people like her and call it opportunity.

She doesn’t trust authority.

She doesn’t believe in justice without pressure.

She understands that the only thing protecting the powerless is making powerful people more afraid of consequences than they are confident in impunity.

Solidad Cruz is not a hero.

Heroes are people who make brave choices.

She made the only choice available after every other option was eliminated.

That’s not bravery.

That’s just being cornered.

The Mirage Royale Casino still stands.

It was sold after Rothstein’s assets were seized, rebranded as the Oasis Resort and Casino, given a multi-million dollar renovation that erased any physical evidence of what happened in those penthouse suites.

The new owners implemented strict anti-trafficking protocols, security trained to recognize coercion indicators, hotline information in employee bathrooms, quarterly labor audits.

is better than before, which is a low bar.

But the girls still pour drinks on the casino floor, still wear tight dresses and plastic smiles, still navigate hands on waists, and men who treat service workers as disposable.

The structure hasn’t changed, just the specific faces filling those roles.

Solidad went back once, 6 months after the trial, because her therapist thought confronting the space might help with the nightmares.

Didn’t.

She made it as far as the lobby before the panic attack hit.

hyperventilation, tunnel vision, her body convinced that Dmitri was coming around the corner.

Martinez had to walk her out to the parking garage where she vomited and cried and understood that some spaces are permanently contaminated by trauma.

But something did change.

Rosa and Maria, who still work cleaning crew, told Solidad that the Filipino workers whisper her name now, not as a person, but as a promise.

When new girls arrive, confused and frightened and not sure if what’s happening to them is legal, the older women pull them aside and tell them Solidad fought back.

Soladad nearly died fighting back and Solidad won.

It’s become a form of resistance mythology which embarrasses Solidad because the mythology ignores how close she came to losing, how much luck was involved, how many privileges she had that other women don’t.

But she understands its function.

Invisible people need to believe that visibility is possible.

Powerless people need to believe that power can be challenged.

And women who’ve spent their lives being told their disposable need to believe that their lives matter enough to fight for.

Solidad’s mother lives with her now.

The FBI victim compensation fund paid her medical bills and covered the cost of bringing her to America on a family reunification visa.

Elena Cruz is 73 years old.

Her heart condition managed with medication they can actually afford now.

She spends her days in Solidad’s small house in Henderson, cooking food that tastes like home, praying her rosary, watching Filipino television on a satellite dish.

Sometimes Elena looks at her daughter with an expression Solidad can’t quite read.

Pride mixed with grief, satisfaction mixed with guilt.

She knows Solidad saved Sophia.

She also knows the cost.

One night, 6 months after she arrived, Elena told her daughter in Tagalog, “I prayed for you to succeed in America.

I didn’t know success would require this much sacrifice.

If I could take back those prayers and keep you safe instead, I would.

Solidad told her she wouldn’t.

That safety purchased with other people’s suffering isn’t safety at all.

Just a comfortable form of damnation.

Her brother Miguel finished university and works as an engineer now in Manila.

His wife knows what happened to their daughter, but doesn’t talk about it except in therapy sessions they do together.

Miguel calls Solidad every Sunday and the conversations are always strained because they both know his daughter’s freedom cost his sister’s peace of mind and there’s no way to acknowledge that debt without it becoming unbearable.

Sophia and Soladad video call every week.

Sophia looks healthier now.

She’s gained back the weight she lost during those three weeks of captivity.

The light in her eyes isn’t completely extinguished anymore.

She tells her aunt about the women her nonprofit helps, about the small victories of getting someone into safe housing or therapy or legal assistance.

But Solidad also sees the shadows that cross Sophia’s face when she thinks her aunt isn’t looking.