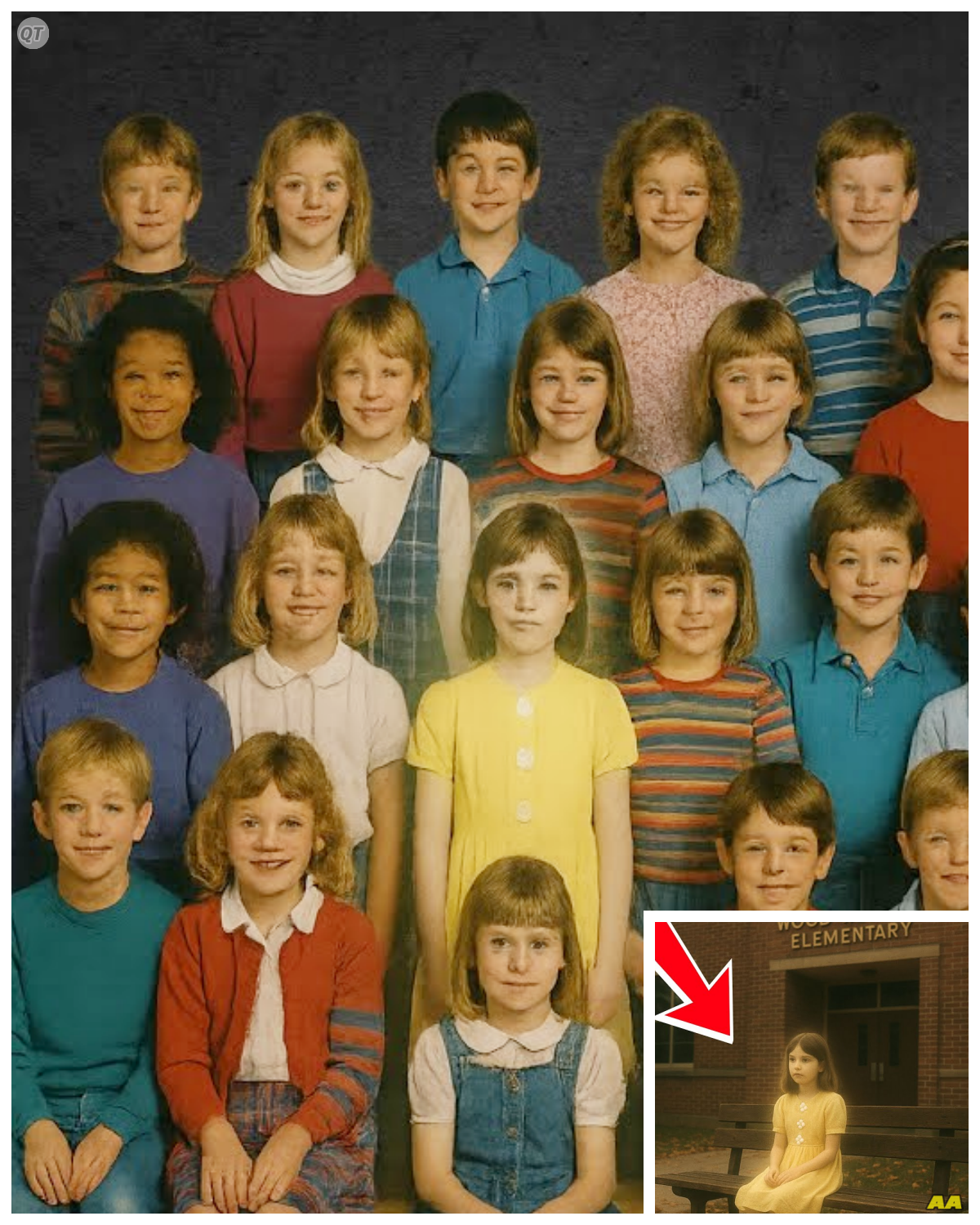

In the fall of 1993, a second grade girl walked into her elementary school in suburban Minnesota, smiling in her favorite yellow dress.

It was school picture day.

By 2:15 p.m., she was gone without a trace.

For decades, her parents clung to hope.

Then, in 2023, a retired school photographer discovered an undeveloped role of film in his basement.

What he developed would send the entire town into a nightmare they thought was buried.

Subscribe for more chilling true crime mysteries based on real events.

New stories every day.

November 12th, 2023.

Location, Wood Hollow, Minnesota.

72-year-old Martin Kellerman hadn’t touched his basement dark room in nearly 15 years.

But when his wife passed, cleaning it felt like a step toward closure.

As he rummaged through boxes marked archive 1993, he found an old roll of Kodak gold film still in its canister.

He nearly tossed it, but habit made him develop it.

The faces appeared one by one, rowdy class clowns, shy smiles, missing teeth, and then one final frame.

The girl in the yellow dress, eyes wide, looking off camera, terrified, and just behind her, a hand.

October 5th, 1993.

Location: Wood Hollow, Minnesota.

The morning bell rang at 8:00 a.m.

Sharp, echoing through the brick hallways of Wood Hollow Elementary.

Outside, the October sky was a pale, washed out blue, and the maple trees lining the school’s front yard had already started to shed their leaves.

Yellows and reds fluttered to the ground with every breeze, crunching beneath the small, eager feet of second graders rushing inside with backpacks too big for their frames.

Class 2B was buzzing with energy.

Picture day always brought out a strange mixture of pride and nervousness in the kids.

clean shirts buttoned all the way up, barretes and headbands tugged too tight, collars poking awkwardly from sweaters.

Miss Taland, a young teacher in her second year, had done her best to keep the chaos to a minimum, but the energy was impossible to contain.

Everyone, coats on hooks, backpacks zipped, and please, for the love of Kevin, stop licking the window, she called from her desk, flipping through the photographers’s schedule.

They’ll be calling us down soon.

In the corner of the room, seated at desk number 14, was Meline Harper, 8 years old, brown hair just past her shoulders, gap between her front teeth, dressed in a yellow cotton dress with daisy buttons her mother had sewn on herself.

She was quiet, always had been, but especially today.

While the rest of the class laughed and swapped combs, Meline stared at the clock above the chalkboard.

Her small hands were folded tightly in her lap.

Miss Taland noticed.

Meline, you doing okay? Meline nodded but didn’t smile.

Her desk was neat as always.

Composition notebook on the left, schoolisssued crayons in the plastic container on the right.

But there was no lunchbox, no sweater.

She hadn’t taken her usual seat on the rug during morning circle time either when Miss Talin glanced at the attendance sheet.

Meline’s name was checked off.

Checked off by someone.

The photographers’s assistant poked his head into the classroom around 9:15.

2B.

We’re ready for your class.

Miss Taland clapped twice.

All right, line up quietly, please.

Alphabetical order.

The kids groaned but obeyed.

They filed down the hallway, shoes squeaking on the lenolum toward the makeshift portrait setup in the school’s multi-purpose room.

Folding chairs, a wrinkled gray backdrop, a long table of props no one was allowed to use.

Martin Kellerman, the photographer, graying hair, stained polo shirt, was adjusting the lighting umbrella, his old Canon AE one on a tripod before him.

Class 2B, he called cheerfully.

Let’s get those smiles ready.

Meline was third in line.

The assistant checked her name on the list.

Meline Harper, number three, yellow dress.

Second grade.

She stepped onto the tape mark on the floor.

Martin peered through the viewfinder.

Sit up straight.

Chin down.

Little smile.

Click.

Flash.

She blinked at the light.

Her lips didn’t quite form a smile.

Something in her expression.

wide eyes, shoulders drawn tight, gave the assistant pause.

Martin clicked twice more.

“We’ll use the second one,” he muttered.

She stepped off the mark and then she was gone.

11:38 a.

m.

Recess bell rang.

Half the class was outside, half was finishing lunch.

Meline was nowhere.

Miss Taland asked around, “Has anyone seen Meline?” The answers came slow.

No one remembered seeing her after pictures.

No one remembered her on the playground.

Maybe she went to the nurse, someone offered.

She wasn’t there.

Maybe she went home sick.

No one had called her out.

By 12:15, the office confirmed her absence.

A schoolwide search began by 12:30.

Every classroom, every restroom, every janitor’s closet.

They even searched the library’s reading tent in the AV storage cage in the basement.

By 1:15, her mother had arrived, pale, crying, still wearing scrubs from her shift at the urgent care.

By 2:00 p.

m.

, the police had blocked off every exit.

Lockdown initiated.

By 4:45 p.

m.

, the sun was sinking behind the trees, and Maline Harper was officially declared missing.

Present day 2023.

The photograph had never been delivered.

Not to her family, not to the school’s yearbook.

Somehow, it slipped through the cracks, and 30 years later, it would be the final image on the film roll found in Martin Kellerman’s basement.

Frame 24.

Maline Harper, eyes wide, mouth slightly open, and just behind her, in the shadows of the backdrop, a hand resting on her shoulder, one that didn’t belong to the assistant, the teacher, or anyone accounted for.

October 5th, 1993.

Afternoon.

Location: Wood Hollow Elementary, room two.

The school nurse, Mrs.

Lantham, was the first to voice what no one else wanted to say.

She’s not here.

Not in the nurse’s office, not with the secretary, not walking the halls clutching a bathroom pass.

Not in the lunchroom, the library, or curled up in the reading loft with a book about fairies like she sometimes did when her stomach hurt.

By 12:22 p.

m.

, Meline Harper was gone.

Miss Talin stood in the hallway, clipboard pressed to her chest, her mouth dry.

A sour taste clung to the back of her throat, but she kept her composure as Principal Riggs arrived.

“What’s going on?” Riggs asked, breath heavy from the stairs.

“She never came back from pictures,” Miss Talin said.

“I thought maybe she went to the nurse or the library, but I’ve checked everywhere.

” Principal Riggs nodded.

“Let’s not panic.

We’ll check again.

I’ll alert the staff.

He moved quickly toward the main office, shoes pounding against the tile.

Moments later, the PA crackled to life.

Faculty and staff, please check your classrooms, bathrooms, and any common areas for a student.

Maline Harper, second grade, brown hair, yellow dress.

Last seen this morning during picture sessions.

This is not a drill.

In room 2B, her desk remained exactly as she’d left it.

Her pink plastic lunchbox still sat unopened inside the cubby, filled with a peanut butter sandwich and an apple juice pouch.

Her backpack hung on the hook beside her desk, zipper slightly open.

Her My Little Pony folder peaked out from inside.

A single crayon, burnt orange, lay next to her math worksheet on the desktop, as if dropped midpro.

The children had grown quieter, the buzzing energy of picture day now replaced with a strange, confused silence.

Some whispered, others stared at the empty desk.

Kevin, the loudest of the bunch, now sat hunched, chewing a loose thread on his sleeve.

“Where’d she go?” asked Andrea, voice barely above a whisper.

No one answered.

12:55 p.

m.

Officer Susan Ryland arrived first.

She’d grown up in Wood Hollow, graduated from the same elementary school in 1979, and had worn the same faded blue uniform for 12 years.

She was a mother herself, two boys, ages 10 and 14, and her face tightened when she saw the empty desk and Miss Talin’s ashen expression.

She was here this morning.

Yes, Miss Talin said, third in line.

She sat for her picture and then I assumed she was with the group.

I didn’t notice she’d gone until lunch.

No one saw her leave.

Not that I know of.

We were all being shuffled around.

Kids were moving in and out.

It’s chaotic on picture day.

Ryland nodded.

Was there a sign out? A visitor log? Principal Riggs approached.

We’ve checked.

No parents signed her out.

The front door camera didn’t catch anything.

But it’s motion activated.

It only records when someone walks within 5 ft.

And the side doors were propped open earlier for deliveries.

Jesus, Ryland muttered under her breath.

Do you have recent photos? I can give you last year’s school portrait, Rig said.

We’ll get it copied.

Pull the list of staff, subs, maintenance, anyone not normally here today.

I’m already on it.

1:15 p.

m.

Meline’s home.

Valerie Harper stood on the front lawn in her blue scrubs, pacing.

Her name badge, V.

Harper, RN, shimmerred in the sun.

Her husband hadn’t arrived yet.

He worked construction and had to drive in from Duth.

She didn’t come home, Valerie kept saying, voice rising in panic.

She’s never late.

She always calls from the office if there’s a delay.

Where is my daughter? Officer Ryland walked beside her gently.

We’re doing everything we can.

Right now, we’re treating this as a potential missing person situation, not an abduction.

Not yet.

She may be hiding, lost, confused.

It’s happened before.

She’s not the kind of wander.

Valerie snapped.

She’s shy.

She sticks close to teachers.

She’d never I know, Ryland said.

We’re going to find her.

Valerie turned to the house.

Her room’s upstairs.

She slept fine.

No signs she planned to run.

She was excited about picture day.

We curled her hair.

She picked the yellow dress herself.

Ryland followed her inside.

The bedroom was neat.

Bed made, stuffed animals lined across the pillow.

On the desk sat a school note addressed to parents.

Picture day, October 5th.

Please arrive.

Camera ready.

Pinned beside it was Meline’s favorite drawing.

a sketch of a white horse with wings flying over a hill.

Beneath it, she’d written in purple marker, “I want to fly away, but only if mommy comes, too.

” Ryland stared at the note for a long moment.

2:45 p.

m.

The woods.

By late afternoon, volunteers had joined police officers in a full-scale search.

Parents, teachers, teens from the nearby high school.

They combed the woods behind the playground in loose grid patterns, calling Meline’s name.

The area was dense, sloped downward toward a marsh.

In autumn, visibility was low.

Fallen leaves blanketing everything.

Brittle branches snapping underfoot.

A K9 unit sniffed along the southern trail, but caught no scent, no blood, no shoe, no signs of a struggle.

It was as if she’d evaporated.

The only thing found was a scrap of yellow fabric caught on a low branch, but it didn’t match Meline’s dress.

It was older, weathered, likely trash.

The Woods gave up no secrets that day.

3 p.

m.

Police report.

Initial summary.

Missing child report.

Name: Maline Marie Harper.

Age 8.

Height 4’1 in hair.

Brown shoulderlength eyes, hazel clothing, yellow dress with daisy buttons, white socks, black Mary Janes.

Last seen 9:15 a.

m.

during school picture day at Wood Hollow Elementary.

Witnesses: None confirmed.

Potential risks.

Side doors open during delivery.

No cameras inside the multi-purpose room.

Substitute janitor working that day.

Case status.

Active missing child investigation.

Present day 2023.

The desk remained.

Room two.

B had changed over the years.

New carpet, a smartboard replacing the old chalkboard, but the desk had been pushed into storage rather than tossed.

Martin Kellerman’s photo, now developed, sat on the desk in a clear plastic sleeve.

Detective Amy Salvon stood over it.

her heart hammering.

She had been in third grade when Meline vanished.

Her classroom was just down the hall.

She remembered the lockdown, the crying teacher, the empty seat at lunch.

But she didn’t remember this photo.

Meline frozen in the moment, hair curled, mouth slightly open, eyes wide with something not quite fear, more like dawning realization.

And behind her, partially obscured by shadow, a hand on her left shoulder, thumb burned and shiny, scarred.

Whoever it was never looked at the camera.

They didn’t have to.

November 13th, 2023.

Location: Wood Hollow, Minnesota.

Martin Kellerman hadn’t touched a camera in 15 years.

He’d boxed them up in 2008.

the Canon AE1, his tripod, the lighting umbrella with a burnhole from the 1986 gym fire.

All of it sealed in a basement cabinet alongside old negatives and yellowed appointment logs.

After his stroke and after the divorce, he told himself he was finished with all of it.

No more shutter clicks, no more squinting through fogged lenses, and certainly no more picture days.

But when his wife died in August, everything changed.

Now 3 months into widowhood, he stood in the shadows of his basement dark room.

Fluorescent lights buzzed overhead.

The air smelled of dust, vinegar, and expired developer fluid.

He moved slowly, dragging a stool beside the film dryer, hands trembling from age more than nerves.

The roll of Kodak Gold 200 had been in an unmarked envelope, taped shut, tucked inside an old yearbook box.

1993 Wood Hollow Elementary.

Martin didn’t remember ever forgetting a roll, but when the first images appeared in the chemical bath, it all came rushing back.

Frame one.

A little boy named Christopher Meyers missing his front teeth making rabbit ears behind his own head.

Frame two.

Twins in matching dresses.

Emily and Kayla.

Frames 3 to 22.

Faces he couldn’t name but vaguely remembered.

Cowix, oversized glasses, tight shouldered cardigans.

Then came frame 23.

A blank shot.

An accidental click probably.

and then frame 24.

He knew before the full image appeared that something was wrong.

Present day 10:42 a.

m.

Wood Hollow Police Department evidence room.

Detective Amy Salvis sat across from Martin in a private conference room.

The photograph lay between them on the table encased in an archival sleeve.

He hadn’t wanted to bring it to the station.

He had planned to throw it away, but he couldn’t.

Martin had called the tip line the night before.

Left a voicemail around midnight.

I developed an old role from Wood Hollow Elementary.

It’s a portrait, a girl.

I think it’s her.

I think it’s Meline Harper.

I don’t know how I forgot or if I ever even saw it back then, but someone else was there in the frame.

Someone I don’t remember.

Now here he sat, hands folded, cane resting between his knees, his voice low and brittle.

“I don’t remember taking it,” he said, staring at the image.

“But I must have.

That’s my camera, my light, the setup.

That was me.

” Detective Salvis leaned forward.

“Tell me about that day.

Anything you remember?” Martin exhaled.

October 5th, 1993.

I did four schools that week.

Two classes per school, staggered every hour.

Wood Hollow was the second.

I was running late.

My assistant, Ed, was supposed to meet me there, but he didn’t show.

Why? He had the flu.

Called in that morning, so I was alone.

Do you remember Meline Harper specifically? He shook his head.

Number, but I never really remembered the kids by name.

They were just a line of smiles.

Sit.

Click.

Next.

Salvon tapped the photograph.

But this one doesn’t look like the others.

Look at her expression.

I know, Martin whispered.

In the photo, Meline sat straight back, her lips slightly parted, eyes locked somewhere just past the lens.

Not at the photographer.

That’s something else.

I think she saw whoever was behind her, Martin said.

Salvon nodded.

Let’s talk about the hand.

The hand rested on her shoulder gently, almost fatherly, but wrong.

The thumb and index finger were scarred.

Skin tight and glossy like melted wax burned.

There was no sleeve visible.

No shirt cuff.

Just the hand floating in frame connected to someone outside the camera’s view.

Martin looked ill.

I don’t know how I didn’t notice it.

Or maybe I did and forgot.

It’s possible with a stroke.

Things got scrambled.

“You have any idea who that might be? Anyone who might have had access to the room?” “No one was supposed to be there but me and the kids,” he said, voice shaking.

“But that day was chaos.

The gym had flooded, so they moved us to the multi-purpose room.

The custodian came in twice to move a mop bucket.

There was a substitute teacher who didn’t check the roster, right? I just remember trying to get through it.

Do you remember anyone unusual? Any adults who didn’t belong? Martin paused.

There might have been a man.

Late 40s, thin.

Stood by the door for a while.

Didn’t speak.

I thought maybe he was a parent.

I was busy.

It didn’t register.

You didn’t question it.

I didn’t think I had to.

It’s a school.

People come and go.

Salvon wrote it all down.

Her stomach twisted.

Do you think this was someone from the staff? She asked.

Martin’s voice dropped to a whisper.

I don’t think this person was supposed to be there at all.

Later that afternoon, Wood Hollow Elementary, now Wood Hollow Community Center.

The old multi-purpose room still existed, repurposed as a dance studio with mirrors on every wall, but the layout hadn’t changed much.

Salves walked the perimeter, letting the details come back.

The backdrop used in the photo shoot had been a gray muslin cloth, usually hung from a portable frame.

In frame 24, the backdrop was pulled slightly off to the side.

A visible crease exposed the drywall behind it.

She zoomed in on the photo on her tablet.

Behind Meline’s left shoulder was not just the hand, but the faint curve of a doorway, a door that wasn’t on the current blueprints.

Salvon circled back to the old maintenance plans stored in city records.

And there it was, a narrow janitor’s closet once positioned behind the stage partition.

It had been sealed off sometime around 1997.

She called it in.

Get me a forensics team.

Gloves, lights, cutting tools.

I think we just found the first crack in a 30-year-old wall.

November 14th, 2023.

location.

Wood Hollow Police Department detective Amy Salvas had seen her share of cold cases.

Files faded with time.

Statements written in cursive.

Photos stained from handling.

Reports that said nothing unusual when everything about them was wrong.

But case file 93,1005 wasn’t just any cold case.

It was personal.

She was seven when Meline Harper disappeared.

They’d never met, not really.

But they’d passed each other in the hallway, brushed sleeves in the lunch line.

In a town like Wood Hollow, every missing child feels like your own.

Now, 30 years later, the file sat in front of her, a cracked beige folder with bent corners and a red unsolved sticker across the top.

Amy opened it carefully.

The first photo inside was Meline’s second grade portrait from the previous year.

The last officially developed image of her before frame 24.

She smiled shily, head tilted slightly as if unsure how to hold her body.

Her eyes were the same, software open, trusting.

Underneath was a timeline.

October 5th, 1993.

9:15 a.

m.

Meline photographed.

10:45 a.

m.

Not present at snack break.

11:30 a.

m.

Teacher notices absence.

12:15 p.

m.

Schoolwide search initiated.

2:00 p.

m.

Officially reported missing.

400 p.

m.

Police K9 unit dispatched.

October 6th to 9th.

Extensive search of school grounds nearby Woods neighborhood canvasing.

October 15th, 1993.

FBI consulted.

No evidence of federal jurisdiction.

Case remains local.

December 1993.

Active search scaled down.

No viable leads.

Case goes cold.

Beneath the timeline was a list of suspects.

Most were ruled out.

Parents cleared.

Teachers interviewed.

No criminal history.

Custodian.

Present that day.

Died in 2002.

Temporary staff.

Substitute PE teacher.

no longer employed.

Delivery driver alibi confirmed.

School photographer cleared at the time.

Then a line highlighted in orange.

Unknown adult male seen loitering near the auditorium during photo sessions.

Description vague.

Not found during campus sweep.

Amy read that line twice.

3:24 p.

m.

Evidence processing room.

Salvon stood in front of the bulletin board where her team had pinned up a highresolution print of frame 24.

Meline’s photo had been enlarged, lightened, adjusted for contrast.

The hand on her shoulder, once vague, now showed clear scar tissue along the knuckles, a deep crease in the palm, the skin around the thumb glossy and stretched, likely from an old severe burn.

Forensics estimated it was at least 20 years old at the time the photo was taken.

That meant the man, whoever he was, had likely been injured in the late 70s or early 80s.

Salvon circled the detail in red marker.

One of her officers, Lexi Duran, stepped into the room holding a yellow envelope.

Just got the original attendance log from the school district archives, 1993.

Written in pencil on a yellow legal pad.

You’re going to love this.

Amy opened it and scanned the names.

Each student was listed with a check mark beside their name dated October 5th.

Maline Harper checked in and under staff present.

Someone had written Mr.

Blaine, subcustodian, temp agency.

Amy’s brow furrowed.

Blaine? That’s not a name in the official personnel file.

Nope.

Lexi said.

We checked the 1993 district payroll.

No one by that name.

Not for that year or any year.

Salvon turned back to the board.

So, who wrote him in? 5:41 p.

m.

Interview room 3.

Miss Abigail Taland had aged, but not badly.

Her hair, once mouse brown and pinned with pencils, was now stre with white.

She wore a soft cardigan, glasses, and grief like a second skin.

30 years hadn’t dulled the way her mouth tightened when she said Meline’s name.

I remember it like it was yesterday, she said softly.

She was there that morning.

Yellow dress.

She curled her hair just slightly.

She told me she wanted to look like the sun.

Salvon nodded.

And after pictures, I assumed she went to lunch or the nurse or I don’t know.

You always think you’ll see them again.

You don’t count heads like you should.

Not on a day like that.

Do you remember a custodian named Mr.

Blaine? Miss Talin blinked.

That sounds familiar.

Tall man, thin, quiet.

We don’t have a file on him.

He wasn’t a district employee.

Her hands trembled in her lap.

Then where did he come from? That’s what we’re trying to find out.

6:30 p.

m.

Wood Hollow Community Center, formerly the elementary school.

The forensics team had removed the mirrored paneling in the old multi-purpose room, revealing the wall behind it and the faint outline of a door, now sealed with drywall and studs.

Amy ran her fingers across the edge.

Start cutting, she told them.

A rotary saw winded to life.

Dust plumemed into the air.

Amy stepped back as the team sliced along the seams.

After 15 minutes, the cutout section fell forward with a thud.

Behind it was a narrow space 4 ft wide, 8 ft deep, a closet, forgotten by time.

Inside was nothing but dust, and a small pile of rusted cleaning supplies, a cracked mop handle, two empty buckets, a faded calendar still stuck to the wall, curled and yellowed.

The date at the top, October 1993.

One date was circled in red ink.

Tuesday the 5th, present day, 9:12 p.

m.

Back at the station, Amy stared at the name written in faded cursive inside the calendar.

Not Blaine.

CR Taland.

Her mind stumbled.

Taland.

She flipped through her own notes.

Abigail Taland, second grade teacher, never married, lived alone, still in town.

Amy picked up her phone and called officer Duran.

Lexi, I need you to run a deep search.

Look into Miss Taland, family members, siblings, especially anyone with a criminal past.

Copy that.

Amy leaned back in her chair, her eyes wandered to the photo of Meline, the slight tremble in her jaw, the stare just off camera.

She hadn’t been looking at a stranger.

She had recognized something.

Someone.

It wasn’t just fear in her eyes.

It was betrayal.

November the 15th, 2023.

Location, Wood Hollow Police Department.

The call came just after midnight.

Officer Lexi Duran’s voice came through the phone, low and steady.

I found something.

Miss Taland had a brother.

Real name Caleb Russell Taland.

Born 1954.

arrested in 1982 for attempted abduction of a minor in Duth.

Charges were dropped.

Child refused to testify.

No conviction.

But it’s him, Amy.

He’s our mystery custodian.

Amy sat up in bed, heart pounding.

Where is he now? Nowhere on record since 2006.

Last known address was a trailer lot in St.

Louis County.

DMV records expired.

no recent employment, but he used the alias Blaine Carter on several job applications back in the early 90s, including one temp agency that sent school custodians to Wood Hollow.

So, there it was.

Maline Harper’s suspected abductor hadn’t been a stranger.

He’d been the brother of her teacher, and someone had gone to great lengths to erase him from the system.

8:35 a.

m.

Wood Hollow Elementary Archives, District Office.

Amy stood in the school district’s climate controlled record room, breathing in the dry scent of paper and time.

Row after row of labeled boxes stretched to the ceiling.

A district secretary wheeled over a metal step ladder.

“Everything from the ’90s is boxed by month in school,” she explained.

But some of it was water damaged in the 2005 leak.

That section’s incomplete.

Amy climbed the ladder, her fingers tracing faded labels.

Wh-elempptember-93 Wh-m October-93 WH-Elem November-93.

She pulled the October box and set it on the metal cart.

Inside were permission slips, memos, substitute logs, visitor records.

But someone had been careless or deliberate.

Pages were missing, torn.

Amy found the October 5th visitor log, folded awkwardly and stained with something brown.

Half the sheet was gone, ripped clean through where the signatures began.

The top remained.

Wood Hollow Elementary.

Visitor sign-in log.

Date: October 5th, 1993.

Please print your full name and purpose of visit.

The rest was missing.

The names, the times.

Whoever signed in that day, if anyone did, was now erased.

9:47 a.

m.

Interview room 2.

Miss Abigail Talin didn’t flinch when they brought her back in.

She wore a pale lavender coat, carried a small leather purse.

Her hair was pinned back with the same gold barret she’d worn in her staff photo from 1993.

“Why am I here again?” she asked, settling into the chair.

Amy set the manila folder down gently.

“You said last time you didn’t remember the custodian that day, Mr.

Blaine.

” I didn’t, she replied.

Amy opened the file and pulled out a photocopy of the visitor log, then the calendar page from the sealed janitor’s closet.

This is your brother’s handwriting, isn’t it? Miss Taland’s lips thinned, but she didn’t answer.

Caleb Taland, arrested in 1982, used the name Blaine Carter when applying for jobs.

You vouched for him with a temp agency, didn’t you? Silence.

Amy leaned forward.

He wasn’t just loitering that day.

He signed in.

He had keys.

He had access.

Did you know he was there? Miss Talin swallowed.

He said he just needed work.

That he’d cleaned himself up.

That it was one day, one shift.

He promised.

You didn’t tell the police.

I couldn’t, she whispered.

They would have fired me.

the school, the district, and I thought he’d left before lunch.

I never saw him with her.

Amy’s voice sharpened.

You wrote him in on the attendance sheet.

Talin’s eyes filled, but she said nothing.

You knew maybe not everything.

Maybe not what he planned, but you knew he shouldn’t have been there.

And you helped him anyway.

I thought she was just missing, Talin said, voice cracking.

I thought maybe she ran away.

I didn’t think he she stopped herself.

What did he call her? Talin’s eyes darkened.

Princess, she whispered.

He called every little girl that.

12:16 p.

m.

Police lab evidence processing.

Amy stood beside the forensic tech as they examined the highresolution scans of frame 24.

Again, the team had enhanced the image using AI reconstruction and spectral analysis.

Behind the hand, in the blurred shadows near the edge of the frame, was something else.

A vertical crease, not a wall, a curtain, the kind used on rolling dividers in older schools.

Behind that, a faint outline, rectangular, flat, metallic.

Amy leaned in.

Is that a handle? Could be.

The text said, “We think this may not be just a closet behind the multi-purpose room.

We think there’s something behind that closet.

A second room, a storage chamber, maybe, but it’s not on the blueprints.

” Amy’s stomach dropped.

Get me the ground penetrating radar today.

2:05 p.

m.

Wood Hollow Community Center.

The old school creaked beneath Amy’s boots as she and the forensics team returned to the multi-purpose room.

The drywall was gone.

The old janitor’s closet stood exposed, now lit with portable LED towers.

But the team wasn’t interested in the closet anymore.

They were interested in the wall behind it.

GPR scans had confirmed it.

A rectangular chamber 6×10 ft tucked between structural supports.

a sealed space hidden for 30 years.

The lead tech pointed to the hollow cavity.

We’re going in.

Two officers began chiseling through the back wall of the closet.

The concrete crumbled slow, deliberate.

Dust clouded the room.

Amy watched from the side, pulse pounding.

The chisel struck metal, then air.

Then came the smell.

Old, dry, sour.

One of the texts gagged.

Another officer shined a flashlight through the hole.

His voice dropped to a whisper.

“Ma’am, you need to see this.

” They widened the opening.

The hidden room was small, barely wide enough for one person to sit or lie down.

No windows, no ventilation.

Foam insulation lined the walls.

A single pink blanket lay bunched in the corner and in the center a disposable camera wrapped in a sandwich bag labeled in black marker property of princess.

Do not touch.

Amy took a shaky breath.

Bag it.

Get it to the lab.

The officer bent down to collect the camera.

As he did, his flashlight caught something else.

Scratched into the foam wall behind the blanket.

Tiny fingernail markings over and over the same word.

Help.

November 16th, 2023.

Location, Wood Hollow Police Department, Forensics Division.

The lab was silent except for the soft clicks of plastic gloves and the occasional beep of an aging scanner.

Detective Amy Salverson stood over the evidence table where the disposable camera found in the sealed chamber behind the multi-purpose room now rested.

It had been carefully extracted from the bag it was stored in.

Dried, dusted, and cataloged.

Films intact, the forensic tech confirmed.

Slight moisture damage on the casing, but nothing serious.

Lucky it was wrapped.

How many exposures? 27, he said, and all were used.

Amy felt a chill.

27 photos shot inside a 6×10 ft cell no one knew existed.

3:42 p.

m.

Photo lab development room.

They used traditional chemicals.

No digital shortcuts.

This film had been sitting for 30 years.

It deserved precision.

One image at a time, the negatives emerged.

The first was grainy.

Dim lighting, pink insulation behind a child’s head.

Meline.

Amy’s breath caught.

Her eyes were red rimmed.

Her hair slightly tangled.

But she was alive, awake, sitting cross-legged, holding a plastic cup with a juice box straw poked through the top.

Frame after frame showed the same.

Her in different positions, sometimes smiling faintly, sometimes curled up.

a child surviving.

Some frames were darker, others were blurry, but a story was taking shape.

In frame 19, something changed.

The girl wasn’t alone.

A hand extended into the frame, holding a small plastic tiara.

Meline stared at it blankly.

Frame 20.

She wore the tiara.

Frame 21.

A man entered frame, barely visible.

just a silhouette reflected in the glass of a turned off TV screen behind her.

But the hand was unmistakable, scarred, shiny, burned.

Amy’s stomach clenched.

7:18 p.

m.

Police Station briefing room.

The images were projected one by one for a select task force, detectives, forensics, and child welfare.

Amy stood at the front, clicking through the sequence.

This camera was found behind the false wall of the janitor’s closet inside a concealed chamber we believe was used to detain Meline Harper on the day of her disappearance.

She paused at frame 23.

Meline was seated in the far corner of the room, tears streaming down her face.

The pink blanket pulled tightly around her.

A word was scrolled behind her on the foam wall, faint but visible.

Princess frame 24.

A closeup of her face, eyes glassy, resigned.

In her hands, she held a folded note card.

A faint red stain ran across the front of her yellow dress.

The forensics tech zoomed in.

“Blood,” he confirmed, likely from a nose bleed or minor injury, but it dried fast.

Frame 25 was blank.

Frame 26 showed a shadow moving past the camera.

Frame 27 was completely black, possibly the camera placed face down or snapped unintentionally.

Amy turned to the group.

We now believe Meline was alive in this space for at least several hours, possibly overnight.

The room was designed for short-term concealment.

No plumbing, no food storage, no waste disposal.

Someone intended to move her.

“Do we have a DNA profile from the blood?” asked one of the analysts.

“Preliminary swabs underway.

We’ll compare it to her family.

” Amy pointed to the blurry reflection in frame 21.

We’ve enhanced this still.

Facial details are obscured, but we’ve confirmed the man’s height is approximately 5′ 11″ in.

Right-handed, severe burns on left hand and wrist.

same as our hand in the original school portrait,” someone murmured.

Amy nodded.

“We’re dealing with one offender, possibly two.

” She clicked off the projector.

“And he never planned to keep her there, which means she was moved somewhere else.

” 9:05 p.

m.

Harper residence.

Valerie Harper opened the door in a bathrobe.

Her hair was damp, her eyes, tired and worn, held the same cautious hope she’d carried for 30 years.

“You have something,” she said before Amy even spoke.

“Yes,” Amy replied gently.

“We found a camera.

” Valerie covered her mouth.

“We believe Meline used it, possibly to document where she was.

” “Is she in the photos?” “Yes.

” Valerie blinked away tears.

“Is she Is she afraid? Yes, Amy said quietly.

But she’s brave.

It looks like she was trying to leave a record.

Valerie nodded, trembling.

She always liked to document things.

She carried notebooks everywhere.

Drew our dog 23 times in a row once, just because she wanted to remember how he looked when he slept.

She was documenting this, too.

Valerie’s voice broke.

Is there any way she might still be alive? Amy hesitated.

It’s possible.

We don’t have evidence of her death, only disappearance.

And the man, do you know who he is? We have a suspect.

His name is Caleb Taland.

Valerie stared.

Is he related to? Yes.

Abigail Taland.

Her brother Valerie backed up into the wall, shaking her head.

She taught my daughter.

11:03 p.

m.

Taland residence surveillance site.

Amy sat in an unmarked car across from the small bungalow on Hollowell Street.

Miss Abigail Taland hadn’t left the house all day.

Inside, the lights in her study were still on.

Amy had reviewed her alibi for the thousandth time.

Abigail claimed she hadn’t seen her brother in over 20 years, that he vanished after the incident, that she assumed he had died.

But someone had helped seal that chamber.

Someone with access to the school blueprints, someone with keys, and someone who had a reason to protect him.

And Abigail had all three.

The plan was already in motion.

A judge had approved a full property search.

Officers were prepping tools and protective gear.

In the meantime, Amy stared at the photo of Meline, clutching that folded card in the dim pink lit room.

Something about it nawed at her.

The card.

It wasn’t just a scrap.

It looked placed, folded, left with intent.

She leaned closer to the photo, magnifying it again.

The words on the front, just barely legible in the high-res scan, read for daddy.

November 17th, 2023.

Location: Wood Hollow, Minnesota, 9:06 a.

m.

Willow Pines.

assisted living Martin Kellerman hadn’t slept much since turning over the film.

The photo of Meline, the final frame haunted him, not because of the image itself, but because of what he didn’t remember, what he should have seen, what he may have buried to survive.

Detective Amy Salvon arrived with two cups of coffee and a quiet knock.

“You’re up early,” Martin said, his voice with age.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she replied.

He gestured to the chair across from his recliner.

That makes two of us.

She set the coffee down.

I need to ask about October 5th again.

Martin nodded slowly.

It’s all I think about lately.

Let’s start from what you do remember.

You were setting up.

You were alone.

Yes.

Do you remember Meline? Martin hesitated.

Only the photo, not her in person.

I’ve stared at that image so many times, but I can’t see the real child behind it.

Just the way her eyes looked, like she was about to say something or scream.

Amy gently placed a printed still on the table.

Frame 24, zoomed in.

Look at her shoulder, she said.

He leaned forward, squinting.

The hand.

Is it familiar? He swallowed.

The burns.

I remember those.

You saw them? Not that day.

Earlier, I think before Amy’s pulse quickened.

Before years ago, late ‘8s, maybe.

There was a man.

Used to show up outside my shoots.

Not close enough to worry anyone.

Just watching.

I assumed he was someone’s father at first, but then he showed up again.

Different school, same burned hand.

Did you report it? I didn’t think I needed to.

He never approached the kids, just stood at the edge of the gym or by the door.

No interaction.

I told a principal once, but they said he was probably harmless.

Amy leaned forward.

What did he look like? Thin, tall, greasy, dark hair.

Always wore a windbreaker, even in summer.

Left hand was always covered in gauze or gloves.

But the one time I saw it bare, the skin looked melted.

She pulled out a photo from the Taland family archives.

An old DMV license photo of Caleb Russell Taland, age 42.

Martin stared at it a long time.

I think that’s him.

11:45 a.

m.

Wood Hollow Police Department interview room.

Miss Abigail Taland sat with her hands clasped tightly, her purse untouched on the table.

She had been brought in again, this time under suspicion of obstruction, possibly accessory.

After the fact, Amy entered slowly.

No folder this time, no papers, just the photo.

She laid it down between them.

Madeline, the pink lit room, the folded card in her lap that read for daddy.

Abigail stared.

You knew, Amy said quietly.

Talin said nothing.

You knew what he’d done before.

You knew what he was capable of.

And you still vouched for him.

Still brought him back into that building.

I thought he’d changed.

Talin whispered.

He promised me.

Why didn’t you tell us about the room? I didn’t know about the room, but you saw him that day.

Talin looked up sharply.

Her eyes were wet but fierce.

I saw him once by the gym door.

I told him to leave.

I said he couldn’t be here, that I could lose my job.

And he just smiled.

He said, “I already got what I came for.

” “Why didn’t you report that?” I was scared.

I was ashamed.

He was my brother.

I thought if I stayed quiet, it would go away.

Amy leaned in.

“She wasn’t just a student, Abigail.

She was your student.

She trusted you.

And you left her with a monster.

” Talin bowed her head.

Do you think I don’t know that? There was silence between them.

And then softly, Abigail said, “He used to take things when we were kids.

Animals, strays, hide them in the shed, call them his pets.

My parents thought it was a phase.

They didn’t know or they didn’t want to know.

” And Meline, she was the one he never returned.

3:03 p.

m.

Forensic archive storage.

Amy and her team reviewed additional boxes of recovered school records.

In one misfiled folder from 1993, they found a single page, not typed, but handwritten in looping childlike letters.

It was a letter addressed to Daddy, likely Meline’s.

It read, “Dear Daddy, I was good today.

I wore the dress you liked.

I didn’t cry.

I ate the snack and used the corner like you said.

Please take me to the store soon like you promised.

I miss mommy.

Can I see her soon? I will be better.

Love, princess.

The page was smudged, the bottom corner torn, but the message was clear.

Meline had believed, at least at some point, that her abductor was her father, that he had convinced her of it.

The level of manipulation, the depth of control, it was beyond anything they had anticipated.

“He brainwashed her,” Lexi said quietly.

“She didn’t even know she was kidnapped.

” Amy stared at the letter, her jaw clenched.

“We’re going to find her.

” 6:27 p.

m.

St.

Louis County, Minnesota.

Using Caleb Talin’s last known residence as a starting point, officers canvas the outskirts of St.

Louis County.

After three false leads and a misidentified trailer, they located a condemned hunting cabin deep in the forest, 20 m off-rid.

Inside, they found more than dust.

They found tapes, dozens of VHS cassettes labeled with childish handwriting.

Princess Room, volume 1, volume 2, volume 6, volume 24.

And behind the paneling of the rear wall, they found a second hidden room.

It was empty.

No furniture, no lights, just insulation and a mattress stained with age.

But in the corner, tucked beneath a pink blanket nearly identical to the one in the school chamber, was a single object, a photo.

Meline, still in her yellow dress, smiling this time.

But the smile was wrong.

distant, hollow.

Her eyes didn’t look at the camera.

They looked through it as if she saw what was waiting on the other side.

November 18th, 2023.

Location: Wood Hollow Community Center, formerly Wood Hollow Elementary.

7:12 a.

m.

Old Auditorium suble access beneath the weathered stage of the former elementary school.

A maintenance hatch groaned open for the first time in decades.

The hinges shrieked like something alive.

Amy Salvon crouched with a flashlight in her gloved hand, breathing in the stench of old wood, mold, and something fainter, something more metallic blood.

The tech behind her adjusted his respirator.

“This place wasn’t on any blueprint,” he muttered.

“We only found it because the ground penetrating radar caught a weird hollow under the stage.

” Amy didn’t respond.

She ducked lower, boots scraping the dustcoated floorboards, and descended into the crawl space.

It was barely tall enough to crouch in.

The air was thick.

Walls of crumbling concrete surrounded her on three sides.

In the narrow beam of her flashlight, a small shoe emerged from the shadows.

Child-sized black patent leather, the same kind Meline had been wearing when she vanished.

She picked it up carefully.

Inside the heel, a faded marker scribble read, “Maddie, 7:40 a.

m.

Scene secured.

” The crawl space was larger than it first appeared, a jagged, uneven cavity running beneath the back half of the auditorium stage.

Over the years, dirt had collapsed in places, tree roots punched through one corner, but it had been used.

a blanket, a rusted lantern, a cracked mirror mounted to a wooden beam with duct tape, and in the far wall, just where the foundation curved toward the boiler room, a loose section of bricks.

Amy called in the structural engineers.

3 hours later, they pulled it apart.

Behind the bricks, a hollow compartment.

Inside, a metal lunchbox, its clasp rusted shut.

And next to it, wrapped in an old dish towel, a bundle of cassette tapes labeled in the same handwriting from the St.

Louis County Cabin.

Princess Room, volume 9, volume 10, volume 11, crawl 104 p.

m.

, police department, evidence processing room.

The lunchbox took nearly 20 minutes to open.

Inside were layers of plastic bags, carefully sealed, almost ritualistic.

At the very center, a Polaroid photo, bent and slightly mold speckled.

Meline again, but this time she wasn’t in a room.

She was outside or somewhere made to look like outside, a painted wall of trees, artificial grass.

Her arms were outstretched, and behind her stood a man wearing a deer mask.

Amy stared at the image, her pulse drumming.

The figure’s hand rested on Meline’s shoulder.

The same burned hand.

The same scars.

But it was what Meline held in her hands that made Amy stop breathing.

A photograph of herself, her school portrait.

3:30 p.

m.

audio lab.

The tapes were degraded but salvageable.

Technicians cleaned the magnetic strips, re-calibrated old players, and began digital transfer.

The first 15 minutes of Princess Room volume 11 were silence.

Then a voice crackled through the static.

Meline, day three.

I think it’s day three.

Daddy said I’m almost ready.

I don’t want to wear the mask.

He gets mad when I say no.

Another pause.

Then a second voice.

Male horse low.

You have to tell the truth, baby girl.

You have to tell the tape what you did.

Silence.

Then Meline again.

I didn’t cry when you turned the lights off.

I didn’t scream when you left.

I was good.

I was good.

The tape whed.

Something clicked in the background.

Possibly a switch or a door.

Then music.

Soft piano.

A lullabi warped by age.

And one final line from the man.

Tomorrow we start the crawl.

5:16 p.

m.

Talin property search.

With a warrant in hand and grounds cleared by the judge, law enforcement returned to Abigail Talin’s home.

Not the interior this time, the shed out back.

It was locked with a rusted padlock and surrounded by ivy.

Amy pried it open with bolt cutters.

Inside was chaos.

Dustcovered crates, spiderweb tools, the smell of mildew, and old wood.

But beneath the floorboards, they found it.

Another compartment.

Within it, children’s clothing folded old report cards, a purple backpack labeled Meline H in faded Sharpie, and beneath it all, a large Manila envelope sealed with masking tape.

Inside, Meline’s birth certificate, a forged adoption form listing Caleb Taland as legal guardian, a passport application that was never submitted, a worn notebook titled Princess Protocol, Phase 2.

Amy flipped it open.

The first page was a schedule, daily affirmations, dress rehearsal, playhouse sessions, silent dinner, crawl simulation.

The second page listed potential escape plans, and how to counter condition.

Then a disturbing note scrolled in red ink.

She still remembers her mother.

Must begin sleep interruptions.

Remove all mirrors.

Reinforce false memory.

I am father.

6:59 p.

m.

Wood Hollow PD observation room.

Amy stood behind the one-way glass, watching Abigail Taland break.

She was shaking, her hands trembling as she stared down at the contents of the manila envelope.

I didn’t know about the crawl space, she kept saying.

I didn’t help with that.

He told me she’d gone.

He said he gave her to someone else.

Did you ever see her again? No, Abigail whispered.

Only once.

I looked out my classroom window and I saw her in the garden behind the school just standing there.

She looked at me, then she disappeared like a ghost.

Amy pressed the talk button.

She wasn’t a ghost.

She was a child buried alive in the walls of the place you taught in.

while you looked away.

Abigail broke down sobbing.

9:45 p.

m.

Amy’s apartment.

She couldn’t sleep.

Not after hearing that voice on the tape.

Not after seeing that crawl space or the mask.

Not after knowing that Meline had once been just feet away scratching help into a foam wall while teachers taught spelling and children played tag on the lawn above her.

Amy pulled out the school photo again, Meline’s final frame.

She looked into those eyes, wide, afraid, resolute.

They weren’t just asking for help.

They were telling her where to look.

November 19th, 2023.

Location: Wood Hollow Police Department, Cold Case Unit.

Detective Amy Salvon stood before a wall of names.

On one side of the war room were photographs, Meline, her teachers, the principal, Martin the photographer.

On the other side, post-it notes for every person who had ever been temporarily employed by Wood Hollow Elementary in the fall of 1993.

Substitute teachers, cafeteria temps, custodial contractors.

In the middle of that collage was a single name they hadn’t been able to verify.

Jay Halpern, substitute teacher.

October 5th, 1993.

His file had always been thin, a temporary hire through a staffing agency the school had only used for one semester.

His employment record had no follow-up, no tax history, no criminal checks.

He had signed in that day, barely legible.

He had signed out just before lunch.

No one had seen him leave.

No one remembered him in the classroom except for one child, a now grown man Amy had tracked down through the old 2B yearbook.

10:13 a.

m.

Interview with Daniel Meyers, former class 2B student.

Daniel was in his late 30s now, a quiet man who taught high school science and still carried the same nervous energy he had as a child.

I remember picture day, he said.

Not because of the pictures, but because something felt off.

How so? Amy asked.

The teacher, he said.

She wasn’t our normal one.

Miss Taland was there in the morning, but after recess, we had a man, tall, thin, dark clothes.

He didn’t talk much.

Kept staring at us like he was taking mental notes.

Do you remember his name? Daniel shook his head.

We just called him the sub, but he made me nervous.

He smelled like something burned, like melted plastic.

Amy blinked.

Did he interact with Meline? Daniel paused.

She was sitting alone near the cubbies.

He bent down and whispered something to her.

She didn’t answer.

But after that, she stopped talking.

Even when we played heads up, Seven Up, she just stared at the door.

Do you remember seeing her after that number? I remember someone calling her name during snack, but she didn’t answer.

Then the alarm went off later and the teachers looked panicked.

Amy’s heartbeat faster.

You’re sure this man was in the room that day? Yes, he was there, but he wasn’t in the class photo.

That was true.

They had a group shot from that day taken just before lunch, and the man known as Jay Halpern was nowhere in it.

12:27 p.

m.

Records room Lexi Duran called in from Minneapolis.

I tracked the name, she said.

Jay Halper never existed, but we did find a falsified ID used to apply for a substitute teaching license in 1993.

Fingerprints were smudged, but the photo matches a man arrested twice under different names.

Let me guess, Amy said.

Caleb Taland.

Close.

The alias on the ID was Jeremiah Halpern, but the DMV photo matches Randall Clay, an associate of Caleb’s from St.

Louis County, known for making fake documents.

Last seen in Duth in 2005.

You think Caleb used his friend’s identity to get into the school? Exactly.

The real Randall was serving time during 1993.

We pulled mug shots and facial recognition confirms.

The sub that day wasn’t Randall Clay.

It was Caleb in disguise.

Using his associates paperwork, Amy hung up and stared at the board.

They had been looking for the wrong man, or rather, the right man under the wrong name.

3:15 p.

m.

Search of Talin’s abandoned vehicle.

The team recovered a rusted pickup truck registered to Caleb under another alias, Gregory Baines.

It had been abandoned in a salvage lot 20 m outside town.

Inside they found remnants of fast food, a burned out dash, and tucked beneath the seat, a spiralbound notebook.

It was damp, warped, and stained with what might have been coffee or blood.

Most pages were unintelligible, but one stood out.

The sub doesn’t speak.

The sub listens.

The sub helps me keep them still.

The girl is too loud.

She remembers the smell of her mother.

I told her the truth that the world ended.

That only I remain.

That she is my seed.

My new beginning.

Another page further back.

They called it a game.

Crawl, hide, pretend to be someone else.

She plays, she learns, she obeys until she doesn’t.

Beneath it in shaky handwriting that looked like a child’s.

I am not your daughter.

I am Meline Marie Harper.

My mother is real.

I will not forget.

Amy closed the notebook.

Meline had fought back even in captivity, even in isolation.

She had never surrendered her identity.

6:45 p.

m.

Emergency court filing.

Amy gathered everything.

The forged documents, the audio tapes, the fingerprints and photos, the notebook.

It was enough.

She filed an emergency motion for a full search warrant of any property formerly owned, rented, or affiliated with either Caleb Taland or Randall Clay, including hunting cabins, warehouses, and off-thegrid shelters.

The judge signed it within the hour.

8:02 p.

m.

Final tape review, Princess Room, Volume 24.

It opened with darkness, then breathing, a soft voice.

Meline’s.

If someone finds this, please tell mommy I didn’t run away.

I waited.

I didn’t stop waiting.

A pause, then footsteps.

Daddy says we’re going to a new place.

That I have to learn the crawl again.

That I’ll forget more this time, but I won’t.

I wrote it on the wall.

I wrote my name.

A shuffle, a whisper.

They can’t erase me.

Then the tape ended.

Amy sat in silence for a long time.

It was the last tape they had, but not the last place.

November the 20th, 2023.

Location, Wood Hollow PD, abandoned daylight facility, Northern Minnesota, 7:02 a.

m.

Wood Hollow PD, Forensic Imaging Lab.

They had looked at frame 24 a dozen times from every angle, enhanced, enlarged, stabilized.

But this morning, Amy stared at it differently.

She noticed the light.

It wasn’t fluorescent, not the cold blue of a classroom bulb, not the warm yellow of a domestic lamp.

The source cast a greenish tint like filtered daylight through thick plastic, industrial skylight, maybe.

And near the lower right corner of the frame, just behind Meline’s elbow, was something missed before.

lettering, painted, faded, barely legible.

Amy zoomed in.

It read D-4/S South Observation.

The lab technician froze beside her.

That’s not from the school.

No, Amy said.

It’s from somewhere else.

9:13 a.

m.

State Records vault.

Duth.

Buried in the state’s old mental health facility archive.

Lexi uncovered blueprints of a short-lived behavioral study wing attached to a now defunct child development center.

The building was called the Daylight Institute.

Decommissioned in 1991, privately owned, privately funded, connected to a nonprofit run by, of all people, Randall Clay, Caleb’s former alias donor.

The South Wing included a small cluster of rooms labeled D-1 to D-6.

one of them, D-4, observation room.

The facility had been shut down after allegations of unethical child therapy techniques and unregulated experimentation.

Amy stared at the map.

The room was small, no windows, but it had a skylight.

“This is it,” she whispered.

“This is frame 24.

” 12:32 p.

m.

Northern Minnesota, perimeter of the daylight facility.

The building was a ruin, gutted by time, claimed by vines and forest, tucked deep in the woods, surrounded by rusted chainlink fencing and a locked gate.

They cut the lock.

The air smelled like mildew and rust.

Inside, paint peeled from the walls in long strips.

The floorboards creaked under every step.

Shattered glass crunched beneath their boots.

They passed room D1, then D2, then here, Amy said, pointing.

D4.

The door had been welded shut.

It took a crowbar and brute force to break the seal.

Inside, the temperature dropped.

The air felt preserved, like something had been sealed inside.

12:58 p.

m.

D4, observation room.

They entered slowly.

The room was exactly as in the photo.

The foam insulation, the painted mural of trees, faded but recognizable.

The skylight above now shattered, filtered in muted green light through moss and grime.

And on the far wall, just where Meline had sat in frame 24, a faint discoloration.

Amy knelt down.

Her gloved fingers traced the faded lines of writing scratched into the insulation.

My name is Meline.

I am real.

I am not yours.

I remember.

And beside it, carved deeper than the rest, almost angrily.

They took my voice, but not my name.

Lexi crouched next to her.

Jesus.

Amy rose to her feet.

This wasn’t just confinement.

It was eraser.

1:42 p.

m.

Daylight facility.

Underground storage.

A back stairwell led down into a mold choked storage area.

Water had collapsed half the floor, but something caught their attention.

A steel locker half buried under debris.

Inside it were three items.

A cassette player, a cracked Polaroid camera, a sealed envelope labeled to the man who finds her.

Amy opened it carefully.

Inside a letter written in jerky ink blotted script.

You found her, didn’t you? You saw what I built.

She is better now.

She is more mine than yours.

She lives in my design.

You’ll never erase me, even if you erase the walls.

Because I was the only one who saw her clearly, and she saw me back.

She took my picture, too.

Beneath it, a final line.

Frame 28 was mine.

3:55 p.

m.

Forensic photo reconstruction.

Back at the lab, they examined the film negatives again.

Frame 27 had been declared blank, but the film team tried one last scan using alternate wavelength analysis.

A faint ghostlike image emerged.

Frame 28.

Someone had forced the film forward in extra time, snapping one more image.

Even though the cartridge was nearly empty, the shot was angled low.

The camera had been turned around.

It showed a man’s face, pale, unshaven, eyes sunken, teeth bared in a twisted half smile.

He held the camera at arms length.

Behind him was Meline, barely visible, her eyes wide.

Amy stepped back from the monitor.

Lexi stared.

That’s not Caleb.

Amy’s stomach dropped.

“No,” she said.

“That’s someone else.

” “Then who?” But Amy already knew.

512 p.

m.

Martin Kellerman’s residence.

He was waiting on the porch when they arrived.

His hands were folded.

His camera, the original 1993 Polaroid, sat beside him in a case.

He looked up as Amy approached.

“You figured it out,” he said.

Frame 28, she replied.

I didn’t take it.

No, she said, “But you gave him the camera.

” Martin’s eyes were glassy.

I was supposed to photograph the students, but I saw him.

I saw the way he watched her.

I tried to say something, but I didn’t.

Why did you lie? Because I was scared.

And because he promised me the photos were all he wanted.

Amy pulled out the image.

Then why did he pose with her? After Martin went silent and then he whispered because she took it.

She turned the camera around.

She made him the evidence.

November 21st, 2023.

Location, Wood Hollow, Duluth, St.

Mary’s Hospital, 7:05 a.

m.

Wood Hollow PD.

Maline Harper had left more than a name on the wall.

She had left a map.

Amy had spent the night pouring over every scratched word found inside room D4.

The layout, the phrasing, the spacing.

It wasn’t random.

It formed something.

Not a letter, a direction.

Meline had etched her movements.

Under the pipes left of the mattress, crawl four hands.

Touch brick.

It wasn’t just memory.

It was survival.

Amy pinned the printed close-up of the wall to the board and drew lines between the phrases.

A crude map took shape.

Coordinates to where Meline had once gone, or maybe where she had been taken next.

9:17 a.

m.

Duth Public Works archive Lexi found it first.

an old city permit issued under the name Gregory Baines, one of Caleb’s known aliases for plumbing repairs on an abandoned transit building near the freight yard.

Date of permit, October 9th, 1993, 4 days after Meline’s disappearance.

It was never inspected.

No sign off, no followup.

Amy stared at the location.

Underground, she whispered.

Lexi nodded.

The old maintenance corridor beneath the yard used to house homeless transients in the 80s sealed off now and accessible.

Amy asked if you know the old codes.

Caleb did.

11:30 a.

m.

Duluth freight yard access hatch.

9 C.

Rust gave way with effort.

They descended carefully, flashlight slicing through damp air and rot.

The corridor smelled of mildew, rusted metal, and something bitter chemical.

The concrete floor sloped slightly.

Their boots echoed.

After 50 ft, they found it.

A side chamber, a metal door half rusted shut.

It took both women, Amy and Lexi, to force it open.

Inside was a small windowless room, mattress, toys, a mirror with its glass cracked and fogged.

walls covered in children’s drawings, stick figures holding hands under yellow suns and scribbled M initials in every corner.

There was a word on the ceiling painted in red crayon.

Remember, and beneath the mattress, something wrapped in cloth.

Amy unwrapped it, a diary.

The first page was simple, in a child’s shaky hand.

My name is Meline Marie Harper.

I am 8 years old.

Today is day four.

I am learning how not to cry.

2:12 p.

m.

St.

Mary’s Hospital, Duth.

The forensics team recovered partial blood traces from the mattress, a fragment of blonde hair and saliva on the edge of the pillow.

Enough for a profile.

DNA comparison confirmed what Amy suspected.

Meline had been here.

And recently, not in 1993, not decades ago, within the last 2 years.

Amy sat in stunned silence, the lab results in her lap.

2 years, she whispered.

Lexi looked at her.

That means she might still be alive.

5:22 p.

m.

Surveillance video.

Duth bus terminal.

Archived footage.

August 17th, 2021.

Lexi was the one to make the connection.

A missing person’s report from 2021.

a Jane Doe who had been seen wandering barefoot through the terminal at midnight, muttering about walls that moved and games you can’t stop playing.

She had been taken to St.

Mary’s for a psych evaluation.

No ID, no fingerprints in the system.

Age estimated at 30, silent, withdrawn, refused food unless it was in plastic containers.

Slept under the bed.

No family ever came forward.

After 72 hours, she slipped out of the hospital unnoticed.

“Gone.

” Lexi pulled up the surveillance frame and froze.

“Tell me that’s not her,” she whispered.

Amy stared.

“It was older, gaunt, hair darker, but the eyes were the same.

” “Meline, 7:34 p.

m.

St.

Mary’s Hospital psychiatric archive room.

Amy and Lexi pulled the full file.

Patient number 1121-J.

Date admitted August 17th, 2021.

Time 12:47 a.

m.

Discharge: August 19th, 3:12 a.

m.

Notable behavior: rocking, avoidance of eye contact, repeating phrases in past tense, obsessive drawing of closed doors.

Her name had been listed as M, written on the back of a napkin, she clutched.

just am.

But in the corner of one evaluation sheet, the psychologist had made a note.

Patient used term princess room when asked about childhood trauma, associated it with discomfort, punishment, and fear of light exposure.

Amy’s hand trembled.

She flipped to the next page, a sketch drawn by Meline.

It was a crawl space with a child inside and above it the words, “She saw me when I was invisible, but I saw her first.

” 8:55 p.

m.

Returned to Wood Hollow.

Amy sat in her car outside the police station, staring at the photo.

Meline, older, lost, still surviving.

She wasn’t buried under floorboards.

She wasn’t intombed in walls.

She was out there.

She had escaped, but she wasn’t free.

Not really.

And Amy knew in her bones that somewhere in that twisted maze-like history of false names, fake fathers, and hidden rooms, Caleb Taland was still alive.

November 22nd, 2023.

Location, Duth, Minnesota, Lake Superior Forest Reserve.

6:35 a.

m.

Duth PD cold case unit.

She was seen again last month, Lexi said.

Amy looked up from the diary.

Where? Cass County.

A woman matching Meline’s adult profile was spotted walking near a trail head north of Leech Lake.

Local ranger said she asked if the rooms were still there.

When he said no, she turned and walked back into the woods.

Any followup? Lexi nodded grimly.

He didn’t report it until this week.

said she looked too broken to talk to Amy grabbed her jacket.

We leave in 20.

9:02 a.

m.

Lake Superior Forest Reserve, Ranger Station 14.

The ranger, a man in his 50s named Jerry Hayes, met them near the old fire road.

“I knew something was off the second I saw her,” he said.

“She didn’t walk like someone hiking.

She walked like someone trying not to be followed.

” He took them to where he’d seen her, a fork in the trail where the brush grew thick and the trees swallowed light.

She asked about cabins, old places.

I told her everything was gone.

She looked at me and said he kept one, the last one.

Then she disappeared.

Amy pulled out a map.

Did she say a name? A place? She said the place with the red door.

That’s all.

Lex’s face drained.

What? Amy asked.

Lexi held up the diary from the crawl space.

Page 16.

The red door is last.

If I get there, I can leave, but only if the door stays shut behind me.

10:26 a.

m.

Remote forest cabin.

Unmarked trail approx.

7 mi north.

The cabin looked like it hadn’t been touched in decades.

Weatherbeaten, swallowed by moss.

A roof that sagged.

No electricity.

No path but the door.

The door was painted red and fresh.

Not chipped, not faded.

New.

Amy raised her weapon.

Duluth PD, she called.

No answer.

They pushed the door open.

10:28 a.

m.

Inside the red door, silence greeted them.

And dust.

It wasn’t a living space.

Not anymore.

It was a memory box.

Each room held relics.

A lunchbox, a child’s dress, a broken tape player, a photo of a smiling girl in a schoolyard.

On one wall was a mural, stick figures, a woman, a child, a tall man with no face.

Beneath it, she got out, but the game never ends.

A creek from upstairs.

Both women spun.

Footsteps, but not running.

Careful, intentional.

Amy ascended slowly, every step echoing like a heartbeat.

10:32 a.

m.

upstairs bedroom.

She was there on the floor, knees pulled to her chest, pale, too thin, face framed by long dark hair gone gray at the ends.

Her eyes were wide, not with fear, recognition.

Madeline, Amy said softly.

The woman blinked.

You remembered.

Tears welled in Amy’s eyes.

We’ve been looking for you.

I left the pictures.

I wrote on the walls.

I scratched under the pipes, but no one came.

We’re here now, Amy said.

Too late, she whispered.

“He’s not gone.

” Meline pointed to the corner of the room.

There, lying in a bed beneath rotted blankets, was a body shriveled, decomposed, a man, half his face missing.

The rest burned beyond recognition.

Lexi stepped forward, gagging.

“He’s dead,” she said.

That’s Caleb.

No, Meline said and turned to the mirror on the wall.

He’s there.

The reflection showed only Meline, but behind her, faint and flickering like a ghost was frame 28.

The man’s face, smiling.

11:10 a.

m.

Evacuation and medical response.

Meline was taken carefully from the cabin.

She didn’t fight, didn’t speak, just clutched something wrapped in cloth.

At the hospital, they opened it.

Inside was the original camera still working.

A single cartridge inside, unprocessed, frame 29, a final image, not of Meline, not of Caleb, but of a red door closed, and behind it, scratches, dozens of them.

Fingernails dragged through paint, letters forming one word again and again.

Enough.

7:47 p.

m.

St.

Mary’s Hospital secure wing.

Maline Harper was alive, broken, but breathing.

She would need years of care, decades of healing, but she was free.

And when Amy asked if she remembered her mother, Meline nodded slowly.

I remember her voice.

Do you want to see her? Meline looked out the window, then back to the detective.

If I see her, will I stop dreaming? Amy didn’t answer, but she stayed in the room long after the lights dimmed.

April 5th, 2024.

Location: Wood Hollow, Minnesota.

It was spring again.

The Dogwoods had bloomed in front of the newly renovated Wood Hollow Elementary, now transformed into the Wood Hollow Children’s Resource Center, a place dedicated to trauma recovery, early intervention, and safe education.

The air smelled of fresh paint, and tulips.

Sunlight poured in through open windows.

Where room 2B once stood, a new wing had risen, full of books, toys, and counselors who listened.

On the wall in the front hallway hung a black and white school portrait.

Frame 24.

Maline Harper.

Unedited, unccropped, preserved.

Beneath it, a plaque in honor of those who were lost and those who were found.

Too late.

We promised to look closer.

Duluth, Minnesota, St.

Mary’s Psychiatric Annex.

Meline didn’t speak often, but she was drawing again.

pages and pages.

Some with stick figures, others with hands pressed against walls, one with a little girl sitting in a chair surrounded by eyes drawn in crayon.

Sometimes she smiled briefly, softly.

The therapy team let her listen to music now, mostly lullabibis.

One day, she asked if they still took school pictures.

When the therapist said yes, Meline nodded.

I used to think they were traps.

She said, “Cameras like eyes that froze you.

” She tapped her drawing.

But sometimes they keep you alive.

Lexi Duran’s apartment, Minneapolis.

Lexi kept a copy of frame 28 tucked in her personal file, the one with the man’s face, and Meline blurred behind him.

She didn’t keep it out of obsession.

She kept it to remind herself that sometimes the truth hides in plain sight.

In corners of frames, in names scratched on walls, in children who don’t scream but still whisper.

She gave a lecture at the state university.

Now, how missing children vanish without moving.

Attendance was standing room only.

Detective Amy Salvon, field notes.

Final entry.

The first time I saw Meline, it was through a photograph.

The last time she was standing in a hospital hallway watching the wind move the trees.

I didn’t ask her for details.

I didn’t need to.

She survived.

Not because we were fast.

We weren’t.

Not because we were clever.

We weren’t always.

She survived because she remembered who she was when no one else did.

That’s not just survival.

That’s resistance.

Somewhere in the storage vault of the St.

Louis County Evidence Lab is a sealed envelope.

Inside is the original roll of undeveloped Polaroids.

They never developed frame 30.

They’re not sure they want to because if frame 29 was the door, frame 30 might show what was behind it.

And some truths should remain in the dark even when the light is finally turned on.

Subscribe for more true crime mystery stories based on real investigative methods and survivor accounts.

News

🐘 “Mamdani’s Nightmare Becomes Reality: Investigation Exposes the Untold Truth!” 💔 “In a dramatic twist, the investigation has unearthed everything Mamdani tried to conceal!” As the details emerge, Zohran Mamdani’s reputation hangs in the balance. What devastating information has been revealed, and how will it affect his standing in the political arena? 👇