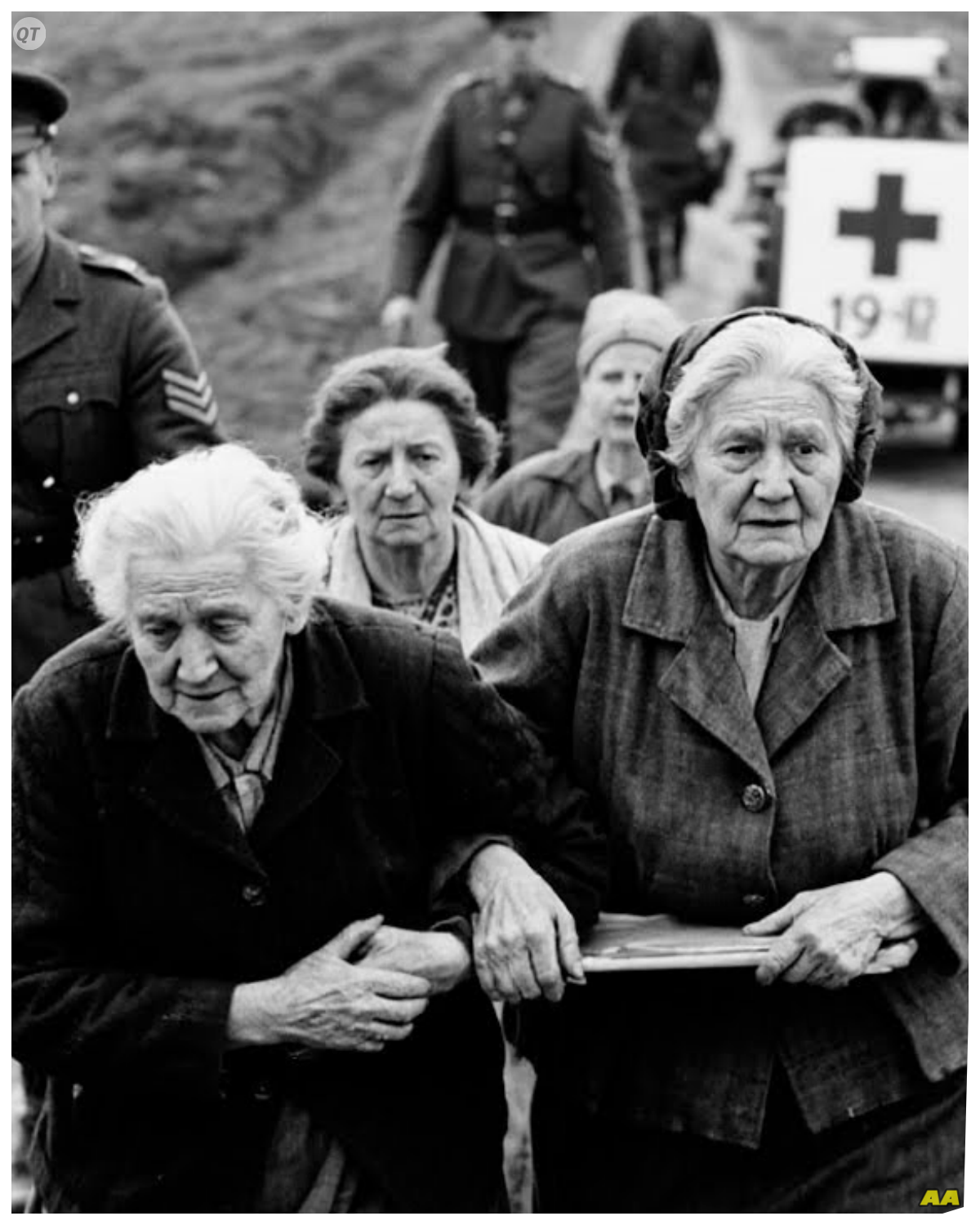

Bavaria, April 1945.

The road stretched through pine forest and morning mist.

12 mi of muddy track between a makeshift prisoner camp and the nearest field hospital with adequate supplies.

Three elderly German women lay on crude stretchers fashioned from blankets and tree branches, their breathing shallow, their bodies failing from pneumonia and exhaustion, and the accumulated weight of years spent surviving a war that had consumed their sons and grandsons.

The American medics who found them boys from Iowa and Tennessee who had fought across Europe faced a choice.

leave these enemy civilians to die as their own forces had abandoned them or carry them through mountain terrain to care they desperately needed.

What they chose and why would challenge everything both sides had been taught about enemies and worth and the obligations.

Humans owed to other humans even across the deepest divides of war.

Corporal James Sullivan had been a medic for 2 years, had treated wounds across France and Belgium and Germany, had seen enough suffering that he thought himself hardened against shock.

But finding the three old women in the abandoned camp still made him stop and stare.

His training momentarily suspended by the sheer roundness of what lay before him.

The camp was unofficial, just a clearing in Bavarian forest, were retreating.

German forces had hurried civilians they couldn’t or would untake further.

A few crude shelters made from branches and salvaged materials.

Evidence of recent occupation fire pits with cold ashes, belongings scattered where people had dropped them in desperate flight.

And three women, elderly and sick, left behind when everyone else had fled or been evacuated.

Sullivan’s unit, a medical detachment attached to the 45th Infantry Division, had been following advancing.

American lines treating wounded and processing prisoners and civilians caught in the collapse.

They had stumbled on the camp by accident, taking a forest road that seemed passable when the main route was choked with refugees and military traffic.

Sergeant Marcus Washington, the detachment senior NCO, knelt beside the first woman.

She was maybe 70, gray hair matted with dirt and sweat, her breathing labored and wet sounding.

Pneumonia, Washington assessed with the quick competence of someone who had diagnosed hundreds of cases.

Advanced, untreated, in a body already weakened by malnutrition and stress.

The second woman was in similar condition, younger, perhaps 65, but her color was wrong.

skin taking on the grayish tint that meant organs were beginning to fail.

The third woman was conscious, barely, her eyes tracking Washington’s movements with fear and confusion.

Private Danny Chun, the unit srtlatter child of Chinese immigrants who had learned German in college before the war spoke to the conscious woman in careful German.

Who are you? Where are the others? How long have you been here? The woman’s response came in fragments.

She was Fra Bergman.

The other two were Fra Keller and Fra Schmidt.

They were grandmothers.

All three from a village 30 km away.

German forces retreating ahead of American advance had taken civilians with them.

The young and healthy at gunpoint.

The old and sick left behind because they slowed movement and consumed resources that were needed for soldiers.

They had been here 3 days, maybe four.

Time had become uncertain, measured only by the progression of sickness and the intervals when Fra Bergman had managed to give the other two water from a nearby stream.

No food remained, no medicine, no shelter beyond the crude lean tubes that provided minimal protection from April Mountain cold.

We were told Americans would come.

Fra Bergman whispered in German that Chun translated.

We were told you would help, or at least you would not.

She couldn’t finish the sentence, but the meaning was clear.

They had been left to die, abandoned by their own people, told that enemy forces might show mercy or might not.

But either way, they were no longer German militar’s responsibility.

Sullivan looked at Washington.

The sergeant’s expression was carefully neutral, but Sullivan could read the calculation happening behind his eyes.

These were enemy civilians.

Not combatants, not prisoners of war, exactly, but Germans who had presumably supported the regime, but American forces had been fighting for years.

Military doctrine said to process them, send them to displaced persons camps, let others handle civilian complications.

But doctrine assumed civilians could walk, could move under their own power, could survive the journey to proper facilities.

These women couldn’t walk, would die within days, maybe hours, without medical intervention.

The nearest aid station was 12 mi back the way Sullivan’s unit had come.

12 mi of mountain road that would be difficult even for healthy soldiers, nearly impossible for patients in critical condition.

Washington stood, brushed dirt from his knees, and looked at his unit.

Five medics plus himself.

They had supplies for treating combat wounds, bandages, sulfa drugs, morphine, but not for sustained care of critical pneumonia patients.

They had a jeep, but the road beyond this point was impassible for vehicles, blocked by fallen trees and shell craters from recent fighting.

Lieutenant Morrison, the detachment’s commander, had stayed with the jeep a half mile back where the road deteriorated.

Sullivan volunteered to retrieve him.

Joged back through forest that still smelled of cordite and disturbed earth.

Found Morrison checking maps and trying to determine the best route forward.

Sir, we’ve got a situation.

Sullivan began and explained what they had found.

Morrison listened without interrupting, his face showing the same calculation Washington had displayed.

He was 24 years old, had been promoted to lieutenant 6 months earlier after his predecessor was killed in Belgium, and carried the weight of command decisions that required choosing between competing moral obligations.

Their civilians? Morrison asked.

Yes, sir.

Elderly.

German forces left them behind.

Combat age Germans, potential combatants, grandmothers, sir.

70s, maybe 60s, sick with pneumonia.

He’ll die without treatment.

Morrison was quiet for a long moment.

Then can they be moved? With stretchers and time, yes, sir, but it’s 12 mi to our forward aid station.

Rough terrain.

We’d need to carry them the whole way.

The lieutenant looked at his map at the road ahead that was supposed to be their assigned route at the practical reality that following assigned routes while leading dying civilians behind created one kind of moral burden while deviating from orders to save enemies created different complications.

“Show me,” Morrison said.

Finally, they walked back to the clearing.

Morrison examined the three women with clinical detachment, then spoke quietly with Washington about what moving them would require.

Stretchers would need to be improvised from available materials.

The women would need to be stabilized as much as possible before transport basic treatment for pneumonia, fluids if they could take them, morphine for pain.

The journey would take most of a day, maybe longer, carrying patients through terrain that was challenging even without burden.

“This will take us off our assigned route,” Morrison said, stating the obvious.

“Our orders are to support forward advancement, not to provide care for enemy civilians.

” “Yes, sir,” Washington acknowledged.

“Command isn’t going to like this.

” “No, sir.

” Morrison looked at the three women at Fra Bergman, who was watching the Americans with fear and desperate hope at Fra, Keller, and Fra Schmidt, who were barely conscious and might not survive transport, regardless of how careful the medics were.

But we can’t just leave them.

Morrison said, “Not quite a question.

” “No, sir,” Washington agreed.

“We can’t,” the lieutenant nodded.

decision made even though it violated efficient military logic and would require explanations to superiors who valued following orders over humanitarian gestures toward enemy populations.

All right, make stretchers.

Stabilize them as much as you can.

We move out in an hour.

Radio command that we’re deviating from route due to civilian emergency medical situation.

They’ll be angry, but they can be angry after we’ve done what needs doing.

Private Tommy Walsh, had been a carpenter before the war, had learned woodworking from his father in small, Iowa town, where everyone knew everyone, and helped neighbors build barns and repair houses.

Now he used those skills to fashion stretchers from pine branches and salvage canvas.

Lashing together frames that would be strong enough to carry adult weight across rough terrain without collapsing.

He worked methodically cutting branches to proper lengths with a folding saw from his pack, binding them with paracord in patterns his father had taught him, creating frames that were crude but functional.

Chun helped following Walsh’s instructions, learning improvised engineering that wasn’t part of medical training, but was essential for survival in situations doctrine had an anticipated.

Sullivan focused on the patients.

Fra Keller was the most critical.

Her fever was dangerously high, her breathing rapid and shallow, her consciousness minimal.

He gave her sulfa drugs crushed and dissolved in water, hoping her body could absorb enough to slow infections progression.

He covered her with blankets from medical supplies, trying to maintain warmth without overheating already fevered flesh.

Fra Schmidt was slightly better, conscious enough to take water and medicine without choking.

She watched Sullivan with eyes that showed confusion and fear.

Unable to understand why American soldiers were helping rather than harming or simply leaving, Sullivan worked without speaking, his hands gentle despite the urgency, treating her with the same care he would apply to American casualties.

Fra Bergman was alert enough to talk, and Chun sat with her while waiting for stretchers to be completed.

He explained in German what the Americans planned to carry them to a field hospital where proper treatment was available where pneumonia could be addressed by doctors with antibiotics and equipment beyond what medics carried in packs.

Why? Fra Bergman asked genuinely confused.

We are Germans.

You are Americans.

Why would you help? Chun struggled to answer in German adequate for the philosophical question.

Because you’re sick, he said finally.

Because we can help.

Because leaving you to die would be wrong.

But we are enemies.

Your grandmothers who have been left to die by your own forces.

That makes you victims, not enemies.

Fragman began to cry, not from pain, but from the sudden emotional overload of unexpected mercy after abandonment by her own people.

The regime’s forces had left them without food or medicine or shelter, had treated elderly civilians as disposable burdens, and now enemy soldiers were fashioning stretchers, planning an arduous journey, providing medical care that German military had denied.

“My grandson,” she said between Saabs.

“My grandson is a soldier somewhere in the east.

We think we haven’t heard from him in months.

He might be dot dot dot.

” she couldn’t finish.

“Might be dead, might be captured, might be fighting still in the war’s final desperate days.

” “I hope he’s safe,” Jon said quietly.

“I hope that if he needs help, someone shows him the mercy we’re showing you.

” The stretchers were completed by midday.

Walsh had built them solid, designed to be carried by two men with poles resting on shoulders.

The patient secured in canvas slings that distributed weight evenly.

Not comfortable, but functional and as safe as improvised medical transport could be.

Washington organized the team.

Morrison and Sullivan would carry Fra Keller, the most critical patient.

Washington and Walsh would carry Fra Schmidt.

Shawn and Private Rodriguez would carry Fra Birdman.

They would rotate positions every hour, switching between carrying and walking unbburdened, sharing the physical burden so no one exhausted themselves too quickly.

The plan was simple.

Follow the road back to where the jeep waited, then continue on passable track to the forward aid station 12 mi distant.

Take breaks every hour.

Monitor patients constantly.

If any woman’s condition deteriorated critically, administer morphine and make her comfortable, but keep moving because stopping in the forest wouldn’t save anyone.

Morrison radioed command.

We have civilian medical emergency.

Three elderly German females requiring immediate evacuation.

We are deviating from assigned route to transport patients to forward aid station.

Baker, estimate arrival, 18800 hours.

Request approval and medical preparation for pneumonia patients.

Their response crackled back.

Negative on route deviation.

Your orders are to advance forward.

Civilian casualties are secondary priority.

Do not deviate from mission.

Morrison looked at his men at the three sick women on stretchers at the choice between following orders and doing what his conscience said was necessary.

Then he keyed the radio again.

Respectfully, we cannot leave critical patients to die.

We are proceeding with evacuation.

Morrison out.

He turned off the radio before command could respond further.

The men stared at him, understanding that their lieutenant had justified direct orders, had chosen humanitarian obligation over military discipline, had risked his career, and possibly court marshal for three elderly German women he had never met before this morning.

Let’s move, Morrison said quietly.

We’re burning daylight.

The first hour was the hardest because muscles weren’t yet warmed, and the weight of stretchers felt impossible.

Sullivan and Morrison carried Fra Keller, their shoulders aching from poles that seemed to grow heavier with each step.

The unconscious woman breathd weightely, each inhalation a struggle, her fever burning through blankets that tried to maintain warmth.

The forest path was uneven roots and rocks and mud from recent rain that made footing treacherous.

Sullivan concentrated on each step, on placing his boots carefully, on maintaining rhythm with Morrison, so the stretcher stayed level and didn’t jostle the patient unnecessarily.

Behind them, Washington and Walsh carried Fra Schmidt, then Chung and Rodriguez with Fra Bergman.

They walked in silence except for breathing and the occasional muttered warning about obstacles ahead.

The morning was cool, mountain air carrying sense of pine and damp earth, but exertion brought sweat despite temperature.

Sullivan felt moisture running down his back, his uniform growing damp beneath his medical pack, his shoulders screaming protest against poles that dug into tissue and bone.

At the hour mark, Morrison called halt.

They set down stretchers gently, rotated positions.

Sullivan moving to help with FA Schmidt.

Walsh taking Morrison’s place with Fra Keller.

Chun checked patients conditions while others drank water and tried to give their shoulders brief relief.

Fra Keller’s breathing was worse.

Shallower, more labored, her collar taking on grayish tint that meant oxygen wasn’t reaching tissues adequately.

Sullivan administered more sulfa drugs, adjusted her blankets, checked her pulse, and found it racing and weak.

She might not survive the journey, might not survive another hour, but leaving her would guarantee death, while carrying her at least provided chance.

They resumed.

Sullivan now walked unburdened for an hour.

His job to scout ahead to find the easiest path through terrain.

It grew progressively rougher.

He called back warnings about deep mud or fallen logs, tried to identify roots that would minimize carrying difficulty.

The second hour was worse than the first because muscles were tiring and the initial determination was giving way to grinding physical reality.

Morrison carried Fra Schmidt, now partnered with Rodriguez, feeling the weight in his shoulders and lower back, fighting the urge to suggest they rest longer than scheduled because rest meant delay, and delay might mean death for patients who are barely clinging to survival.

Walsh carried Fra Bergman with Washington, listening to the conscious woman whisper prayers in German he didn’t understand.

She was praying for her grandson.

Shan translated later, praying that God would protect him and bring him home safely.

Praying that this war would end before it consume everyone.

Praying that the Americans carrying her would be rewarded for mercy shown to someone who had nothing to offer in return except gratitude and prayer.

At the 2-hour mark, they reached the jeep.

Morrison tried the radio again, despite knowing command would be angry about his disobedience.

The response was predictable.

Lieutenant Morrison, who are ordered to cease civilian evacuation and return to assigned route immediately.

This is a direct order from Colonel Henderson, acknowledged.

Morrison acknowledged, then explained that patients would die if abandoned, that evacuation was humanitarian necessity, that he would accept full responsibility and face whatever consequences command deemed appropriate after patients were delivered to medical care.

The radio went silent.

Either command was formulating response or had given up trying to order back a lieutenant who was clearly going to do what he thought was right regardless of military discipline.

They continued, “The road was better here passable for vehicles, relatively flat, less treacherous underfoot, but the distance remained daunting, and the patients were deteriorating.

Fra Keller’s fever spiked higher.

Fra Schmidt became unresponsive.

Even Fra Bergman’s consciousness wavered, exhaustion and sickness overwhelming her despite the Americans efforts to keep her stable.

The third hour brought them halfway.

6 mi covered, 6 mi remaining, and every man’s shoulders were raw beneath poles that had rubbed skin away through fabric.

Sullivan rotated back to carrying Fra Keller with Chun.

Felt the woman sight and the terrible responsibility of keeping her level and moving and alive through terrain that wanted to destroy all three of them.

His shoulders screamed.

His back cramped.

His legs trembled with fatigue.

But he kept walking because stopping meant failure.

meant watching an old woman die in forest because he wasn’t strong enough to carry her the distance she needed to survive.

The other men felt the same walls gritting his teeth against pain.

Washington maintaining steady pace despite obvious exhaustion.

Rodriguez singing quietly under his breath to maintain rhythm.

Morrison led though he could barely stand straight.

His shoulders were bleeding beneath his jacket, the skin torn from pole friction.

His back spasomezed with each step, but he was the officer, and if he stopped, the men would stop, and stopping meant death for women who had already been abandoned once and deserved better than to be abandoned again by soldiers who had promised help.

At the fourth hour, Shan called for emergency halt.

Fra Keller had stopped breathing.

Sullivan dropped his end of the stretcher and ran to the patient’s head, checking airways, finding them clear.

but no respirations occurring.

He tilted her head back, pinched her nose, and breathd into her mouth one, two, three, four breaths, forcing air into lungs that had forgotten how to pull it in themselves.

Washington took over chest compressions, pressing on Fra Keller’s sternum with steady rhythm, trying to force heart to beat when it wanted to stop.

Sullivan continued rescue breathing.

Count and breathe.

Count and breathe.

while the other men stood watching, helpless, knowing that losing one patient here would make the entire journey pointless.

1 minute, 2 minutes.

Washington’s arms burning with effort, Sullivan’s lungs aching from forced breathing.

3 minutes, 4.

Fra Keller remained still, her body refusing to restart, her system too depleted to respond to intervention.

In a gasp, weak, barely present, but a gasp.

Her chest moved independently, drawing shallow breath.

Her heart stuttered back into irregular rhythm.

Not healthy, not stable, but alive, breathing, surviving for at least another moment.

They gave her morphine, knowing it would suppress respiration further, but also knowing that pain and stress were killing her as surely as pneumonia.

Then they lifted stretchers and resumed moving faster now because time was running out because Fro Keller might code again and next time resuscitation might fail.

The fifth hour was pure will.

Sullivan’s shoulders were past pain, had moved into numbness that worried him because numbness meant tissue damage.

He could feel blood soaking his undershirt where skin had torn.

Could feel his legs shaking with each step.

Could feel his body approaching its limits and threatening collapse.

But Fre Keller was breathing.

That mattered more than personal discomfort.

She was breathing because he and Shun were carrying her.

Because Washington had restarted her heart.

Because Morrison had defied orders to make this possible.

She was alive.

and alive meant there was still chance for full recovery if they reached medical care in time.

The sixth hour brought them within sight of forward aid station Baker.

Tents and vehicles clustered around a fair mouse that had been converted to field hospital.

Smoke rising from medical incinerators.

The organized chaos of military medicine visible even from distance.

Morrison radioed ahead.

Three critical civilian patients, advanced pneumonia, require immediate intensive care.

Adah, 15 minutes.

The response came from the aid station’s commanding physician.

We’re ready for them.

Bring them straight to the main tent.

The final mile was the longest.

Sullivan’s vision narrowed, his focus reducing to just the path ahead and the pole on his shoulder, and the woman whose life depended on him maintaining strength for 15 more minutes.

His legs moved automatically, muscle memory overriding conscious thought, training and determination, carrying him forward when body wanted to quit.

They reached the aid station as sun touched western horizon.

12 m completed in 8 hours.

Three elderly German women delivered alive to medical care that might save them.

Doctors and nurses swarmed the stretchers, assessing patients rapidly, calling for antibiotics and oxygen and four fluids, working with practice deficiency to stabilize women who had been dying in forest 12 hours earlier.

Morrison collapsed against a tent pole, his shoulders seizing and cramps that made him cry out despite attempts to maintain officer dignity.

Sullivan sat on the ground, unable to stand, feeling his body shake with exhaustion and delayed stress.

Washington pulled off his jacket and found his shoulders bleeding, fabric stuck to torn skin.

The evidence of what carrying humans for 12 mi had cost.

The commanding physician, Major Hawkins, gay-haired and competent, examined the arrivals, then sought out Morrison.

Who authorized this evacuation? he asked, not hostile, but genuinely curious.

I did, Morrison replied.

Against orders.

Command wanted us to leave them.

Hawkins nodded slowly.

Their own forces abandoned them.

Yes, sir.

Left them to die in a forest with no food, no medicine, no help.

And you decided that wasn’t acceptable.

It wasn’t acceptable, sir.

They’re human beings.

Sick, elderly, helpless human beings.

We had the capability to help.

Leaving them would have been.

He struggled for words.

Would have made us no better than the forces that abandoned them.

Hawkins smiled slightly.

You’re going to face consequences.

Colonel Henderson is furious about the deviation from assigned route.

But you did the right thing.

These women would have died without intervention.

Now they have fighting chance.

He paused.

Off the record, I’d have done the same thing.

On the record, I have to report that you defied direct orders to aid enemy civilians, and command will have to decide what that merits.

I understand, sir.

The major returned to his patience, leaving Morrison and his men to contemplate what they had done and what it might cost them.

Fra Keller survived.

Not easily, not quickly, but she survived.

The antibiotics available at the aid station penicellin just starting to be widely distributed to Ford medical units attacked the pneumonia that had nearly taken her life.

Oxygen therapy helped her damaged lungs recover function.

IV fluids rehydrated tissue that had been depleting for days.

Within 48 hours, her fever broke and within a week she was conscious and able to speak.

Fra Schmidt recovered faster.

her case less advanced, her body responding quickly to treatment.

Within 3 days, she was sitting up, eating solid food, asking Shun to translate questions to the American medical staff, who had saved her life.

Fra Bergman needed the least intensive care, but took the longest to recover emotionally.

She kept asking why the Americans had helped.

Couldn’t reconcile enemy soldiers carrying her 12 mi with the propaganda that it promised.

American forces would show no mercy to German civilians.

Chun sat with her, explained through translation, and gradually she began to understand that ideology and reality were different things, that humans could choose mercy even toward enemies, that the Americans who had carried her were ant monsters, but young men who had seen suffering and decided they could have had to it by abandoning helpless women.

Morrison faced court marshall charges, not formal trial, but administrative discipline for disobeying direct orders during combat operations.

He was called to headquarters, required to explain his decisions to officers who valued military discipline and following command structure regardless of humanitarian considerations.

Colonel Henderson was blunt in his assessment.

Lieutenant, you violated direct orders.

You took your unit off assigned route, potentially compromising operational security to aid enemy civilians.

This is unacceptable in subordination.

Morrison stood at attention, accepted the criticism, and offered no defense except truth.

Sir, I believe that leaving three dying women in the forest was morally wrong.

I accept full responsibility for my decision and any consequences you deem appropriate.

Henderson studied him for a long moment.

If I had been in your position, Lieutenant, I probably would have made the same choice.

But I’m not in your position.

I’m in command position, which means I have to maintain discipline and ensure orders are followed.

You’re officially reprimanded for insubordination.

This will go in your record, but unofficially between us.

You did something decent in a war that hasn’t had enough decent moments.

dismissed and men faced no official consequences.

But the story spread through the division.

How an American medical detachment had spent eight hours carrying elderly.

German women through mountain terrain had defied orders to provide care to enemies, had chosen humanity over efficiency.

Some soldiers thought it was foolish sentimentality.

Others saw it as evidence that Americans could maintain moral standards even during total war.

Two weeks later, Fu Keller was well enough to be transferred to a displaced person’s camp where German civilians were being processed.

Before leaving, she asked Thu Chun to meet the men who had saved her life.

Morrison, Sullivan, Washington, Walsh, Chun, and Rodriguez stood in the hospital tent while the three elderly women thanked them in German that did require translation to convey meaning.

Fra Keller spoke for all three.

You carried us when your own people would not.

You showed mercy when we deserved only justice for what our nation did.

We cannot repay what you have given us.

We have nothing to offer except our gratitude and our prayers that God will bless you for your kindness.

We will remember.

We will tell our families if we find them that American soldiers saved our lives when German soldiers abandoned us.

We will tell the truth about what happened here so that people understand war does not eliminate all decency, that enemies can choose mercy, that humanity persists even in the darkest times.

Sullivan felt tears on his face and didn’t bother wiping them away.

Washington nodded, unable to speak.

Morrison managed a response in German he had learned from Chun.

We did what was right.

That’s all.

The women were transferred the next day.

Morrison’s unit resumed normal duties, treating combat casualties and processing prisoners, and moving forward as German resistance collapsed entirely.

The war ended 3 weeks later, and the men returned to civilian lives, carrying memories of firefights and friends lost, and the particular weight of stretchers bearing elderly women through 12 miles of Bavarian forest.

40 years later in 1985, James Sullivan received a letter from Germany.

It came through channels that had tracked him down through veterans organizations and military records.

Had followed connections across four decades to find the medic who had helped carry an elderly German woman to safety.

The letter was from Fra Keller’s granddaughter.

Her grandmother had survived the war, had returned to her village, had lived another 30 years before passing peacefully in her bed, surrounded by family.

Before her death, she had told her story countless times, about being abandoned by German forces, about American soldiers who had defied orders to save enemy civilians, about being carried through mountains by young men who had shown mercy when mercy was not required or expected.

My grandmother never forgot, the granddaughter wrote in careful English.

She taught us that hatred is a choice, that enemies can become saviors, that the Americans who won the war also showed humanity in their victory.

She wanted you to know that your kindness affected not just her, but all of us her children and grandchildren who exist because you chose to carry an old woman instead of leaving her to die.

We owe you our existence and we wanted you to know that your mercy multiplied across generations.

Sullivan sat in his Iowa living room, the letter in hands that were now old themselves, and cried for the woman he had, helped carry for the war that had required such choices for the unexpected.

Grace of knowing that his decision to help an enemy had rippled forward through decades and touched lives he would never meet.

He wrote back told Fra Keller’s granddaughter that he had only done what seemed right, that the real heroes were the women who had survived.

Despite abandonment that he hoped Germany had rebuilt into something better than the regime that had caused such suffering, the correspondence continued for years.

letters crossing the Atlantic building connection between families that had once been enemies but were united by one moment of mercy in a Bavarian forest.

Marcus Washington kept the photograph.

Someone had taken it at the aid station Morrison and his men standing with the three German women they had saved.

All of them exhausted but alive.

Washington had it framed, hung it in his home in Tennessee.

And when grandchildren asked about the war, he told them this story.

Not about battles or victory, but about carrying elderly enemies to safety, about choosing humanity over hatred, about the truth that real strength is measured in mercy shown to those who cannot reciprocate.

Thomas Morrison’s official record showed the reprimand for insubordination alongside his service.

Medals and commendations.

When he applied for post-war jobs, some employers asked about the reprimand.

Morrison always explained honestly he had disobeyed orders to save dying women and he would make the same choice again.

Most employers respected that.

The ones who didn’t work people he wanted to work for anyway.

The story became part of division lore, told and retold, sometimes exaggerated in ways that made the journey longer or the danger greater or the women esratitude more dramatic.

But the core remained true.

In April 1945, six American medics had carried three elderly German women 12 miles through mountain terrain, had defied orders and risked their careers, had chosen mercy toward enemies who had been abandoned by their own people.

Later historians would note the incident as representative of how American forces approached occupation not with systematic vengeance but with attempts to maintain humanity despite legitimate anger about the regime’s crimes.

The story appeared in books about postwar reconstruction in studies of military medical ethics in examinations of how moral choices are made under extreme conditions.

But for the men who had lived it, the story was simpler.

They had found three dying women.

They had the capability to help.

They had carried them to safety.

Everything else the orders defied.

The consequences faced.

The decades of remembrance flowed from that basic choice to see enemies as humans worthy of mercy.

Sullivan kept a photograph too different from Washington’s.

In his Fra Keller was conscious, smiling weakly from her hospital bed, her hand reaching toward the camera in gesture of thanks.

Sullivan looked at that photograph when the world seemed cruel.

When news showed humans treating each other with hatred and violence, when he needed reminder that mercy was possible even between enemies, that humanity could persist even during war.

A choice they had made to carry rather than abandon, to help rather than leave, to choose mercy over efficiency, hadn’t won any battles or changed strategic outcomes.

But it had saved three lives.

Had rippled forward through generations.

Had demonstrated that even in war’s darkest moments, humans could choose decency over hatred, compassion over convenience, humanity over the systematic dehumanization that war encouraged.

12 m through Bavarian forest, eight hours of carrying.

Three elderly German women delivered alive to medical care.

It was a small moment in an enormous war barely noteworthy in the grand scope of history.

But it mattered to those women, to their families, to the men who had made the choice to help.

And to everyone who would hear the story and understand that mercy given to enemies who cannot reciprocate is perhaps the truest measure of human worth.

News

German General Evaded Arrest in the Final Days — 79 Years Later, His Remote Alpine Refuge Was Found

In the final chaotic hours of World War II, as Allied forces closed in from all sides and the Third…

🐘 Nike’s Shocking Choice: Alex Eala’s $45 Million Contract Leaves Sabalenka in the Shadows! 🌪️ “One moment in the spotlight can change everything!” In an unexpected twist, Nike has announced a groundbreaking $45 million contract for tennis prodigy Alex Eala, effectively sidelining Aryna Sabalenka. As the tennis world buzzes with speculation, the implications for both athletes are immense. Can Sabalenka reclaim her position, or will this snub redefine her career? The drama unfolds as the competition heats up! 👇

The Shocking Snub: Nike’s $45 Million Contract for Alex Eala Leaves Aryna Sabalenka Reeling In a dramatic turn of events…

🐘 Revenge Motive Explored: Forensic Expert Raises Alarming Questions in Guthrie Case! ⚡ “The past has a way of catching up with us, especially in matters of revenge!” A renowned forensic expert has put forth a chilling theory that revenge may be a key motive in the ongoing investigation of Nancy Guthrie’s case. As the implications of this theory unfold, the community is left to ponder the relationships and rivalries that could have led to such a drastic act. Will this insight lead to the breakthrough everyone has been waiting for, or will it deepen the mystery? 👇

The Dark Motive: Revenge Uncovered in the Nancy Guthrie Case In a shocking revelation that feels like the climax of…

🐘 Emergency Alert: Boeing’s Departure from Chicago Sends Illinois Into a Frenzy! 💣 “Sometimes, the sky isn’t the limit—it’s the beginning of a downfall!” In an unprecedented move, Boeing has announced it will shut down its Chicago operations, leaving the Illinois governor scrambling to manage the fallout. As uncertainty looms over thousands of jobs and the local economy, the political ramifications are vast. Can the governor stabilize the situation, or is this just the beginning of a much larger crisis? The clock is ticking! 👇

The Boeing Exodus: Illinois Governor Faces Crisis as Jobs Fly Away In a shocking turn of events that has sent…

🐘 Nancy Guthrie Case Takes a Dramatic Turn: New Range Rover Evidence Discovered! 🌪️ “Sometimes, the truth rides in style!” In a shocking turn of events, authorities have unearthed new evidence related to a Range Rover that could change everything in the Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, questions abound: what does this mean for the timeline of events? With emotions running high and the community demanding answers, the stakes have never been greater. Will this lead to a breakthrough, or is it just another twist in a long and winding road? 👇

The Shocking Revelation: New Evidence in the Nancy Guthrie Case Changes Everything In a gripping twist that feels ripped from…

🐘 Lawmakers Erupt: Mamdani’s Deceitful Campaign Promises Under Fire! 💣 “Trust is the currency of politics, and Mamdani is bankrupt!” In a dramatic clash, lawmakers have slammed Mamdani for betraying the trust of New Yorkers with his hollow promises. As the investigation unfolds, the community is left in shock—what does this mean for the future of leadership in the city? With public confidence at an all-time low, the pressure is on Mamdani to make amends or face the consequences of his actions. The clock is ticking! 👇

The Reckoning: Zohran Mamdani’s Broken Promises and the Fallout In the heart of New York City, a storm is brewing…

End of content

No more pages to load