In the final chaotic hours of World War II, as Allied forces closed in from all sides and the Third Reich crumbled into ash and rubble, one highranking German general simply vanished.

No surrender, no capture, no body ever found.

For nearly eight decades, his disappearance remained one of history’s most enduring mysteries.

Then in 2024, a team of Alpine researchers stumbled upon something extraordinary hidden deep in the Austrian mountains.

What they discovered would not only solve a 79-year-old puzzle, but reveal a story of survival so incredible that it defied everything historians thought they knew about the war’s final days.

April 30th, 1,945.

Berlin was burning.

Soviet artillery pounded the city into submission while Hitler retreated to his underground bunker for the last time.

Across the collapsing German Empire, military commanders faced an impossible choice.

Surrender and face war crimes tribunals, flee and spend their lives as fugitives, or fight to the bitter end and likely die in the rubble of their fallen nation.

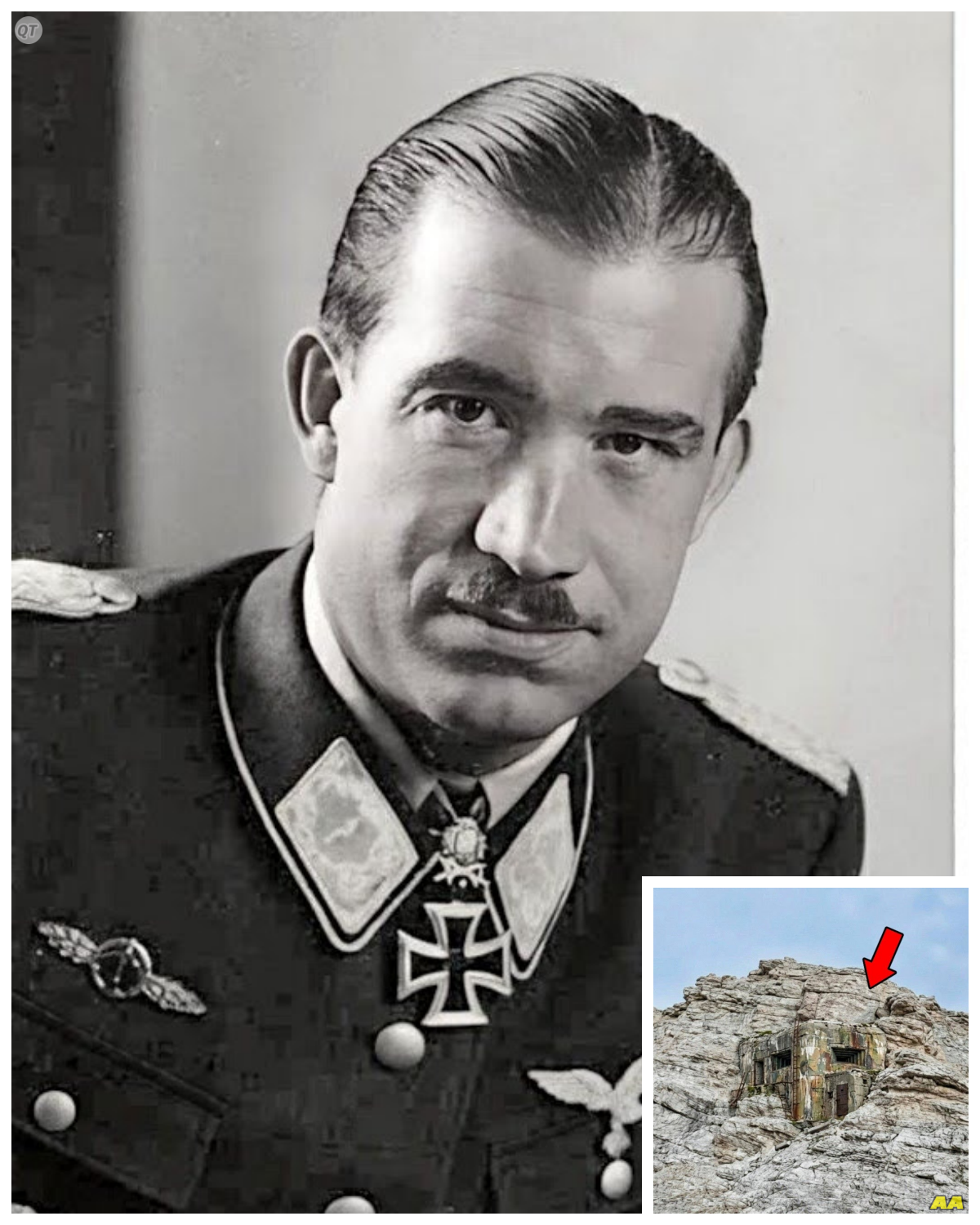

General Hinrich von Waldberg chose none of these options.

Instead, he disappeared completely.

Von Waldahberg wasn’t just any vermached officer.

As commander of the 14th Alpine Division, he had earned a reputation as one of Germany’s most capable mountain warfare specialists.

His troops had fought across Norway’s frozen fjords, the peaks of the Caucasus, and the treacherous passes of the Italian Alps.

But more importantly, von Waldahberg possessed something that made him extremely valuable to the Allies and extremely dangerous as a fugitive.

He knew the locations of every secret alpine fortress, every hidden weapons cache, and every escape route the Nazi leadership had prepared for their final retreat into the mountains.

The last confirmed sighting of General von Waldahberg came from his aid to camp, Lieutenant Klaus Weber, who survived the war and spent decades being questioned by Allied intelligence services.

Weber’s testimony painted a picture of a man who seemed to know something the rest of the German high command didn’t.

3 days before Berlin fell, von Valdberg had dismissed his entire staff, destroyed his personal files, and loaded a single military truck with supplies.

When We Weber asked where the general was going, Von Waldberg simply replied that he had preparations to make for a very long winter.

That truck was found abandoned two weeks later on a mountain road near Insbrook, Austria.

Inside were Von Waldahberg’s uniform, his iron cross, and a handwritten note that read, “The war is over, but the mountains are eternal.

” No trace of the general himself was ever discovered.

Allied intelligence agencies launched one of the most intensive manhunts in post-war history.

Operation Alpine Search involved hundreds of investigators, mountain climbing specialists, and local informants combing through every village, every cave, and every abandoned building across the Austrian and Swiss Alps.

They questioned shepherds, checked monastery records, and followed up on thousands of reported sightings that led nowhere.

The search continued for three full years before being quietly abandoned in 1948.

Some investigators believed van Waldahberg had successfully escaped to South America, joining other Nazi fugitives in Argentina or Paraguay.

Others suspected he had been killed by resistance fighters or had died attempting to cross into neutral Switzerland.

A few persistent rumors suggested he had assumed a false identity and was living quietly somewhere in the mountains.

But these stories were never substantiated.

Dr.

Sarah Mitchell, a military historian at Oxford University, who has spent 15 years studying Nazi escape routes, explains the challenge investigators faced.

Von Wahberg was uniquely qualified to disappear in the Alps.

He had spent his entire military career in mountain environments and possessed an intimate knowledge of terrain that would be impossible for outsiders to navigate.

If anyone could vanish completely in those peaks, it would be someone with his expertise and resources.

The mystery deepened when in 1952 a cache of gold coins bearing Nazi insignia was discovered by hikers in a remote Austrian valley.

The coins were traced to reserves that van Wahlberg’s division had been responsible for protecting in the war’s final weeks.

This discovery reignited interest in the case, but despite renewed searching efforts, no additional clues emerged.

Over the decades, the story of the vanishing general became the stuff of legend.

Local mountain guides told tourists about the ghost of von Waldahberg supposedly still wandering the high peaks in his Vermach uniform.

Adventure writers penned novels about his escape.

Documentary filmmakers produced speculative programs exploring various theories about his fate.

But gradually, as the war generation passed away and new conflicts captured public attention, the mystery of Heinrich von Valdberg faded into historical footnote.

That changed on September 23rd, 2024 when Dr.

Elena Kohler and her team from the Austrian Alpine Research Institute made a discovery that would rewrite everything we thought we knew about the missing general.

Dr.

caller’s team wasn’t looking for Nazi fugitives.

They were conducting a routine survey of glacial retreat in the high Austrian Alps, documenting how climate change was exposing previously hidden areas of the mountains using ground penetrating radar and thermal imaging equipment.

They were mapping newly exposed terrain when their instruments detected something unusual at an elevation of nearly 11,000 ft.

Hidden beneath decades of accumulated snow and ice, the radar revealed what appeared to be artificial structures.

The readings showed geometric patterns that clearly weren’t natural rock formations.

At first, the team assumed they had discovered some kind of old mining operation or perhaps abandoned military installations from World War I.

But as they began carefully excavating the site, they realized they had found something far more extraordinary.

The structures weren’t random buildings, but rather an elaborate complex that had been deliberately concealed and engineered for long-term survival in one of the most hostile environments on Earth.

Stone walls were reinforced with steel beams.

Multiple chambers were connected by carefully constructed tunnels.

Most remarkably, the entire facility showed evidence of sophisticated ventilation systems and what appeared to be geothermal heating.

As the excavation continued, Dr.

Kohler’s team began finding personal artifacts that would change everything.

Military equipment bearing Vermach markings, maps of Alpine roots marked in German, personal items that included a leatherbound journal filled with entries dated from 1,945 through 1,963.

The journal’s first entry, written in precise German script, read, “The Reich has fallen, but I remain.

These mountains will be my final command post.

” It was signed with the initials HV.

When German military historians examined the handwriting, they confirmed what the research team had begun to suspect.

The journal belonged to General Heinrich vonvaldberg.

After 79 years, they had found his hiding place.

But the discovery raised more questions than it answered.

The journal entries revealed that von Wahberg hadn’t simply hidden in the mountains and died.

He had constructed an elaborate survival compound and lived there for nearly two decades, emerging only occasionally to gather supplies and monitor the changing world below.

The entries describe a man who had methodically prepared for his disappearance long before the war ended.

Von Waldahberg had apparently been secretly transporting supplies and construction materials to this remote location for months, possibly years.

He had studied alpine survival techniques, established hidden supply caches, and even recruited a small network of local sympathizers who helped maintain his refuge without knowing his true identity.

The compound itself was a masterpiece of mountain engineering.

Von Waldahberg had chosen a location that was virtually impossible to reach except by expert climbers familiar with the specific route.

The site was protected from avalanches by natural rock overhangs and hidden from aerial observation by careful camouflage.

Solar collectors disguised as rock formations provided electricity.

A natural spring supplied fresh water.

Food storage areas were carved directly into the mountain stone heart.

Most remarkably, the facility included a sophisticated communication center.

Von Wahberg had apparently maintained contact with the outside world throughout his exile, monitoring Allied intelligence activities and tracking the fates of other Nazi fugitives.

Radio equipment found in the compound was far more advanced than anything typically available to military units in 1945, suggesting he had access to resources and technology that remained classified decades after the war ended.

Dr.

Kohler’s team also discovered extensive documentation that von Waldahberg had kept detailed records of post-war developments.

He tracked the Nuremberg trials, the formation of NATO, the beginning of the Cold War, and the establishment of both East and West Germany.

His journals show he remained convinced that a new conflict between the Soviet Union and Western powers was inevitable, and he apparently saw himself as preparing for a role in that future war.

The psychological profile that emerges from these records is that of a man who refused to accept that his cause was lost.

Fonwaldberg wrote extensively about his belief that national socialist ideology would eventually resurface in some form.

He developed elaborate plans for rebuilding military organizations and maintained lists of former Vermacht officers he hoped to recruit for future operations.

But perhaps the most chilling discovery in von Waldahberg’s mountain fortress was evidence that he hadn’t been alone.

Personal belongings found throughout the complex suggested that at least three other individuals had lived in the compound for extended periods.

Clothing in different sizes, multiple sets of dining utensils, and sleeping quarters designed for several occupants painted a picture of a small community hidden in the peaks.

Among these belongings, investigators found items that would send shock waves through the historical community.

Documents bearing the names and photographs of war criminals who had supposedly died or disappeared in the war’s aftermath.

Men like SS Oberfurer Carl Brener, who had vanished while fleeing Yugoslavia in 1945, and Sternbun furer Otto Kesler, who was believed to have drowned crossing the Danube.

Von Waldahberg’s journals revealed that both men had made their way to the Alpine Refuge and lived there for years.

The compound had served as more than just a hiding place.

It was a headquarters for a network of Nazi fugitives who refused to surrender.

Von Waldahberg’s meticulous records detailed a system of safe houses, forged documents, and financial resources that had helped dozens of war criminals escape justice.

Swiss bank account numbers were carefully cataloged alongside the true identities and assumed names of men who had committed some of the war’s worst atrocities.

Dr.

Mitchell explains the significance of this discovery.

For decades, intelligence agencies had suspected that escaping Nazis had maintained some form of organized network, but proof had always remained elusive.

Von Waldahberg’s archives provided the first concrete evidence of how extensively these fugitives had coordinated their escapes and continued operations.

The journal entries from the 1,950 seconds reveal a man growing increasingly paranoid and isolated.

Von Waldberg wrote about nightmares where Allied forces discovered his location.

He described elaborate security measures, including early warning systems using mirrors to reflect sunlight and coded messages left at predetermined locations throughout the mountains.

Anyone approaching the compound had to know specific signals or risk triggering defensive measures that von Waldahberg had installed around the perimeter.

By 1958, the tone of the entries had shifted dramatically.

Von Wahlberg’s companions had begun leaving the compound, some to attempt new lives under false identities, others to join established Nazi communities in South America.

The general found himself increasingly alone, his grand plans for a fourth Reich, fading into the reality of a changing world that had moved beyond the conflicts that had defined his life.

The final journal entries dated 1,963 reveal a broken man struggling with the weight of his isolation.

Von Waldahberg wrote about his failing health, his inability to maintain the complex systems that had kept him alive for so long, and his growing realization that he would die forgotten in the mountains he had chosen as his sanctuary.

The last entry written in increasingly shaky handwriting simply states, “The mountains have claimed their final victory.

I go to join my fallen comrades.

” But von Waldahberg’s story doesn’t end with his death.

Dr.

Kohler’s team discovered evidence that the compound had been visited repeatedly over the decades following the general’s death.

Supplies had been replenished, equipment maintained, and new additions constructed.

Someone or perhaps several people had been preserving Fonwaldberg’s mountain fortress long after his passing.

Security cameras hidden throughout the site had captured grainy footage of figures moving through the complex as recently as 2019.

The individuals wore modern clothing and carried contemporary equipment, but their faces remained hidden beneath hoods and masks.

They appeared to know the compound’s layout intimately, moving with the confidence of people who had been there many times before.

Among the more recent additions to the compound, investigators found modern communication equipment, updated maps of European political boundaries, and disturbing evidence of ongoing activities.

Computer hard drives contained encrypted files that digital forensics experts are still attempting to decode.

Preliminary analysis suggests the drives contain databases of personal information, financial records, and what appears to be surveillance data on individuals across multiple countries.

The discovery has prompted urgent meetings between intelligence agencies across Europe.

If von Waldahberg’s compound has continued operating as a hub for extremist activities, the implications extend far beyond historical curiosity.

The site may have served as a training ground, meeting place, and coordination center for individuals and organizations committed to reviving Nazi ideology in the modern world.

Local authorities in Austria have established a security perimeter around the site, while international investigators work to uncover the full scope of what they’ve discovered.

The compound’s remote location and sophisticated concealment methods suggests that whoever has been maintaining it possesses significant resources and expertise.

The fact that it remained hidden for nearly eight decades indicates a level of operational security that concerns counterterrorism specialists.

DNA evidence collected from the site has been submitted for analysis against international databases of known extremists and suspected war criminals.

Early results have already produced several matches to individuals previously thought to be dead or whose whereabouts were unknown.

The revelation that some of these people may have been alive and active decades longer than previously believed is forcing historians and intelligence agencies to reconsider everything they thought they knew about postwar Nazi networks.

The compound’s extensive library provides another window into the mindset of its inhabitants.

Thousands of books, pamphlets, and documents span subjects from military strategy to racial theory to detailed studies of modern democratic governments.

Many volumes contain handwritten annotations in multiple languages, suggesting that von Waldberg and his associates had been conducting serious research into contemporary political systems and potential vulnerabilities.

Of particular concern to investigators are detailed floor plans and security assessments of government buildings, military installations, and civilian infrastructure across Europe.

These documents appear to have been compiled over decades with regular updates reflecting changes in security procedures and defensive capabilities.

The level of detail suggests access to classified information that should have been impossible for private individuals to obtain.

Among the most disturbing discoveries are training manuals that outline techniques for infiltrating modern security systems, conducting surveillance operations, and executing coordinated attacks on multiple targets simultaneously.

These documents show clear evidence of evolution over time, incorporating lessons learned from various terrorist incidents and adapting to changing technology and security measures.

The psychological profiles found in von Waldahberg’s personal files reveal a sophisticated understanding of recruitment and radicalization techniques.

Detailed assessments of potential recruits include analysis of their psychological vulnerabilities, family backgrounds, and ideological predispositions.

The profiles suggest that whoever continued von Waldahberg’s work had developed highly effective methods for identifying and cultivating individuals susceptible to extremist indoctrination.

Financial records discovered in the compound trace, a complex network of funding sources that spans multiple countries and decades.

Shell companies, numbered accounts, and cryptocurrency wallets point to an organization with substantial resources and international reach.

The money trail connects to legitimate businesses, charitable organizations, and political movements across Europe and beyond, suggesting a level of infiltration that intelligence agencies are only beginning to understand.

Perhaps most troubling of all, the compound contained detailed plans for future operations.

Maps marked with potential targets, timets for coordinated activities, and contingency plans for various scenarios paint a picture of an organization that views its work as far from finished.

The scope and ambition of these plans suggest that Von Waldahberg’s mountain refuge may have served as the headquarters for activities that pose ongoing threats to democratic societies across Europe.

As investigators continue their work, each new discovery raises more questions about how extensive this network may be and how many similar facilities might exist in remote locations across the Alpine region.

The sophistication of vonvalberg’s operation suggests that other high-ranking Nazi officials may have established their own hidden strongholds, creating a web of connected safe houses and operational centers that remained active long after the war’s official end.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond historical interest.

If vonvaldberg’s compound represents just one node in a larger network of hidden Nazi infrastructure, the security challenges facing modern Europe may be far more complex than previously imagined.

complex than previously imagined.

The Austrian government has classified much of what investigators found in von Waldahberg’s compound, but leaked documents reveal connections that stretch across continents.

Banking records show regular transfers to accounts in Argentina, Paraguay, and Chile, the same South American countries where Nazi hunters had long suspected war criminals had fled.

But these weren’t payments to fugitives living in exile.

They were operational funds flowing back to Europe, financing activities that investigators are still trying to fully comprehend.

Dr.

Dr.

Hans Mueller, a specialist in post-war Nazi networks at the University of Vienna, has spent months analyzing the financial data.

The patterns he’s discovered suggest von Waldahberg’s organization operated more like a modern multinational corporation than a traditional extremist group.

Investments in legitimate businesses provided cover for money laundering.

Charitable foundations created pathways for moving funds without scrutiny.

Political donations bought influence and access in ways that remained invisible to traditional oversight mechanisms.

The timeline revealed in von Waldberg’s archives shows how methodically he had planned his disappearance and subsequent operations.

As early as 1,943, when it became clear that Germany was losing the war, he had begun establishing the infrastructure for his mountain retreat.

supply runs disguised as routine military operations had stockpiled everything from construction materials to decades worth of preserved food.

Local contractors hired through intermediaries and told they were building weather stations or research facilities had unknowingly helped construct what would become one of history’s most sophisticated hideouts.

But von Wahlberg’s genius lay not just in concealment, but in adaptation.

As the decades passed and the world changed around him, he had continuously updated his methods and objectives.

The Cold War presented new opportunities, and his journals reveal attempts to position himself as a potential asset to Western intelligence agencies fighting Soviet influence.

He had prepared detailed assessments of communist infiltration in European governments and offered his services to anyone willing to overlook his past in exchange for his expertise.

These overtures were apparently rejected, but they demonstrate von Wahberg’s understanding that survival required more than just hiding.

He needed to remain relevant to find new purposes that would justify the resources his network consumed.

By the 1,962 seconds, his focus had shifted toward what he called ideological preservation.

The compound became less a military headquarters and more a library and training center dedicated to maintaining Nazi doctrine for future generations.

The educational materials found in the compound reveal a curriculum designed to indoctrinate young people who had no direct experience of World War II.

Simplified histories portrayed Nazi Germany as a misunderstood movement betrayed by international conspiracies.

Complex philosophical arguments attempted to justify racial theories using pseudocientific language that sounded academic but promoted the same deadly ideologies that had led to the Holocaust.

Most disturbing were the recruitment records that showed how this indoctrination system had been put into practice.

Starting in the 1,972 seconds, the compound had hosted summer camps for teenagers whose parents believed they were attending alpine adventure programs.

These young people, selected from families with known extremist sympathies, underwent weeks of intensive programming disguised as outdoor education and character building.

Former participants in these programs, now elderly themselves, have begun coming forward as news of the compound’s discovery spread.

Their testimonies paint a picture of sophisticated psychological manipulation that combined legitimate wilderness training with gradual exposure to Nazi ideology.

Many described feeling honored to be selected for what they were told were exclusive leadership development programs.

Only later did they realize they had been systematically radicalized.

Maria Hoffman, now 67, attended one of these camps in 1974 when she was 16.

She remembers being told she was part of a special group chosen to preserve European culture and traditions.

The camp counselors, who she now realizes were likely former SS officers, taught survival skills during the day and European history at night.

The history lessons gradually became more focused on racial theory and the supposed threats facing white Europeans from immigration and multiculturalism.

These camps continued for over three decades, creating networks of individuals who shared common experiences and ideological foundations even as they returned to normal lives across Europe.

Many participants went on to careers in government, law enforcement, education, and business.

carrying with them the beliefs and connections formed during their time in vonvberg’s mountain retreat.

The compound’s communication center had maintained contact with many of these former participants throughout their adult lives.

Encrypted messages provided ideological reinforcement, career guidance, and coordination for activities that advanced the network’s objectives.

A successful businessman might receive suggestions about which political candidates to support financially.

A teacher might get curriculum recommendations that subtly promoted certain historical interpretations.

A police officer might be encouraged to focus investigations in ways that served the organization’s interests.

This system of distributed influence had operated for decades without detection because it avoided the obvious mistakes that had exposed other extremist networks.

There were no mass rallies, no public demonstrations, no violent attacks that would attract law enforcement attention.

Instead, the network worked through quiet influence, gradual persuasion, and patient long-term planning that prioritized ideological victory over immediate action.

The digital evidence found in the compound’s computers reveals how this approach had evolved with changing technology.

Social media platforms provided new opportunities for spreading propaganda to wider audiences.

Online forums allowed for recruitment and coordination without geographic limitations.

Cryptocurrency enabled financial transactions that were nearly impossible for traditional law enforcement to trace.

By 2020, according to the most recent files recovered from the site, the network had established active cells in over a dozen European countries.

Each cell operated independently, following general guidance from the Alpine headquarters, but adapting tactics to local conditions.

The cells focused on infiltrating existing political movements, educational institutions, and community organizations rather than creating obvious extremist groups that would attract scrutiny.

The sophistication of these operations becomes clear when examining specific case studies documented in von Waldahberg’s files.

In one instance, the network had identified a small rural community struggling with economic decline and immigration concerns.

Over several years, they had moved sympathetic families into the area, supported local political candidates who shared their views, and gradually shifted the community’s entire political culture without most residents realizing what was happening.

Similar operations had been conducted in urban areas targeting universities, labor unions, and professional associations.

The network’s approach was always the same.

Identify existing tensions and grievances, then provide solutions that gradually moved target populations toward accepting extremist ideologies as reasonable responses to legitimate concerns.

The medical facilities found in the compound raise additional disturbing questions about the network’s activities.

Sophisticated surgical equipment, blood storage capabilities, and pharmaceutical supplies suggest operations that went far beyond treating routine injuries or illnesses.

Genetic testing equipment found alongside extensive genealogical databases implies research into racial characteristics that echoes the pseudocientific programs of Nazi Germany.

DNA samples stored in the compounds laboratory freezers have been traced to individuals across Europe, many of whom have no idea their genetic material was ever collected.

The sampling appears to have been conducted through seemingly legitimate medical research programs, ancestry testing services, and health screening initiatives that were actually fronts for the network’s research activities.

The purpose of this genetic research remains unclear, but documents reference plans for biological verification of racial theories and genetic mapping of European populations.

Computer models found in the compound attempted to trace bloodlines and identify individuals who met certain genetic criteria, though the scientific validity of these analyses is highly questionable.

Perhaps most chilling are references to genetic intervention programs that suggest the network had been exploring ways to influence human reproduction to achieve their ideological objectives.

Fertility clinics, adoption agencies, and sperm banks mentioned in their files are now under investigation to determine whether they were used to implement eugenic policies disguised as legitimate medical services.

The network’s interest in genetic research connects to broader patterns of infiltration in academic and scientific institutions.

Universities across Europe are discovering that research programs they believed were studying population genetics, evolutionary biology, or medical anthropology were actually being used to provide academic credibility for racial theories that most scientists had discredited decades earlier.

The compound’s archives contain correspondence with professors, researchers, and academic administrators who may not have realized they were supporting extremist research objectives.

Legitimate scientific questions about human genetics and population differences were being manipulated to support conclusions that advanced the network’s ideological agenda.

Dr.

Elizabeth Weber, a geneticist at the Max Plank Institute, who discovered her research had been cited in several of the compounds documents, expressed horror at how her work on European genetic diversity had been misrepresented.

Her studies of migration patterns and genetic markers were being used to support claims about racial superiority that completely contradicted her actual findings and conclusions.

The revelation that respected academic research had been co-opted by von Wahberg’s network has prompted urgent reviews of research funding, publication standards, and collaboration protocols at institutions across Europe.

Universities are discovering that what they believed were legitimate research partnerships may have been elaborate schemes to provide academic cover for extremist activities.

The scope of this academic infiltration appears to extend beyond genetics into fields like archaeology, anthropology, history, and political science.

Research programs examining European cultural heritage, ancient civilizations, and traditional societies were being used to develop narratives that portrayed certain ethnic groups as inherently superior to others.

These academic connections provided the network with something even more valuable than research data, credibility, and respectability that allowed their ideas to spread into mainstream discourse without being recognized as extremist propaganda.

Policy papers citing seemingly legitimate research influenced government decisions about immigration, education, and social services in ways that advanced the network’s long-term objectives.

The compound’s influence on European politics becomes clearer when examining voting patterns, policy changes, and political appointments in regions where the network had established active operations.

Statistical analysis reveals correlations between network activity and shifts in public opinion that suggests their influence campaigns had been remarkably effective.

In several cases, politicians who received financial support from network connected donors went on to implement policies that directly benefited the organization’s objectives.

Immigration restrictions, education reforms, and law enforcement priorities all showed signs of being shaped by the network’s strategic influence rather than genuine democratic processes.

The network’s political operations had been particularly focused on local and regional governments where individual votes carried more weight and public scrutiny was less intense.

By building influence at these levels, they could affect national politics through accumulated pressure from below while avoiding the attention that direct involvement in high-profile campaigns might attract.

As investigators continue analyzing the vast archive of documents found in von Waldahberg’s compound, each revelation raises new questions about how deeply this network had penetrated European society and how many similar operations might still be active.

The discovery has fundamentally changed how security agencies view the ongoing threat from Nazi ideology and forced a complete reassessment of counterterrorism priorities across the continent.

The mountain retreat that Hinrich von Waldberg built as his final refuge had become something far more dangerous than anyone imagined.

the headquarters for a shadow organization that had spent decades quietly reshaping European politics, society, and culture according to principles that most people believed had died with the Third Reich.

The investigation into von Waldahberg’s network has revealed connections that reach into the highest levels of European society.

Banking executives, media moguls, and government officials whose names appear in the compound’s files are now facing intense scrutiny from intelligence agencies across multiple countries.

Many of these individuals claimed they had no knowledge of the network’s true nature, insisting they believed they were supporting legitimate cultural preservation societies or historical research foundations.

But the evidence suggests otherwise.

Detailed psychological profiles found in von Waldahberg’s personal files show that recruitment had been extraordinarily selective.

The network didn’t randomly approach wealthy or influential people.

Instead, they conducted extensive background research to identify individuals whose personal histories, family connections, or ideological leanings made them susceptible to their particular brand of persuasion.

Take the case of Marcus Hoffman, a prominent Swiss banker whose grandfather had served in the Vermacht during World War II.

According to documents found in the compound, the network had spent two years studying Hoffman’s family history, political donations, and personal associations before making contact.

They approached him not as extremists, but as historians working to rehabilitate the reputation of ordinary German soldiers who had been unfairly demonized after the war.

Hoffman’s initial involvement was limited to providing modest financial support for what he believed were academic research projects, but the network gradually deepened his commitment through a process they called ideological evolution.

Each new request was slightly more significant than the last.

Each new revelation about their true objectives was presented as a natural extension of beliefs he had already accepted.

By the time Hoffman realized he was funding activities that went far beyond historical research, he had become too deeply implicated to withdraw safely.

The network possessed detailed records of every transaction, every meeting, every statement of support he had provided.

Attempting to expose them would have destroyed his career and possibly resulted in criminal charges for his own participation in their activities.

This pattern of gradual enttrapment appears throughout the network’s recruitment files.

They had perfected techniques for identifying and exploiting the psychological vulnerabilities that made successful people willing to compromise their principles.

Guilt about family histories during the war, resentment about Germany’s post-war treatment, fears about immigration and cultural change, ambition for political influence, all became tools for manipulation in the hands of vonvalberg’s successors.

The network’s media operations had been equally sophisticated.

Rather than creating obvious propaganda outlets that would be dismissed as extremist publications, they had infiltrated existing media organizations and established seemingly independent news sources that gradually shifted public discourse in directions that served their objectives.

Journalists whose work appeared in major European newspapers and magazines were receiving story suggestions, source recommendations, and research assistants from network operatives posing as academic consultants or policy experts.

Many of these journalists had no idea they were being manipulated, believing they were simply receiving help from knowledgeable sources who shared their professional interests.

The compound’s archives contain detailed analyses of media coverage patterns across Europe, tracking how successfully their influence operations had shaped public opinion on key issues.

Immigration stories that emphasized cultural conflict over economic benefits, historical articles that rehabilitated Nazi era figures, political coverage that promoted candidates sympathetic to their views, all showed clear signs of network coordination.

Perhaps most disturbing was evidence that the network had been actively working to discredit Holocaust education and remembrance programs.

Rather than engaging in obvious denial that would be immediately recognized and rejected, they promoted subtle revisionism that gradually undermined public understanding of Nazi crimes without appearing to challenge established historical facts.

Educational materials found in the compound included lesson plans designed to be introduced into school curricula across Europe.

These materials didn’t deny the Holocaust, but they systematically minimized its significance while emphasizing German suffering during and after the war.

Jewish victimhood was acknowledged, but placed in contexts that suggested it was part of broader patterns of wartime violence rather than a unique campaign of systematic extermination.

Teachers who used these materials often believed they were providing more balanced historical perspectives that helped students understand the complexity of wartime experiences.

Many had no idea they were actually implementing carefully designed propaganda that served to rehabilitate Nazi ideology by making it seem less exceptional and more understandable as a product of its historical circumstances.

The network’s approach to Holocaust education reveals their sophisticated understanding of how historical memory shapes contemporary political attitudes.

By gradually altering how young Europeans understood their continent’s darkest period, they could influence how future generations viewed related issues like immigration, multiculturalism, and European identity.

General Hinrich von Waldahberg’s mountain fortress has finally surrendered its secrets after nearly eight decades of silence.

What began as one man’s desperate attempt to escape justice evolved into something far more sinister.

A shadow network that spent generations quietly infiltrating European society.

The discovery forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth.

Sometimes the most dangerous enemies are those who refuse to accept defeat, choosing instead to wage war through patience, influence, and the slow corruption of democratic institutions.

The mountains may have claimed von Waldberg, but his legacy reminds us that vigilance against extremism is not just a lesson from history.

It’s an ongoing responsibility for every generation.

This story was brutal, but this story on the right hand side is even more insane.

News

🐘 Nike’s Shocking Choice: Alex Eala’s $45 Million Contract Leaves Sabalenka in the Shadows! 🌪️ “One moment in the spotlight can change everything!” In an unexpected twist, Nike has announced a groundbreaking $45 million contract for tennis prodigy Alex Eala, effectively sidelining Aryna Sabalenka. As the tennis world buzzes with speculation, the implications for both athletes are immense. Can Sabalenka reclaim her position, or will this snub redefine her career? The drama unfolds as the competition heats up! 👇

The Shocking Snub: Nike’s $45 Million Contract for Alex Eala Leaves Aryna Sabalenka Reeling In a dramatic turn of events…

🐘 Revenge Motive Explored: Forensic Expert Raises Alarming Questions in Guthrie Case! ⚡ “The past has a way of catching up with us, especially in matters of revenge!” A renowned forensic expert has put forth a chilling theory that revenge may be a key motive in the ongoing investigation of Nancy Guthrie’s case. As the implications of this theory unfold, the community is left to ponder the relationships and rivalries that could have led to such a drastic act. Will this insight lead to the breakthrough everyone has been waiting for, or will it deepen the mystery? 👇

The Dark Motive: Revenge Uncovered in the Nancy Guthrie Case In a shocking revelation that feels like the climax of…

🐘 Emergency Alert: Boeing’s Departure from Chicago Sends Illinois Into a Frenzy! 💣 “Sometimes, the sky isn’t the limit—it’s the beginning of a downfall!” In an unprecedented move, Boeing has announced it will shut down its Chicago operations, leaving the Illinois governor scrambling to manage the fallout. As uncertainty looms over thousands of jobs and the local economy, the political ramifications are vast. Can the governor stabilize the situation, or is this just the beginning of a much larger crisis? The clock is ticking! 👇

The Boeing Exodus: Illinois Governor Faces Crisis as Jobs Fly Away In a shocking turn of events that has sent…

🐘 Nancy Guthrie Case Takes a Dramatic Turn: New Range Rover Evidence Discovered! 🌪️ “Sometimes, the truth rides in style!” In a shocking turn of events, authorities have unearthed new evidence related to a Range Rover that could change everything in the Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, questions abound: what does this mean for the timeline of events? With emotions running high and the community demanding answers, the stakes have never been greater. Will this lead to a breakthrough, or is it just another twist in a long and winding road? 👇

The Shocking Revelation: New Evidence in the Nancy Guthrie Case Changes Everything In a gripping twist that feels ripped from…

🐘 Lawmakers Erupt: Mamdani’s Deceitful Campaign Promises Under Fire! 💣 “Trust is the currency of politics, and Mamdani is bankrupt!” In a dramatic clash, lawmakers have slammed Mamdani for betraying the trust of New Yorkers with his hollow promises. As the investigation unfolds, the community is left in shock—what does this mean for the future of leadership in the city? With public confidence at an all-time low, the pressure is on Mamdani to make amends or face the consequences of his actions. The clock is ticking! 👇

The Reckoning: Zohran Mamdani’s Broken Promises and the Fallout In the heart of New York City, a storm is brewing…

🐘 Major Breakthrough: Range Rover Linked to Nancy Guthrie Case Investigation! 🕵️♀️ “The truth is often stranger than fiction!” In an unexpected turn of events, police are now investigating a Range Rover in connection with the high-profile Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, new leads are emerging that could change everything we thought we knew. What role does this vehicle play in the unfolding drama? The public is on high alert, and the quest for justice has never been more urgent! 👇

The Dark Turn in the Nancy Guthrie Case: A Range Rover and a Web of Secrets In the unfolding drama…

End of content

No more pages to load