A couple on their honeymoon disappears along the most photographed stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway.

Their car was found with the engine still warm.

Wallets inside.

No signs of struggle.

The only clue, a single photo posted online showing a background that doesn’t exist.

18 years later, a retired highway patrol officer notices something in the photo no one ever caught before.

What happened at mile marker 12? Subscribe for more cinematic true crime stories where the past never stays buried.

August 3rd, 2005.

Location: Pacific Coast Highway, California.

Mile marker 12.

The ocean was calm that morning.

A thin marine layer clung to the cliffs like a secret it wasn’t ready to tell.

Sea mist rolled over the winding ribbon of highway, muting the dawn light, softening the jagged coastline into something ghostly.

It was the kind of morning that seemed to belong to no one, where time slowed down just enough for people to disappear.

At exactly 6:17 a.m., a trucker named Ed Callahan pulled onto the shoulder at mile marker 12 to relieve a throbbing migraine.

He stepped out of his rig, blinked at the blur of fog over the Pacific, and took two aspirin with lukewarm coffee from a dented thermos.

When he looked back toward the road, he noticed something that hadn’t been there the last time he passed.

A pale blue 2002 Toyota Camry parked too neatly, too deliberately.

He didn’t see anyone inside.

The windows were up, headlights off.

The car didn’t look crashed or abandoned.

It looked paused as if the owners had simply stepped out and meant to return.

He would remember that phrase later, “Ment to return, because no one ever did.

” By 9:43 a.

m.

, CHP Officer Nicole Arieta arrived on scene after a call from a passing motorist flagged the vehicle as suspicious.

The blue Camry hadn’t moved.

It was parked two feet off the asphalt, front tires aligned perfectly with the white shoulder line.

Engine cool.

She approached with standard caution.

Glanced inside.

No driver, no passenger.

Two cell phones resting on the center console.

A pair of sunglasses on the dash.

Two half empty water bottles in the cup holders.

Back seat empty.

Trunk locked.

Inside the glove box, insurance papers and registration.

Owner James E.

Hartwell, age 29.

Passenger Emily Rose Hartwell, aged 27, his wife of 12 days.

Their wallets were found in the driver side door pocket, IDs facing up, but there were no keys, no footprints in the gravel shoulder, no note, no sign of panic or violence, just the soft hiss of waves breaking below and the hum of traffic curling along the cliffs.

indifferent.

Nicole walked 50 yard in each direction.

She saw nothing unusual until she looked up toward the cliff wall behind the turnout.

Embedded in the craggy surface was a faint mark, like someone had pressed something flat and circular into the dirt.

It looked fresh.

Below it, a scattering of tiny crushed seashells out of place so far above the shoreline.

She photographed the scene, filed her initial report, requested a tow.

At 11:12 a.

m.

, the Heartwells were officially declared missing.

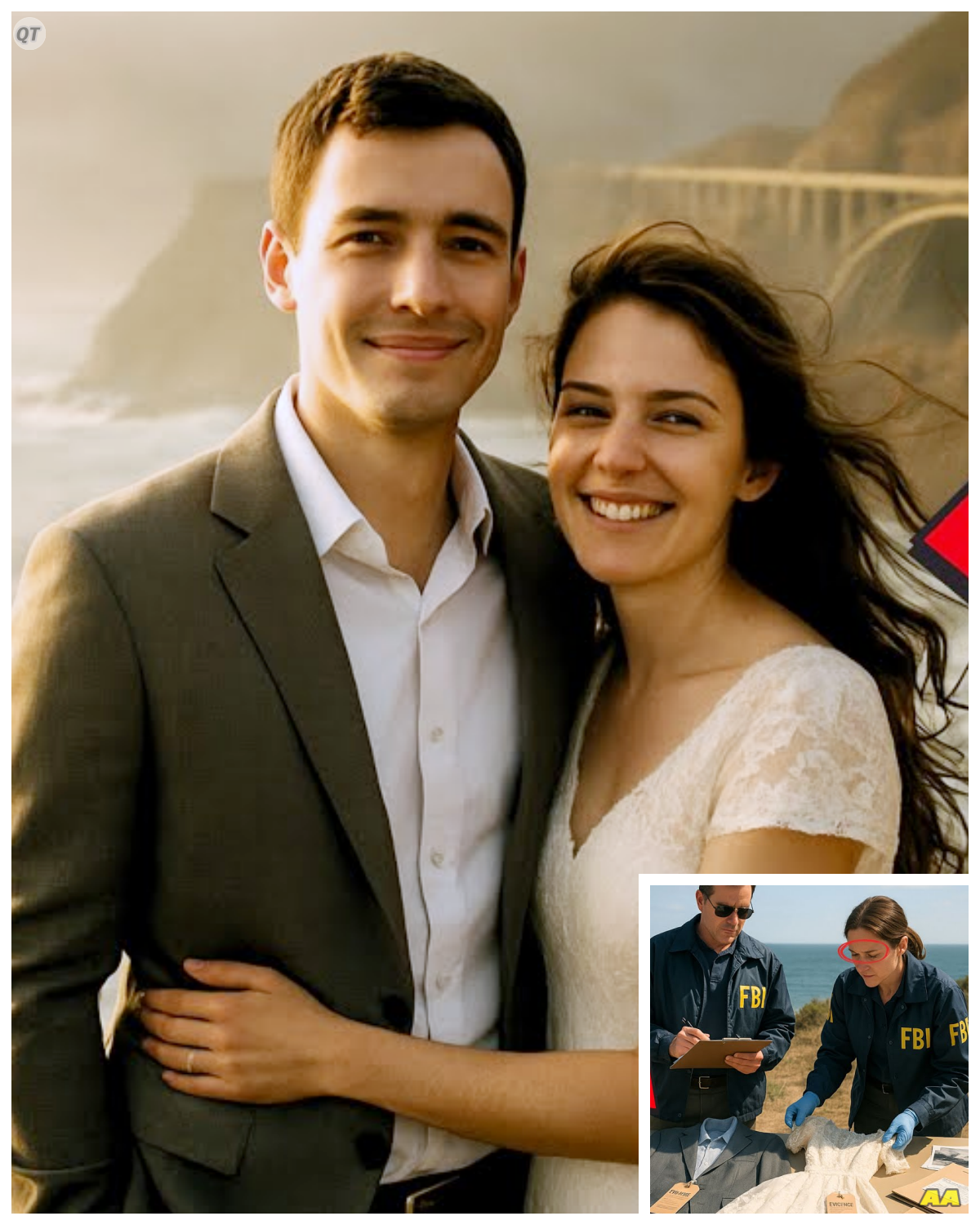

By sunset, their names were circulating on local news stations, accompanied by a cheerful photo from their wedding just two weeks prior.

He wore a gray suit.

She a lace dress with wind tangled curls.

Both laughing with their heads tilted back, arms outstretched.

In the background of that photo, tucked in the far corner, barely visible between the trees, was a shape no one noticed at first.

Not until years later, and by then it was already too late.

July 18th, 2023.

Location: Pacific Coast Highway Archives Division, Ventura County, California.

The Heartwell file was in the wrong drawer.

It shouldn’t have mattered.

cases that cold had long since settled into the forgotten strata of bureaucracy.

But for retired CHP investigator Howard Lane, it mattered more than anything else.

He wasn’t supposed to be at the archives building that morning.

His badge had been retired for 5 years.

His office was now a garage with half a fishing boat in it and a radio that only played baseball.

But the Heartwells still kept him up at night.

He had driven that stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway thousands of times since 2005.

Knew every blind curve and landslide scar by memory.

But mile marker 12, that turnout, that Camry, that perfect bloodless crime scene had never left him.

In all his years with the highway patrol, Lane had dealt with more than his share of tragedy.

Jumper calls from Bixby Bridge, cars blown into the sea, even a body found zip tied in a culvert pipe.

But James and Emily Hartwell didn’t make sense.

And in law enforcement, that kind of silence gets under your skin.

Lane stood now in front of the industrial metal drawer labeled 2005 incident reports coastal sector, and tugged it open with both hands.

Dust bloomed into the air, acurid and familiar.

He flipped past folders.

Wrecks, suicides, citations, minor thefts.

No heartwell file.

He swore quietly, leaned down, and opened the drawer below.

Nothing.

Then one more down.

There, wedged sideways behind an oversted file labeled wildlife hazards.

Gaviota Pass, he found it.

a weathered Redwell folder with the tag Hartwell James and Emily.

PCHMM12 missing persons unresolved.

He pulled it out slowly, almost reverently.

The folder was heavy with photographs, intake reports, search grids, and dozens of clippings.

Everything was right where he remembered, except for the print out of the last known photo posted by James to their travel blog on August 2nd, 2005.

The photo had been dismissed early on.

A smiling selfie of the couple perched at a scenic overlook, the Pacific curling in the background.

They were happy, windswept, sun drenched.

It had been timestamped 5:49 p.

m.

, just 12 hours before their car was found empty.

Investigators had determined it was taken somewhere between Carmel and Big Su, but no one had been able to match the exact location until now.

Lane held the photo under the archival lamp, squinting.

Something in the background had caught his eye, something he hadn’t noticed before.

The coastal cliffs behind them had always seemed familiar.

But it was the rock formation just behind Emily’s right shoulder that brought a pulse of adrenaline into Lane’s chest.

A long flat slab, horizontal, fractured at a 45° tilt, just visible between the blur of windb blown hair and ocean spray.

He had seen that rock before, not on any tourist trail, not in any photo archive in real life and not once, twice.

He reached for his notepad and started sketching.

Then he opened the county’s coastal development survey maps from 2005.

There, the rock slab was part of a forgotten service road blasted into the cliffside during construction repairs from a mudslide years earlier.

It had been sealed off in 2006 after erosion made it impassible.

But in August of 2005, it had still been accessible roughly 3 mi south of mile marker 12.

Lane circled it on the map.

Then circled the date again, August 2nd.

If they had been there, if that photo was from that location, then every theory about where they vanished fell apart because they were never at mile marker 12.

Not when the photo was taken.

The next morning, Lane drove south.

He didn’t tell anyone, didn’t notify local PD.

He wasn’t a cop anymore.

He just wanted to stand on that spot, see it with his own eyes.

It took him an hour of driving, winding, nauseainducing roads before he reached the barricaded gate.

The old service road looked like a dried vein snaking through coastal sage brush, eroded, forgotten, barely wide enough for a single vehicle now.

He parked his truck, climbed over the rusted chain, and started walking.

His knees achd, his back protested, but as he rounded a curve that overlooked the sea, he stopped dead.

There it was, the fractured slab of rock, the one from the photo.

And lying at the base of the slab, partly buried under windb blown silt and sea debris, was a warped sunbleleached lens filter, the kind that attaches to a digital camera.

laying crouched down, picked it up gently with a handkerchief, etched in the rusted metal rim, almost invisible, was the brand.

Canon 58 mm UV, Japan.

The same lens brand listed in the Hartwell’s missing electronics report, the one attached to the camera that was never found.

He didn’t speak, just stood there, letting the surf crash below him.

For 18 years, they’d believe the Heartwells vanished at mile marker 12, but they were three miles south, and someone had gone to a lot of trouble to make sure nobody ever knew that.

July 21st, 2023.

Location, Ventura County Sheriff’s Office.

Cold case division.

The room smelled like old carpet and burnt coffee.

Detective Marin Reyes sat behind a steel desk beneath buzzing fluorescent lights, flipping through a cold case intake sheet.

The words reactivation request.

External were stamped in red at the top and the name Hartwell was scrolled in the center margin in a familiar looping hand.

She raised an eyebrow.

Reyes had inherited the cold case division two years earlier.

She was 43, relentless and patient to a fault.

Where others saw hopeless stacks of paper, she saw unresolved patterns.

And she knew the Hartwell case.

Everyone in Ventura law enforcement who’d been around long enough did.

The couple who’d vanished with no trace and no struggle parked like statues in the morning fog.

But that case had been closed in everything but name.

She tapped her pen against the intake sheet and looked at the attached note from Hlane.

Retired CHP discovered evidence inconsistent W original scene location.

Request re-evaluation of MM12 as true sight of disappearance.

Possible photo analysis discrepancy.

Recovered artifact at undocumented service turnout.

Possible camera component.

Believed link to Heartwell belongings.

Can we talk? Reyes leaned back in her chair, the pen stilled between her fingers.

She remembered Lane vaguely, one of the old ghosts, retired officers who never fully left the job behind.

The ones who kept poking around cases that no longer made headlines, usually harmless, sometimes obsessive.

But this wasn’t nothing.

She picked up the evidence bag attached to the file.

Inside was the lens filter Lane had mailed in.

A faded Canon 58mm UV partially rusted.

She slipped on gloves, opened the seal, and carefully tilted it under the desk lamp.

There was sand lodged in the threads.

A hairline fracture in the glass and on the outer rim.

Something else barely visible.

E.

Hartwell, April 5th.

Scratched in by hand.

personal, a label of ownership.

Reyes sat up straighter.

The heart wells had vanished on August 2nd, 2005.

The camera had been logged as one of the missing items.

This filter had been signed and dated 4 months before they disappeared.

That wasn’t something you planted.

That was something that got lost or buried.

She picked up the phone and dialed a number from memory.

Lane.

A voice answered after two rings.

It’s Reyes, she said.

I got your envelope.

A pause.

I figured you might.

Where did you find this? That old turnout they shut after the landslide in ‘ 06, just south of marker 12.

The one that never made it on the Calrans maps.

You’re sure it’s the place in the photo? I stood there myself.

Rock angle background elevation.

Everything matches.

And that filter? It was lying right under the slab, just barely visible.

Reyes exhaled slowly, staring at the image again.

“If you’re right,” she said.

“Then the car wasn’t left where the incident happened.

” “Nope,” Lane said.

“Somebody moved it.

” By noon, Reyes was driving the stretch of PCH between Big Su and Cambria, retracing the Heartwell’s last known movements.

She stopped briefly at mile marker 12, a quiet coastal pullout that felt more like a lookout for fog than anything sinister.

The shoulder had long since been repaved, and tourists now took selfies here without knowing they were standing where a ghost story began.

Then she continued south past a chainlink gate half swallowed by salt brush and pulled over.

A rusty Calran sign hung crookedly.

Road closed.

Unstable grade.

No entry.

Reyes slipped through the gap.

The old service road still clung stubbornly to the cliff.

Chunks of gravel and seaweed crunching under her boots.

The wind howled like something wounded.

She walked a quarter mile, then stopped when she saw the fractured rock slab.

Just like the photo, she turned in a slow circle matching landmarks, the shape of the coastline, the position of the horizon, the rock, the angle of the couple’s selfie, the sea behind them.

It all fit.

This was where the last photo was taken.

She crouched where Lane had found the filter, brushing back loose sediment.

Nothing else immediately caught her eye.

But that didn’t matter.

The damage was already done.

If the Heartwells had been here at sunset on August 2nd, and their car was found parked miles away the next morning, then someone had moved the vehicle, which meant someone else had been with them that night, and they’d let the world believe it was just a disappearance.

Back at the office, Reyes reopened the original missing person’s file.

At the time, it had been ruled a no crime disappearance.

No blood, no sign of struggle.

The theory had gone like this.

The newlyweds went for a walk along the cliffs, slipped, fell, and were swept out to sea.

A tragic accident.

An open-ended ending.

But now the theory no longer held.

She looked at the property log.

The camera had never been found.

Neither had James’s digital planner, nor Emily’s silver necklace with the engraved E plus J charm, but both cell phones had been left behind in the car.

Someone had made sure the scene looked like an accident.

Reyes stood and walked over to the evidence cabinet.

She unlocked the drawer labeled Heartwell, slid it open, and pulled out the original photographic analysis report.

She laid the selfie under a new forensic light.

The digital contrast enhancement brought up what Lane had missed and maybe what investigators had missed too.

Between the couple in the far background, there was a blurry vertical shape in the shadows.

At first glance, it looked like a shrub or tree.

But when she magnified it and adjusted the lighting balance, it looked like a person just barely visible standing behind them.

Not posing, not smiling, just watching.

July 22nd, 2023.

Location, San Louis Abyispo County, Hartwell family residence.

The house sat on a quiet culde-sac in a royal grande.

The porch shaded by Bugan Villia that hadn’t bloomed in years.

The Hartwell name was still on the mailbox, though only one parent remained.

Margaret Hartwell opened the door slowly, her back slightly hunched, but her eyes sharp behind wire- rimmed glasses.

She didn’t ask who Detective Reyes was.

She didn’t need to.

The name badge, the car idling in the driveway, the look in the woman’s eyes.

She’d seen it all before, but not for a long time.

“Come in,” Margaret said quietly.

“You’ll want tea.

People always want tea when they come to talk about Emily.

Inside, the home was tidy and dim, preserved like a museum.

Reyes noticed the framed wedding photo of James and Emily, still perched on the mantle, the one the newspapers had run for weeks.

James, with his hand on Emily’s waist, her bare feet in the sand, a Pacific sky behind them, cloudless and endless.

They were married in big su, Margaret said as she poured hot water into two cups.

Right where they disappeared.

Poetic, I suppose, if you believe in that sort of thing.

Reyes sat down at the kitchen table, placing a soft evidence folder between them.

I’m not here with answers, she said gently.

Not yet, but we’ve reopened the case.

Something’s changed.

Margaret didn’t flinch.

She stirred her tea without drinking it.

changed how Reyes slid a photograph across the table, the enhanced image of the selfie, James and Emily in the foreground and in the far background, the blurred vertical shadow.

Margaret leaned forward.

“That wasn’t there in the original photo,” she murmured.

“It was always there.

We just didn’t see it.

No one enhanced the image this far back in 2005.

We were limited by the tech.

” Margaret stared at the image for a long time.

It’s not James, she said softly.

Not his shape, not his posture.

You’re sure? I’m his mother.

I’m sure.

Reyes nodded, letting the silence stretch.

Margaret’s fingers trembled slightly as she reached for the photo again, as if touching it might shake something loose from memory.

“There’s something else,” Reyes said after a beat.

this location where the photo was taken.

It wasn’t mile marker 12.

Margaret looked up confused.

It was farther south on a sealed off turnout, abandoned after a landslide.

The road was unstable and shut down in 2006, but in August 2005, it was still passable.

Someone took them there and then moved the car.

The color drained from Margaret’s face.

You’re saying it wasn’t an accident? I’m saying someone went to a lot of trouble to make it look like one.

Margaret stood up and crossed the room.

Her movement slow but deliberate.

She opened a drawer and pulled out an old manila envelope creased, yellowed, and held shut with a paperclip.

She laid it on the table.

“I wasn’t sure I should keep this,” she said.

After a while, I felt like maybe I was clinging to it because it was something.

But now she opened the envelope and spilled the contents onto the table.

Inside were two Polaroids, a folded receipt, and a note handwritten in block letters.

Reyes picked up the first photo.

It showed James and Emily seated at an outdoor cafe sipping drinks, happy, relaxed.

That’s from their road trip, Margaret said.

Emily mailed it from a motel in Monteray.

It arrived 2 days after they were reported missing.

just late enough to feel like a cruel joke.

Reyes turned the photo over.

On the back, Emily’s handwriting read, “Wish you were here.

” We made it to the cliffs.

Sunset tonight.

Love M.

The second photo was a shot of a journal page, zoomed in, almost clinical.

The handwriting looked like James’s.

One sentence had been circled three times in red ink.

We saw someone again.

Same guy from the last turnout.

He keeps pretending not to watch us.

It’s creeping him out.

Reyes felt her pulse tick up.

Did you show this to the investigators back then? I did.

They filed it.

Said it was probably nothing.

A passing hiker.

No one matching that description ever came forward.

And the receipt.

Margaret passed it over.

Reyes unfolded it carefully.

a hardware store slip dated July 29th, 2005, just 4 days before the couple vanished.

Purchased items: tarp, rope, flashlight batteries, a pair of utility gloves, and a folding spade.

The name on the card, El Granger.

Reyes sat up straighter.

Who’s that? I have no idea, Margaret said.

But that receipt was in James’s hiking journal when his things were returned.

The officer told me it probably belonged to someone else.

Said it got mixed up.

But what if it didn’t? Reyes stared at the name.

In any other case, this might have been noise.

Just background static, but not in this one.

Someone else had been watching the Heartwells.

Close enough for James to notice.

Close enough to be written down.

And now, 18 years later, a name had finally surfaced.

El Granger.

Later that evening, back at the department, Reyes ran the name through the DMV and state databases.

Nothing came back.

Then she narrowed the search to business owners in coastal San Louis Obyspo County in 2005.

It took nearly an hour, combing through old permit records and contractor applications.

Then it hit.

Granger Lewis B contractor license expired.

owner of Granger Coastal Repair and Grading, a one-man operation hired in 2004 by Calrans for landslide mitigation near the old service road south of MM12, the exact turnout where the last Hartwell photo had been taken.

Reyes leaned back in her chair, the room suddenly very still.

A man who had access, a man who knew the roads, a man who was there, exactly when and where the couple disappeared.

She opened a new case file.

Subject: Lewis B.

Granger.

Status: Person of interest.

Priority one.

July 23rd, 2023.

Location, San Simeon, California.

Granger Coastal Equipment Yard.

Abandoned.

It was just a rust heap now.

A gate hung lopsided between two leaning fence posts, choked in dune grass, and welded shut by years of salt air.

Behind it, the lot stretched out like a graveyard for broken machinery, back hoes with missing treads, cement mixers speckled with bird droppings, rust bitten pipes tangled in brittle weeds.

Detective Reyes stood at the edge of the yard, the Granger file tucked under her arm, her badge clipped at her hip.

She wasn’t here with a search warrant.

Not yet.

But this wasn’t private property anymore.

According to tax records, the land had been forfeited for back taxes in 2011.

It was a dead place, just like the man she was looking for.

Lewis Bernard Granger, born 1951, no children, never married, lived alone in a trailer on the inland side of Route 1, disappeared from his known address in 2006, barely a year after the Hartwells vanished.

No forwarding address, no death certificate, no proof of life, a quiet exit, the kind a guilty man makes.

Reyes stepped over the fence and into the lot.

The wind rattled loose siding against an overturned tank.

Nothing moved but a startled gull that flapped off the shell of a rusted water truck, but there was a building in the back.

Long rectangular sheet metal walls rippled from salt storms.

A lock hung on the door, corroded but intact.

Reyes knelt and pulled a thin pry bar from her satchel.

Two minutes later, the lock snapped.

The metal door creaked open into the stale air of a storage office, untouched for nearly two decades.

She stepped inside.

The dust hit first.

thick fungal like paper rot and sea mold.

But the light from her flashlight cut through it cleanly, illuminating a desk buried under blueprints, contractor logs, and half-colapsed cardboard boxes.

Everything was water damaged, some of it illeible, but it was here.

This was Grers’s base, the last place he worked before falling off the map.

Reyes scanned the shelves.

stacks of cassette tapes, worn equipment logs, a Calrans vest hung like an afterthought on a bent nail in the wall.

Then something caught her eye.

Tucked in a wire rack near the window, a weathered project binder with a yellowed label peeling at the corner.

Job number 7405, slope stabilization, coastal sector MM11 to13.

She opened it.

Inside were site photos taken between May and July 2005 documenting landslide cleanup, culvert repair, and graded road shoulders.

One of the photos showed the same fractured rock slab from the Heartwell’s final selfie.

The margins were filled with hands scribbled notes, dates, supplies, personnel names.

Most were standard until one entry dated August 3rd, 2005 caught her breath.

Check turnout after rain.

Tire ruts still visible.

No work scheduled.

Fresh bootprints beyond road line.

Didn’t report.

Didn’t report.

Why? Reyes scanned the rest of the page.

Nothing else written that week.

The next entry wasn’t until the following Monday.

And under the binder’s final divider was a folded sheet of notebook paper that felt out of place.

She opened it.

A list.

two names at the top, James Hartwell, Emily Hartwell, and beneath them, columns of details, vehicle, route, license plate, notes about where they’d stopped, local trail heads, restaurants.

It read like surveillance, like someone had tracked them.

Near the bottom, last scene, August 2nd, sunset, saw camera.

Beneath that, three words scrolled in different ink.

They knew me.

Rehea stood frozen in the halflight.

Then the sound hit her, a soft metallic clang, like something shifting deeper inside the building.

She snapped off her flashlight and went still.

No birds, no wind now.

Then another sound.

Scrape.

Scrape.

It was coming from the back room.

She moved slowly, hand brushing the grip of her sidearm.

The door to the rear office was partially open.

The hinges twisted from heat warping.

She nudged it wider with the tip of her boot.

And there, lit only by the dust haze filtering through a single cracked skylight, was a cot, a thin blanket, an overturned can, a jar of peanut butter, footprints in the dust, fresh, a plastic jug half-filled with water.

Someone had been living here recently.

She turned in a slow circle, heart climbing her ribs.

No power, no plumbing, no vehicle outside, but someone had been staying in Grers’s yard.

Someone who knew this place, who knew the roads.

She stepped back out into the light, scanning the coastline.

It wasn’t just about the Heartwells anymore.

Back in her car, Reyes radioed dispatch.

I need a search unit at 721 Coastal Yard, San Simeon, abandoned contractor site.

Possible evidence of habitation and send a forensic team.

There’s handwriting samples and job logs I need processed.

She paused and put out a local APB named Lewis Bernard Granger, now listed as missing.

Suspicious circumstances, may still be alive.

Later that night, in her apartment, Reyes spread the evidence on her kitchen table.

The grainy image of the man in the background, the lens filter, the Polaroid from Emily, the receipt, the field note.

They knew me.

And now someone possibly squatting at Grers’s last known location.

Reyes pulled up Google Earth on her laptop and typed in mile marker 12.

She stared at the digital coastline.

Somewhere near that turnout, hidden beneath time, was the answer.

Not just to where the heart wells went, but why.

And someone still alive might be ready to make sure that truth stayed buried.

July 24th, 2023.

Location, Pacific Coast Highway.

Near mile marker 11.

8.

The morning marine layer still hadn’t lifted.

A curtain of wet fog draped the cliffs.

The waves below muffled like a held breath.

Detective Reyes parked her cruiser near the crumbling shoulder just under a faded Calr sign reading no access unstable grade.

This was it.

The hidden turnout.

The one Granger had visited on August 3rd, 2005.

The one the Hartwells had photographed the night before they vanished.

The old path was half consumed by wild mustard and waist high coastal sage, but the fractured rock slab was unmistakable, just like in the photo.

She stepped out, boots crunching gravel, and began to trace a slow arc along the edge of the cliff.

Her eyes were sharp, trained not on the obvious, but the subtle, the breaks in nature’s rhythm, the signs that someone had been here before her.

Then she saw it.

A sunken depression in the ground, three paces off the main turnout, oval-shaped, overgrown, but too symmetrical to be natural.

Reyes knelt and brushed away the top soil.

Within seconds, her fingers struck wood.

She froze, glanced around, nothing but the fog in the sea.

She kept clearing, slow, careful strokes until she revealed the rough grain of an old hatch.

marine plywood, weathered, warped, nailed down with square cut, rusted nails that didn’t match modern construction.

She stepped back and radioed it in.

An hour later, the forensic team arrived.

They cordoned off the area and brought in the mobile scanner.

Ground penetrating radar lit up the screen with a ghostly silhouette beneath the soil.

A chamber roughly 8x 10 ft buried 6 ft deep.

No ventilation, no light, no way out from the inside.

By 3:40 p.

m.

, they had uncovered the full hatch.

The wood groaned as they pried it open.

The smell hit first.

Old rot, mildew, something coppery beneath.

Reyes pulled on gloves and descended the short ladder, flashlight cutting through the dark, and what she found made her blood run cold.

Inside the chamber, a metal folding chair tipped over on its side, a pair of zip ties on the ground, frayed, the faint outline of a shoe print in the hardened dirt and pinned to the wall with a rusted nail, a single torn polaroid.

It was a close-up blurred off angle, but Reyes could make out two things.

A woman’s mouth gagged, and next to her, a man’s hand with a wedding ring.

Later, back above ground, Reyes stepped aside as the evidence team cataloged the scene.

She stared at the Polaroid, bagged and tagged.

Emily and James Hartwell had been here, and they hadn’t been alone.

Back at the department that evening, Reyes dug deeper into Lewis Granger’s history.

She found something odd.

Between 1997 and 2002, Granger had filed multiple permits for hillside drainage repairs and private road grading, always within a three-mile stretch of the PCH.

Some had been completed, others never inspected.

Many had faded from public record.

She requested access to the archived blueprints.

Within 30 minutes, a pattern emerged.

He wasn’t just fixing roads.

He was building offshoots, narrow, unmarked paths carved into blind switchbacks and cliffside crevices.

One of those paths led straight to the hidden chamber.

10:12 p.

m.

Reyes stared at a wall in her apartment now covered in case photos, maps, and red yarn connections.

One photo haunted her.

The last picture from James Hartwell’s blog.

The smiling couple.

The Pacific.

the slab of rock and that blurred figure in the background.

A man watching from the edge of the cliff, not waving, not posing, just standing there still as death.

And if Lewis Granger hadn’t been the one living in the equipment yard recently, then who was? July 25th, 2023.

Location San Louis Abyspo County Records Department.

archive level.

By midm morning, Reyes had returned to the records department’s lower archives, where the air never changed and the fluorescent lights buzzed like insects.

She pulled a rolling ladder beside the wall labeled 2000 to 2006 private contractors and climbed halfway up to the third drawer.

The cabinet groaned open, revealing dozens of aging files thick with carbon paper, handwritten invoices, and grease stained permit copies.

She wasn’t after permits this time.

She was looking for people, specifically the ones who helped Lewis Granger do what he did.

People who wouldn’t show up in official reports because they never left enough of a trace.

It took nearly an hour to cross reference the contractor logs with unregistered labor records.

That’s when she found it.

A yellowed nearly illeible ledger entry under the 2004 slope project.

Job number 7405.

The same site that spanned mile markers 11 through13.

Helper B.

Marorrow cash day labor referred by El Granger.

The handwriting was messy, but the name leapt off the page like a flare.

Brendan Marorrow.

never once mentioned in the 2005 investigation.

Never interviewed.

She pulled out her laptop and ran a background check.

At first, nothing.

No taxes, no criminal record, no social media presence.

But buried in DMV records, she found a registered trailer address, Craig Hollow Road, west of Atascadero.

The last activity tied to that address had been a utility shut off in 2010, but the place hadn’t been condemned, and that meant it was still out there.

By 3:30 p.

m.

, Reyes was already halfway through the winding oak covered roads that led out of town, the address punched into her dashmounted GPS.

The deeper she drove, the less cell reception she had.

Just before 4:15 p.

m.

, Reyes spotted the trailer.

A faded green box behind a leaning split rail fence, surrounded by rusted out metal parts and broken furniture.

A crumpled leanto shed sat collapsed to one side, and a dented burn barrel smoldered faintly nearby.

She parked off the road and approached slowly, one hand near her sidearm.

The front of the trailer looked abandoned, but someone was out back.

A barefoot man sat in a folding chair behind the trailer, shirtless despite the shade, stirring the embers in the burn barrel with a piece of rebar.

His head was shaved and his skin looked waxy, sun damaged slack.

Brendan Marorrow, Reyes called.

He looked up but didn’t answer.

I’m Detective Reyes, San Louis Oispo County.

She kept her tone calm, steady.

I’d like to talk about Lewis Granger.

Maro stared at her for a long moment, then said flatly, “Lewis is dead.

” Her heart rate ticked upward.

“How do you know that?” “He told me.

” She moved closer, keeping her boots in the dirt.

“When did you last see him?” He stirred the ashes again.

“After the girl screamed.

” Reyes went still.

“What girl?” Maro blinked slowly as if shaking loose from a trance.

I didn’t know her name.

He didn’t tell me names, just tasks.

What kind of tasks? Digging, moving rock, building a trap door.

I wasn’t supposed to ask questions.

He kept poking the fire, eyes half-litted.

He said the girl screamed the whole first night.

That’s why he moved them.

He didn’t want anyone hearing it.

Rehea stepped carefully around the barrel.

You helped him build the chamber under mile marker 12.

We built more than one, he said softly.

He called them rooms for the gone.

Sunlight had begun to tilt golden across the tops of the trees by the time Reyes had Brendan Marorrow seated on the porch of his trailer, hands resting on his knees.

He seemed calmer now.

Not cooperative exactly, but detached.

She pressed further.

How many rooms? He shrugged.

Three, maybe four.

And where are they? His head tilted toward the hills.

One’s out past the well line, another beneath the old goat barn, but he moved some, sealed others.

Reyes leaned forward slightly.

Did he ever bring anyone else out here? Maro didn’t answer.

Instead, he looked toward the treeine and said quietly he liked the echo.

Said, “If you whisper in the dark long enough, the ground listens.

” Reyes backed away and keyed her radio.

I need a team at 981 Craig Hollow Road.

Possible suspect tied to multiple unlawful burial sites.

Bring ground sonar and cadaavver dogs and backup.

By dusk, the mobile unit had arrived and the dogs were sweeping the back lot.

Just after 8:00 p.

m.

, one of the handlers whistled for Reyes.

Dog team Axel had stopped near a rusted water tank buried in brush.

The sonar confirmed it.

There was a cavity below.

They started to dig.

Within the hour, a second hidden chamber was uncovered.

This one deeper than the first, with a warped plywood hatch reinforced with wire mesh.

The interior was narrow, tunnneled into the earth, barely tall enough to stand.

Inside, Reyes found a single wooden chair, splintered and damp.

A broken music box crushed beneath its legs and carved into one of the wall supports over and over.

Emily.

She stared at it for a long time.

Someone had survived down here, for at least a while.

Later that night, Brendan Marorrow sat silently in the back of the cruiser, hands cuffed but loose in his lap.

He hadn’t resisted, hadn’t spoken since the dig.

As Reyes closed the door, he whispered just one more word through the cracked window.

Blue house.

She turned.

What does that mean? He didn’t answer.

Just stared into the trees.

Reyes stood still as the cruiser drove away.

The chamber beneath mile marker 12 had been one secret, but now it was clear.

There were more, and someone had named them.

Rooms for the gone.

July 26th, 2023.

Location: St.

Louis Abyispo Sheriff’s Department cold case unit.

By sunrise, Reyes had already brewed her second cup of coffee and pinned a new word above the crime board.

Blue House.

She stood facing it, surrounded by photos of the heart wells, the Polaroid from the underground chamber, Grers’s permit maps, and a grainy still of Brendan Marorrow sitting by his fire pit.

What was the blue house? Was it a place? A nickname? A memory twisted by time? She scoured through every recorded structure in San Louis Abyispo County that had ever been painted blue.

homes, churches, camp buildings, oceanfront rentals.

Most were irrelevant.

Some were torn down years ago, but one stood out.

A vacation property on the coast.

Pale blue clapboard siding, faded white shutters about 20 minutes south of mile marker 12.

It hadn’t been rented out since 2006.

The owner was listed as a Shell LLC, one that used to be tied to a company Granger subcontracted through for road maintenance.

Reyes didn’t wait for a team.

She grabbed her camera, her badge, and drove straight to the coast.

By 8:40 a.

m.

, she was standing in front of the house.

It didn’t look like much.

Peeling paint, a warped porch, dead grass curled along the foundation, no tire tracks, no signs of activity in years.

But it was the color that chilled her, not bright beach blue, muted, almost gray in the early light, the kind of blue that photographs differently depending on the film used.

She pulled out the Heartwell’s final blog photo again, zoomed in, that strange gray blue smudge in the upper corner, the background no one could identify, it matched the color of this siding.

She walked up the steps and tested the door.

It creaked open inside.

The air was stale, cold despite the sun outside.

Dust floated through shafts of light, and the silence pressed heavy against her skin.

The house was mostly empty.

No furniture except for a single armchair in the living room covered in a sheet.

But the floor creaked wrong.

She paced slowly, heel to toe, tracing the boards.

There, beneath the rug in the center of the room, was a trap door.

Her breath caught.

No lock, no hinges, just a recessed lip and two finger holes.

She knelt, lifted carefully, and peered down into black.

The flashlight revealed wooden steps coated in dust, and something glittering on the dirt floor below.

She descended.

The room was round, not square like the last chamber, and wider than expected, almost 10 ft across.

Carved into the packed earth were initials, dozens of them, some scratched wildly, some carefully etched.

At the far end, pinned to a makeshift bulletin board, was a map, a handdrawn grid of the PCH coastline with red X’s marked at three specific points.

Mile marker 12, Granger’s equipment yard, and this house.

Tucked into the corner of the board was a plastic sleeve containing a roll of 35 millimeter negatives.

Reyes slid it into her evidence bag.

Back in the daylight, she radioed in the discovery and requested a forensic sweep team.

Then she circled around to the back of the property.

Behind a collapsed fence, she found a pile of scorched photo paper, burned film, some images still faintly visible, faces, sky, a woman’s hand.

She knelt and flipped one on the back written in faded ink.

Day five J.

Her stomach turned.

Granger had photographed them, documented their captivity.

She gathered what she could before the wind carried the ash away.

That afternoon, Reyes brought the negatives to the lab.

The tech, an older man named Vince, handled them like glass.

“These haven’t been stored right,” he said.

But I’ll get you what I can.

By evening, five prints were ready, and one made Reyes stagger.

It showed James Hartwell alive, sitting on the floor of what appeared to be the round chamber, eyes half closed, a cloth tied over his mouth.

His wedding ring was still visible, his shirt torn.

Behind him, a pale blue wall, not the first chamber, not the one near mile marker 12.

This photo was taken here in the blue house that night.

Reyes sat in her car outside the department, rain misting across the windshield.

She replayed everything Brendan Marorrow had told her.

The rooms, the echo, the girl screaming, and a question surfaced that she hadn’t asked yet.

Where was Emily buried? They’d found no bones, no blood, no clothing, just carvings, traces.

Had she ever made it to mile marker 12, or had her voice been swallowed somewhere else entirely? She scrolled back through the Hartwell’s blog entries, looked again at the second to last post, taken at dusk just before the final one.

It had been geo tagged.

She hadn’t noticed it before.

35.

1724° north, 120.

7803° west.

She entered it into the map app.

It landed on an unpaved turnoff just south of the blue house.

She zoomed in.

There was nothing marked there, but the satellite view revealed a long shadow, something buried, something square.

July 27th, 2023.

Location, Coastal Bluff Trail Head, south of San Louis Abyispo.

By late morning, Reyes stood at the edge of the bluff trail, the ocean pulse below her muffled by fog.

She adjusted her pack and stepped over the bent chain blocking the old trail head.

The satellite coordinates from the Heartwell’s blog had led her here, half a mile south of the blue house, where the land fell sharply into bramble and dune grass.

There were no markers, no fencing, just silence, the low moan of waves and the feel of something watching.

She moved carefully down the path, tracing the coordinates on her phone, adjusting as the signal flickered.

20 minutes in, the air changed.

The wind stilled.

Even the gulls were gone.

And then she saw it.

A patch of earth flattened unnaturally.

grass stunted.

A faint rectangle traced in the dirt, subtle but deliberate.

She knelt and pressed her palm flat against the center.

It was cooler than the rest of the ground.

Reyes called it in.

Within the hour, the forensic team arrived with ground penetrating radar.

They scanned the area in a grid.

The technician, a lean man with sunburned ears, flagged her down after the second pass.

“We’ve got a void,” he said.

roughly 6 by 8 ft.

Depth is inconsistent.

Shallow on one end, deeper on the other.

Could be a partial collapse.

They began to dig.

2 hours later, the shovel struck wood.

The coffin wasn’t standard.

It looked handmade.

Rough planks nailed unevenly, smeared with black tar for waterproofing.

The smell that followed was immediate, sweet, rancid.

Reyes pulled her shirt over her mouth and peered inside.

It held a body, female, adolescent.

The remains were curled, knees to chest, arms bound tightly with rope now frayed to strands.

No clothing, no ID, only a single bracelet, half buried beneath the bone.

Plastic, blue and white, faded from sun.

She didn’t need a forensics report.

She’d seen that bracelet before in the Hartwell’s photos.

Emily.

Later that evening, back at the department, Reyes sat before the board, eyes burning from lack of sleep.

She’d confirmed the dental records.

The remains in the box belonged to Emily Hartwell.

It had taken 18 years, three sealed chambers, and one whisper from a man stirring ashes to find her.

But James was still missing.

And now she had more questions than answers.

Why was Emily buried separately? Why was James photographed weeks after her estimated death? What had Granger been doing after Emily died? The idea of one killer had always felt clean.

Easy, but now it was unraveling.

She stared again at the photo she’d found at the Blue House.

James Hartwell gagged, hands tied, eyes dull, but alive.

That photo had been taken weeks, maybe months after Emily was gone.

Granger had kept him alive.

But for what? She went back through Marorrow’s interview transcripts, searching for anything she missed.

Then she found it, scrolled in the margin of her notes from the trailer visit.

Lewis liked the whisper, said the soil could remember rooms for the gone, but the ones who stayed too long.

He said they started to change.

Reyes circled it.

Who changed, the captives or Granger? By midnight, she couldn’t sleep.

She got in her car and drove back to the blue house.

She parked down the road, flashlight in hand, and walked to the foundation.

The crawl space beneath the back porch had been sealed by code enforcement long ago, but the boards had loosened since her last visit.

She pried one open and slipped under.

There, in the damp dirt, she found something she hadn’t seen before.

a hollow carved into the wall, stuffed with decaying paper.

She pulled it free.

Journals water damaged, pages stuck together, but some entries still readable, written in two different hands.

The first entries were mundane.

July 7th, brought them food.

She won’t eat.

He stares, sleeps with his eyes open.

July 11th, had to gag her again.

Won’t stop screaming.

July 13th.

She knows her name.

Keeps repeating it.

Then the tone shifted.

A different script.

Uneven, faint.

I don’t know how many days.

No light, no time.

Her voice is gone.

Mine, too.

She didn’t wake up this morning.

He said it’s better this way.

And finally, he says he’s not alone anymore.

Says I’ll understand if I stay.

Reyes closed the notebook and leaned back against the cold earth.

There was more than one voice in this house, and one of them might still be echoing.

July 28th, 2023.

Location: San Louis Abyspo County Forensics Lab.

The autopsy report confirmed what Reyes had already begun to fear.

Emily Hartwell died of asphyxiation.

There were no defensive wounds, no signs of a violent struggle.

No blunt force trauma, just evidence of prolonged restraint, wrist ligature marks, bruising on the upper arms, and positional asphixia likely caused by being bound and placed face down.

The medical examiner estimated her death occurred within 5 to 7 days of her abduction, which meant Emily was dead long before the photo of James was taken.

The implications scraped something raw inside Reyes.

James had not only survived the initial abduction, he had lived through her death.

And someone had kept him alive long after she was buried.

But why? The journals hinted at manipulation, isolation, perhaps even conditioning.

She opened them again that morning and flipped to the final page.

There, scrolled at the very bottom in trembling pencil.

He said, “The longer I stayed, the less I’d want to leave.

” He said I was his mirror.

He said the house would make me just like him.

Later that day, Reyes returned to the blue house with a forensics team.

They had started pulling up the floorboards around the trapped door, excavating the edges of the chamber for further evidence.

One technician found a strip of metal buried behind the staircase, an old ID bracelet.

The name etched into it, James Hartwell.

The strange part was how clean it was, unscathed, untarnished.

It had been placed there deliberately, as if it was meant to be found.

That afternoon, Reyes reviewed old records from 2005 again, looking for any signs Granger might not have acted alone.

One name kept surfacing in contracts, though never as a direct employee.

Marcus Ames, a local handyman.

No arrest record, no fingerprints in the system, but his name appeared beside Grangers in handwritten logs.

Ames had never been interviewed.

She dug deeper.

Ames owned a property just northeast of Paso Rob, an old ranch tucked against the hillside, inaccessible by paved road.

It had gone up for taxlean sale in 2009, but never sold.

It had sat empty since.

By 6:45 p.

m.

, Reyes was behind the wheel again, driving up the cracked dirt road, tires kicking dust into the fading gold of evening.

The Ames property emerged at the top of a shallow ridge, a crumbling barn, a rusted out pickup, and a two-story farmhouse, boarded windows, slanted porch, and ivy growing wild across the south wall.

She parked at the gate and approached slowly.

The door hung slightly open.

Inside, the house was dark, quiet, and cooler than expected.

Smelled of mildew and something faintly sweet, like rotted peaches.

She moved carefully, flashlight cutting swaths through the still air.

Then she saw it, a Polaroid taped to the wall above the fireplace.

It showed James Hartwell, older, bearded, shirtless, eyes glassy.

He was standing in the round chamber under the blue house, but the timestamp was handwritten on the white frame.

April 2006, nearly 9 months after the Hartwells vanished.

James had lived almost a year in captivity.

Reyes moved deeper into the house.

Upstairs, a room had been converted into what looked like a surveillance post.

Decades old wires from defunct monitors.

A dusty realtore recorder.

On the shelf, dozens of tapes.

She pulled the one marked JH13 slided into the deck.

The tape hissed.

Then, “What’s your name?” A long silence, then a weak voice.

James.

James Hartwell.

Do you remember why you’re here? Pause.

You said You said I couldn’t leave yet.

Because because I’m still broken.

Reyes’s hand trembled.

A second voice answered him, soft, distant, barely audible.

No, not broken.

Becoming.

She took every tape, every photo, every scrap of paper.

Back at the department, she locked herself in the interview room and laid everything out under the table lamp.

James hadn’t just been held.

He’d been conditioned, coerced, broken down, and rebuilt under the control of someone far more calculated than Granger.

The tapes continued, weeks of them.

James speaking in monotone, repeating phrases, echoing his captor’s language.

Then on the final tape, he says, “I’m ready now.

” Says, “I can see him clearly.

He says, I’m not the guest anymore.

I’m the host.

” Reyes closed her eyes and let the weight of it settle.

If James had survived that long, if he’d become what they’d made him, was he still out there? And worse, was he still playing the game? There were no remains, no conclusive proof of death, no body, just whispers and one final phrase scratched in the margin of the last tape box.

Mile marker 12 is where I ended.

But the new place is where I began.

July 29th, 2023.

Location: San Louis Obyspo County Sheriff’s Department.

Evidence review room.

The audio from the final tape echoed in Reyes’s head long after the reel stopped spinning.

Mile marker 12 is where I ended, but the new place is where I began.

She stared at the words again, scratched not in ink, but with something sharper, etched deep into the cardboard lining of the tape box.

The handwriting wasn’t the captors anymore.

It was James’.

He’d left them a breadcrumb trail.

Reyes opened a county parcel map and began tracing each location mentioned in the journals, tapes, and old Granger contracts.

She highlighted the blue house, the buried coffin, the equipment yard, the farmhouse.

They formed a triangle.

But it wasn’t until she overlaid an old utilities map drawn before the wildfire rroots of 1992 that she noticed something else.

A private parcel of land nestled in the center of the triangle, listed only as parcel 343, unincorporated.

It had no listed structure, no driveway, and no utility hookups.

But there was one road, an overgrown trail off the Pacific Coast Highway, ending at a gated dirt path marked only by a rusted sign.

Trespassers will be prosecuted.

And just beneath that, barely visible beneath lyken and rust, Reyes spotted it.

MM12.

1.

By midafter afternoon, she was standing in front of it.

The gate wasn’t locked, just rusted shut from decades of disuse.

She pushed until the hinges snapped and walked in.

The trail curved through overgrown eucalyptus trees and dense brush, the seab breeze carrying faint salt and decay.

30 yards in, the path dipped, and she saw it.

A bunker, concrete, sloped roof, no windows, almost invisible from above, the kind of place built to disappear.

There were bootprints in the dirt.

Recent.

Someone else had been here.

She unholstered her weapon.

The door was reinforced steel, sealed, but not locked.

Inside, darkness, thick, absolute.

She clicked on her flashlight and stepped down into the cold.

The air was different, stale, but stirred, as if it had been breathed in and out.

Recently, the corridor was narrow, walls lined with insulation foam, the floor still damp from the last rain.

She moved cautiously, handbrushing the wall.

And then the hallway opened into a large room.

Concrete walls, two mattresses on the floor, a folding table covered in journals, tape decks, and polaroids.

Dozens of them, all of James, in various stages, shaven, bearded, clean, filthy, standing, sitting, smiling.

And in the final photo taken just outside the bunker, he was alone, holding a map, staring straight at the camera.

Reyes stepped deeper into the chamber, her light catching the edges of another doorway.

This one wasn’t open.

It had been bricked over, but the cement was new.

She ran her hand over it and felt heat still radiating from within.

Someone had sealed this off within the past week.

She marked it for demolition and backed out.

As she turned to leave, her beam caught one final object on the floor near the wall.

A wedding ring tarnished inside the band.

J plus E.

always James Hartwell’s ring still warm.

That night, Reyes filed an emergency order for ground excavation and structure demolition on parcel 343.

The sheriff pushed back.

So did the county, but she didn’t wait.

By 3:00 a.

m.

, she was back at the bunker with a private demolition contractor.

2 hours later, the bricked up door collapsed.

Behind it was a narrow room, 8 by6, no light source.

In the center of the floor was a shallow pit lined with stone.

Inside there were bones, human.

Dozens of them, not fresh, not recent.

Some small, some adult-sized, arranged in a spiral.

A crude altar stood nearby, stained dark along the wall, scrolled in ash and blood.

The house isn’t where we lived.

The house is what we became.

Reyes couldn’t breathe.

This wasn’t just captivity.

This was ritual.

This was transformation.

She stepped back, staring at the spiral, and realized something else.

This wasn’t only about James and Emily.

There were more victims, more rooms, more chapters, and someone, maybe Granger.

July 30th, 2023.

Location, San Louis, Obyspo County, bunker site, parcel 343.

The bones were tagged and bagged by sunrise.

17 individual sets, according to the preliminary forensics count.

Reyes stood over the excavation site, still staring into the spiral that had once been a shallow grave.

It didn’t look like a dumping ground.

It looked like a ritual.

Each set of remains was curled into a fetal position, arms wrapped inward as if arranged that way postmortem.

Some of the skulls had been painted, smeared with soot or what might have been blood, though lab confirmation was still pending.

This went far beyond the heart wells.

Granger was dead, but someone else, perhaps multiple people, had continued the cycle, and someone had sealed the chamber very recently.

Midm morning, Reyes received a call from the lab.

They’d run mitochondrial DNA on the smallest of the bone sets, a child likely no older than seven.

The match came back in less than an hour.

Missing person file MC981 Ashley Weaver, age six.

Reported missing September 2006.

Over the next hour, five other sets returned hits from cold cases spanning 2004 to 2011.

The victims weren’t random.

They had vanished near the same Pacific corridor.

Different towns, different years, but all along the same stretch of forgotten road near mile marker 12.

Back at the office, Reyes pinned the names and photos to the evidence board.

A line began to form threaded in red yarn and ink.

Emily Hartwell 2005 Ashley Weaver 2006 Daniel Keats 2007 Felicia Monroe 2009 Troy Beck 2011 and then a gap.

No confirmed disappearances tied to the pattern after 2011.

Why had the killer stopped, gone dormant? Or had they become something harder to trace? She turned back to the tape transcripts.

James’s voice echoed in her ears.

I’m not the guest anymore.

I’m the host.

What if the ritual had worked? What if it had transformed him into someone else? That evening, Reyes reviewed the surveillance logs from the trail camera near parcel 343.

The camera had only been installed 2 weeks earlier, but it had caught something.

3 days ago, just before Reyes first found the bunker, someone had walked out of it.

A man, early 30s, thin, bearded, wearing a hooded jacket and hiking boots, carrying a duffel.

The time stamp 4:03 a.

m.

The man paused at the trail head, looked directly into the camera, then walked east toward the coast.

Reyes froze the frame.

She enhanced it, adjusted the lighting.

The man’s face was older, worn, but familiar.

James Hartwell, still alive.

That night, Reyes drove alone to mile marker 12.

She parked just beyond the turnoff, where the road sloped toward the bluff.

Fog hung low again, just like the night the Hartwells vanished.

She sat on the hood of her car and waited, staring out at the sea, thinking James hadn’t died in the chamber.

He hadn’t escaped and vanished.

He’d become the chamber or what it meant.

Not just the victim, not even the survivor.

something else.

She thought of his voice on the tape.

He said the longer I stayed, the less I’d want to leave.

Maybe James hadn’t left.

Maybe he’d changed into what she didn’t know yet.

But if he was out there, he was moving again.

And he wasn’t done.

By midnight, Reyes returned to her office.

On her desk was a package.

No return address.

inside a flash drive labeled final tape.

She plugged it into her laptop, hands trembling.

The screen went black for a long moment.

Then a static shot of a room, stone walls, low ceiling, candle light flickering.

James Hartwell stood in the center, arms by his sides, still quiet.

He looked directly into the camera and spoke.

This is the last room, but not for me.

I built it for you.

The camera zoomed slightly.

Not mechanically.

Someone was filming.

James continued.

You followed long enough.

You deserve to see what’s underneath.

The house was only ever a door.

He smiled.

And you’re already inside.

Reyes’s monitor went black.

She sat in the dark, every light in the station suddenly flickering.

Her phone buzzed once.

Unknown number, no message, just an image.

A photo of Reyes standing outside the blue house.

Taken from behind.

July 31st, 2023.

Location, Reyes’s apartment, Mororrow Bay, California.

She barely slept.

The photo haunted her.

The angle, the timing, the implication.

Someone had been watching her, standing no more than 15 feet away, and she hadn’t sensed a thing.

By morning, Reyes had forwarded the image to forensics, but the metadata had been wiped.

No GPS, no timestamp, no device ID, just static when they enhanced the image edges.

Whoever sent it knew what they were doing, and they wanted her to know she’d been seen.

Later that morning, Reyes drove north, retracing the path from the bunker to the sea, then up the winding roads toward the remote bluff roads between Cambria and San Simeon.

James Hartwell wasn’t hiding in the shadows anymore.

He was leading her.

She stopped just before mile marker 12.

1 and walked the rest of the way.

The fog had thinned, sunlight slanting over the cliffs, baking the rocks in morning heat.

And there, off the side of the highway, was something new.

A trail, fresh, trampled grass, broken branches.

She followed it without hesitation.

It wound for nearly half a mile before revealing what felt like an illusion.

A small cabin, wood siding, tin roof, porch with a single rocking chair, no windows on the sides, no visible power.

Reyes approached carefully.

No one answered when she knocked.

She tried the handle.

It opened.

The inside was empty.

No furniture, no photos, no dishes or clothes, just walls covered in writing, not painted.

Scratched hundreds of overlapping phrases etched deep into the wood, ceiling to floor.

She stepped closer and began to read.

I am what he made.

The house is where I disappeared.

The walls listen.

Emily was the last thing I loved.

I stayed until I became the lock.

And then across the entire back wall in bold carved letters.

Every door is a decision.

In the corner sat an old realtore player, plugged in, loaded.

Reyes pressed play.

James’s voice returned.

Older, slower, worn.

By now, I’m not sure what I am.

The rooms changed me.

Each one erased a piece.

Emily didn’t survive the process, but I did.

A pause, breathing, the sound of wind in the background.

I was given a choice, you see.

Leave or stay and become.

I chose to stay because I thought it was power.

But it was never power.

It was a pattern.

A long silence.

You came looking for the man who vanished.

But you found the one who replaced him.

Then this is the last room.

The tape stopped behind the player.

The floor creaked.

Reyes knelt and ran her hand across the boards.

There a seam.

She pulled until a section of floor lifted revealing a hidden compartment.

Inside a box, black lacquered wood, metal clasp.

She opened it.

Inside were photos.

Dozens, victims, trophies, captures, Emily, Ashley, others, so many others.

And at the very bottom, one final Polaroid.

A photo of Reyes taken at a gas station yesterday.

On the back, scrolled in pencil.

One more room.

If you want the truth, open it.

Underneath the photo was a small key stamped into its base.

Mm13.

That evening, Reyes stood at the edge of the Pacific.

beyond where the last paved roads ended.

There was no official mile marker 13.

The road split before then, but old surveyor records from the 1970s marked a coastal maintenance shed labeled MM13, a structure long since abandoned after the cliffs eroded.

Reyes hiked the last stretch alone.

Flashlight in one hand, the key in her pocket.

She found the shed by moonlight, barely standing, covered in ivy.

Leaning into the seab breeze like it was ready to fall, she pushed the door open.

Inside, stairs led down, stone, damp, wreking of salt and rot.

She descended, each step echoing louder than the last.

At the bottom, a steel door.

The key fit.

It clicked.

The door opened, and beyond it, darkness, but not empty.

The sound of breathing.

Then a voice, “Welcome home.

” August 6th, 2023.

Location unknown.

The emergency call came at 4:12 a.

m.

A private hiker had found an unmarked patrol vehicle abandoned near a collapsed maintenance shed along the northern cliffs past San Simeon.

Engine still warm, driver’s door open, no sign of struggle.

Inside, a flashlight, a holstered service weapon, Detective Eva Reyes’s badge, and nothing else.

The shed itself had given way during a rock slide overnight, half buried in coastal debris.

Search teams combed the ruins for 3 days.

K9 units, drones, thermal scans, nobody, no footprints, no trace.

Reyes had vanished, just like the others.

One week later, an envelope arrived at the St.

Louis Abyispo Sheriff’s Department.

No return address.

Inside, a single Polaroid.

Taken in dim light.

It showed a concrete room, stone walls, low ceiling, candle lit shadows curling against the walls.

In the center sat a chair, and in that chair, Reyes, alive, eyes open, staring directly into the lens, expression unreadable.

behind her on the wall, faintly visible.

This time she stayed.

6 months later, podcast into the dark.

Episode 93.

Mile marker 12.

The road that took them all.

They say the Pacific Highway is haunted.

That something rides the fog like a whisper, waiting for the right kind of mind to break open.

First it was the heart wells, then the missing children.

Now Detective Eva Reyes.

And no one ever finds a body, just silence and rooms.

Unmarked rest stop.

Pacific Coast Highway.

117 a.

m.

A blue sedan pulls over quietly in the fog.

A man steps out.

Middle-aged, clean shaven, calm.

He stands at the edge of the cliff, looking out at the black water, then turns back toward the highway.

He’s holding a worn photo in his hand.

The wind picks up.

He smiles, small, knowing, and begins walking down a footpath marked only with a small wooden post.

Mm 12.

1.

As the fog swallows him whole, the camera clicks once, unseen, then again, then silence.

News

🐘 Lawmakers Erupt: Mamdani’s Deceitful Campaign Promises Under Fire! 💣 “Trust is the currency of politics, and Mamdani is bankrupt!” In a dramatic clash, lawmakers have slammed Mamdani for betraying the trust of New Yorkers with his hollow promises. As the investigation unfolds, the community is left in shock—what does this mean for the future of leadership in the city? With public confidence at an all-time low, the pressure is on Mamdani to make amends or face the consequences of his actions. The clock is ticking! 👇

The Reckoning: Zohran Mamdani’s Broken Promises and the Fallout In the heart of New York City, a storm is brewing…

🐘 Major Breakthrough: Range Rover Linked to Nancy Guthrie Case Investigation! 🕵️♀️ “The truth is often stranger than fiction!” In an unexpected turn of events, police are now investigating a Range Rover in connection with the high-profile Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, new leads are emerging that could change everything we thought we knew. What role does this vehicle play in the unfolding drama? The public is on high alert, and the quest for justice has never been more urgent! 👇

The Dark Turn in the Nancy Guthrie Case: A Range Rover and a Web of Secrets In the unfolding drama…

🐘 The Truth Behind the Curtain: Dark Secrets of the Rich and Famous Revealed! 🕵️♂️ “Behind every glamorous facade lies a hidden truth!” In an exclusive exposé, we dive deep into the dark underbelly of celebrity life, where nothing is as it seems. As shocking secrets and scandals come to light, the glittering world of fame is exposed for the charade it truly is. Who will emerge unscathed, and who will be left in ruins? With every revelation, the stakes get higher, and the drama intensifies, proving that in Hollywood, the truth is often stranger than fiction! 👇

The Heart-Wrenching Truth: Nancy Guthrie’s Daughter Breaks Her Silence In a world where the bright lights of Hollywood often mask…

🐘 THRILLING FIGHT RECAP: Terence Crawford vs. Canelo Alvarez—Highlights You Can’t Miss! 💣 “In the ring, anything can happen!” Experience the heart-pounding moments from the showdown between Terence Crawford and Canelo Alvarez, where every punch counted and every round was a battle! What were the turning points in this high-stakes fight, and how did both champions prove their mettle? Dive into the highlights that captured the essence of this monumental boxing event! 👇

Chaos in the Spotlight: Lil Baby’s Arrest Shakes the Entertainment World In the glittering world of fame and fortune, where…

🐘 EPIC ENCOUNTER: Terence Crawford vs. Canelo Alvarez—Boxing Highlights That Left Fans Breathless! 🌪️ “Two warriors, one destiny—who claimed the crown?” Relive the unforgettable highlights from the fierce encounter between Terence Crawford and Canelo Alvarez, where both fighters showcased their incredible talent and determination! What moments defined this epic clash, and how did the crowd react to the intensity in the ring? Don’t miss the highlights that made this fight a landmark event in boxing history! 👇

Clash of Titans: The Epic Showdown Between Canelo Alvarez and Terence Crawford In the electrifying world of boxing, where legends…

🐘 Jose Aldo’s TRAGIC Fate: The Untold Story Behind the Legend’s Downfall! 💣 “When the spotlight fades, the struggle begins.” In a shocking exposé, the tragic fate of Jose Aldo reveals the hidden battles faced by the former champion after his fall from grace. What events led to this unexpected decline, and how does it reflect the harsh realities of professional sports? As fans grapple with the implications of his journey, the story of Aldo serves as both a cautionary tale and an inspiration! 👇

The Rise and Fall of a Champion: The Tragic Fate of José Aldo In the world of mixed martial arts,…

End of content

No more pages to load