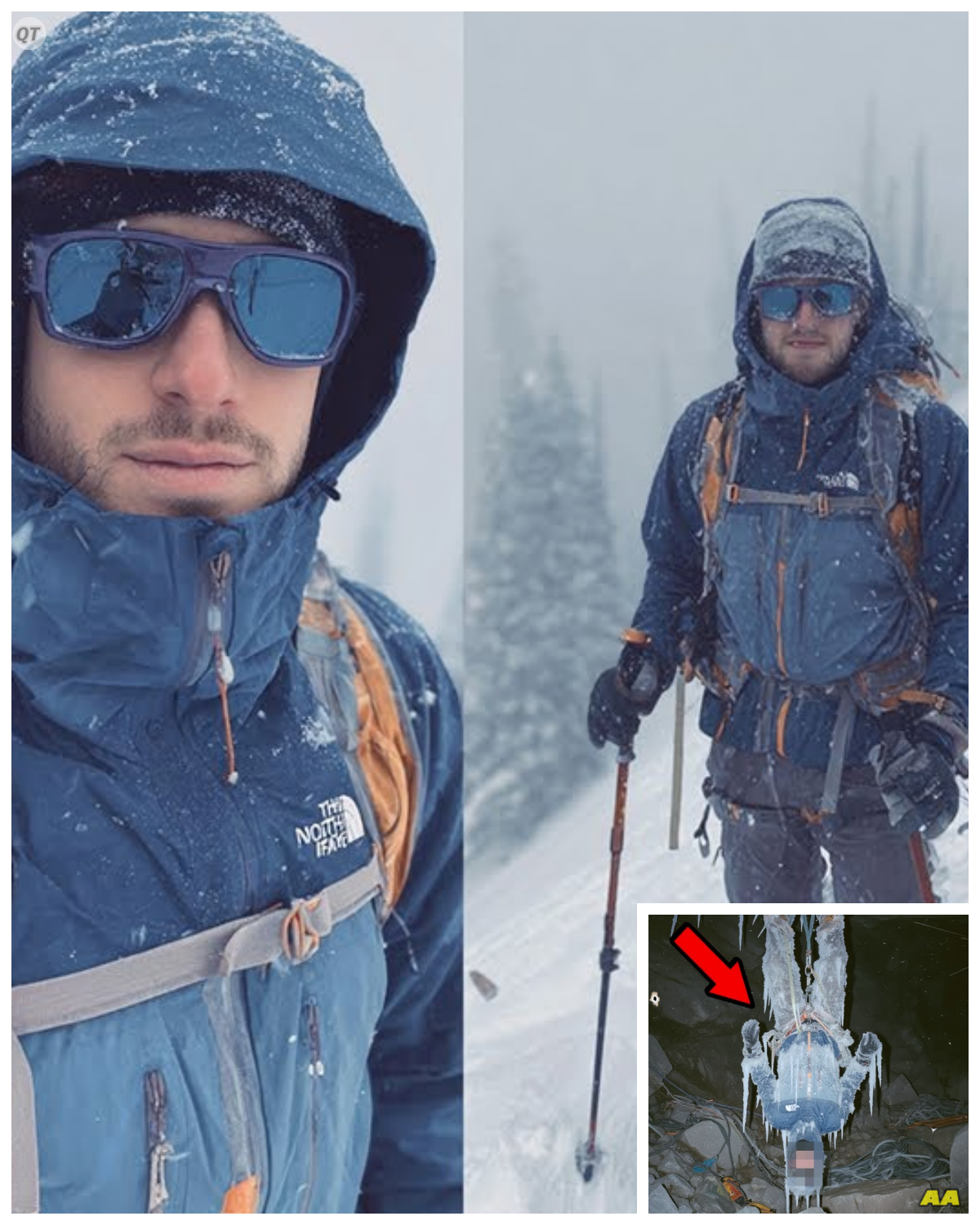

When rescuers found the body, it was hanging upside down in the ice, frozen, covered in ice, tied with a climbing rope to the cave wall.

The man had been dead for 2 years, and someone had deliberately hidden him there.

Summer 2005, Denali National Park, Alaska.

The highest mountain in North America, 6,190 m above sea level.

A harsh, dangerous place.

The weather changes in minutes.

The temperature can drop to minus40 even in summer.

Glaciers, creasses, avalanches.

Every year, people die here.

Scott Mcandalas flew to Alaska in early June.

He was 41 years old, lived in Colorado, and owned a small construction company.

He had been climbing for about 10 years.

Not a professional, but experienced.

He had climbed several peaks in the Rocky Mountains and had been to Reineer in Washington State.

Denali was to be his most serious climb.

He had been preparing for several months.

He trained physically, gathered equipment, and studied roots.

Denali is not a mountain for beginners.

It requires a climatization, the right equipment, and experience.

Scott understood the risks.

He decided not to go alone.

He hired a guide through a company in Anchorage that specialized in mountain expeditions.

The company was called Alaska Summit Guides.

It had been around for about 15 years, was licensed, and had good reviews.

They provided guides for climbs on Denali and other peaks in the region.

When Scott contacted them, they offered him an experienced sherpa, Pembbea Lakpa.

Pemba was from Nepal and was 32 years old.

He had been working as a guide for about 12 years.

He started on Everest, then moved to the United States, obtained a work visa, and found employment with several mountaineering agencies.

He had certificates and recommendations.

On paper, he looked like a reliable professional.

They met in Anchorage a week before the climb.

They discussed the route, timing, and conditions.

Pemba explained that the ascent would take about 2 weeks.

The standard route was through the Cahiltina Glacier, setting up several camps at different altitudes for acclimatization than storming the summit.

The weather in June is usually more stable, but there are no guarantees.

Scott paid the full cost of the services in advance, $8,000.

This included the guide services, some of the equipment, and logistics.

The contract was standard, signed by both parties.

There were no unusual conditions.

On June 14th, 2005, they flew in a small plane to the Cahilna Glacier.

This is where Denali base camp is located, the place where most climbs begin.

It is at an altitude of about 2,000 m.

The weather was good.

Visibility was excellent.

There were several other groups at base camp, climbers from different countries, guides, pilots.

Scott and Pembbea registered in the climbing log book and obtained permission from the National Park Rangers.

They spent two days at base camp checking their equipment and preparing for the ascent.

On June 16th, they began their ascent.

The plan was standard.

Climb gradually, set up camps at an altitude of 3,000 m, then 4,000, then higher.

Alimatization is critically important.

If you climb too fast, altitude sickness sets in.

Headaches, nausea, pulmonary or cerebral edema.

It can kill you in a matter of hours.

The first few days went smoothly.

They moved slowly, carrying heavy backpacks.

The weather held.

Scott felt good and acclimatization was going well.

Every evening they contacted base camp by radio, reporting their location and condition.

On June 20th, they set up camp at an altitude of about 3,800 meters.

Scott wrote in his diary that he was tired, but overall everything was going according to plan.

The weather began to deteriorate, the wind picked up, and the temperature dropped.

Pembbe said they needed to wait a day or two for the weather to improve.

On June 21st, Scott made his last entry in his diary.

He wrote that Pembbea was demanding additional payment, $5,000 in cash right now.

He threatened to go back down without him if he didn’t get the money.

Scott wrote that this was absurd, that he had already paid the full amount under the contract.

He didn’t understand why Pemba was doing this now, halfway through the route.

On the same day, Scott contacted Base Camp by radio.

The conversation was recorded, standard procedure for all Denali ascents.

In the recording, Scott can be heard telling the operator that he has a problem with his guide, that Pemba is demanding additional money and threatening to leave.

The operator advises them to descend together and resolve the issue at base camp.

Scott replies that he will try to talk to Pembbea and hopes to settle the situation.

This was the last contact with Scott.

On June 22nd, Pemba made contact alone.

He reported that Scott was missing.

According to him, Scott left the tent at night to go to the toilet and did not return.

Pembbea searched for him for several hours, shouting and shining a flashlight.

He found no traces.

He assumed that Scott might have fallen into a creasse.

There are many of them on this section of the route, some hidden by snow.

The base camp operator immediately contacted the National Park Rescue Service.

Within a few hours, a search and rescue operation was organized.

The helicopter could not take off due to bad weather, so the ground team began the ascent on foot.

On June 23rd, rescuers reached the camp where Pemba was staying.

He looked tired and said he had hardly slept, continuing to search for Scott.

He showed them the place where, in his opinion, Scott had left during the night.

Rescuers began their search.

They combed the area within a radius of several hundred meters around the camp.

They checked all visible creasses, slopes, and possible roots.

They looked for tracks in the snow, pieces of clothing, and equipment.

They found nothing.

The weather was deteriorating, visibility was falling, and a blizzard was beginning.

On June 24th, the search continued.

Several more rescuers and volunteers from other mountaineering groups on the mountain joined the team.

They expanded the search area and checked all known dangerous areas.

One of the rescuers descended into several large creasses on ropes.

Nothing.

On June 25th, the weather became critical.

There was a storm.

Visibility was almost zero.

The temperature was -35° C and the wind was over 100 kmh.

It was impossible and dangerous for the rescuers themselves to continue the search.

The head of the operation decided to evacuate everyone down the mountain.

Pembbea descended with the rescuers.

At base camp, he was questioned in more detail.

He repeated his story.

Scott had gone out at night, had not returned, and had most likely fallen into a creasse.

The rescuers asked about the conflict over money.

Pembbea said it was a misunderstanding that they had discussed the possibility of additional services, but there had been no serious conflict.

The rangers checked his equipment.

Everything was in order.

Ropes, carabiners, iceaxs, krampons, the standard set.

Nothing suspicious.

They recorded his statement, photographed his equipment for the report, and let him go.

Scott’s family was notified of his disappearance.

His wife flew to Alaska 2 days later.

She met with the rangers and representatives of Alaska Summit Guides.

Everyone expressed their condolences and said they had done everything possible.

They explained that people go missing on Denali every year.

Cracks, avalanches, falls, these are part of the risk.

Scott’s wife demanded that the search continue.

The rangers explained that they would continue as soon as the weather improved, but the chances of finding him alive were practically zero.

If he had fallen into a deep creasse, it might be impossible to recover his body.

In early July, the weather stabilized.

A second search operation was organized.

A helicopter flew over the area of his presumed disappearance.

Rescuers retraced his route and checked all accessible locations.

The result was the same.

No traces.

The case was transferred to the Matanuska Susitna County Sheriff’s Office, which had jurisdiction over Denali National Park.

The detective studied all the materials, questioned Pembbea again, and checked his background.

No criminal history was found.

Scott’s finances were checked.

No oddities, debts, or conflicts.

The detective also listened to the recording of the radio communications on June 21st where Scott complained about Pembbea’s demands.

It was suspicious, but it didn’t prove anything specific.

Conflicts between clients and guides happen.

They don’t always end in murder.

Pembbe was called in for further questioning.

He was asked for more details about the money.

He explained that Scott wanted to change the route to climb higher than planned, which required additional time and effort.

Pembbe said he asked for compensation for the extra work.

Scott refused.

They argued, but then agreed to continue with the original plan.

No threats, no violence.

The detective checked the contract between Scott and the company.

It did indeed include a clause about the possibility of changing the route for an additional fee.

Formally, Pembbea had the right to ask for extra payment if the client changed the terms, but there were nuances.

First, the radio communication recording did not confirm Pembbea’s version.

Scott said that Pemba was demanding money and threatening to leave, but did not mention a change in route.

Second, in Scott’s diary, which was in his tent and which Pemba gave to the rescuers, the last entry also described the demand for money as unreasonable.

But that was still not enough for an indictment.

No body, no direct evidence of a crime.

Technically, it is possible that Scott did indeed go out at night and fell into a creasse.

This happens on Denali.

In August 2005, the case was closed as an accident.

The official conclusion was that Scott McCandless presumably died as a result of falling into a creasse.

The body was not found.

The search was called off.

Scott’s family did not agree with his conclusion.

They hired a private investigator who re-examined the case.

He interviewed other climbers who were on the mountain at the time, checked Pembbea’s reputation, and contacted his previous clients.

He found several people who complained about Pembbea’s aggressive behavior and demands for additional money, but there was no evidence of a crime.

The private investigator also checked Pembbea’s finances.

He discovered that he had debts about $15,000 in credit card bills and overdue payments.

This could have been a motive for demanding money from Scott, but again, it did not prove murder.

The detective wrote a report and sent it to the family and the sheriff’s office.

The sheriff promised to keep the case open and continue to follow up on any new information.

But in reality, he did nothing.

The case was filed away.

A year passed.

Scott’s family held a private memorial service.

No body, no funeral.

Just family and friends gathered to remember Scott.

His wife gradually tried to move on, although she did not believe it was an accident.

She was sure that Pembbea had done something to her husband.

Pembbea continued to work as a guide.

Alaska Summit guides did not fire him.

Officially, he was not at fault.

Accidents are an occupational hazard.

He guided other clients on Denali and other mountains.

Life went on.

Another year passed.

The summer of 2007.

A group of professional speliologists and climbers from Canada arrived at Denali.

They specialized in exploring ice caves, rare natural formations inside glaciers.

Such caves are formed by meltwater, creating complex systems of tunnels and cavities inside the ice.

The group consisted of five people.

The leader was David Porter, 46 years old, an experienced caver and climber.

His team had explored caves in Canada, Alaska, and Iceland.

They had special equipment, probes, radars, cameras, and lighting.

They chose a site on the southern slope of Denali at an altitude of about 3,900 m.

According to geological studies, there should have been a vertical ice cavity there, a rare type of cave that goes deep into the glacier.

On July 23rd, 2007, they found the entrance to the cave.

It was a small hole in the glacier, partially hidden by snow.

David and two other team members descended inside on ropes.

The cave was impressive.

A vertical shaft descended about 30 m, then widened into a large cavity.

Walls of blue ice, stelactites, complex formations.

The team began to photograph, measure, and document.

When they descended to the bottom of the cavity, one of them pointed a flashlight at the far wall and froze.

A human body was frozen into the wall, upside down, head down, legs tied with a climbing rope to hooks driven into the ice.

The body was completely frozen, covered with a layer of ice.

But the clothes, equipment, backpack, everything was visible.

David moved closer.

The body was mummified by the cold.

The skin was dark and dry, but the facial features were distinguishable.

A middle-aged man.

He was wearing a climbing jacket, pants, boots, and a helmet.

His arms were stretched down toward his head as if he had been trying to reach for something before he died.

The team immediately contacted base camp.

They reported the discovery.

They asked to contact the National Park Rangers and the police.

The rangers arrived the next day.

They were accompanied by a medical examiner and two detectives from the sheriff’s office.

The climb to the cave took several hours.

The weather was stable, but working at such an altitude is always difficult.

Every movement requires effort, and there is not enough air.

They descended into the cave with David’s team.

They set up additional lighting and examined the body.

The medical expert confirmed that the man was dead and had been there for a long time, at least a year, maybe more.

It was difficult to determine the exact time of death in conditions of constant frost.

The body was indeed hanging upside down.

The rope was wrapped around the ankles several times, then tied to two ice hooks driven into the cave wall about 3 m above the floor.

The hooks were standard climbing hooks used for safety on difficult sections.

The detective examined the rope carefully.

The knots were professional and strong.

Someone knew what they were doing.

This was not an accidental death.

The person had been hung deliberately.

The medical examiner noticed another detail.

The body was covered with a layer of ice, but not evenly.

On the clothes, especially the jacket and pants, the ice was thicker, forming growths.

It was as if the body had been doused with water before being hung.

In the freezing conditions, the water froze quickly, creating an additional layer of ice.

Why was this done? The expert suggested that it was to speed up the freezing process, to make the body part of the ice wall, to hide it.

Someone tried to make sure that the corpse would remain here forever, become invisible.

The backpack was still hanging on the victim’s back.

The detective carefully unfassened it and took out the contents.

There were standard items, a thermos, spare gloves, a map, a compass, energy bars, and documents in a waterproof bag.

The detective opened the bag.

Inside were a passport, driver’s license, and insurance card.

The name was Scott McCandless.

The address was in Colorado.

The photo in the passport matched the face of the deceased as far as could be judged from the mummified features.

The detective immediately remembered the case.

Scott McCandless missing two years ago.

An accident, presumably a fall into a creasse.

Body not found.

Case closed.

But now the body was in front of them.

And it was definitely not an accident.

The man had been killed, dragged into the cave, hung up, and dowsed with water.

It was premeditated murder and concealment of a body.

The detective immediately contacted the sheriff’s office by satellite phone.

He reported the discovery, asked for the old Macandas case to be reopened, and requested an additional forensic team.

The body had to be removed and transported down for detailed examination.

This proved to be a difficult task.

The ice on and around the body had to be carefully melted so as not to damage the evidence.

The rope could not simply be cut.

It was evidence.

The team worked for several hours.

They used special heating tools to melt the ice around the hooks.

Finally, they were able to free the rope.

The body was carefully lowered to the floor of the cave and placed in a special transport bag.

While they were working with the body, the forensic scientist examined the cave.

He looked for other evidence, traces, objects, anything.

He found several interesting things on the floor of the cave.

The first was another rope lying separately, partially frozen into the ice.

It was shorter, about 5 m long, with one end cut off with a knife or tool.

The forensic investigator photographed it and packed it into a bag.

The second was a metal carabiner lying in the corner of the cave.

It was a standard mountaineering carabiner used to attach ropes.

It had signs of wear and scratches.

The forensic investigator also packed it up.

The third was stains on the cave floor.

They were dark and frozen.

It could have been blood, dirt, or something else.

The forensic scientists took ice samples from these stains for analysis.

It took 2 days to transport the body down.

We had to move slowly and carefully.

At an altitude of almost 4,000 m, any mistake could be fatal.

Fortunately, the weather held.

On July 26th, the body arrived at the morg in Anchorage.

A detailed examination and autopsy began.

Alaska’s chief medical examiner, Dr.

Robert Chen, personally took on the case.

The first thing he noted was the condition of the body.

The freezing occurred quickly, probably within a few hours after death.

This preserved the tissues in relatively good condition.

The internal organs were damaged by ice, but many details could be examined.

Dr.

Chen examined the head.

He found a trauma to the back of the head, a dent in the skull about 4 cm in diameter.

The bone was cracked, and there were signs of internal bleeding.

The injury was inflicted with a blunt object with great force.

It could have been a fall onto a rock or ice.

But Dr.

Chan had his doubts.

The shape of the injury was too smooth and rounded.

It looked more like a blow with an object, the handle of an ice axe, a rock in the hand, something like that.

There were also strange marks on the neck.

Vertical stripes as if from the pressure of a rope, but not horizontal as in strangulation, but vertical.

Dr.

Chen realized that this was because the body had been hanging upside down.

The rope around the ankles held the weight of the body, but an additional rope was wrapped around the chest and neck for support.

When the body was hanging, this rope pressed on the neck.

The hands were examined separately.

There were abrasions and scratches on the fingers, especially on the right hand.

The nails were broken.

It was as if the man had tried to grab something, scratching the surface.

Perhaps he was still alive when he was hung up, trying to free himself.

The thought was horrifying.

Imagine a person hanging upside down in an icy cave, slowly freezing to death, unable to free himself.

But Dr.

Chen could not say for sure whether Scott was conscious.

The head injury could have caused loss of consciousness or he could have died from it before he was hung.

Analysis of the stomach contents showed that the last meal was several hours before death.

standard hiking food, canned food, energy bars.

No signs of poisoning or unusual substances.

Dr.

Chen made a preliminary conclusion.

The cause of death was head trauma and hypothermia.

The injury was serious enough to be fatal, but death may not have been immediate.

Hypothermia accelerated the process.

The manner of death was murder.

At the same time, forensic scientists examined the physical evidence, the rope used to hang the body and a second rope found on the cave floor.

Also, a carabiner and samples of ice with stains.

The ropes were standard climbing ropes 10 mm in diameter, strong, designed for a load of up to 22 kilon newtons.

The first rope which held the legs showed signs of wear at the knots, but in addition, there was a small stamp on it.

The forensic scientist examined the stamp under a microscope.

It was the manufacturer’s logo and additional markings.

The logo of Northern Peak Equipment, a manufacturer of mountaineering equipment.

Below the logo was the batch serial number, NPR20543.

This was an important discovery.

Manufacturers mark rope batches for quality control and tracking purposes.

If it is possible to determine where this particular batch was delivered, it is possible to find out who purchased the rope.

The detective contacted Northern Peak Equipment.

He explained the situation and requested information about batch NPR 200543.

The company responded 2 days later.

This batch was manufactured in March 2005 and consisted of 200 ropes, each 50 m long.

The entire batch was sold to three distributors on the west coast of the United States.

One of the distributors was located in Anchorage.

The detective went there in person.

The store manager checked his records.

They received 70 ropes from this batch in April 2005.

They sold them during May and June.

Unfortunately, not all sales were recorded in detail.

Many customers paid in cash and did not leave their names.

But there were corporate customers who bought in bulk on account.

Among them was Alaska Summit Guides.

They bought 20 ropes from this batch on May 20th, 2005.

The detective immediately contacted Alaska Summit Guides.

He asked for a list of guides who had received equipment from this batch.

The company provided the records.

The ropes were distributed among eight guides for the summer season.

Among them was Pembbea Lakba.

He received three ropes on May 23rd, 2005.

This linked Pemba to the rope that Scott’s body was suspended from.

But more evidence was needed.

The rope could have been stolen, lost, or given to someone else.

Forensic scientists examined the rope further.

They took samples for DNA analysis.

Biological material was found on the knots and in places where the rope had come into contact with Scott’s body.

Skin particles, sweat, hair.

A DNA profile was compiled.

Most of the DNA belonged to Scott.

This was to be expected as his body had been hanging on this rope for 2 years.

But traces of another person’s DNA were also found.

Traces of DNA were also found on the carabiner that was found in the cave.

The detective pulled up the old Scott McCandless case from the archives.

There were records of Pembbea’s interrogations and his contact information, but there was no DNA sample from Pemba in the case file.

There was no reason to take one at the time.

The detective began looking for a way to obtain Pembbea’s DNA for comparison.

He found out that Pemba was still working in Anchorage, living in a small apartment in the suburbs.

A warrant was needed to take a DNA sample, but grounds were needed for the warrant.

The detective filed a petition with the court.

He presented evidence, a rope with the batch number marked on it, Alaska Summit Guide sales records, and records of the rope being issued to Pemba.

He also presented old case materials, a recording of radio communications in which Scott complained about demands for money, and Scott’s diary.

The judge reviewed the materials.

He found that there were sufficient grounds for suspicion.

He issued a warrant to take a DNA sample from Pembbea Lockpa and to search his home.

The detectives arrived at Pemba’s house on the morning of July 29th, 2007.

He was at home getting ready for work.

He opened the door, saw the detectives, and immediately tensed up.

He asked what was going on.

The detective explained that they were investigating the death of Scott McCandless, had found new evidence, and needed to take a DNA sample to rule him out.

Pembbe tried to object, saying that the case was closed, and that he had already told them everything two years ago.

The detective showed him the warrant.

Pember read it, paused, then agreed.

They took a swab from the inside of his cheek.

They also searched the apartment.

They looked for any traces of Scott, old equipment, notes, photographs.

In the closet, they found a box of mountaineering equipment, ropes, carabiners, iceaxes, hooks.

The detective asked permission to take the equipment for examination.

Pembbe tried to object again, saying that these were his work tools.

The detective reminded him of the warrant.

Pembbea pursed his lips and nodded.

Among the equipment, they found something interesting.

A harness, a piece of mountaineering equipment that is worn around the waist and legs to attach ropes.

On the inside of the harness, on a fabric tag, the initials PL were written in marker Pemba Lakpa.

But in addition, there were old stains on the harness itself.

Dark ingrained in the fabric.

The detective packed the harness separately and marked it for analysis.

Pemba’s DNA sample and equipment were sent to the lab.

The results came back a week later.

Pemba’s DNA matched the trace DNA found on the rope and carabiner from the cave.

The match was on 23 markers.

The probability of error was 1 in several billion.

The stains on the harness were also examined.

It was blood.

The blood type matched that of Scott McCandless.

DNA analysis confirmed that the blood belonged to Scott.

This was decisive evidence.

Pembbe had contact with the rope used to hang Scott.

Scott’s blood was on his harness.

He was the last person to see Scott alive.

He had a motive.

Money.

He lied about what happened.

On August 2nd, 2007, detectives obtained an arrest warrant for Pembbealakba on suspicion of murdering Scott Mccandless.

They came to his workplace.

He was leading a group of tourists on a short trek in the vicinity of Anchorage.

The detectives waited until the trek was over and approached him when the group dispersed.

Pembbeas saw them and tried to run away.

He ran about 20 m, but the detectives caught up with him, wrestled him to the ground, and handcuffed him.

They read him his rights.

Pima remained silent, staring at the ground.

He was taken to the police station and placed in a cell.

The first interrogation took place the next day.

The detective laid out all the evidence in front of him, photographs of the body from the cave, DNA analysis results, records of the rope, and the bloodstained binding.

Pembbe looked at it all, his face stony.

The detective asked him directly, “Did you kill Scott McCandless?” Pembbea did not answer.

He asked for a lawyer.

He was assigned a public defender.

The lawyer met with Pembbea and studied the case files.

He told Pembbea that the evidence was very strong and that his chances of a quiddle were minimal.

He advised him to cooperate with the investigation and plead guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence.

Pembbe refused.

He said he would not admit to anything, that it was all a setup, that the DNA could have been planted, that he did not kill Scott.

The investigation continued.

Detectives studied the chronology of events, trying to reconstruct what happened on the night of June 21st, 2005.

According to their version, it all started with a conflict over money.

Pemba demanded $5,000.

Scott refused.

They argued.

Scott contacted base camp by radio and complained.

This angered Pemba even more.

At night, possibly when Scott was asleep or had left the tent, Pemba struck him on the head.

He used something heavy, maybe an iceax, maybe a rock.

The blow was strong.

Scott fell, lost consciousness, or died immediately.

Pembbe realized what he had done.

Panic or cold calculation? It is not known.

He decided to hide the body so that it would never be found.

He remembered a cave he had seen on this part of the route a few days earlier.

He dragged Scott’s body to the cave.

The distance was about 200 m.

At such an altitude, with such a load, it was difficult but possible for an experienced climber.

He climbed down into the cave with the body.

He hammered hooks into the wall.

He tied a rope to Scott’s legs and hung him upside down.

Then he poured water from a thermos or melted snow over the body.

The water quickly froze, creating an extra layer of ice and hiding the body in the cave wall.

Why upside down? Detectives speculated that it was to make the blood flow to his head to make his death even more cruel if Scott was still alive, or simply because it was easier to tie him by his feet than by his chest or arms.

Pembbea returned to camp.

He removed all traces of a struggle, if there were any.

He gathered Scott’s belongings and put them in the tent as if everything was normal.

In the morning, he made contact and reported the disappearance.

The version was convincing.

All the evidence supported it.

But Pemba denied everything.

He said it was fantasy, that he had no motive to kill a client, that it would ruin his career.

The detective objected, saying that he had debts and needed money.

Pembbea replied that $5,000 would not solve his debt problem.

Why kill for that? It was a fair question.

The detective thought about it.

Maybe it wasn’t just about money.

Maybe there was a personal conflict, an insult, something that caused rage.

They checked Pembbea’s phone records for the period before the climb.

They found several calls to Nepal to his family.

They asked a translator to listen to these conversations if there were any recordings from the telecom operator.

There were no recordings, but the detective contacted Pembbea’s family in Nepal.

His brother agreed to talk.

He said that Pembbea had called in May 2005 complaining about life in America.

He said that clients were disrespectful, that they paid little, that he was tired.

He complained especially about one client, a wealthy American who treated him like a servant.

The brother did not remember the client’s name, but the dates matched.

Pembbea had complained a few weeks before the climb with Scott.

It was probably him.

Maybe money wasn’t the only motive.

Maybe Pembbea had been harboring resentment, felt humiliated.

The conflict over money was the last straw.

He snapped, hit Scott, killed him.

This explained the cruelty hanging the body upside down, pouring water on it.

It wasn’t just hiding the body.

It was revenge, humiliation, even after death.

At a preliminary hearing in September 2007, the judge found the evidence sufficient to refer the case to trial.

Pembbe Lakpa was formally charged with first-degree murder.

The trial began in March 2008.

The prosecutor presented all the evidence.

DNA on the rope and carabiner, Scott’s blood on Pima’s harness, the rope markings, the radio communication recording, and the medical experts testimony about the head injury and the deliberate nature of the body’s suspension.

Witnesses were also called.

The team of cavers who found the body, rangers who participated in the initial search, a representative of Alaska Summit Guides who confirmed that Pembbea had been issued with the equipment.

Pembbe’s brother testified via video link from Nepal about Pemba’s complaints about clients.

The defense tried to challenge the evidence.

The lawyer argued that the DNA could have gotten on the rope accidentally, that Pemba worked with Scott, so naturally his DNA was on the equipment, that the blood on the harness could have been from another incident, from a cut or injury while working.

But the prosecutor refuted these arguments.

The DNA was specifically on the rope used to hang the body, not on other equipment.

There was a large amount of blood on the harness, not from a minor cut.

And most importantly, Pembbea lied about what happened that night.

The jury deliberated for two days.

They returned with a verdict of guilty of firstdegree murder.

The judge handed down the sentence in May 2008.

25 years in prison without the possibility of parole.

Also, compensation to Scott’s family in the amount of $500,000.

Pembbea appealed.

The court of appeals rejected it in 2009.

All the evidence was deemed lawful.

The trial fair.

Scott’s family finally got answers.

His body was cremated according to his wishes and his ashes were scattered in the mountains of Colorado where he loved to spend time.

His wife told reporters that she was glad that justice had prevailed even though it would not bring her husband back.

The Scott McCandless case changed the rules for guides in Alaska.

Now, all guides undergo more thorough background checks, including criminal history and financial status.

Companies are required to check references and contact previous clients.

Reporting requirements during clims have also been tightened.

Guides must check in twice a day, reporting their exact location and the condition of their clients.

In the event of any incident, an investigation is immediately launched and all details are checked.

Pembbeal Lakba is serving his sentence in an Alaska state prison.

According to prison officials, he has not repented or admitted guilt.

He works in the prison library and has little contact with other inmates.

The cave where the body was found is now closed to visitors.

National park rangers have blocked the entrance and put up warning signs.

The place has become a grim attraction that climbers talk about, but no one wants to go down

News

🐘 Nike’s Shocking Choice: Alex Eala’s $45 Million Contract Leaves Sabalenka in the Shadows! 🌪️ “One moment in the spotlight can change everything!” In an unexpected twist, Nike has announced a groundbreaking $45 million contract for tennis prodigy Alex Eala, effectively sidelining Aryna Sabalenka. As the tennis world buzzes with speculation, the implications for both athletes are immense. Can Sabalenka reclaim her position, or will this snub redefine her career? The drama unfolds as the competition heats up! 👇

The Shocking Snub: Nike’s $45 Million Contract for Alex Eala Leaves Aryna Sabalenka Reeling In a dramatic turn of events…

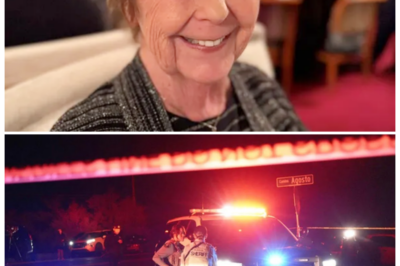

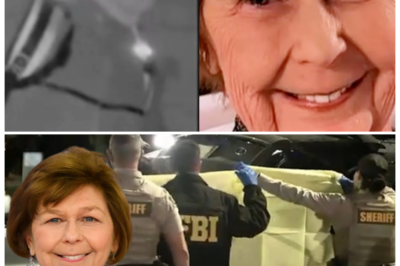

🐘 Revenge Motive Explored: Forensic Expert Raises Alarming Questions in Guthrie Case! ⚡ “The past has a way of catching up with us, especially in matters of revenge!” A renowned forensic expert has put forth a chilling theory that revenge may be a key motive in the ongoing investigation of Nancy Guthrie’s case. As the implications of this theory unfold, the community is left to ponder the relationships and rivalries that could have led to such a drastic act. Will this insight lead to the breakthrough everyone has been waiting for, or will it deepen the mystery? 👇

The Dark Motive: Revenge Uncovered in the Nancy Guthrie Case In a shocking revelation that feels like the climax of…

🐘 Emergency Alert: Boeing’s Departure from Chicago Sends Illinois Into a Frenzy! 💣 “Sometimes, the sky isn’t the limit—it’s the beginning of a downfall!” In an unprecedented move, Boeing has announced it will shut down its Chicago operations, leaving the Illinois governor scrambling to manage the fallout. As uncertainty looms over thousands of jobs and the local economy, the political ramifications are vast. Can the governor stabilize the situation, or is this just the beginning of a much larger crisis? The clock is ticking! 👇

The Boeing Exodus: Illinois Governor Faces Crisis as Jobs Fly Away In a shocking turn of events that has sent…

🐘 Nancy Guthrie Case Takes a Dramatic Turn: New Range Rover Evidence Discovered! 🌪️ “Sometimes, the truth rides in style!” In a shocking turn of events, authorities have unearthed new evidence related to a Range Rover that could change everything in the Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, questions abound: what does this mean for the timeline of events? With emotions running high and the community demanding answers, the stakes have never been greater. Will this lead to a breakthrough, or is it just another twist in a long and winding road? 👇

The Shocking Revelation: New Evidence in the Nancy Guthrie Case Changes Everything In a gripping twist that feels ripped from…

🐘 Lawmakers Erupt: Mamdani’s Deceitful Campaign Promises Under Fire! 💣 “Trust is the currency of politics, and Mamdani is bankrupt!” In a dramatic clash, lawmakers have slammed Mamdani for betraying the trust of New Yorkers with his hollow promises. As the investigation unfolds, the community is left in shock—what does this mean for the future of leadership in the city? With public confidence at an all-time low, the pressure is on Mamdani to make amends or face the consequences of his actions. The clock is ticking! 👇

The Reckoning: Zohran Mamdani’s Broken Promises and the Fallout In the heart of New York City, a storm is brewing…

🐘 Major Breakthrough: Range Rover Linked to Nancy Guthrie Case Investigation! 🕵️♀️ “The truth is often stranger than fiction!” In an unexpected turn of events, police are now investigating a Range Rover in connection with the high-profile Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, new leads are emerging that could change everything we thought we knew. What role does this vehicle play in the unfolding drama? The public is on high alert, and the quest for justice has never been more urgent! 👇

The Dark Turn in the Nancy Guthrie Case: A Range Rover and a Web of Secrets In the unfolding drama…

End of content

No more pages to load