Texas, 1945.

A messaul door swung open, and 12 German women stood at the threshold, staring at tables piled with food they hadn’t seen in years.

Real butter, white bread, mountains of hamburgers still warm from the grill.

One woman, barely 20, named Greta, whispered in broken English to the American sergeant, “Can we have leftovers?” He looked at her, confused, then laughed.

Not cruel, but surprised.

Leftovers.

Ma’am, this is all for you.

She didn’t believe him.

None of them did.

They had been told Americans were wasteful, cruel enemies.

The propaganda had prepared them for starvation.

Instead, they found abundance.

The train had carried them for 3 days across an ocean of land.

Through the small windows of the P cars, the women watched America unfold endless fields, towns untouched by bombs, children waving from farmhouse porches.

Greta pressed her forehead against the glass, feeling the vibration of the rails beneath her.

In Germany, every city she knew had been reduced to rubble.

Here, church steeples rose intact against blue sky.

The heat hit them first when they stepped onto the platform at Fort Sam Houston.

Texas heat, thick and still, wrapping around their wool uniforms like a second skin.

Dust hung in the air, catching the late afternoon light.

An American officer, young, maybe 25, gestured them toward waiting trucks.

His face showed neither hatred nor pity, just professional distance.

Welcome to Texas,” he said in careful German.

“You’ll be processed.

Assigned quarters, then fed.

” The word hung there, “Simple and impossible.

” Greta glanced at the woman beside her, Elsa.

A nurse from Hamburg, who had worked in a field hospital until the collapse.

Ilsa’s eyes were hollow, her cheekbones sharp beneath pale skin.

They had both lost weight during the journey across the Atlantic, crammed in the ship’s hold with hundreds of other prisoners.

The Red Cross had provided basic rations, but nothing that satisfied.

The truck rumbled through gates topped with wire, past wooden guard towers where soldiers watched with rifles resting easy in their arms.

No one shouted.

No one struck them.

The compound stretched wide rows of barracks, a parade ground, laundry lines strung between holes.

Women in similar uniforms moved between buildings, their movements slow in the heat.

This is where we’ll die, Elsa whispered in German.

They’re just being civilized about it.

But Greta wasn’t sure.

Something felt wrong about that assumption.

The guard’s faces held no malice.

The compound, though enclosed, looked clean.

organized, almost dot dot dot ordinary.

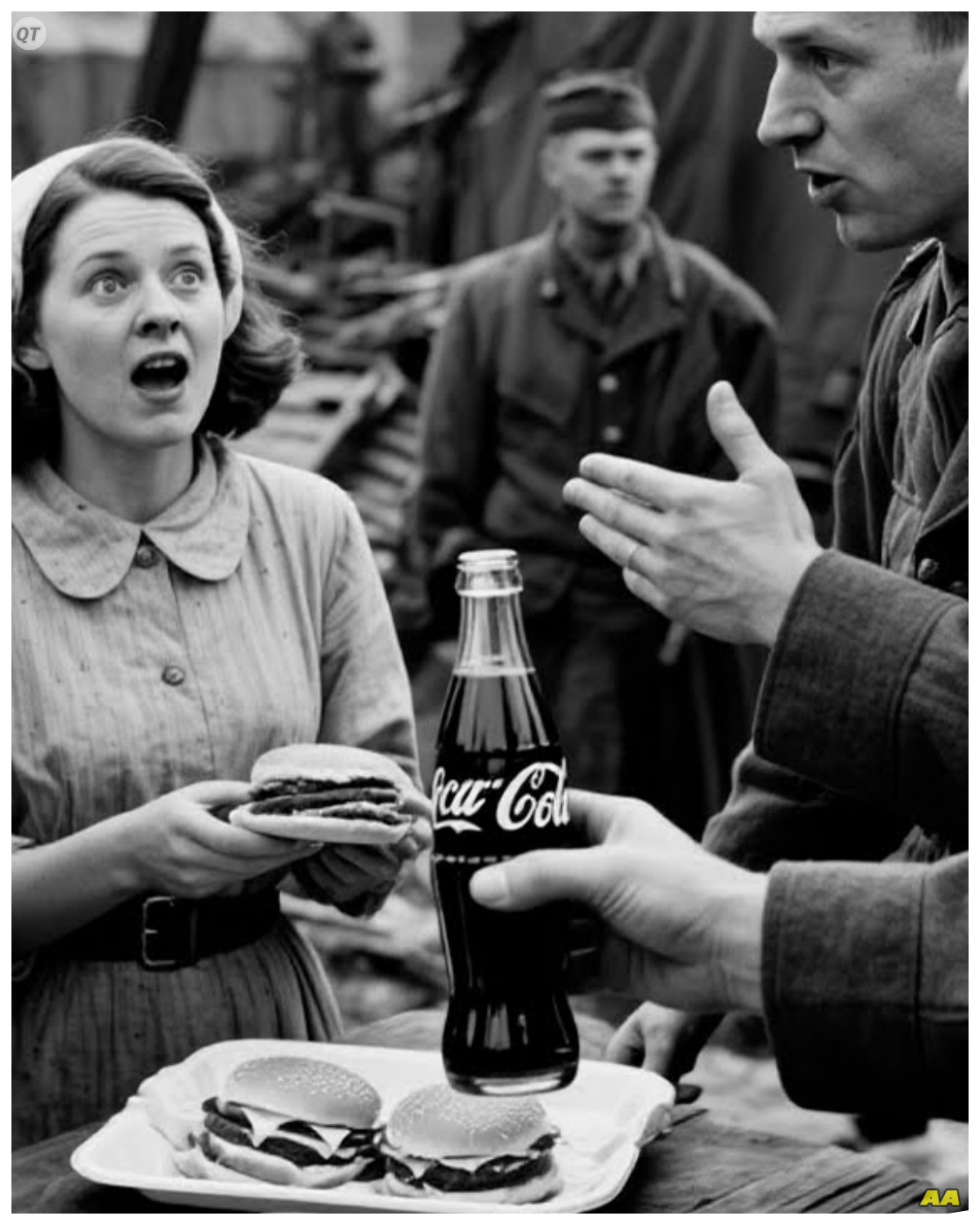

That first evening, they were led to the mess hall.

The building was long, low with screens on the windows to keep out insects.

Inside, ceiling fans turned slowly, moving hot air in lazy circles.

The smell hit them before they crossed the threshold meat cooking.

Fresh bread, something sweet and unfamiliar.

Coca-Cola.

They would learn the name later.

Long tables stretched the length of the room, and at the far end, American soldiers in white aprons stood behind serving stations, lifting lids off steaming trays.

Greeda’s stomach clenched.

She hadn’t smelled real food abundant food since before the war.

In Germany, rations had dwindled to turnipss and black bread, then less.

“Form a line,” the officer said in German.

His accent was textbook perfect, learned from classes, not life.

They shuffled forward, uncertain.

The American cooks watched them approach with expressions Greta couldn’t read.

One was older, maybe 40, with thick forearms and a stained apron.

He smiled when she reached the counter, a genuine thing that crinkled his eyes.

“Hungry?” he asked in English? She nodded, not trusting her voice.

He loaded her tray.

A hamburger thick and dripping juice.

Green beans cooked with bacon.

Mashed potatoes with butter melting into yellow pools.

White bread with more butter.

And at the end of the line, a young soldier handed her a cold bottle.

Dark glass sweating condensation.

“Coca-Cola,” he said, pronouncing it slowly.

“You’ll like it.

” Greta carried her tray to a table, movements careful.

afraid something would shatter the illusion.

Around her, the other women sat in silence, staring at their plates.

Elsa sat across from her, tears running down her face, making no sound.

“It’s a trick,” someone whispered in German.

“They’ll take it away,” but no one came to take it away.

The American guards stood by the doors, relaxed, talking among themselves.

The cooks began cleaning their stations, scraping trays, laughing at some private joke.

Greta lifted the hamburger.

The bun was soft, yielding beneath her fingers.

She bit and the taste exploded salt, fat, char from the grill.

Her body responded before her mind could catch up.

Trembling with need, she ate slowly, forcing herself not to devour it, not to make herself sick.

Beside her, a woman named Anna drank the Coca-Cola and gasped.

“What is this?” “Sugar,” Ilsa said, her voice thick.

“It’s just dot dot.

Sugar and bubbles.

” They ate in silence.

The only sounds the scrape of forks on metal trays, the hiss of carbonation escaping bottles.

When Greta finished, her plate empty except for smears of grease, she looked up at the serving station.

The older cook was watching them, his expression unreadable.

She stood.

Her legs felt weak, but she walked to the counter, pulse hammering in her throat.

The cook straightened, curious.

“Can we have leftovers?” she asked in broken English, the words coming out smaller than she intended.

He frowned, not understanding at first.

Then his face cleared, and he laughed, not mockery, but surprise tinged with something that might have been sadness.

“Leftovers?” he glanced back at the trays, still half full.

“Ma’am, this is all for you.

You can eat as much as you want.

That’s how it works here.

” She stared at him.

Behind her, the other women had stopped eating, listening.

“Go on,” he said, gesturing.

“Get whatever you want.

There’s plenty more where that came from.

Nobody moved.

The impossibility of it, the sheer abundance was too much.

They had been trained to scarcity, to rationing, to stealing crusts from each other in the night.

This generosity felt like a trap or a dream that would end when they woke.

But the cook just kept smiling, patient, and eventually Anna stood, walked to the counter, and held out her tray.

He loaded it again, whistling some tune Greta didn’t recognize.

One by one, the others followed.

That night, lying on her cot in the barracks, Greta felt something inside her shift.

Not breaking changing.

The propaganda had been clear.

Americans were decadent, wasteful.

Their softness would be their downfall.

But what she’d seen wasn’t softness.

It was something else.

something that scared her more than cruelty would have.

They had plenty, and they were willing to share it, even with enemies.

The routine established itself over the following weeks.

Wake at dawn when light turned the barracks gold.

Roll call in the parade ground.

Names checked against lists, then work assignments, laundry, kitchen duty, maintenance, clerical tasks.

The Americans kept them busy but not brutalized.

There were rules, structure, but no beatings, no starvation.

Greta was assigned to the Kev Laundry, a long building thick with steam and the smell of soap.

She worked alongside American women local civilians hired by the military, housewives, and mothers earning extra money.

At first, they didn’t speak.

The American women eyed the German prisoners with suspicion, their movements careful, guarded, but silence erodess faster than stone.

One morning, an American woman named Betty dropped a basket of wet sheets.

They spilled across the concrete floor, and she cursed, a sharp word that needed no translation.

Greta moved automatically, kneeling to help gather the fabric.

Betty hesitated then joined her and for a moment they worked together hands moving in synchronized rhythm.

“Thank you,” Betty said when they finished.

“Bit,” Gret replied, then corrected herself.

“You’re welcome,” Betty’s eyes widened.

“You speak English?” “A little from school.

Where’d you go to school?” “Berlin, before the war?” Betty nodded slowly, processing this.

Then my son’s over there in Germany with the occupation forces.

Greta didn’t know what to say.

The distance between them was too vast, built from years of propaganda and blood.

But they were standing in the same room, folding the same sheets, breathing the same humid air.

“I hope he’s safe,” Greta said finally.

Betty looked at her for a long moment.

Then she smiled, small and sad.

Me, too.

The compound had a library, a small room lined with donated books.

Greta discovered it by accident one Sunday afternoon, wandering between buildings to escape the heat.

Inside, it was cooler, quieter.

Shelves held volumes in English, German, even a few in French.

She ran her fingers along spines, reading titles.

“You like to read?” she turned.

An American chaplain stood in the doorway, collar marking him as clergy.

He was older, maybe 50, with gray threading his dark hair.

“Yes,” she said.

“I studied literature at university before the war.

” “Yes,” he nodded, understanding the weight of those two words.

“You’re welcome here, anytime.

Take whatever you want.

” She selected a book Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises in English.

The chaplain watched her expression thoughtful.

“Can I ask you something?” he said.

She tensed.

“Yes, what did they tell you about us? About Americans?” The question surprised her.

She had expected judgment, interrogation about loyalties or politics.

“Not this, that you are greedy,” she said carefully.

wasteful that you cared only for money and comfort that you had no culture no discipline and now she looked down at the book in her hands now I don’t know what to believe he smiled not triumphant just sad good doubt is the beginning of understanding later she would learn he had fought in the first war had seen German trenches and German dead had carried those memories for 25 years.

But he bore no hatred that confused her most of all.

Summer deepened.

The heat became something alive, pressing down on the compound like a physical weight.

Work continued laundry, kitchen duty, clerical tasks that moved slower, languid in the thick air.

One afternoon in July, during a rare break, the women gathered in the shade of their barracks.

An American guard approached, young, maybe 19, carrying a crate.

He set it down with a wooden thunk.

“Figured you ladies could use something cold,” he said in careful German.

The crate held bottles of Coca-Cola, glass wet with condensation.

He opened them one by one, using a metal opener hooked to his belt, and handed them out.

The women accepted them hesitantly, still unused to kindness without expectation of payment.

Elsa took a long drink, then lowered the bottle.

Why are you doing this? The guard looked confused.

Doing what? Being kind.

We’re your enemies.

He considered this, scratching his jaw.

Wars over.

You’re just people now.

Just people.

The simplicity of it was revolutionary.

Greta drank her Coca-Cola slowly, letting the sweetness coat her tongue.

Around her, conversations started halting at first, then flowing faster.

The guard sat down in the dirt, legs stretched out, and told them about his hometown in Kansas, about wheat fields that went on forever, about his girlfriend who wrote him letters every week.

“What will you do when you go home?” he asked Elsa.

She shook her head.

I don’t know if I have a home to go back to.

Hamburg was bombed.

My parents.

I haven’t heard from them.

His face fell.

I’m sorry.

It’s not your fault.

But it was someone’s fault, wasn’t it? That was the terrible thing.

All this destruction, all this suffering could be traced back to decisions made in rooms far from here.

And yet, sitting in the dirt drinking Coca-Cola, it felt distant, almost unreal.

That evening, writing in the journal she’d been given by the chaplain, Greta tried to capture the feeling.

We are enemies who drink together.

We are prisoners who laugh with our guards.

Nothing makes sense anymore.

And perhaps that’s the point.

Perhaps the world only makes sense when we stop trying to fit it into the shapes we veb and taught.

August brought news of the Japanese surrender.

The war was over.

Truly, finally over.

The compound erupted in celebration.

American soldiers shouting, throwing caps in the air, embracing each other.

The German women watched from the barracks, uncertain how to react.

That night, the Americans threw a feast.

The mess hall was decorated with streamers.

A band set up in the corner soldiers with instruments playing swing music that echoed off the walls.

The cooks had outdone themselves.

Mountains of hamburgers, hot dogs, potato salad, coleslaw, apple pie cooling on racks.

“Come on,” Eddie said, appearing at the barrack store.

“You’re invited.

We’re prisoners,” Greta said.

“Tonight, your guests.

Come eat.

” They filed into the mess hall, awkward in their presence among celebrating soldiers.

But the Americans made space, pulled out chairs, handed them plates piled high with food.

The band played louder, and someone Greta never learned who grabbed Ilsa’s hand and pulled her into a dance.

She watched Ilsa spin, laughing for the first time since they’d arrived.

Her thin frame moving to music that had no nationality, no politics, just rhythm and joy.

Around them, soldiers danced with each other, with civilian workers, with German prisoners, all distinctions blurring in the movement.

An American corporal, red-faced and grinning, approached Greta.

Dance? She hesitated.

I don’t know how.

Not this music.

Neither do I, he admitted.

We’ll figure it out.

They moved to the floor, clumsy and laughing, stepping on each other’s feet.

The hamburger grease on her fingers mixed with the sweat on his palm, and the smell of food and bodies and summer heat filled her lungs.

She felt dizzy, overwhelmed, like she’d stepped into someone else’s life.

Later, sitting at a table, plate empty, bottle of Coca-Cola sweating in her hand, she watched the celebration continue.

The war was over.

Millions were dead.

Cities were rubble.

Families were destroyed and here they were dancing.

Doesn’t make sense, does it? The chaplain had appeared beside her, his own plate balanced on his knee.

No, she agreed.

Good things and terrible things exist at the same time.

That’s the hardest lesson.

She looked at him.

How do you live with that? You choose which one to feed.

Every day you wake up and choose.

The band played on.

Soldiers laughed.

Somewhere in Germany, people dug through rubble looking for survivors.

Both things were true.

Both things mattered.

September brought cooler air and news of repatriation.

The German women would be sent home those who had homes to return to.

The process would take months, paperwork, and logistics, but it was beginning.

Greta wrote letters in the library using paper the chaplain provided.

She wrote to friends, to distant relatives, to anyone she thought might still be alive.

She described Texas, the compound, the Americans who had been their capttors and their hosts.

“You won’t believe what they gave us,” she wrote to her sister, if her sister still lived.

“Hamburgers and Coca-Cola.

Real butter, white bread everyday.

They treated us like human beings, not like the enemy.

I don’t understand it.

We were told they were monsters.

But they were just people.

Young men who wanted to go home.

Women who worried about their sons.

Cooks who took pride in their work.

Just people.

She paused, pen hovering over paper.

I don’t know what I believe anymore about anything.

The world they described to us doesn’t exist.

Or maybe it does somewhere, but not here.

Here, people are just people.

And that’s more complicated and more simple than anything I was taught.

Around her, other women wrote similar letters.

Elsa wrote to the Red Cross asking them to search for her parents.

Anna wrote to a cousin in Switzerland describing the Coca-Cola, trying to explain what sweetness tasted like after years of deprivation.

The chaplain read their letters he had to.

Regulations required it, but he never censored them.

Tell the truth,” he said.

“People need to hear it.

” December came cold, the Texas winter mild by German standards, but shocking after the summer heat.

The repatriation orders arrived, assigning women to different ships, different departure dates.

Greta’s group would leave in January.

On their last night, the Americans threw another feast.

Not a celebration this time, but a farewell.

The mess hall was warm, windows fogged with steam.

The cooks had prepared all the foods the women had come to recognize.

Hamburgers, hot dogs, apple pie, Coca-Cola in bottles, cold enough to burn bare hands.

Betty came dressed in her Sunday best.

She brought Greta a small gift wrapped in brown paper cookbook, American recipes written in English.

So you can remember,” Betty said.

Greta held it carefully.

“I won’t forget.

Will you look for my son?” “When you get back.

” “His name is Robert Mitchell.

” He stationed in Frankfurt.

“I’ll try.

” They embraced, awkward and genuine.

Two women from different worlds who had found something like friendship in the steam of a laundry room.

The feast continued late into the night.

Soldiers told jokes.

The women laughed, understanding more English now than when they’d arrived.

Someone produced a camera and photographs were taken grainy black and white images that would survive in atticss and albums.

Evidence of this strange moment when enemies became something else.

Greta ate slowly, savoring each bite.

The hamburger tasted the same as it had that first night 6 months ago, but everything else had changed.

She had changed.

The propaganda had dissolved like sugar in water, leaving behind something clearer, more truthful.

“What will you tell people?” the young guard from Kansas asked.

“When you get home,” she considered this the truth.

That you gave us hamburgers and Coca-Cola.

That you treated us with dignity when you had every reason not to.

That you were just people like us.

Think they’ll believe you? I don’t know, but I’ll tell them anyway.

January 1946, the women boarded trucks in the pre-dawn darkness, breath visible in the cold air.

Their few possessions fit in small bags, the clothes they’d arrived in now clean and mended, gifts from American soldiers and workers, letters they’d received and written.

Greta carried Betty’s cookbook, the chaplain’s journal, and a single photograph.

Her and Elsa and Anna standing outside the mess hall, smiling at the camera.

Behind them, an American soldier, the one from Kansas, had his arm around Ilsa’s shoulders, casual and friendly.

Evidence of a world that made no sense according to what they’d been taught.

The trucks rolled through the gates.

In the rear view mirror, Greta watched the compound recede the barracks, the mess hall, the laundry building where she’d spent 6 months folding sheets beside women who had been strangers, then co-workers, then something like friends.

Texas unfolded around them, the landscape golden in the morning light.

They drove to the port where ships waited to carry them home.

Home, the word felt strange.

What was home now? Cities in rubble, families scattered or dead, a Germany she wouldn’t recognize.

At the dock, the chaplain was waiting.

He shook each woman’s hand, spoke words of blessing, gave them pamphlets with addresses of aid organizations.

When he reached Greta, he pressed something into her palm, a small wooden cross, handcarved, the grain still visible.

Remember, he said, doubt is the beginning of understanding.

She nodded, unable to speak around the thickness in her throat.

The ship’s horn blew deep and mournful.

They climbed the gang plank, the metal cold beneath their feet.

On deck they stood at the rail, watching the American coast recede.

The port grew smaller than the land itself until there was only water, gray and endless.

“What do we do now?” Elsa asked.

Greta touched the cookbook in her bag, felt the outline of the cross in her pocket.

We rebuild.

We tell the truth.

We tried to be the kind of people who would share their hamburgers with their enemies.

That simple? That complicated? The ship pushed forward, carrying them toward a continent destroyed, toward uncertainty and struggle and the long work of reconstruction.

But in Greta’s memory, preserved like a photograph, was the image of that first night, the messaul, the abundance, the American cook laughing when she asked for leftovers.

“This is all for you,” he’d said.

“And in that moment, something had broken.

Not her spirit or certainty.

The wall between enemy and human had cracked, and through it had poured doubt, confusion, and finally, reluctantly, understanding.

The propaganda had taught her.

Americans were wasteful, greedy, soft.

They were all those things perhaps.

But they were also generous, kind, willing to see humanity even in those they’d been taught to hate.

And that generosity, that willingness to share hamburgers and Coca-Cola with women who dee stood on the other side of war, had done more to defeat the ideology she dee been raised in than any bomb or bullet ever could.

The archives hold their records.

Greta Zimmerman returned to Berlin, found her sister alive, worked as a teacher for 30 years.

She kept the cookbook, the pages yellowed and stained, and taught her students about the Americans who’d given her hamburgers.

Ilsa Vber found her mother in Hamburg, her father gone.

She became a nurse again, worked in a hospital, helping rebuild what the war had destroyed.

Every year on August 15th, she bought a bottle of Coca-Cola if she could find one and drank it slowly, remembering Anna Fischer married an American soldier she met during the occupation, moved to Ohio, opened a restaurant.

She served hamburgers the way she’d learned in that Texas messaul, and told anyone who asked about the women who’d been prisoners and guests, enemies and friends, all at once.

A chaplain died in 1952.

His papers donated to the army archive.

Among them, letters from German women he’d helped, thanking him for teaching them that doubt was holy, and uncertainty was the beginning of wisdom.

Betty Mitchell’s son came home from Germany, married, had children.

He never knew his mother had befriended a German prisoner, had given her a cookbook, had found common ground in the steam of a laundry room.

But the records exist.

The photographs survive.

Grainy black and white images of women in prison uniforms smiling at the camera holding bottles of Coca-Cola.

Behind them, American soldiers, young and old, guards and prisoners.

All just people caught in the machinery of history trying to find humanity in the wreckage.

The hamburgers are long eaten, the Coca-Cola long drunk.

But what they represented, abundance in the face of scarcity, kindness despite enmity, the stubborn insistence that even enemies are human survives.

In the end, that’s what defeated the ideology more completely than any military campaign.

Not bombs, not occupation, not tribunals, just simple acts of generosity repeated daily until the propaganda couldn’t hold against the weight of lived experience.

One woman asked, “Can we have leftovers?” And the answer changed everything.

News

German General Evaded Arrest in the Final Days — 79 Years Later, His Remote Alpine Refuge Was Found

In the final chaotic hours of World War II, as Allied forces closed in from all sides and the Third…

🐘 Nike’s Shocking Choice: Alex Eala’s $45 Million Contract Leaves Sabalenka in the Shadows! 🌪️ “One moment in the spotlight can change everything!” In an unexpected twist, Nike has announced a groundbreaking $45 million contract for tennis prodigy Alex Eala, effectively sidelining Aryna Sabalenka. As the tennis world buzzes with speculation, the implications for both athletes are immense. Can Sabalenka reclaim her position, or will this snub redefine her career? The drama unfolds as the competition heats up! 👇

The Shocking Snub: Nike’s $45 Million Contract for Alex Eala Leaves Aryna Sabalenka Reeling In a dramatic turn of events…

🐘 Revenge Motive Explored: Forensic Expert Raises Alarming Questions in Guthrie Case! ⚡ “The past has a way of catching up with us, especially in matters of revenge!” A renowned forensic expert has put forth a chilling theory that revenge may be a key motive in the ongoing investigation of Nancy Guthrie’s case. As the implications of this theory unfold, the community is left to ponder the relationships and rivalries that could have led to such a drastic act. Will this insight lead to the breakthrough everyone has been waiting for, or will it deepen the mystery? 👇

The Dark Motive: Revenge Uncovered in the Nancy Guthrie Case In a shocking revelation that feels like the climax of…

🐘 Emergency Alert: Boeing’s Departure from Chicago Sends Illinois Into a Frenzy! 💣 “Sometimes, the sky isn’t the limit—it’s the beginning of a downfall!” In an unprecedented move, Boeing has announced it will shut down its Chicago operations, leaving the Illinois governor scrambling to manage the fallout. As uncertainty looms over thousands of jobs and the local economy, the political ramifications are vast. Can the governor stabilize the situation, or is this just the beginning of a much larger crisis? The clock is ticking! 👇

The Boeing Exodus: Illinois Governor Faces Crisis as Jobs Fly Away In a shocking turn of events that has sent…

🐘 Nancy Guthrie Case Takes a Dramatic Turn: New Range Rover Evidence Discovered! 🌪️ “Sometimes, the truth rides in style!” In a shocking turn of events, authorities have unearthed new evidence related to a Range Rover that could change everything in the Nancy Guthrie case. As the investigation heats up, questions abound: what does this mean for the timeline of events? With emotions running high and the community demanding answers, the stakes have never been greater. Will this lead to a breakthrough, or is it just another twist in a long and winding road? 👇

The Shocking Revelation: New Evidence in the Nancy Guthrie Case Changes Everything In a gripping twist that feels ripped from…

🐘 Lawmakers Erupt: Mamdani’s Deceitful Campaign Promises Under Fire! 💣 “Trust is the currency of politics, and Mamdani is bankrupt!” In a dramatic clash, lawmakers have slammed Mamdani for betraying the trust of New Yorkers with his hollow promises. As the investigation unfolds, the community is left in shock—what does this mean for the future of leadership in the city? With public confidence at an all-time low, the pressure is on Mamdani to make amends or face the consequences of his actions. The clock is ticking! 👇

The Reckoning: Zohran Mamdani’s Broken Promises and the Fallout In the heart of New York City, a storm is brewing…

End of content

No more pages to load