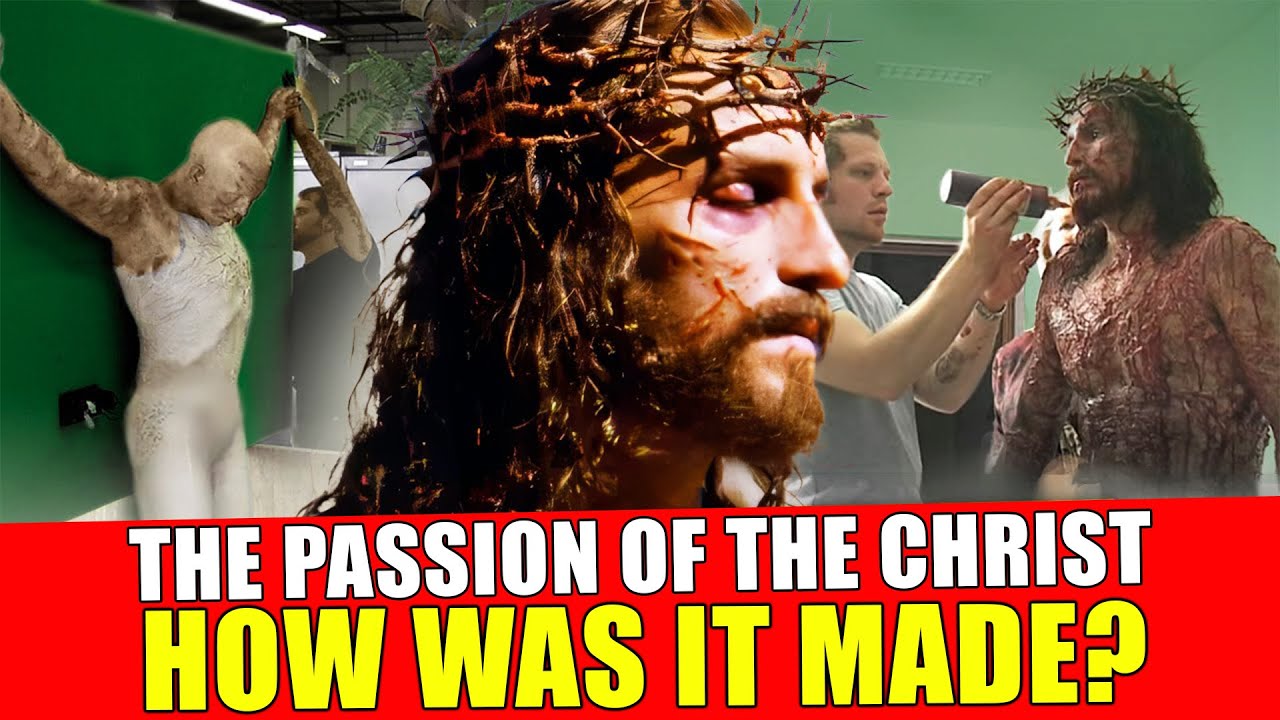

What if I told you that The Passion of the Christ, one of the most powerful films ever made, almost broke the man who played Jesus?

Behind every frame of that 2004 masterpiece lies a story few people have ever heard—nights without sleep, lightning strikes, prosthetic experiments, and moments when fiction and faith blurred so deeply that even a priest thought Jim Caviezel had died on set.

Mel Gibson’s vision for The Passion was never about comfort.

He didn’t want a movie that simply retold the gospel.

He wanted the audience to feel the pain, the love, and the unbearable realism of the crucifixion.

To achieve that, his team combined never-before-used makeup techniques, animatronics so lifelike they fooled even professionals, and visual effects that would change filmmaking forever.

But the cost was immense—physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

The film tested every person involved, becoming not just a production, but a trial of faith.

In this video, we’ll uncover the shocking behind-the-scenes secrets of The Passion of the Christ.

How were the effects created?

What really happened to Caviezel?

And why does this movie remain both a cinematic miracle and a human ordeal?

When Jim Caviezel accepted the role of Jesus Christ, he knew it would change his career.

But he didn’t realize it would also change his body, his sleep, and, in many ways, his soul.

Each morning began before dawn—3 to 4 hours just to become recognizable as the man the world knows from scripture.

But this wasn’t ordinary makeup.

Mel Gibson wanted the audience to see every stage of suffering, from the first blows in Gethsemane to the final breath on the cross.

That meant nine separate phases of prosthetic transformation designed to evolve as the story descended into agony.

The process was brutal.

Layers of silicone wounds, swollen eyes, dried blood, and torn flesh were applied by hand.

Caviezel sat motionless for hours while artists built suffering directly onto his skin.

And yet, those artists weren’t simply creating horror—they were sculpting empathy.

Every bruise was placed with purpose.

Every swelling was measured against the story’s emotional rhythm.

But here’s where things got even more extreme.

The schedule was relentless.

25 shooting days, often in freezing Italian nights.

There was no way to spend 8 hours applying makeup and still have time to film.

So, the team invented something revolutionary: the prosthetic transfer technique.

Inspired by temporary tattoos, instead of gluing layers piece by piece, they created 3D wounds on giant sheets of film paper that could be transferred with water.

This cut preparation time from 8 hours to just two, saving the production and, indirectly, saving Caviezel’s health.

The innovation was so groundbreaking that four years later, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences quietly recognized it with a technical achievement award.

But during filming, there was no glamour—only exhaustion.

The crew sometimes worked 20-hour days.

When rain or wind shut down filming, Caviezel would sleep still covered in fake blood because removing and reapplying it would take longer than the rest itself.

Those were the nights, he later said, when he stopped acting and started praying.

This wasn’t makeup anymore.

It was ritual.

A ritual that blurred the line between cinema and faith, pain and devotion.

Mel Gibson didn’t want illusion.

He wanted incarnation.

He once told the crew, “If the audience doesn’t flinch, we failed.”

To capture that level of realism without physically destroying his actor, the special effects team built something Hollywood had never seen before: a full-size animatronic replica of Jim Caviezel.

The challenge was enormous.

Caviezel was rapidly losing weight during filming—both intentionally for the role and due to the punishing schedule.

The crew had to predict how much thinner he’d become by the time crucifixion scenes were shot.

So, they built the animatronic from the inside out.

First, the metal skeleton.

Then, the servo motor joints.

Then, the silicone flesh, textured to perfection.

This replica could do things no prop ever had.

Its chest expanded and contracted like it was breathing.

Its head tilted and rotated.

Even its hands and wounds could bleed through internal tubing that pumped artificial blood at timed intervals.

From a distance, it looked alive—too alive.

During one particularly intense sequence, a visiting priest saw the animatronic Jesus hanging lifelessly between takes.

When the technician switched it off, and its breathing stopped, the priest screamed for help, believing Caviezel had died on the cross.

The crew rushed in, trying not to laugh and cry at once.

When they showed him the hidden motors and tubing, he reportedly whispered, “God forgive me. I believed.”

Moments like that summed up Gibson’s set.

The boundary between realism and reverence vanished.

There was laughter, too.

The dark, necessary kind that keeps people sane.

Between takes, Gibson would crack jokes, splash fake blood on himself, or even act out scenes to relieve tension.

Because what they were shooting wasn’t just drama.

It was trauma recorded in high definition.

Even the sets themselves were born from ingenuity.

The massive Roman courtyard and temple interiors weren’t freshly built—they were repurposed from Gangs of New York.

Gibson’s team transformed them with biblical details and weathering techniques.

Proving that cinematic vision doesn’t require blockbuster budgets—only conviction.

But that conviction came at a cost.

The weight of that vision—the intensity, the exhaustion, the physical demands—began to mirror the very passion the film sought to portray.

And soon, that weight would fall squarely on the actor carrying the cross to play the Son of God.

Jim Caviezel had to walk through something disturbingly close to crucifixion.

Gibson’s cameras captured agony that looked real because for Caviezel, much of it was.

The production pushed realism to its breaking point.

During the scourging scene, steel plates were strapped to Caviezel’s back to protect him from the Roman whips.

Yet, two strikes missed their mark.

One lash tore into his skin so deeply that he couldn’t breathe.

The crew froze, terrified they had actually injured their Christ.

Rather than discard the footage, they studied the wound, replicated it in prosthetic form, and used it to heighten authenticity.

But that was only the beginning.

The wooden cross used in filming weighed nearly 70 kilos.

Gibson refused lightweight replicas—he wanted to see the burden in Caviezel’s body.

In one take, the cross slipped, slammed onto his shoulder, and dislocated it.

In another, it crashed against his head, splitting his lip and leaving him concussed.

Yet, Caviezel insisted on continuing.

“If He carried it, so can I,” he reportedly said.

Cold Italian winds lashed the hilltop where the crucifixion was filmed.

Caviezel wore little more than a loincloth, shaking uncontrollably as his body temperature dropped toward hypothermia.

The crown of thorns pressed so tightly against his skull that blood and prosthetic glue mixed in his hair.

He developed migraines and temporary vision loss from a swollen eye.

And then came lightning.

During a pause in filming, a bolt struck the actor’s cross and traveled through the metal rigging into his body.

Miraculously, he survived with only minor burns.

But the incident left him shaken, convinced that something larger than cinema was unfolding around them.

Behind the cameras, the crew prayed quietly.

Between takes, Gibson sometimes joined them, kneeling in the mud.

What had started as a film set turned into a kind of pilgrimage, a living stations of the cross.

Even for those who weren’t believers, something sacred had taken hold.

Technicians who had never opened a Bible were suddenly asking about forgiveness, redemption, and sacrifice.

The realism was no longer a cinematic choice.

It had become spiritual contagion.

This part of the shoot revealed the paradox of The Passion of the Christ.

It was a movie about suffering made by people who were suffering to tell it truthfully.

Every frame was purchased in pain, but also in prayer.

Every filmmaker has a limit—a point where art must yield to practicality.

Mel Gibson didn’t believe in that limit.

If something looked false, he’d scrap it.

If it felt too clean, he’d dirty it again.

The Passion of the Christ had to look not like a film, but like a memory burned into the human soul.

The crucifixion sequence demanded everything they had learned, every trick, every risk.

It combined brutal realism with startling ingenuity to show the nail-piercing Christ’s hand.

The effects team built a special wooden cross with a hidden opening beneath Caviezel’s palm.

His real hand was lowered into the hollow while a fake extended hand, complete with mechanical fingers, was attached above.

Through careful camera placement, the audience saw what appeared to be a real hand struck by a real iron spike.

The result was haunting.

Even seasoned crew members looked away as the camera rolled.

But the most complex scenes weren’t of pain.

They were of symbolism.

The moment the temple veil tore in two, marking the rupture between heaven and earth, was achieved through camera choreography—not computer graphics.

Two cameras were mounted in a V-shape on set.

At the signal, they pulled apart simultaneously, capturing the walls as though the building itself were splitting open.

Later, the team overlaid these shots with a miniature temple floor, built at 1/5 scale, to complete the illusion of an earthquake cracking the sacred stone.

And when they realized they’d forgotten to film the veil actually ripping, they didn’t rebuild the set.

They painted it digitally—thread by thread, fire and dust swirling through the divide.

It was a subtle reminder. Even miracles sometimes need a touch of technology.

One of the most visually poetic moments came near the end.

A single drop of water fell from the sky onto Golgotha.

What looked like a simple shot actually combined four layers:

A miniature landscape.

Blue screen footage of the cross.

High-speed photography of real droplets.

And digital particle effects for the dust cloud.

In that instant, when heaven’s tear hits the earth, The Passion of the Christ transcended realism and entered the realm of theology on film.

This fusion of art and faith defined Gibson’s entire approach.

Ancient pain expressed through modern craftsmanship.

No expensive CGI armies, no sterile, impersonal effects—just raw, emotional filmmaking.

News

HOLLYWOOD IN PANIC MODE: THE “NON-WOKE” REVOLT HAS BEGUN! A BILLION-DOLLAR “MIDDLE FINGER” TO THE ELITES!

HOLLYWOOD IN PANIC MODE: THE “NON-WOKE” REVOLT HAS BEGUN! A BILLION-DOLLAR “MIDDLE FINGER” TO THE ELITES! In a move that…

California’s Wells Fargo Tower Sells at 65% LOSS — Downtown LA Is COLLAPSING

California’s Wells Fargo Tower Sells at 65% LOSS — Downtown LA Is COLLAPSING In the heart of downtown Los Angeles,…

ICE & FBI Raid Somali Law Firm in Minneapolis — 400 Arrests, 28 Dirty Cops & $50M Fentanyl SEIZED

ICE & FBI Raid Somali Law Firm in Minneapolis — 400 Arrests, 28 Dirty Cops & $50M Fentanyl SEIZED In…

Democrats Suffer MAJOR BLOW as Alex Pretti’s Past is EXPOSED

Democrats Suffer MAJOR BLOW as Alex Pretti’s Past is EXPOSED In a shocking turn of events, recent revelations about Alex…

Governor of California Faces Healthcare Crisis: 31,000 Kaiser Workers Announce INDEFINITE STRIKE

Governor of California Faces Healthcare Crisis: 31,000 Kaiser Workers Announce INDEFINITE STRIKE On January 26, 2026, a historic labor action…

Governor Of Oregon PANICS After Washington Refineries Begin Closing!

Governor Of Oregon PANICS After Washington Refineries Begin Closing! Oregon’s Fuel Future in Peril as Phillips 66 Signals More Refinery…

End of content

No more pages to load