Trust and Shadows: Diya’s Journey from Chandipur to Mumbai

I always believed my grandmother loved me deeply, which is why she insisted on taking our daughter Diya to stay with her in Chandipur village. From the day Diya was born, Grandma Sarla showered her with affection. Whenever asked, she’d proudly say:

— “You should leave her with Grandma. I care for her more than her own mother ever could. The village air is pure, and the neighbors are warm and caring.”

My husband and I live in Mumbai, and these words comforted us. Seeing Diya eat well, cry less, and thrive in the village filled our hearts with relief: “She truly is better off in Grandma’s care.”

Three months slipped by quickly. One afternoon, Grandma’s neighbor Sita called, her voice trembling:

— “You both need to come back to Chandipur right away… before it’s too late!”

Panic-stricken, we raced to the village by car. As we entered the red-brick courtyard, a chill ran down our spines: our little Diya was curled up in her room, her body frail, her eyes vacant. On Grandma’s wooden bedside table sat bottles of sleeping pills and strong sedatives, labeled in Hindi—some prescriptions meant only for adults with severe depression.

Sita’s voice broke as she explained:

— “Grandma gave her ‘tonics’ every day to help her eat, sleep, and be obedient. At first, I thought it was harmless, but seeing Diya grow weaker each day, we became suspicious…”

It felt like lightning had struck us. We searched the medicine cabinet, our hearts sinking—every bottle was a sedative, some intended only for adults with serious conditions.

Seeing us, Diya burst into tears, her voice trembling:

— “Mama… I’m scared… After taking those pills, I just slept all the time. I can’t play anymore…”

Neighbors tried to hold back Grandma Sarla, who sobbed:

— “I was afraid she’d be naughty, afraid you’d struggle in Mumbai. So I gave her something to make her obedient. Who could have imagined…”

The air in the tiled-roof house felt suffocating. My husband and I clung to our child, hearts heavy with pain and betrayal. All that remained of our trust in Grandma and our love for Uttar Pradesh was bitterness.

That night, we rushed Diya to the district health center, then straight to a hospital in Lucknow. Harsh white lights, the constant beep of blood pressure monitors, the sharp scent of disinfectant. Diya lay on a hospital bed, a tiny IV in her hand, her lips cracked and dry. The pediatrician lowered his mask and looked at us for a long moment:

— “Fortunately, you brought her in time. Repeated sedatives have exhausted her body. From now on, don’t give her anything yourself. She’ll need monitoring and gentle psychological care to restore her sleep.”

I squeezed Raghav’s trembling hand. He nodded repeatedly, eyes red. In the corner, a small Ganesh idol sat—I silently prayed: “Let her recover… Give me the courage to protect her.”

Early next morning, Grandma Sarla arrived, standing quietly behind the door, her sari faded, pallu fluttering. Sita came “to keep the peace.” Raghav pressed my hand, then turned to his mother:

— “Mom… why?”

Grandma looked at Diya, then at us. Her voice was heavy:

— “I was scared… In the village, children run in the courtyard, climb on the well, chase chickens. Once, my niece fell into the pond behind the house. She was Diya’s age. Since then, I’ve never had the courage to take my eyes off children. I thought… if she slept more, ran less, she’d be safer…”

I was stunned. I’d never heard this story before. Sita Auntie nodded and whispered:

— “Years ago, Sarla’s husband’s sister Anaya passed away young. The accident happened when Grandma had stepped into the kitchen… Since then, there’s been a ‘wound’ in her heart.”

I watched Diya’s gentle breathing, my heart tangled between anger and sorrow. But love can never justify hurting a child.

The doctor advised two more days in the hospital. We took turns keeping watch. Whenever Diya opened her eyes, she’d whisper:

— “Mommy, I don’t want to sleep anymore… I want to play the drum at Grandma’s house.”

I comforted her:

— “Yes, you’ll sleep, but only when you’re well, Diya.”

On the third day, we returned to Chandipur to pack Diya’s things for her permanent move to Mumbai. News spread like wildfire. By noon, the village council—the panchayat—summoned our family, Grandma, and the owner of Verma Chemist to the courtyard beneath the neem tree.

Village head Mukesh began:

— “This concerns the safety of our children. Let’s be clear.”

Raghav placed a cloth bag full of empty bottles on the table: sleeping pills, sedatives, sleep-inducing eye drops… a bundle of receipts written in blue ink. Mr. Verma looked confused:

— “I only sell mild stuff… Grandma asked for ‘sleeping pills,’ said a doctor recommended them.”

I produced a crumpled paper—the “prescription” I’d found in Grandma’s drawer. The doctor’s signature was distorted, the stamp faint. Mukesh frowned:

— “This signature is fake. The stamp is wrong. At the community health station, only black ink is used.”

The courtyard fell silent. Grandma covered her face:

— “I… I didn’t know. The man at the counter said just a small dose would do. I only wanted her to be well and less troublesome…”

An elderly woman stood up:

— “Even love needs discipline. Children cry—it’s natural. Soothe them, play with them. Why ‘put them to sleep’ with medicine?”

Sita recalled the days she saw Diya limp and weak, trying to wave from behind the window bars, strength drained. I listened, my heart aching. Raghav’s final words:

— “We don’t want to shame anyone. But reckless selling of medicines must stop, especially for children.”

The council agreed: file a report, send it to the health center and police. Verma’s shop was warned and temporarily closed for inspection. Grandma was sent for psychological counseling in Lucknow—not as punishment, but to heal the old fears that had become harmful habits.

Before dispersing, Mukesh added:

— “If anyone has children and feels overwhelmed, call your neighbors, call the women’s group. Don’t resort to medicines. From now on, we’ll hold training sessions for child care in the village, with help from the Anganwadi.”

We nodded. Suddenly, I realized that even in a village that seemed closed off, there was room for change.

On our last night in Chandipur, I packed Diya’s favorite things: her drum, Sita Auntie’s handmade cloth doll, and the tiny silver bangles given by a cart vendor for her first birthday. Grandma stood on the porch, gazing inside, her eyes hollow.

— “May I… see Diya for a moment?”

I hesitated, then brought her out. Grandma knelt and touched her forehead to Diya’s:

— “Child, forgive Grandma. I was so afraid, I did something wrong. I’ll come to Mumbai, learn to care for children as the doctor says.”

Diya looked at me, then at Grandma:

— “Grandma… tomorrow I’ll go back to Mumbai… Don’t give me sleeping pills, tell me Hanuman’s story, okay?”

Tears streamed down my face. I held Grandma’s hand:

— “Mom, come with us to Mumbai for a while. But you must follow the doctor’s instructions. And everything… slowly, from the beginning.”

Grandma nodded, as if a child learning something new.

On the train leaving Faizabad, I sat by the window with Diya in my lap. Sugarcane fields, village roads, neem trees faded into the distance. Raghav rested his head against the seat, eyes closed. As Diya slept—a natural, deep, peaceful sleep—I opened the cloth bag Grandma had handed me before we left.

Inside was an old notebook, its cover worn. I opened it: crooked Hindi lines, Grandma’s diary from ten years ago. A paper slipped out—the death certificate of Anaya: “Fell into the pond behind the garden on 12/8…” Water stains still marked the corners. I read every line, as if listening to a long-suppressed sob. On the last page, Grandma had written in Hindi and shaky English:

“If I could go back to that day, I’d open the gate, let Anaya run across the courtyard. Even if she cried, I’d teach myself to stay calm. I can’t trade silence for false safety.”

I closed the book and took a deep breath. Forgiveness doesn’t erase consequences, but it can guide the future.

In Mumbai, Diya recovered faster than we’d hoped. She laughed at the trains passing by our chawl, watered tulsi plants on the balcony, asked her father to make paper kites. At bedtime, I told her the story of Hanuman carrying the mountain of herbs—instead of any “sleeping medicine.” When Diya turned restlessly, I’d open the window to let in the sea breeze, hold her close, and softly sing a lullaby.

Grandma came to the city, too. She went with me to the hospital, listened carefully to the doctor’s advice, took notes: “No honey for children under one, no over-the-counter cough medicine, no sedatives…” She attended counseling, learned to face her old fears. Sometimes, watching Grandma patiently count breaths with Diya, I saw a changed woman—less anxious, more attentive.

One afternoon, someone knocked. It was the local police. He showed Raghav a file:

— “The Verma Chemist case. We found many fake medicines—same font, same stamp. Someone’s been selling counterfeit stamps in these villages. That person… might not be Mr. Verma.”

I looked at Raghav. He said softly:

— “If you need a statement from my mother or any neighbor, we’re ready.”

The officer nodded and pulled out a paper from the file:

— “And here… do you recognize this signature? It matches the one on your mother’s ‘prescription.’”

I took the paper. Blue ink, hurried handwriting. In the corner, a strange mark—a tiny neem leaf. I shivered. That “neem leaf”… I’d seen it in Grandma’s diary, on the page with Anaya’s death certificate, where Grandma had drawn one herself.

I looked out at the balcony. Mumbai’s sky was gray with clouds. The wind rattled the clothesline, making a strange sound. Inside, Diya was counting “one, two, three” with Grandma, practicing deep breaths.

I closed the door, a sudden thought flashing: Who had marked the fake prescription with a “neem leaf”? Mr. Verma? An old acquaintance? Or… a figure the whole village believed had vanished with the wind beneath the neem tree years ago?

I squeezed Raghav’s hand:

— “We’ll see this through. Not just to reclaim Diya’s safety, but to dispel the darkness that drives people like Grandma to such desperate acts.”

Raghav nodded. Outside, the train whistle sounded again—long and echoing, like a promise.

News

I was ready to call the police, but when I saw the panic in her eyes, I simply sighed… Perhaps, kindness is sometimes a gamble.

I was ready to call the police, but when I saw the panic in her eyes, I simply sighed… Perhaps,…

On my way to buy groceries at the market, I accidentally overheard a chilling conversation between my husband and the butcher: “Please, otherwise if outsiders find out, there will be a huge commotion…”

On my way to buy groceries at the market, I accidentally overheard a chilling conversation between my husband and the…

“They Thought I Was Stubborn”: Kevin Costner, Harrison Ford, and Hollywood’s Sliding Doors

“They Thought I Was Stubborn”: Kevin Costner, Harrison Ford, and Hollywood’s Sliding Doors Imagine Hollywood in the late 1980s and…

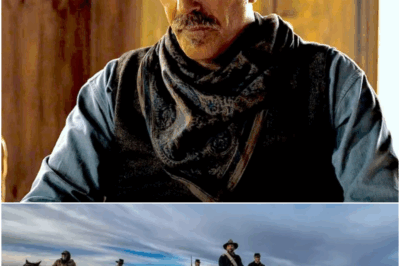

Stream It or Skip It? Kevin Costner’s ‘The West’ Delivers a Raw, Unfiltered Journey Through America’s Frontier

Stream It or Skip It? Kevin Costner’s ‘The West’ Delivers a Raw, Unfiltered Journey Through America’s Frontier What do you…

Kevin Costner’s Gamble: Can ‘Horizon’ Rewrite the Rules for Westerns and Streaming Success?

Kevin Costner’s Gamble: Can ‘Horizon’ Rewrite the Rules for Westerns and Streaming Success? Kevin Costner stands on the edge of…

The Media Revolution No One Saw Coming: Jon Stewart, Lesley Stahl, and the Showdown That’s Shaking the News Industry

The Media Revolution No One Saw Coming: Jon Stewart, Lesley Stahl, and the Showdown That’s Shaking the News Industry Hold…

End of content

No more pages to load