This is not the story of the gunshots themselves. Those seconds on Elm Street have been analyzed, replayed, and argued over for decades. Instead, this is the story of what came after—the hours, days, and decisions that followed President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and how they exposed a deeper struggle over power, grief, ritual, and control in America.

On the morning of November 22, 1963, President Kennedy arrived at Dallas Love Field amid cheers, smiles, and optimism. The motorcade that followed carried not only the president and his wife Jacqueline, but Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Texas Governor John Connally and their spouses, aides, and Secret Service agents. The route was public. Crowds lined the streets. Some admired Kennedy; others despised him. Still, the appearance went forward.

At 12:30 p.m., as the motorcade turned from Houston Street onto Elm Street at Dealey Plaza, shots rang out. Two bullets struck the president—one through the throat and another fatally through the back of the head. Governor Connally was also wounded. Chaos erupted. The limousine filled with blood and confusion as it raced to Parkland Memorial Hospital, arriving just six minutes later.

Kennedy was technically alive when he reached Parkland, though doctors immediately understood the truth. His injuries were catastrophic. Jackie Kennedy never left his side. Blood-covered, silent, resolute, she followed the stretcher, refused sedation, and demanded to be present when her husband died. When the neurosurgeon told her the wound was fatal, she already knew. At 1:00 p.m., President John F. Kennedy was pronounced dead.

From that moment on, Jackie Kennedy became the central force in what followed. She would not leave Dallas without her husband. She would not allow strangers to take control of his body. And she would not permit what she saw as grotesque pageantry to replace human grief.

Removing Kennedy’s body from Dallas became an immediate priority, but Texas law required an autopsy in the county where the homicide occurred. Dr. Earl Rose, the Dallas medical examiner, insisted on following the law. Federal agents insisted on returning the president to Washington. What followed was a literal standoff in the hospital hallway, with armed officers, Secret Service agents, and aides prepared to physically intervene. Ultimately, the casket was forced out of Parkland under improvised paperwork and quiet threats, a moment that would later fuel conspiracy theories for decades.

The casket itself became a symbol of everything that went wrong. Ordered in haste, it was a massive, double-walled bronze model weighing more than 400 pounds—nearly impossible to maneuver and completely impractical. Plastic and rubber were layered inside to prevent leakage from the president’s severe head wound. Even then, it failed.

Transporting the body proved disastrous. The casket was damaged being torn from the hearse. Hinges cracked. Handles bent. It barely fit aboard Air Force One, where seats were removed to accommodate it. Jackie Kennedy stood beside Lyndon Johnson as he was sworn in as president, still wearing bloodstained clothing she refused to change. The nation watched, unaware of the chaos unfolding just feet away.

When the plane landed at Andrews Air Force Base, further humiliation followed. The lift meant to lower the casket was too short. The damaged coffin had to be awkwardly manhandled as reporters looked on. A journalist later described the scene as grotesque. Jackie insisted the body be transported by ambulance, driven by the same agent who had been behind the wheel in Dallas—a gesture of forgiveness that deeply affected him.

Behind all of this was a quieter revolution. Just months earlier, Jessica Mitford’s book The American Way of Death had ignited national outrage against the funeral industry, accusing it of exploiting grief through expensive, theatrical practices. The book had circulated within the Kennedy circle. Jackie and Robert Kennedy were deeply suspicious of funeral directors, embalming, and open-casket spectacle. They wanted simplicity, privacy, and dignity.

Yet reality intervened. Kennedy’s injuries required extensive reconstruction. Military doctors could not do that work. A prestigious Washington funeral home—Joseph Gawler’s Sons—was brought in despite the family’s objections. Overnight, embalmers rebuilt the president’s shattered skull with plaster and cotton, whispering instructions as they worked. By morning, they had created something recognizable, but unsettling. Those who saw the body described it as waxen, artificial, and deeply wrong.

The question of an open casket nearly tore the family apart. Jackie refused. Robert Kennedy and others argued that the president belonged to the people. In a tense confrontation, Jackie insisted that the public should remember her husband alive, not reconstructed. When Robert finally viewed the body himself, he understood. The casket was closed.

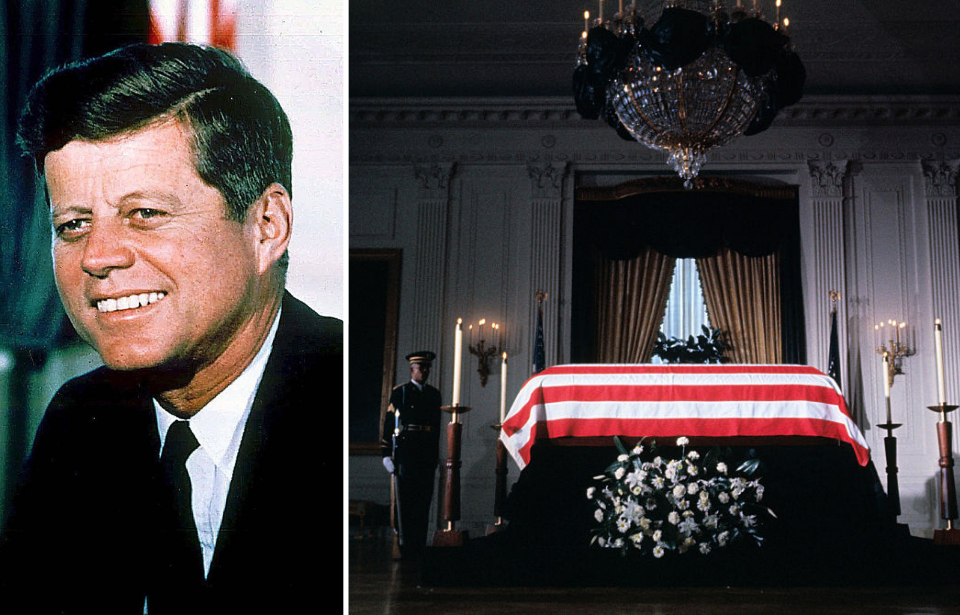

For the lying in state and funeral, Jackie struck a careful balance. She allowed national ceremony—the caisson, the eternal flame, Arlington Cemetery—but retained absolute control over her husband’s body. The coffin remained closed. Ritual replaced spectacle. Grief replaced performance.

In the end, the original bronze casket became an embarrassment no one wanted. The government paid for it, then quietly destroyed it. In 1966, it was weighted with sandbags and dropped into the Atlantic Ocean, erased from history.

The legacy of those days extends far beyond a funeral. They marked a turning point in how Americans view death, grief, and authority. The assassination exposed the brutality beneath polished tradition and accelerated a reckoning with the funeral industry that still shapes practices today.

Kennedy’s death did not just end a presidency. It shattered illusions—about safety, ceremony, and control—and forced a nation to confront death not as pageantry, but as something raw, chaotic, and deeply human.

News

Channing Tatum reveals severe shoulder injury, ‘hard’ hospitalization

Channing Tatum has long been known as one of Hollywood’s most physically capable stars, an actor whose career was built…

David Niven – From WW2 to Hollywood: The True Story

VIn the annals of British cinema, few names conjure the image of Debonire elegance quite like David Nan. The pencil…

1000 steel pellets crushed their Banzai Charge—Japanese soldiers were petrified with terror

11:57 p.m. August 21st, 1942. Captain John Hetlinger crouched behind a muddy ridge on Guadal Canal, watching shadowy figures move…

Japanese Pilots Couldn’t believe a P-38 Shot Down Yamamoto’s Plane From 400 Miles..Until They Saw It

April 18th, 1943, 435 miles from Henderson Field, Guadal Canal, Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto, architect of Pearl Harbor, commander of the…

His B-25 Caught FIRE Before the Target — He Didn’t Pull Up

August 18th, 1943, 200 ft above the Bismar Sea, a B-25 Mitchell streams fire from its left engine, Nel fuel…

The Watchmaker Who Sabotaged Thousands of German Bomb Detonators Without Being Noticed

In a cramped factory somewhere in Nazi occupied Europe between 1942 and 1945, over 2,000 bombs left the production line…

End of content

No more pages to load