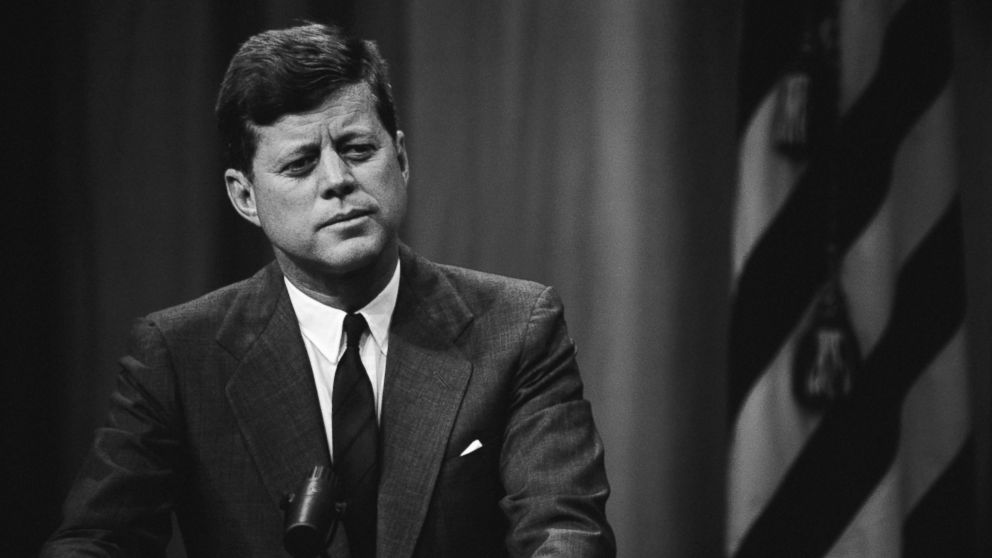

November 25, 1963. The Capitol Rotunda stood hushed beneath its towering dome as Americans filed past the flag-draped coffin of President John F. Kennedy. Among them was a familiar but subdued figure: Richard Nixon, former vice president, recent political loser, and the man whose career had been defined by his rivalry with the fallen president. Nixon wore the appropriate expression of national mourning, yet beneath it churned emotions far more complicated than grief alone.

Kennedy’s assassination had stunned the country, but for Nixon it also carried a private shock. The man who had defeated him in the closest presidential election of the century was gone — not through debate, not through votes, but through violence that rendered political rivalry meaningless. For years, Kennedy had been Nixon’s measuring stick, his obsession, his wound. Now, that rivalry ended in a way Nixon could never have imagined or prepared for.

Their story stretched back to 1947, when both entered Congress as ambitious young veterans from opposite parties. Nixon built his reputation as a fierce anti-communist investigator. Kennedy carved a quieter path, focusing on foreign policy and labor issues. They were not friends, but they were not enemies either — just rising politicians watching each other with professional curiosity.

Everything changed in 1960. The presidential race transformed mutual awareness into deep personal competition. Nixon, the experienced vice president, believed he had earned the White House through hard work and knowledge. Kennedy, younger and less seasoned, brought glamour, wealth, and a magnetic presence that captivated television audiences. When Kennedy narrowly won, Nixon accepted defeat publicly, but privately he felt robbed — by media bias, by political machines, and by a style-over-substance culture that seemed to reward charm over preparation.

That loss never left him. It festered into resentment and self-doubt, shaping how he saw politics and himself. Kennedy appeared effortless; Nixon felt he had to claw for every inch. Kennedy inspired; Nixon argued. Kennedy was admired; Nixon demanded respect. The contrast haunted him.

Yet Nixon also felt something harder to admit: admiration. Kennedy possessed instincts Nixon lacked — a natural ability to connect emotionally, to project confidence without visible strain. Even Nixon’s harshest criticisms could not erase the recognition that Kennedy had political gifts that could not be learned.

By 1963, Nixon’s career seemed over. He had lost a California governor’s race and declared to reporters they would not “have Nixon to kick around anymore.” Kennedy, meanwhile, looked set for re-election. The future belonged to Camelot.

Then Dallas happened.

When Nixon heard the news, he was genuinely shaken. Whatever bitterness lingered from 1960 dissolved in the face of national tragedy. He called to offer condolences and publicly praised Kennedy’s service. Still, as he stood in line at the Rotunda, another truth quietly formed: history had reopened doors he thought forever closed.

In the years after Kennedy’s death, Nixon spoke about him with growing nuance. He acknowledged Kennedy’s courage on civil rights and his steady leadership during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Privately, he admitted Kennedy had been a more instinctive politician, someone who understood the emotional side of leadership in ways Nixon never fully grasped.

But Nixon could never stop comparing. Kennedy’s presidency, frozen in time, remained youthful and idealized. Nixon’s would unfold under relentless scrutiny, burdened by war, protests, and distrust. Where Kennedy symbolized promise, Nixon often symbolized tension. The contrast deepened Nixon’s insecurities.

Had Kennedy lived, Nixon’s path might have vanished entirely. A two-term Kennedy presidency would have reshaped the political landscape, perhaps leaving no opening for Nixon in 1968. Instead, Kennedy’s death created both opportunity and an impossible standard. Nixon could win elections, but he could never inherit the affection Kennedy inspired.

This tension followed him into the White House. Nixon achieved major foreign policy breakthroughs — opening relations with China, negotiating arms control with the Soviet Union — yet he remained obsessed with being seen as second-rate. He wanted not just success, but admiration. That hunger fed the paranoia and secrecy that eventually erupted in Watergate.

Years later, long after his resignation, Nixon finally gave voice to the truth he had wrestled with since 1960. Reflecting on Kennedy, he said simply, “He had magic. I never had it.” The remark was not self-pitying so much as resigned. Nixon understood that politics was not only about policies or intellect. It was about connection — the ability to make people feel part of something larger.

Kennedy’s strength had been inspiration. Nixon’s was endurance. One made people dream; the other made them calculate. In a democracy, both matter, but history tends to remember the dreamers with more warmth.

Standing in the Rotunda in 1963, Nixon could not have known how deeply that comparison would shape his future. Kennedy’s death did not free him from rivalry; it made the rivalry permanent and unwinnable. Kennedy would remain forever young, forever promising. Nixon would age in public, fight visible battles, and ultimately fall.

In the end, Nixon’s most honest assessment of his rival was also an admission about himself. Competence had carried him far, but he knew it was not the same as inspiration. And the absence of that elusive “magic” would haunt him long after the competition itself was over.

News

The Death Of JFK Jr: Is The Kennedy Curse Real?

John F. Kennedy Jr. entered the world as American royalty. Born just weeks after his father won the presidency, he…

LEE HARVEY OSWALD: CIA AGENT IN THE SOVIET UNION?

On October 31, 1959, a 19-year-old former U.S. Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald walked into the American Embassy in Moscow…

🎧 Who REALLY Killed JFK? The Case Files They Hid For 60 Years

In the autumn of 1960, while cameras captured the polished image of a rising political star, a very different scene…

Did LBJ Kill JFK? Part Two – The Cover-up

In the chaotic hours following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the official story began forming almost as quickly…

✝️ Pope Leo XIV Shakes The World: He Eliminates Eleven Sacred Ceremonies!

A dramatic narrative has been circulating online, claiming that a newly reigning pope has issued an unprecedented decree abolishing numerous…

CHECK YOUR CUPBOARD! — 6 ITEMS THAT STOP THE ENEMY IN DARKNESS | Pope Leo XIV Teachings Today

Across social media platforms and online religious communities, a dramatic message has been gaining traction, delivered in the tone of…

End of content

No more pages to load