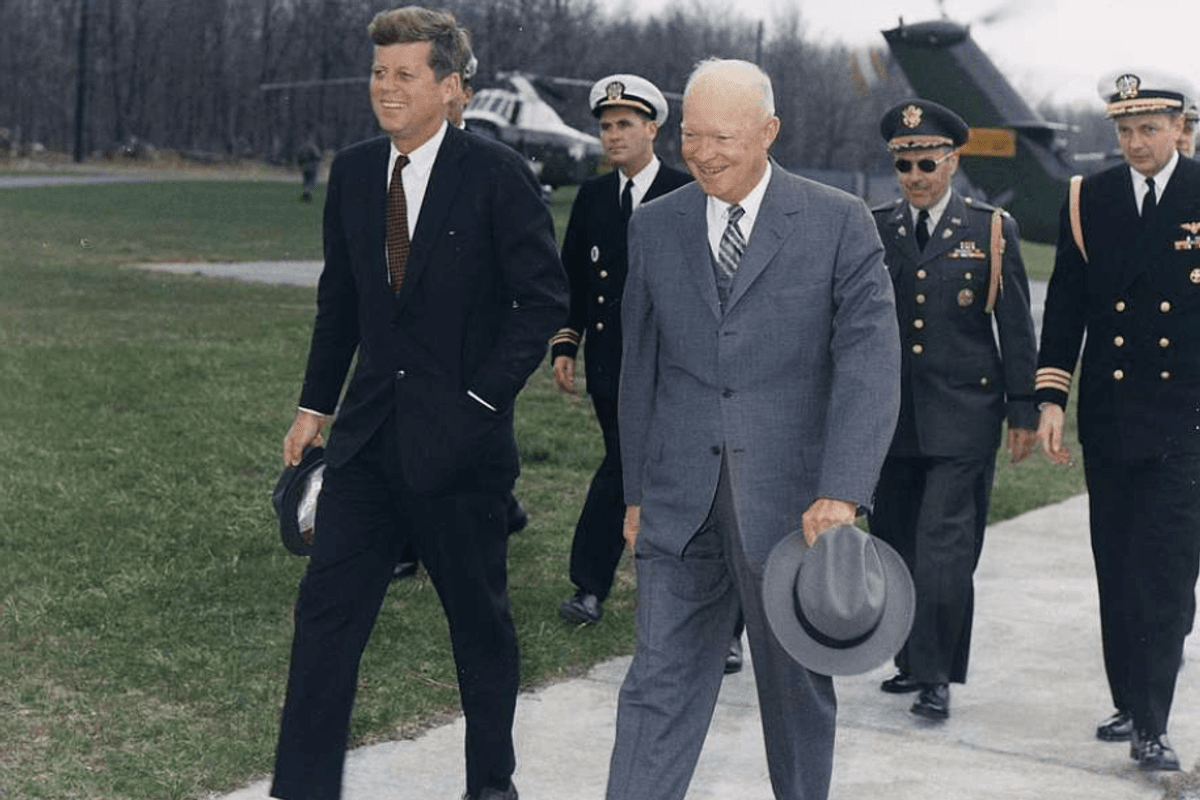

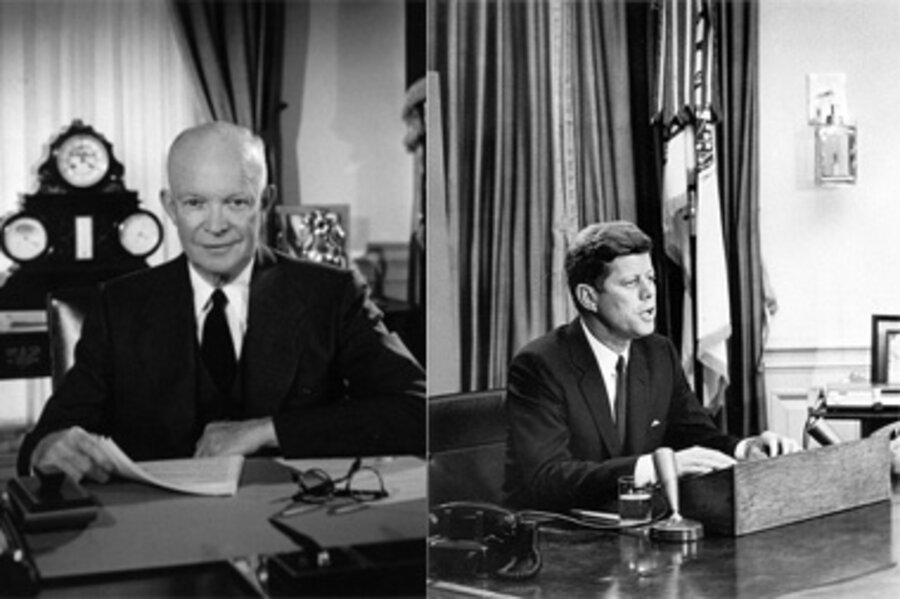

On November 22, 1963, Dwight David Eisenhower was far from Washington, far from power, and far from the noise of politics.

At seventy-three years old, the former president was living quietly on his farm near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, filling his days with painting, writing, and the calm routines of retirement.

He had commanded armies, shaped global alliances, and guided the United States through the most dangerous years of the Cold War.

That afternoon, he expected nothing more dramatic than another ordinary Friday.

Instead, a phone call would confront him with a truth about leadership that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

When Eisenhower’s longtime aide, Brigadier General Robert Schultz, informed him that President John F.

Kennedy had been shot in Dallas, Eisenhower immediately turned on the television.

Like millions of Americans, he watched the fragmented reports unfold, sensing before confirmation arrived that history had taken a catastrophic turn.

When the official announcement of Kennedy’s death was made, those in the room later recalled Eisenhower falling into a long, heavy silence.

He did not speak at first.

He simply stared at the screen, then rose and walked toward the window overlooking his land.

What had been attacked, he reportedly said, was not only a man—but the presidency itself.

That distinction mattered deeply to Eisenhower.

He understood, perhaps better than anyone alive, that the presidency was not just a job or a political prize.

It was an institution carrying the weight of national survival.

In that moment, his military instincts took over.

He immediately sought confirmation that the country was secure, that no broader attack was underway, that nuclear forces remained under control.

Assassination, to Eisenhower, was not merely murder—it was a destabilizing act with potentially global consequences.

The tragedy also reopened unresolved tensions between Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Their relationship had always been complicated.

Eisenhower had left office reluctantly in 1961, forced out by term limits, while Kennedy arrived young, ambitious, and openly critical of his predecessor.

During the 1960 campaign, Kennedy had attacked Eisenhower’s record, accusing his administration of allowing a “missile gap” and mishandling Cuba.

Eisenhower, a man who had dedicated his life to national service, felt those criticisms deeply.

He privately believed Kennedy was unprepared for the burdens of the presidency.

Their final meeting on inauguration day had been formal but cold.

Eisenhower briefed Kennedy on Laos, Berlin, Cuba, and nuclear strategy, then departed believing the country was entering uncertain hands.

When the Bay of Pigs invasion failed months later, tensions only worsened.

Though the plan had originated under Eisenhower, Kennedy bore the consequences—and behind the scenes, blame flowed both ways.

Yet by 1963, something had changed.

Kennedy had reached out to Eisenhower for advice, particularly during negotiations surrounding nuclear test bans.

Eisenhower had watched Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis with quiet admiration.

Faced with the possibility of nuclear annihilation, Kennedy had shown restraint and judgment.

Eisenhower began to recognize qualities he had once doubted.

The two men were scheduled to meet again later that month to discuss Vietnam.

That meeting never came.

As the news from Dallas settled in, Eisenhower felt more than shock.

He felt regret.

According to family members and later oral histories, he reflected on Kennedy’s growth as a leader and on how abruptly that growth had been cut short.

He began to question whether he had been too distant, too critical, too silent when his voice might have mattered.

This regret was not merely personal—it was generational.

Eisenhower had watched political extremism grow during his later years in office.

He had been labeled a traitor, a communist, an enemy by fringe groups.

After leaving office, he observed similar forces targeting Kennedy with increasing ferocity, especially over civil rights and Cold War policy.

Eisenhower had largely dismissed these voices as marginal.

Now, he wondered whether ignoring them had been a mistake.

The day after the assassination, Eisenhower wrote a deeply emotional letter to Jacqueline Kennedy.

Known for his reserve, he nevertheless expressed admiration for Kennedy’s courage and admitted that, in recent months, he had come to respect Kennedy’s judgment and dedication to peace.

The letter carried an unmistakable undertone of apology—an acknowledgment that praise offered too late is still a form of failure.

Behind the scenes, Eisenhower moved quickly to stabilize the nation.

Newly sworn-in President Lyndon B.

Johnson needed bipartisan support, and Eisenhower provided it without hesitation.

In a phone call that left Johnson visibly relieved, Eisenhower pledged his full backing and encouraged national unity.

He understood that in moments of crisis, partisanship must yield to constitutional continuity.

Eisenhower also supported the creation of the Warren Commission.

While he was not a member, his counsel carried enormous weight.

He recognized the delicate balance required—investigating thoroughly while preventing prolonged instability.

Absolute certainty, he knew, was rare in such events.

But prolonged doubt could corrode democracy itself.

As the days passed, Eisenhower’s grief deepened into reflection.

At Kennedy’s funeral, witnesses observed rare emotion on the former general’s face.

When asked later what he had been mourning, Eisenhower reportedly replied that he was grieving for the country.

It was a telling statement.

Kennedy’s death symbolized more than loss; it marked a rupture in American confidence, a moment when political violence shattered the illusion of stability.

In the years that followed, Eisenhower spoke more forcefully against extremism and political hatred.

He warned that democracy could not survive if opponents were treated as enemies.

He publicly supported policies Kennedy had championed, including nuclear arms control, and spoke more sympathetically about civil rights efforts.

Those close to him believed this was Eisenhower’s way of making amends—not only to Kennedy, but to the office they had both held.

Near the end of his life, Eisenhower admitted to his grandson that he wished he had been more supportive of Kennedy while he had the chance.

It was a quiet confession, but a powerful one.

The man who had commanded millions in war acknowledged that leadership also demands generosity, patience, and restraint—especially toward those who inherit the same burdens.

Eisenhower died in 1969, having witnessed the unraveling trust that followed Kennedy’s assassination.

He understood that when Americans lose faith in their leaders, they risk losing faith in democracy itself.

His reaction to November 22, 1963 stands as a warning and a lesson: criticism is necessary in a free society, but contempt is corrosive.

When leaders fall, the damage extends far beyond one life.

It touches the very foundations of democratic governance.

News

The Hitman’s Fingerprint: Was LBJ’s Man on the 6th Floor? (Mac Wallace)

On November 22, 1963, investigators processing the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository collected numerous pieces of physical…

Why Did JFK’s Driver Slow Down After Shots Were Fired?

At 12:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade entered Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, and within…

Did LBJ Kill JFK? Part One – The Lead up

For more than half a century, one of the most debated chapters in American political history has remained a battleground…

JFK’s Granddaughter Tatiana Schlossberg Funeral, Mother Caroline Kennedy Tribute Is STUNNING!

The final days of December carried a weight no family, no matter how strong or resilient, can ever truly prepare…

Every Woman Robert Kennedy Had an Affair With

In photographs from the 1950s and 60s, Ethel Kennedy looks like the picture of American political grace. She stands beside…

Harry EMBARRASSES Himself in Court as His Legal Team WALKS OUT Mid-Trial

It was meant to be a defining chapter in Prince Harry’s long and very public battle with the British tabloid…

End of content

No more pages to load