In a cramped factory somewhere in Nazi occupied Europe between 1942 and 1945, over 2,000 bombs left the production line with a fatal flaw that no German inspector ever detected.

These weren’t accidental defects.

They were deliberate acts of sabotage carefully orchestrated by a single man whose hands had spent decades perfecting the art of precision.

Hinrich Miller was a watchmaker by trade, a master of gears and springs, a craftsman who understood that sometimes the smallest adjustment could mean the difference between life and death.

But here’s what makes this story almost impossible to believe.

He wasn’t caught, not once, not even suspected.

While Nazi officers walked the factory floor while his fellow workers assembled weapons that would kill Allied soldiers, Hinrich was quietly ensuring that thousands of those weapons would never detonate.

The question that should be burning in your mind right now is simple.

How did he do it? How does one man sabotage an entire weapons production facility under the watchful eyes of a regime that executed people for far less and walk away without leaving a trace? By the end of this video, you’re going to understand not just the mechanics of Heinrich’s sabotage, but the psychological warfare he waged every single day.

You’ll discover the specific technique he used that was so subtle, so ingenious that even today, military historians marvel at its elegance.

You’ll learn about the narrow escapes, the close calls that should have ended his life, and the ultimate price he paid for his silent resistance.

This isn’t just another World War II story.

This is about a man who turned his greatest skill into his most dangerous weapon and in doing so saved lives without firing a single shot.

The Allies never knew his name.

The Germans never suspected his loyalty, but his work spoke louder than any propaganda poster or battlefield victory ever could.

Europe in 1942 was a continent under the boot.

The Nazi war machine had rolled across Poland, France, the Low Countries, and was pushing deep into the Soviet Union.

In occupied territories, factories that once produced watches, bicycles, and household goods were converted overnight into weapons production facilities.

The Germans were efficient, brutal, and thorough in their exploitation of conquered lands.

Every able-bodied person was put to work, feeding the Third Reich’s appetite for munitions, vehicles, and armaments.

Resistance took many forms.

Some fought with guns in the forests.

Some printed illegal newspapers, and some, like Heinrich, chose a different path entirely.

The atmosphere in these converted factories was suffocating.

Armed guards patrolled constantly.

Production quotas were ruthlessly enforced.

Quality inspectors checked every component with Germanic precision.

One mistake, one suspicious action, one whispered word of disscent could mean immediate arrest.

torture at Gestapo headquarters or a one-way trip to a concentration camp.

This was the world Hinrich inhabited every single day, a world where survival meant keeping your head down and your mouth shut.

Hinrich Müller was 53 years old when the occupation began.

He had spent 35 years as a master watchmaker in a small shop that his father had opened before the First World War.

His hands knew the language of tiny mechanisms, the delicate dance of springs and escapements, the precise tension required to make a time piece tick for decades without failure.

He was a quiet man, never political, never outspoken.

He had a wife named Greta and two grown daughters who had married and moved to other cities before the war.

When the Nazis commandeered his shop and reassigned him to a munitions factory 30 km away, he didn’t protest.

He simply reported as ordered, carrying with him the only things that mattered, his jeweler’s loop, his precision tools, and a burning, unspoken rage that he would never let show on his face.

To his new overseers, he was just another skilled worker, valuable for his steady hands and attention to detail.

They had no idea they had just recruited their own sabotur.

The factory was a former textile mill.

Its high ceilings now filled with the smell of machine oil and explosive compounds instead of cotton and dye.

Hundreds of workers moved between stations in carefully choreographed shifts.

Heinrich was assigned to the detonator assembly line where timing mechanisms were fitted into artillery shells and aerial bombs.

It was precision work that required exactly the kind of skills he possessed.

The detonators were simple in concept, but demanding in execution.

A spring-loaded firing pin, a clockwork delay mechanism, and a percussion cap that would ignite the main explosive charge.

Every component had to meet exact specifications.

Too tight and the mechanism would jam.

Too loose and it might detonate prematurely, killing the soldiers handling it.

The margin for error was measured in fractions of a millimeter.

For most workers, this was terrifying responsibility.

For Heinrich, it was opportunity.

He understood immediately that the same precision required to make these devices work could be used to make them fail, and fail in ways that would never be detected until it was far too late.

The genius of Heinrich’s plan was its simplicity and its invisibility.

He didn’t remove components or damage anything in obvious ways.

Instead, he made microscopic adjustments to the tension springs in the timing mechanisms, weakening them just enough that they would fail under battlefield conditions, but pass every factory inspection.

He used his jeweler’s tools to create hairline fractures in firing pins that would break on impact instead of striking the percussion cap.

He applied the thinnest possible coating of oil to surfaces that needed to remain dry, ensuring that over time in the heat and vibration of transport and deployment, the mechanisms would seize.

Each act of sabotage took only seconds, performed with the same focused concentration he had once used to repair expensive pocket watches.

To anyone watching, he was simply a meticulous craftsman doing his job with German efficiency.

But Hinrich knew the truth.

Every bomb that left his station carried within it the seeds of its own failure, a silent promise that it would never fulfill its deadly purpose.

The transformation of Heinrich’s life from peaceful craftsman to covert sabotur didn’t happen overnight.

And it didn’t happen because of some dramatic moment of revelation.

It was gradual, built from a thousand small humiliations and horrors that accumulated like dust until he could no longer breathe without feeling the weight of complicity.

In the first weeks at the factory he told himself he was just surviving, that keeping his head down and doing his assigned work was the smart choice, the only choice for a man his age with a wife depending on his wages.

But then came the day in late October of 1942 when a transport truck arrived at the factory gates, and Hinrich watched from a high window as 30 workers were loaded into it like cargo.

Someone whispered that they were Jews being sent east, though everyone knew what east really meant.

One of them was a young man named David Rosenberg, who had worked two stations down from Heinrich, a violin maker before the war, another craftsman of precision and patience.

Hinrich had shared his lunch bread with David twice.

Now David was gone, and Heinrich understood with perfect clarity that neutrality was a luxury he could no longer afford.

The incident that truly ignited Hinrich’s resistance came 3 weeks later, and it involved his own supervisor, Klaus Bergman.

Bergman was a German civilian, not SS, but he wore his Nazi party pin with the pride of a true believer.

He was a large man with a red face and hands like hammers, promoted to his position not because of technical knowledge but because of political reliability.

One afternoon, Bergman noticed that a young Polish woman named Katazina had assembled only 73 detonators instead of her quotota of 80.

She was 17 years old, thin as a rail, and her hands shook from hunger.

Bergman didn’t ask for explanations.

He simply walked her off the factory floor and when she returned 30 minutes later, her face was bruised and she couldn’t make eye contact with anyone.

The message was clear.

Production quotas were sacred and human beings were replaceable parts in the machine.

Hinrich went home that night and didn’t sleep.

He sat at his kitchen table, his watchmaker’s tools spread before him, and made a decision that would define the rest of his life.

If he was going to be forced to build weapons for the Reich, then he would build them in such a way that they would fail.

He would become a ghost in the machine, invisible, but deadly to the Nazi war effort.

The risks Hinrich faced were almost incomprehensible to anyone who didn’t live under occupation.

The Gestapo had informants everywhere, often people you trusted, sometimes even family members who had been threatened or bought.

Workers in munitions factories were subject to random searches, both of their persons and their workstations.

Security protocols required that any defective component be reported immediately, traced back to its source, and investigated.

The penalty for sabotage wasn’t just death.

It was torture first to extract the names of accompllices, followed by public execution designed to terrorize others into compliance.

Hinrich knew of a man in a neighboring factory who had been caught deliberately damaging rifle barrels.

The Gestapo had hung him from a lamp post in the town square and left his body there for 3 days.

His wife and children were sent to a concentration camp.

This was the context in which Hinrich operated, the suffocating reality that made every act of sabotage a potential death sentence.

But Hinrich had advantages that others didn’t.

His age made him seem harmless.

His skills made him valuable, and his quiet demeanor meant that no one paid him much attention.

He was invisible in the way that competent older workers often are, trusted to do his job and left alone.

The factory operated on a rigid schedule that Hinrich quickly memorized and exploited.

Morning shift began at 6:00 with workers filing through security checkpoints where guards checked lunch pales and occasionally performed random patowns.

The detonator assembly line ran continuously with quality inspections conducted every 2 hours by German technicians who tested sample units from each batch.

These inspectors were thorough but predictable, always checking the same specifications, firing pin alignment, spring tension within acceptable ranges and proper seating of percussion caps.

Heinrich realized that the inspections were designed to catch gross manufacturing errors, not subtle sabotage.

The tolerances were broad enough that he could work within them while still compromising functionality.

He began to study the inspection patterns, noting which inspector worked which shift, how many samples they typically tested, and what they looked for.

He discovered that the afternoon inspector, a older German engineer named Verer, had failing eyesight and relied heavily on mechanical gauges rather than visual inspection.

This became Heinrich’s primary window of opportunity.

The actual technique Hinrich developed was a masterpiece of invisible destruction.

For the spring mechanisms, he would use his precision tools to stretch the metal just beyond its elastic limit.

A change measured in microns that was impossible to detect without specialized equipment the factory didn’t possess.

The spring would pass all tension tests because it was still within acceptable range.

But the molecular structure of the metal had been compromised.

Under battlefield conditions, with temperature variations, vibration from transport, and the shock of being fired from artillery, these weakened springs would fail catastrophically.

For firing pins, he employed an even more elegant solution.

He would create microscopic stress fractures using a technique he had learned from years of working with delicate watch components.

By applying precise pressure at specific angles, he could introduce flaws that would only propagate under impact, causing the pin to shatter instead of strike.

The detonators would function perfectly in testing, pass every inspection, be loaded into bombs and shells, shipped to the front lines, and only then, when German soldiers needed the most, would they reveal their fatal flaw.

It was sabotage with a time delay, and it was virtually undetectable.

Hinrich’s double life required a level of psychological discipline that would have broken most men within weeks.

Every morning he would kiss Greta goodbye, walk the 3 km to the factory gates, and transform himself into a different person entirely.

The Hinrich who entered that facility was subservient, efficient, and utterly unremarkable.

He laughed at Klaus Bergman’s crude jokes.

He nodded respectfully when German officers toured the production floor.

He maintained friendships with other workers without ever revealing his true activities because trust was a luxury that could get everyone killed.

The mental compartmentalization was exhausting.

At his workstation, his hands moved with practiced efficiency, assembling detonators at exactly the rate expected of him, never too fast to draw attention, never too slow to invite scrutiny.

But inside each proper assembly, hidden within components that looked perfect to every inspection, was his secret rebellion.

The contradiction ate at him.

He was simultaneously the model worker and the facto’s greatest threat, and the only way to survive was to never let the mask slip, not even for a second.

The physical toll was equally brutal.

Hinrich suffered from constant tension headaches that no amount of sleep could cure.

His hands, which had once been steady enough to repair the most delicate pocket watches, now trembled when he was alone.

He developed an ulcer from the stress, a burning pain in his gut, that he treated with nothing more than bread soaked in milk, because seeing a doctor would mean questions he couldn’t answer.

Greta noticed the changes in him, but attributed them to the general misery of occupation life.

She didn’t know that her husband was committing acts of sabotage that, if discovered, would result in both their deaths.

Hinrich had made the deliberate choice never to tell her, not because he didn’t trust her, but because he loved her too much to make her complicit.

If the Gustapo ever came, he wanted her to be able to truthfully say she knew nothing.

This isolation, this inability to share the burden with the person closest to him, was perhaps the crulest aspect of his resistance.

He carried the weight of his actions entirely alone, and it was crushing him slowly, day by day, detonator by detonator.

The scope of Hinrich’s sabotage expanded gradually as his confidence grew, and his techniques became more refined.

In the first month, he compromised perhaps 20 or 30 detonators, working cautiously, testing the limits of what he could accomplish without detection.

But as weeks turned into months and no alarms were raised, no investigations launched, he became bolder.

By the spring of 1943, he was sabotaging virtually every detonator that passed through his hands, sometimes as many as 15 or 20 per shift.

The mathematics of his resistance were staggering.

If he worked 5 days a week and compromised an average of 12 detonators per day, that meant 60 per week, roughly 240 per month, nearly 3,000 per year.

Over the course of 2 and 1/2 years, the numbers climbed into the thousands.

Each sabotage detonator represented a bomb that wouldn’t explode, an artillery shell that wouldn’t detonate, ordinance that would fail at the crucial moment when German forces needed it.

Hinrich had no way of knowing the impact of his work, no intelligence reports or battlefield assessments, but he understood the basic logic.

Every weapon he rendered useless was a weapon that couldn’t kill allied soldiers, couldn’t destroy cities, couldn’t extend the war.

He was fighting the Third Reich with fractions of millimeters and microns of metal fatigue, and he was winning his small, invisible war.

The close calls were inevitable and terrifying.

The first serious scare came in April of 1943 when a batch of artillery shells failed during a training exercise somewhere on the Eastern Front.

The failure rate was noticed and an investigation was ordered.

For 2 weeks, the factory was paralyzed by inspections.

Gustapo officers interviewed workers, examined production records, and subjected random detonators to destructive testing.

Hinrich continued working with his usual efficiency, showing no sign of concern, while inside his chest, his heart hammered against his ribs like it was trying to escape.

The investigation ultimately blamed the failures on a batch of substandard springs from a supplier, and the supplier was punished, while Hinrich remained untouched.

But the experience taught him that he was never truly safe, that every day could be the day his luck ran out.

Another close call came when Klaus Bergman, in a rare moment of actual supervision, stood directly behind Hinrich for nearly 15 minutes watching him work.

Hinrich’s hands remained perfectly steady as he assembled detonators with textbook precision, even as sweat ran down his spine.

Bergman eventually walked away satisfied, never knowing that the detonator Hinrich had just completed was already fatally compromised.

The psychological strategy that kept Hinrich alive was his absolute commitment to appearing ordinary.

He never spoke about politics, never voiced opinions about the war, never did anything that might mark him as either a fervent Nazi supporter or a potential dissident.

He existed in a carefully maintained neutral zone, the kind of person who draws no attention because there’s nothing interesting about them.

He was old, reliable, skilled, and boring.

When other workers whispered about Allied victories or German defeats, Hinrich said nothing.

When propaganda posters went up celebrating Nazi achievements, he nodded along with everyone else.

When air raid sirens sent everyone to shelters, he followed procedures exactly.

This performance of normaly was its own form of resistance, a protective camouflage that allowed him to continue his real work.

Hinrich understood that heroes in wartime don’t announce themselves, don’t seek recognition or glory.

They simply do what must be done in silence and shadow and pray they survive long enough to see the world they’re fighting for.

Every night when he returned home to Greta, he was one day closer to liberation and one day closer to discovery, walking a tightroppe suspended over an abyss with nothing but his wits and his watchmakaker’s precision to keep him balanced.

By the summer of 1943, Heinrich had developed his sabotage into something approaching an art form with multiple techniques he could deploy depending on the specific type of detonator being assembled.

For impact fuses used in artillery shells, he would manipulate the firing pin striking surface, creating microscopic irregularities that reduce the force of impact just enough to prevent reliable ignition.

For timed fuses in aerial bombs, he would subtly alter the escapement mechanism in the clockwork delay, introducing friction points that would cause the timing to fail unpredictably.

His most ingenious innovation involved the percussion caps themselves.

Using a technique borrowed from his watchmaking days, he would apply the faintest trace of oil to the primer compound, an amount so small it was invisible to the naked eye and wouldn’t prevent the cap from passing inspection tests.

But over time, during storage and transport, that oil would migrate and contaminate the explosive material, rendering it inert when the moment of truth arrived.

Each method had been carefully tested in his mind, refined through observation, and executed with the same meticulous attention to detail he had once reserved for repairing heirloom time pieces.

Hinrich wasn’t just sabotaging weapons.

He was engineering failure with the precision of a master craftsman, and every successful detonator that left his hands was actually a monument to his invisible rebellion.

The factory itself had become a strange kind of theater, where everyone played their assigned roles, while hidden dramas unfolded beneath the surface.

Workers shuffled between stations, faces blank with exhaustion and fear, going through motions that had become mechanical and mindless.

The German supervisors strutted with authority they exercised arbitrarily, sometimes benevolent, often cruel, always unpredictable.

The armed guards watched everything with bored vigilance, ready to respond to infractions with violence, but rarely attentive enough to notice what actually mattered.

And Hinrich moved through this landscape like a ghost, his presence so familiar, it had become invisible.

He had learned to read the rhythms of the factory the way he once read the tick of a watch.

understanding when attention was focused elsewhere, when inspectors were rushing to meet quotas, when guards were changing shifts and creating brief windows of opportunity.

He knew which workers could be trusted to look the other way if they noticed something irregular, not because they were part of his resistance, but because they had their own survival to worry about, and asking questions was dangerous.

The factory had taught everyone that ignorance was safer than knowledge, and Heinrich exploited that collective willful blindness ruthlessly.

The toll on Hinrich’s conscience was perhaps the most unexpected burden of his secret war.

At night, lying beside Greta while she slept, he would replay the day’s work in his mind, and confront uncomfortable questions that had no easy answers.

How many German soldiers would die because of bombs that failed to explode? Not all of them were Nazis.

Many were conscripts, boys barely old enough to shave, forced into service just as the factory workers were forced to build weapons.

When a detonator he had sabotaged failed in battle, would it save Allied lives or simply prolong a firefight, leading to more casualties on both sides? He wrestled with the mathematics of morality, trying to calculate whether the lives saved by weapons that didn’t work out weighed the potential complications his sabotage might cause.

But ultimately, Heinrich always arrived at the same conclusion.

The Nazi war machine was an engine of genocide and conquest, and anything that weakened it, even fractionally, was justified.

The Vermach wasn’t defending Germany.

It was prosecuting a war of annihilation across Europe.

And every bomb that failed to detonate was one less tool in that machinery of death.

He couldn’t save everyone.

Couldn’t stop the war single-handedly.

But he could do this one thing, and so he continued, carrying the weight of those moral calculations like stones in his pockets.

The autumn of 1943 brought a development that both terrified and validated Hinrich’s work.

Rumors began circulating about equipment failures on the Eastern Front.

These weren’t official announcements, of course, but whispers passed between workers.

Fragments of conversations overheard when German officers thought no one was listening.

artillery shells that didn’t explode.

Bombs dropped from Luftvafa planes that failed to detonate.

Munitions that malfunctioned at critical moments during Soviet counter offensives.

The rumors were vague enough that Hinrich couldn’t know for certain whether his sabotage was responsible, but the timing aligned perfectly with when detonators from his factory would have reached the front lines.

He felt a strange mixture of pride and terror.

Pride because it meant his work was having real impact, that he wasn’t just engaging in symbolic resistance, but actually degrading the Nazi war effort.

Terror because increased equipment failures meant increased scrutiny, more investigations, a higher chance of discovery.

The Gestaper would be asking questions, examining records, looking for patterns.

Hinrich knew he needed to be more careful than ever to vary his techniques to ensure that failures appeared random rather than systematic.

He couldn’t afford to leave a signature that some sharp-eyed investigator might recognize.

The winter of that year tested Hinrich in ways he hadn’t anticipated.

Food shortages worsened throughout the occupied territories, and factory rations were cut to near starvation levels.

Workers began collapsing at their stations from hunger and exhaustion.

The cold was brutal, and the facto’s heating was minimal, conserving fuel for the war effort.

Heinrich’s hands, which needed to remain steady and precise for his sabotage work, grew stiff and clumsy in the freezing temperatures.

He developed chilllanes on his fingers that made even simple tasks painful.

Yet, production quotas remained unchanged, and the pressure to meet them intensified.

Klaus Bergman began conducting more frequent inspections.

his frustration at the workforce’s declining productivity, manifesting in arbitrary punishments and public humiliations.

Three workers were shot in the courtyard that winter for crimes that ranged from theft of factory materials to suspicion of sabotage, though none of them had actually been saboturs.

Hinrich watched these executions from his station window, his face carefully neutral, his hands continuing their work without pause.

Each execution was a reminder that death was always one mistake away, one moment of carelessness, one stroke of bad luck.

But it also hardened his resolve.

The men who had been killed were innocent, murdered by a regime that valued weapons production over human life.

If Hinrich was going to risk everything, if he was potentially going to die for resistance, then he would make every risk count, sabotage every detonator he could reach, and fight this invisible war.

until liberation came or his luck finally ran out.

The spring of 1944 marked a turning point both in the war and in Hinrich’s psychological state.

Allied bombing raids were increasing in frequency and intensity, targeting factories, rail lines, and supply routes across occupied Europe.

The factory where Heinrich worked had been hit twice, though neither strike caused catastrophic damage.

The raids brought a strange comfort to Hinrich.

Every bomb that fell on German infrastructure was a reminder that liberation was coming, that his silent resistance was part of a larger struggle that was slowly, inexurably turning against the Third Reich.

But the raids also brought new complications.

Damaged facilities meant production delays, which meant increased pressure from Berlin, which meant more supervision, more inspections, more opportunities for discovery.

The factory operated under constant tension now with air raid sirens interrupting shifts multiple times per week.

Workers would rush to shelters, production would halt, and when the allclear sounded, everyone would return to stations and work even harder to make up for lost time.

In the chaos and pressure of these disruptions, Hinrich found new opportunities.

Rushed inspections were sloppy inspections, and exhausted supervisors cut corners.

He increased his sabotage rate, sometimes compromising 20 detonators in a single shift, working with an urgency born from the growing certainty that the war was entering its final phase.

The relationship between Heinrich and his fellow workers had evolved into something complex and unspoken.

He wasn’t the only one engaged in small acts of resistance.

Others found their own ways to undermine production.

Some work deliberately slowly, stretching tasks to reduce output.

Others feigned incompetence, producing defective components that would be caught and scrapped.

A young woman named Anna, who assembled fuse housings, had developed a technique of introducing metal shavings into threading, causing components to seize during assembly at later stages.

None of these resistors ever spoke directly about what they were doing.

The risk of informance was too great, but they recognized each other through subtle signals, a knowing glance when production numbers came up short, a slight nod when a batch was rejected for quality issues.

Hinrich and Anna never exchanged a word about their activities, but they had a silent understanding, a mutual respect between saboturs who knew the price of their actions.

This invisible network of resistance gave Heinrich a sense of solidarity he hadn’t felt since the occupation began.

He wasn’t alone in his fight.

Even if he fought alone, others were waging the same war from their own stations with their own methods.

All of them bound by the shared knowledge that they were choosing conscience over survival.

The mental calculations Hinrich performed became increasingly sophisticated.

As his experience grew, he began to think strategically about which types of detonators to prioritize for sabotage based on their likely deployment.

Detonators destined for anti-tank shells received his most aggressive treatment because those weapons were being used against Soviet armor on the Eastern Front, and Hinrich had heard enough whispers to know that the Red Army was pushing the Vermach back mile by bloody mile.

Detonators for aerial bombs received subtler sabotage because those might be used against civilian targets, and Hinrich wanted them to fail absolutely, not partially.

He developed a mental taxonomy of destruction, categorizing his work by strategic value.

Artillery shells bound for defensive positions received less attention than those marked for offensive operations.

It was all guesswork based on incomplete information and overheard fragments of conversation.

But Heinrich felt compelled to make these distinctions.

If he was going to spend his life on this work, if he was going to risk everything, then he wanted to maximize the impact.

Every choice mattered, every detonator was a decision, and Hinrich approached each one with the same thoughtful consideration he had once brought to restoring antique time pieces.

The personal cost of Hinrich’s resistance had become undeniable by the summer of 1944.

He had aged a decade in 2 years.

his hair gone completely white, his face carved with lines of stress and sleepless nights.

The ulcer had worsened to the point where he could barely eat solid food, surviving on thin soups and bread.

His hands, despite the continued precision of his work, achd constantly from the strain of manipulating tiny components in cold conditions.

Greta had stopped asking questions about his health, because his answers were always the same evasions, but her worried eyes followed him around their small apartment.

She knew something was wrong beyond the general misery of occupation, but Hinrich’s silence was impenetrable.

The isolation was perhaps the worst of it.

Carrying this enormous secret, performing this dangerous work, and having no one to share the burden with, no one to acknowledge what he was doing or why it mattered.

Hinrich sometimes wondered if he would survive to see liberation, and if he did, whether he would ever be able to tell anyone what he had done.

Would there be records? Would Allied intelligence ever discover the sabotage detonators and trace them back to their source? Or would his resistance die with him, unknown and unacknowledged, just another forgotten act of defiance in a war filled with millions of them? By August of 1944, the reality of impending defeat was becoming impossible for even the most fervent Nazis to deny.

The Allies had landed in Normandy.

The Red Army was advancing relentlessly from the east and the strategic situation for Germany was catastrophic.

In the factory, production quotas became increasingly frantic and unrealistic as the Reich demanded more weapons to stem the tide of losses.

Klaus Bergman, sensing the approaching end of Nazi power, became erratic and dangerous, lashing out at workers with sudden violence as if brutality could somehow reverse the course of history.

Henrik watched this deterioration with grim satisfaction tempered by fear.

The endgame was approaching, but cornered animals were the most dangerous, and a collapsing regime might lash out in final desperate purges.

Hinrich needed to survive just a little longer to maintain his cover through these final chaotic months to see the liberation he had been working toward.

The detonators continued to flow through his hands, and his sabotage continued unabated.

But now, every day felt like a countdown.

Every shift a gamble that his luck would hold for just one more sunrise, one more act of resistance, one more small victory in his invisible war against the machine that had consumed his world.

The autumn of 1944 brought a new and unexpected danger that threatened everything Heinrich had built.

The factory received a visit from a special SS technical inspection unit, elite engineers, whose sole purpose was to investigate the increasing reports of munitions failures across multiple fronts.

These weren’t the regular inspectors who checked samples and signed off on production quotas.

These were specialists with advanced testing equipment, forensic training, and absolute authority to halt production and conduct investigations.

They arrived without warning on a cold October morning.

Six men in immaculate SS uniforms carrying cases of instruments that Hinrich had never seen before.

The factory floor fell silent as they set up their testing station in the center of the production area.

A deliberate placement designed to intimidate and observe.

Hinrich felt his stomach drop as he watched them unpack precision measuring devices, microscopes with magnification far beyond what the factory normally used, and chemical testing kits.

For the first time since beginning his sabotage, he faced the real possibility that his techniques might be detected, that the invisible flaws he had so carefully engineered might suddenly become visible under this level of scrutiny.

He continued working, maintaining his usual steady pace, but every nerve in his body screamed danger.

The inspection lasted 5 days, and they were the longest days of Hinrich’s life.

The SS engineers pulled random samples from every stage of production, including finished detonators from the quality approved stockpile ready for shipment.

They subjected these components to destructive testing, disassembling them completely, examining every part under high-powered microscopes, measuring spring tensions with calibrated instruments, and analyzing metal composition with chemical tests.

Heinrich watched from his station as they worked, his hands continuing to assemble detonators with practice efficiency, while his mind raced through scenarios.

Had he left any detectable pattern? Were his microscopic alterations visible under their advanced equipment? Would they notice the subtle oil contamination on percussion caps? The lead inspector was a thin man with wire- rimmed glasses named Sturm Ban Fura Fischer, and he approached his work with the same methodical precision that Hinrich brought to his sabotage.

Fischer interviewed workers randomly, asking technical questions about procedures, checking their knowledge against actual practice.

When he reached Hinrich’s station, he stood silently for several minutes, watching the older man’s hands move through the assembly process.

Hinrich’s pulse hammered in his ears, but his hands remained steady, his face showing nothing but mild curiosity about the inspection.

Fisher asked three questions about spring tension specifications, proper firing pin alignment, and quality control procedures.

Heinrich answered each one perfectly, reciting the official standards with the boring accuracy of a competent technician who had repeated these tasks thousands of times.

Fischer made a note in his ledger and moved on.

On the third day of the inspection, disaster nearly struck.

Fischer’s team discovered abnormalities in a batch of detonators that had been assembled 2 weeks earlier during a period when Hinrich had been particularly aggressive in his sabotage.

The spring tensions in six units from that batch measured at the very bottom edge of acceptable tolerances suspicious enough to warrant further investigation.

Faircher ordered the entire batch quarantined and demanded production records showing who had worked on those units during that shift.

Hinrich’s name was on the list along with three other assemblers who had been stationed on the detonator line that day.

The four workers were called into a small office for individual interviews, while Gustapo officers stood by, their presence a silent threat.

Hinrich was interviewed third after two terrified younger men who had emerged pale and shaking.

When his turn came, he entered the office with the shuffling gate of a tired old man, his expression showing nothing but weary compliance.

Fischer sat behind a desk, Hinrich’s personnel file open in front of him, and asked about the specific shift in question.

Hinrich explained that he remembered the day because there had been an air raid warning that had disrupted production, forcing them to evacuate midshift and return to stations in a hurry.

The rushed conditions, he suggested carefully, might have led to less careful spring tension calibration across all four assemblers work.

It was a plausible explanation, one that spread potential blame rather than concentrating it, and Fischer seemed to accept it.

After 20 minutes of questions, Hinrich was dismissed with a warning about maintaining standards regardless of conditions.

The inspection concluded on the fifth day with a report that Hinrich never saw, but heard about through the usual channels of factory gossip.

Fischer’s team had found quality control issues that they attributed to inadequate supervision, rushed production schedules, and insufficient training of workers.

Klaus Bergman was reprimanded.

Three workers were transferred to different facilities, and new inspection protocols were implemented, but no sabotage was detected, no conspiracy uncovered, no arrests made.

The SS engineers packed their equipment and departed, leaving behind tighter procedures that would make Hinrich’s work more difficult, but not impossible.

He had survived the most dangerous 5 days of his secret war, but the experience had shaken him deeply.

That night, he sat at his kitchen table long after Greta had gone to bed, his watchmaker’s tools spread before him, his hands finally allowing themselves to tremble.

He had come within inches of discovery, of torture, of execution.

The smart thing would be to stop, to cease his sabotage, and simply survive until liberation came.

But Heinrich knew he wouldn’t stop.

Couldn’t stop.

The SS inspection had proven that his techniques worked, that even expert analysis with advanced equipment couldn’t definitively detect his sabotage.

If anything, that validation made him more determined to continue.

The final months of 1944 brought both hope and horror.

Allied advances were undeniable now.

Even German radio couldn’t completely obscure the reality of retreating forces and lost territory.

In the factory, production became increasingly chaotic as supply lines fractured and raw materials grew scarce.

There were days when certain components simply didn’t arrive, halting production entirely.

These days brought frantic demands to work double shifts to make up for shortfalls.

The guards became more nervous and trigger-happy, shooting two workers in November for infractions that months earlier would have earned only beatings.

Klaus Bergman disappeared for a week and returned drunk, ranting about betrayal and weakness, his authority crumbling along with the Reich he served.

Hinrich navigated this deteriorating situation with the same careful neutrality he had maintained throughout.

But internally, he felt the approaching end like a physical sensation.

Liberation was coming, possibly within months, and he needed to survive just a little longer.

His sabotage continued without pause, perhaps more important now than ever, as desperate German forces tried to mount last ditch defenses with increasingly unreliable equipment.

Every detonator that failed was one less obstacle to Allied advance, one less threat to the soldiers fighting to free Europe.

Hinrich was no longer just resisting.

He was actively contributing to victory.

And that knowledge sustained him through the cold, hungry, terrifying final winter of the war.

The winter of 1944 into 45 was the coldest anyone could remember, and it brought suffering that transcended the already miserable conditions of occupation.

The facto’s heating system failed completely in January, and there was no fuel to repair it.

Workers assembled detonators with fingers so numb they could barely feel the components they handled.

Their breath visible in clouds, ice forming on metal surfaces overnight.

Heinrich’s arthritis, which had been manageable before, now flared with savage intensity, turning every movement of his hands into an exercise in controlled agony.

Yet this physical torment became perversely an advantage for his sabotage.

The other workers frozen, clumsy hands, produced naturally defective work at an increased rate, providing cover for Heinrich’s deliberate flaws.

Quality control inspectors themselves freezing and miserable, rushed through checks just to get back to whatever meager warmth they could find.

Production numbers fell across the board, and in the chaos of systemic failure, Heinrich’s systematic sabotage became even more invisible.

He pushed himself harder than ever, working through pain that would have sent him home in peace time because he understood that these final months were critical.

The Vermacht was making its last desperate stands.

The Battle of the Bulge had just been fought in the Arden, and every weapon that failed now might be the difference between a successful Allied advance and a stalled offensive that would prolong the war.

By February of 1945, the factory itself was falling apart in ways that mirrored the collapse of the Third Reich.

Allied bombing had intensified to the point where raids came almost daily, sometimes multiple times per day.

The production floor was pockmarked with hastily repaired damage from near misses and shrapnel.

Entire sections of the building had been cordoned off as structurally unsound.

Supply deliveries became sporadic and unreliable.

Sometimes raw materials would arrive.

Other times nothing.

The workforce had been decimated by conscription, disease, starvation, and the occasional execution, dropping from over 400 workers at the occupation’s peak to barely 200 struggling souls.

Klaus Bergman had essentially given up any pretense of leadership, spending most of his time in his office, drinking schnaps and raging at phantom enemies.

The guards, sensing the approaching end, were more interested in securing their own escapes than in forcing discipline.

In this environment of comprehensive breakdown, Heinrich operated with a freedom he had never experienced before.

No one was watching closely anymore.

No one cared about production quotas when the front lines were collapsing.

He sabotaged openly now, not even bothering with his most subtle techniques, sometimes simply omitting critical components entirely, knowing that inspections had become purely performative gestures.

The moment Hinrich had been working toward the climax of his invisible war, came not as a single dramatic event, but as a cascading series of confirmations that his work had mattered.

In early March, a German officer visiting the factory let slip during a tirade about incompetence that an entire artillery battery on the Eastern Front had reported catastrophic ammunition failure rates exceeding 40% during a critical engagement near the Uda River.

The officer was drunk and angry, blaming factory workers for the military’s defeats.

But Heinrich heard the numbers and felt something close to joy, 40%.

That meant nearly half the shells fired hadn’t detonated, hadn’t killed Soviet soldiers, hadn’t stopped the Red Army’s advance.

Later that same week, an SS logistics officer conducting an inventory audit discovered that detonators from Heinrich’s factory, tracked by batch numbers, had been associated with unusually high failure rates across multiple theaters of operation.

The officer launched a cursory investigation.

But by this point in March of 1945, with Soviet forces less than 100 km away and American forces approaching from the west, no one had the resources or the will to pursue it seriously.

The audit was filed and forgotten, but Hinrich knew his sabotage had worked.

Thousands of Nazi weapons had failed because of him.

Lives had been saved.

Advances had succeeded where they might have been repelled.

He had fought his war with micrometers and microscopic flaws, and he had won.

The final weeks before liberation were surreal and terrifying in equal measure.

The factory continued operating on pure inertia, producing detonators that would likely never be used because the vermach was retreating on all fronts and supply lines had disintegrated.

Workers showed up not because they feared punishment, but because there was nowhere else to go, and the factory provided minimal rations.

That meant the difference between slow starvation and rapid starvation.

Hinrich continued his sabotage out of habit and principle, even though he knew these detonators would probably sit in warehouses until they were captured by Allied forces.

Klaus Bergman disappeared entirely in midappril, presumably fleeing ahead of the Soviet advance, and no one replaced him.

The guards drifted away in ones and twos, abandoning their posts to save themselves.

On April 20th, air raid sirens wailed for the final time, but no bombers came.

Instead, the distant rumble of artillery could be heard, growing steadily louder.

workers gathered in small groups, whispering about what would happen when Soviet or American troops arrived.

Would they be treated as collaborators for having worked in a munitions factory? Would the liberators understand that they had been slaves, not volunteers? Hinrich said nothing during these discussions, but privately he wondered if his sabotage would ever be discovered, if anyone would ever know what he had done.

Liberation came on April 23rd, 1945 when Soviet tanks rolled into the industrial district where the factory stood.

The remaining workers, fewer than 100 by that point, emerged from the building with raised hands, expecting either execution or imprisonment.

Instead, they were processed by Red Army officers who seemed more interested in securing the facility than in punishing its workers.

Heinrich was questioned briefly through a translator, gave his name and occupation, and was told to go home.

He walked out of the factory gates for the last time, his precious watchmaker’s tools wrapped in cloth and tucked under his arm, and made his way through rubble strewn streets toward the apartment where Greta waited.

The war in Europe would officially end in 2 weeks, but for Hinrich, it ended that day as he crossed the threshold of his home, and allowed himself finally to believe that he had survived.

He had sabotaged thousands of Nazi detonators, had waged a secret war that no one knew about, had risked everything for a cause that would likely never be acknowledged.

and he had won.

Not in the grand public way that soldiers win wars, but in the quiet invisible way that resistance operates in the shadows.

The Third Reich was defeated, and Hinrich Mueller, master watch maker and unknown sabotur, had played his small but crucial part in that defeat.

The immediate aftermath of liberation was nothing like the jubilant scenes Hinrich had imagined during the darkest days of occupation.

There were no parades, no celebrations, no sense of triumph.

Instead, there was only exhaustion, hunger, and the enormous task of surviving in a city that had been bombed into near oblivion.

The apartment Hinrich shared with Greta had survived structurally.

But there was no electricity, no running water, and no food beyond what they had managed to hide during the final chaotic weeks.

The Soviet occupiers were liberators, yes, but they were also conquerors with their own agenda, and the transition from Nazi rule to Soviet military administration was jarring and often violent.

Hinrich kept his head down, as he had learned to do so well during the occupation, and focused on the immediate concerns of finding food, repairing damage to their home, and simply making it through each day.

He said nothing to anyone about his sabotage work.

The Soviet officers conducting interviews seemed uninterested in the details of factory operations, and Hinrich saw no benefit in revealing what he had done.

His resistance had been personal, necessary for his own conscience, but he had no desire for recognition or potential complications that might arise from admitting to systematic sabotage of military production.

The physical toll of Heinrich’s secret war became fully apparent in the months following liberation.

Without the adrenaline of constant danger and the driving purpose of his sabotage, his body simply collapsed.

The ulcer that he had ignored for years perforated in June, requiring emergency surgery at a barely functioning hospital where medical supplies were scarce and conditions were medieval.

He spent 3 weeks recovering, delirious with fever for much of it, and emerged from the experience 20 lb lighter and looking like a ghost.

The arthritis in his hands, exacerbated by years of precision work in freezing conditions, had progressed to the point where his fingers were permanently curled and painful.

The irony was cruel.

He had spent decades as a master watchmaker, then years using those same skills to sabotage weapons, and now his hands were too damaged to do either.

Greta nursed him through the recovery with whatever food and medicine she could scavenge, never asking the questions that Hinrich could see in her eyes.

She knew on some level that her husband had done something during the war years beyond simple survival, something that had cost him his health and nearly his life.

But she respected his silence, understanding that some burdens were too heavy to share, even with those we love most.

The revelation of the full scope of Nazi atrocities came gradually through newspapers, radio broadcasts, and the testimonies of survivors who began returning from concentration camps.

Heinrich had known the regime was evil.

That knowledge had driven his resistance.

But the systematic industrial scale of the Holocaust exceeded anything he had imagined in his darkest moments.

The numbers were incomprehensible.

6 million Jews murdered, millions more Poles, Soviets, Roma political prisoners, disabled people, homosexuals, all fed into a machine of death that had operated in parallel with the war effort Heinrich had sabotaged.

He thought of David Rosenberg, the violin maker who had disappeared from the factory in October of 1942.

loaded onto a truck bound east.

David had almost certainly died in a camp, his craftsman’s hands that had created beauty destroyed by a regime that valued only domination and extermination.

Heinrich wrestled with a question that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Had his sabotage mattered at all in the face of such overwhelming evil, he had disabled thousands of bombs and shells, possibly saved hundreds or thousands of lives, but millions had died anyway.

Was his resistance meaningful or merely symbolic? A personal act of defiance that changed nothing in the grand calculus of the war.

By the winter of 1945 into 46, a new normal began to emerge in the shattered landscape of postwar Europe.

Heinrich, unable to return to watchmaking due to his damaged hands, found work doing simple repairs and maintenance at a local school that the Soviet administration was trying to reopen.

The pay was minimal, but it was honest work that didn’t involve weapons or deception, and that meant something to him.

He and Greta survived on rations, bartered goods, and the occasional package from Greta’s sister, who lived in a rural area less devastated by the fighting.

Life was hard, often miserable, but it was life without the constant terror of discovery and execution, and that alone felt like a luxury.

Hinrich never spoke about his sabotage.

Not to Greta, not to neighbors, not to anyone.

The factory where he had worked had been partially dismantled by Soviet forces, its equipment shipped east as war reparations, and the building itself stood empty and broken, a monument to a regime that had collapsed.

Sometimes Hinrich would walk past it during his commute to the school, and he would pause, looking at the windows where he had once stood, assembling detonators with deliberate floors, and he would allow himself a moment of quiet satisfaction.

He had survived.

He had resisted, and somewhere in battlefields across Europe, his invisible work had made a difference.

The question of whether Hinrich’s sabotage would ever be discovered or acknowledged remained unanswered for years.

No Allied intelligence service came looking for him.

No investigation traced the pattern of detonator failures back to their source.

The chaos of the wars end, the millions of displaced people, the enormous task of processing war crimes and reconstructing shattered societies meant that one old watchmaker’s secret resistance simply disappeared into the noise of history.

Heinrich made peace with that anonymity.

He had never sought recognition.

He had only sought to do what was right when confronted with absolute evil.

Whether history remembered him or not was irrelevant to the moral necessity of his actions.

He had seen what needed to be done, had possessed the skills to do it, and had accepted the risks.

That was enough.

The only record of his work existed in his own memory, in the microscopic floors he had engineered into thousands of detonators, and in the lives of soldiers who never knew they had been saved by an old man’s steady hands and unwavering conscience.

It was a legacy invisible to everyone, including those it had benefited.

But Hinrich carried it with quiet pride through the difficult years of reconstruction that followed the war’s end.

The truth about Hinrich’s sabotage emerged in the most unexpected way almost a decade after the war’s end.

In 1954, a team of American military historians conducting research for an official study on Vermachar equipment failures during the final years of the war uncovered a pattern in captured German records.

Specific batches of detonators traced through meticulous Nazi documentation that had survived the chaos of collapse showed failure rates that were statistically impossible to explain through normal manufacturing defects or material shortages.

The pattern was too consistent, too systematic, and too geographically concentrated in munitions produced at a specific factory in occupied territory.

The historians, intrigued by what appeared to be evidence of sustained sabotage, began cross-referencing production records with personnel files that Soviet authorities had turned over as part of postwar cooperation agreements.

Heinrich’s name appeared repeatedly in shift schedules corresponding to the batches with the highest failure rates.

An American researcher named Captain Robert Morrison working with a translator, arrived at Heinrich’s apartment on a gray afternoon in March, presenting credentials and asking politely if they could speak about his wartime work.

Heinrich, now 65 years old and in declining health, sat across from Morrison in his small kitchen, and for the first time since the war ended, told someone what he had done.

The interview lasted 6 hours over two days with Morrison taking detailed notes while Hinrich described his techniques, his motivations, and the psychological burden of maintaining his secret for so long.

Morrison listened with growing amazement as this elderly man with crippled hands explained the sophisticated methods he had developed to sabotage detonators in ways that would only reveal themselves under battlefield conditions.

Heinrich showed Morrison his old watchmaker’s tools, explained the physics of spring fatigue and firing pin stress fractures, and provided technical details that Morrison’s team would later verify against analysis of recovered munitions.

Morrison asked if Heinrich had kept any records, any documentation of his work, and Hinrich laughed bitterly.

Records would have been a death sentence.

Everything had existed only in his memory and his hands.

When Morrison asked why Heinrich had never come forward after the war, the answer was simple.

Who would have believed him? He was just an old factory worker, one of millions, with no proof of his claims beyond his own testimony.

Morrison assured him that the evidence in the German records provided that proof, that Hinrich’s sabotage could be verified and documented.

For the first time in nearly a decade, Hinrich allowed himself to believe that his resistance had not only mattered, but might actually be remembered.

The American military’s investigation concluded that Hinrich Müller had been responsible for sabotaging between 2,2500 detonators over approximately 30 months, making him one of the most successful individual saboturs of the Second World War.

Morrison’s report estimated that Hinrich’s work had resulted in the failure of munitions used in at least a dozen major engagements on both the eastern and western fronts, potentially saving hundreds of Allied lives and contributing to the degradation of German combat effectiveness during critical periods of the war’s final phase.

The report recommended that Heinrich be recognized for his contributions.

And in 1955, in a small ceremony at the American embassy, he was presented with a civilian citation for extraordinary service in support of Allied victory.

Greta attended, finally learning the full story of what her husband had endured and accomplished during those terrible years.

She wept as the citation was read, not from joy, but from the sudden overwhelming understanding of how close she had come to losing him, how many times he had risked execution, and how completely he had borne that burden alone to protect her.

Hinrich accepted the recognition with quiet dignity, but told Morrison afterward that the citation wasn’t why he had done it.

He had sabotaged those detonators because it was the only way he could live with himself, the only way to resist evil with the tools and skills he possessed.

The recognition brought unexpected complications along with vindication.

Some former factory workers, learning of Heinrich’s sabotage through newspaper accounts of the American citation, reacted with anger.

They argued that his actions had put everyone at risk, that if he had been caught, collective punishment might have resulted in executions beyond just his own.

Others saw him as a hero who had done what they had been too afraid to attempt.

The controversy was minor and brief, but it highlighted the moral complexities of resistance under totalitarian occupation.

Heinrich understood their anger.

He had wrestled with those same questions himself during the war.

Was individual resistance justified if it potentially endangered others? He believed it was, but he also acknowledged that others might reasonably disagree.

The debate died down within months, but it reinforced Hinrich’s original instinct to remain silent.

Recognition was complicated and sometimes painful.

The work itself had been its own justification and reward.

He had needed no external validation to know he had done the right thing, and the citation, while appreciated, changed nothing about his fundamental understanding of his wartime actions.

Hinrich Müller lived for another 8 years after receiving the American citation, passing away in 1963 at the age of 74.

His death certificate listed the cause as heart failure, but Greta knew the truth was more complex.

He had died from the accumulated toll of years spent under unbearable stress, physical deprivation, and the permanent damage to his body from wartime hardships.

In his final years, he had become something of a local figure, occasionally invited to speak at schools about the war and resistance, though he always downplayed his own role and emphasized the importance of ordinary people making moral choices in extraordinary circumstances.

He never expressed regret about his sabotage, but he also never glorified it.

War, he would tell students, was a failure of humanity, and resistance was simply what conscience demanded when confronted with evil.

His funeral was modest, attended by Greta, their daughters and grandchildren, a few neighbors, and Captain Morrison, who had stayed in touch and traveled from the United States to pay his respects.

Hinrich was buried in a small cemetery with a simple headstone that listed his name, dates, and occupation.

Watchmaker.

There was no mention of sabotage, no reference to the war, nothing to indicate that this quiet man had waged his own invisible campaign against the Third Reich.

But those who knew the truth understood that beneath that simple word, watchmaker, lay a story of extraordinary courage, technical brilliance, and moral clarity in the darkest of times.

Hinrich Müller’s story forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about heroism, morality, and the nature of resistance that remain relevant decades after his death.

We live in an age where we lionize dramatic acts of defiance, where we celebrate resistance that announces itself with flags and speeches and public declarations.

But Hinrich’s war was nothing like that.

His resistance was invisible, technical, sustained over years in complete isolation with no expectation of recognition and every expectation of execution if discovered.

He saved lives without ever meeting the people he saved.

He fought battles that left no visible scars on landscapes or monuments in town squares.

His weapon was precision.

His ammunition was patience.

And his battlefield was a workbench in a freezing factory where one wrong move, one moment of carelessness, one stroke of bad luck would have ended not just his resistance but his life.

This kind of heroism doesn’t fit our comfortable narratives about war.

It’s messy, morally complex, and profoundly lonely.

Hinrich never got to see enemy soldiers surrender because of his actions.

He never received battlefield reports confirming his impact.

He simply went to work each day, performed acts of sabotage that might or might not matter, and went home to pretend everything was normal.

That takes a kind of courage that’s harder to comprehend than charging a machine gun nest because it requires sustaining moral conviction in complete darkness with no validation, no support, and no certainty of success.

The question I want you to sit with is this.

What would you have done in Hinrich’s position? It’s easy to say from the comfort of peace that you would have resisted, that you would have fought back against evil.

But the reality Hinrich faced was infinitely more complicated.

Resistance meant risking not just your own life, but potentially the lives of everyone around you.

It meant carrying a secret so dangerous that you couldn’t share it even with your spouse.

It meant watching innocent people executed while you continued your hidden work, knowing that discovery would add your name to that list.

It meant wrestling every single day with the calculation of whether your actions actually mattered in the face of industrial-cale genocide and continental war.

Most people faced with those odds and that isolation would choose survival over resistance.

There’s no shame in that.

It’s simply human nature to prioritize staying alive.

But Hinrich chose differently, and that choice is worth examining not to judge ourselves against it, but to understand what drives certain individuals to accept unbearable risks for principles that offer no personal benefit.

He gained nothing from his sabotage except the ability to live with his conscience, and he paid for that with his health, his peace of mind, and decades of silence about the most significant thing he ever did.

The broader significance of Hinrich’s story lies in what it tells us about the actual mechanics of resistance under totalitarian regimes.

We tend to romanticize resistance movements, imagining networks of brave fighters coordinating operations and supporting each other.

Some resistance did work that way, but much of it looked like Heinrich, isolated individuals making quiet choices to undermine the system in whatever small ways their positions allowed.

the factory worker who assembled components incorrectly.

The cler who misfiled documents.

The train conductor who delayed shipments, the accountant who introduced errors into logistics records.

None of these acts were dramatic.

None generated headlines or medals.

But cumulatively they degraded the Nazi war machine in ways that are impossible to quantify but undeniably real.

Hinrich’s sabotage of 2,000 plus detonators was quantifiable because American researchers found the pattern in captured records.

But how many other acts of quiet resistance went completely undocumented, unknown even to the people who benefited from them? The real lesson here isn’t that we should all aspire to be like Heinrich, though his courage deserves respect.

The lesson is that resistance to evil doesn’t require you to be a soldier or a spy or someone with access to weapons.

It requires only that you identify what you can do within your circumstances, accept the risks, and do it consistently despite fear and isolation.

Heinrich had the skills of a watchmaker and access to detonators, so he sabotaged detonators.

Someone else might have different skills and different access, presenting different opportunities for resistance.

The common thread is the choice to act rather than collaborate, to resist rather than comply.

What haunts me most about Hinrich’s story is the silence he endured for nearly a decade after the war.

Imagine carrying that secret, that accomplishment, that burden of memory, and having no one to share it with.

Imagine the moments when doubt crept in, when he wondered if his sabotage had actually made any difference, if the risks he had taken were justified by results he could never confirm.

Hinrich died knowing his work had been documented and recognized.

But he lived most of his postwar life with only his own conscience as testimony to what he had done.

How many other Heinrichs existed, saboturs and resistors whose work was never discovered, who died without anyone knowing what they had risked and accomplished.

The historical record is full of gaps where individual acts of courage simply vanished into silence, leaving no trace except perhaps in the microscopic flaws in a bomb that failed to explode, saving lives in ways that could never be traced back to their source.

This should disturb us, not because we need every hero to be recognized, but because it reveals how much of history happens in shadows and silence.

How many people make extraordinary choices that the world never sees? Hinrich’s story survived because American researchers happened to find patterns in German records and happened to track him down while he was still alive.

How many similar stories simply evaporated because the evidence was destroyed or the protagonist died before anyone thought to ask? So, here’s what I want you to take from Hinrich Müller’s Invisible War.

Heroism isn’t always visible.

Resistance isn’t always dramatic, and the most important moral choices are often the ones no one ever knows about except the person making them.

In a world that increasingly feels polarized and unstable, where authoritarianism is rising again in various forms around the globe, Heinrich’s story reminds us that ordinary people with ordinary skills can make extraordinary differences when they choose conscience over compliance.

You don’t need to be a soldier to fight evil.

You need only to recognize evil when you see it.

Identify what tools and access you possess and then use those resources consistently to undermine rather than support the systems of oppression.

Hinrich Miller was a watchmaker who became a sabotur because that was what his circumstances demanded and his skills allowed.

What would your skills allow? What would your circumstances demand? These aren’t comfortable questions, and I don’t expect you to answer them out loud.

But I do want you to sit with them, because the distance between Hinrich’s world and our own is not as great as we might like to believe, and the choices he faced might be closer to choices we could face than any of us want to admit.

His story isn’t just history.

It’s a mirror asking us who we would be when everything is on the line, and no one is watching except our own conscience.

Remember, Hinrich Müller.

Remember that resistance can be invisible.

Remember that one person with patience and precision and unwavering moral clarity can sabotage thousands of instruments of death and walk away unknown.

And remember that the most important battles are often fought not on fields with flags and fanfare, but in silence, in shadow, in the small spaces where individual conscience meets collective evil and chooses to fight back no matter the cost.

News

His B-25 Caught FIRE Before the Target — He Didn’t Pull Up

August 18th, 1943, 200 ft above the Bismar Sea, a B-25 Mitchell streams fire from its left engine, Nel fuel…

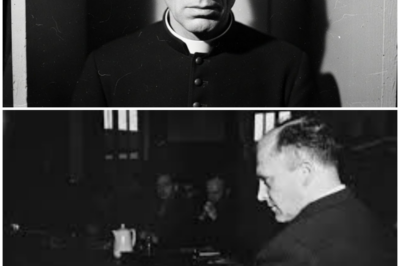

The Priest Who Recorded SS Confessions in the Booth and Sent Them to the Allies

Munich, 1943. The confessional booth of St. Mary’s Church stood in the shadows of the nave, a wooden sanctuary…

FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis Charity — $250M Terror Network & Governor ARRESTED

At 11:47 on a bitter Tuesday morning, federal agents stepped in front of the cameras in Minneapolis and delivered a…

FBI & DHS Raid Florida Sheriff Linked to Sinaloa & CJNG — 324 Guns & 2.3 Tons Seized

The promise sounded bold and uncompromising: a government determined to drain the swamp of corruption, imposing strict bans on lobbying…

BREAKING: DEA & FBI Raid Texas Logistics Hub — 52 Tons of Meth Seized

It started in the heat shimmering above the asphalt just outside San Antonio, the kind of afternoon where nothing feels…

ICE & FBI Raid Minnesota Cartel — Somali-Born Federal Judge Exposed & $18B Stolen

The moment the video surfaced, everything changed. The footage showed an ICE agent cornered amid chaos, a vehicle surging toward…

End of content

No more pages to load