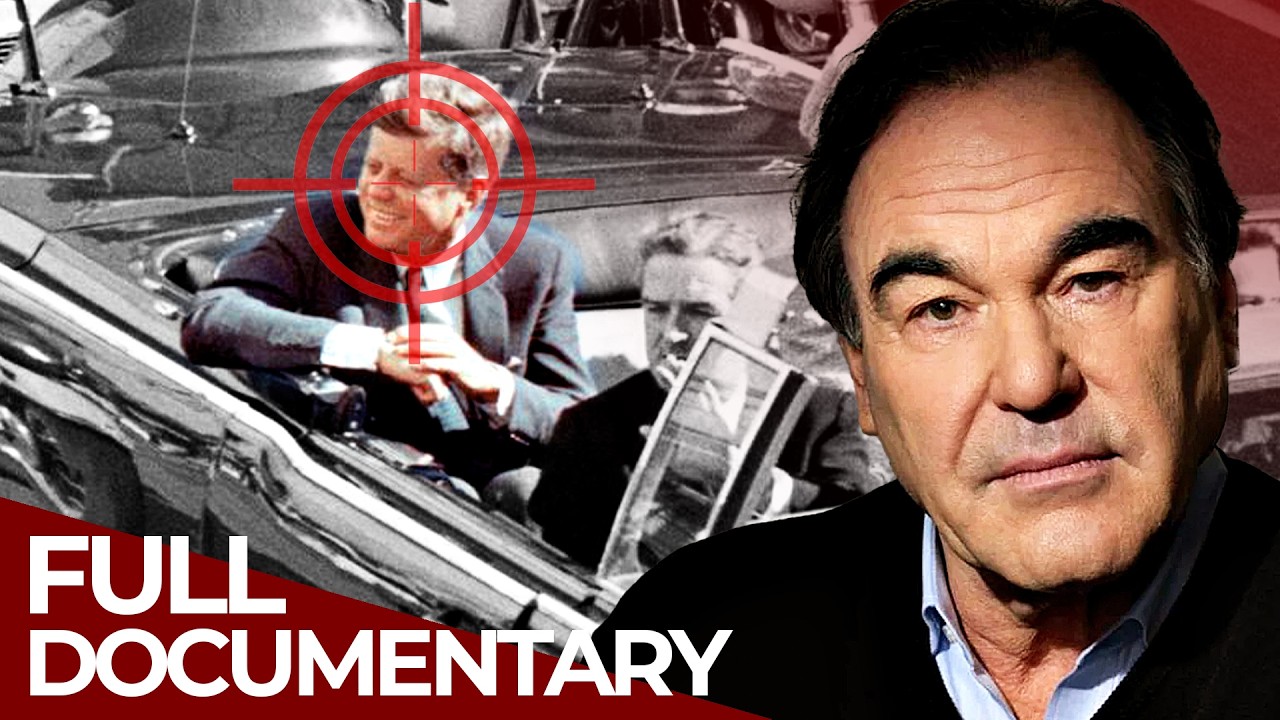

The Battle for America’s Memory: Oliver Stone, JFK, and the War Over Truth

When Oliver Stone decided to make JFK, he was fully aware that he was stepping into forbidden territory.

The assassination of President John F.

Kennedy was not just a historical event; it was a carefully sealed narrative, protected for decades by official reports, institutional authority, and a compliant media culture.

Stone did not claim to possess “the truth.

” What he challenged was something far more dangerous: the idea that the truth had already been settled.

Stone’s starting point was Jim Garrison’s book On the Trail of the Assassins, a work largely ignored by mainstream America despite its explosive claims.

To Stone, even the possibility that a fraction of Garrison’s allegations might be true was enough to warrant serious examination.

The assassination of a sitting president, he believed, was not merely a crime but a defining test of democracy itself.

If the public had been misled about such an event, then the implications went far beyond 1963.

Central to Stone’s argument is his rejection of the Warren Commission’s conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.

He does not deny the presence of facts in the official report, but he fiercely criticizes its speculative leaps, most famously the “magic bullet” theory.

For Stone, the Warren Commission represents not definitive truth, but a constructed myth—one designed to bring closure quickly and prevent deeper inquiry.

His film, he insists, is a counter-myth, not a documentary, and not a final answer.

Stone repeatedly emphasizes uncertainty.

Eyewitnesses disagreed.

Physical evidence raised unanswered questions.

Key documents were withheld.

Intelligence agencies, particularly the CIA and FBI, controlled what information reached investigators.

Perhaps most damning in Stone’s eyes was the appointment of Allen Dulles—former CIA director fired by Kennedy—to help investigate Kennedy’s death.

To Stone, this was equivalent to asking the fox to investigate the henhouse.

The filmmaker draws a sharp distinction between two conspiracies.

The first, he argues, could have been small—perhaps five to ten individuals—operating within a tightly compartmentalized, cellular structure.

In such a system, participants would not know each other’s identities, let alone the full scope of the operation.

Plausible deniability would be built into every level.

Nothing on paper.

No single mastermind visible.

The second conspiracy, Stone claims, was the cover-up.

Unlike the assassination itself, this did not require full knowledge of what truly happened.

It required only a collective willingness to accept a convenient explanation and move on.

Fear of international instability, political embarrassment, or even nuclear war may have played a role.

Silence, in this sense, became a form of consent.

Stone’s anger is particularly sharp when directed at the American media.

In his view, journalists failed their most basic duty in 1963 by accepting official statements without asking the most obvious question: why.

When global leaders are assassinated, the press typically examines motive, political enemies, and power struggles.

In Kennedy’s case, Stone argues, that curiosity vanished almost instantly.

Oswald was labeled a lone communist assassin before he was even formally charged.

When Oswald himself was killed, headlines declared him “the president’s assassin,” not the alleged assassin—a subtle but powerful shift that cemented guilt in the public mind.

Evidence that later emerged only deepened Stone’s suspicion.

The CIA maintained an extensive file on Oswald while publicly denying any significant interest in him.

Testimony contradicted internal records.

Information that might have complicated the official story remained buried for years.

To Stone, this was not merely incompetence but a pattern.

Why does this matter so deeply to him? Because Stone sees the Kennedy assassination as part of a broader history of deception.

He points to Vietnam, secret bombings in Laos and Cambodia, Watergate, Iran-Contra, and covert arms deals as documented conspiracies—proven cases in which the American public was deliberately misled by its leaders.

Against this backdrop, questioning the official JFK narrative becomes not radical paranoia, but civic responsibility.

Stone also challenges the trivialization of Kennedy himself.

Over time, Kennedy has often been reduced to a symbol of charisma, scandal, and personal flaws.

Stone argues that this distracts from what truly mattered: Kennedy’s policies.

His efforts to de-escalate the Cold War, his back-channel negotiations with the Soviet Union and Cuba, his resistance to deploying combat troops in Vietnam, and his vision of a different global order all posed a threat to entrenched interests within the national security establishment.

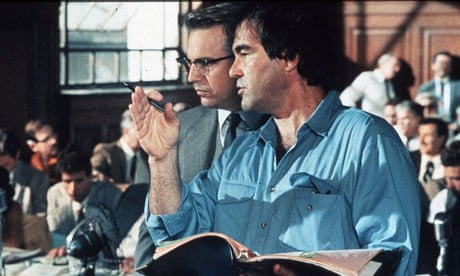

In JFK, Stone uses dramatic techniques—blending archival footage with reenactments—to immerse viewers in the atmosphere of the era.

Critics accused him of deliberately blurring fact and fiction.

Stone does not deny this.

He argues that emotional engagement was necessary to break through decades of official narrative.

A purely factual documentary, he believes, would have been ignored, just as Garrison’s book had been.

Stone rejects the accusation that his film suggests a vast, clumsy conspiracy involving everyone from the CIA to the FBI to the president himself.

Instead, he describes a minimalist model: a small operational core, followed by a much larger, often unconscious, process of institutional self-protection.

Many involved in the cover-up, he suggests, may never have known the truth—they simply sensed that something was wrong and chose silence over chaos.

Ultimately, Stone does not demand belief.

He demands doubt.

His film is not an answer, but a challenge: to reconsider what democracy means when power operates in secrecy, when narratives are manufactured, and when asking questions becomes an act of rebellion.

In that sense, JFK is less about the past than about the present—and the uneasy realization that history may not be written by those who seek truth, but by those who control its telling.

News

André Rieu’s Son Says Goodbye After His Father’s Tragic Diagnosis

Andre Rieu, the renowned Dutch violinist and conductor famously known as the “King of Waltz,” has recently been the subject…

André Rieu Says Farewell After Devastating Health Revelation

Andre Rieu, the celebrated Dutch violinist and conductor known worldwide as the “King of Waltz,” has been at the center…

Ina Garten Reveals Emotional Update About Her Childhood Abuse by Her Father

Ina Garten, known to millions as the warm and inviting host of Barefoot Contessa, is revealing a deeply personal and…

Tragic Details America’s Test Kitchen Doesn’t Want You To Know

America’s Test Kitchen has built its reputation on authenticity. Unlike many TV cooking sets, ATK boasts real kitchens with working…

Famous Chefs Who Are Totally Different Off-Screen

When you watch a celebrity chef every week, it almost feels like they’re part of your family. Their smiles, jokes,…

Ina Garten Shares Emotional Update about Split from Husband Jeffrey: ‘It Was Real Painful’

Ina Garten’s gentle adjustment of her husband Jeffrey’s appearance for a photo session is a tender moment that belies the…

End of content

No more pages to load