On November 22, 1963, investigators processing the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository collected numerous pieces of physical evidence, including latent fingerprints found on cardboard boxes near the southeast corner window—an area later described as the “sniper’s nest.

” Most of the prints were eventually attributed to Lee Harvey Oswald, who had worked in the building.

One print, however, remained unidentified for years, quietly preserved in the case files.

Decades later, that unidentified fingerprint became the focus of renewed controversy.

In the late 1990s, private researchers revisiting old evidence sought to determine whether advances in forensic comparison might finally resolve its origin.

Among those approached was A. Nathan Darby, a retired fingerprint examiner with extensive experience in law enforcement identification work.

According to accounts from researchers involved, Darby was given two sets of prints for comparison without being told their sources.

After examining ridge patterns and points of similarity, he concluded that one print matched the other beyond standard identification thresholds and signed a notarized affidavit stating his opinion.

The claim that followed was dramatic: that the unidentified print from the Depository matched that of Malcolm Everett Wallace, a Texas man with a criminal record whose name had surfaced in various assassination-related theories over the years.

Supporters of this identification argued that Wallace’s background, alleged political associations, and past legal controversies made the finding deeply significant.

Malcolm Wallace’s life story, as reconstructed by researchers and critics alike, includes a 1951 murder conviction in Texas that resulted in an unusually light sentence.

Court records confirm he was tried and convicted in a fatal shooting, though interpretations of the case differ sharply.

Some writers have portrayed Wallace as a politically connected enforcer shielded by powerful allies, while others describe the narrative as heavily embellished over time, with limited hard evidence tying him to broader criminal or political operations.

The fingerprint claim added new fuel to those suspicions.

If Wallace’s print had truly been left on a box in the so-called sniper’s nest, it would suggest his presence in a location central to the assassination.

That implication, in turn, would challenge the lone-gunman conclusion reached by the Warren Commission and later reaffirmed in various forms by official inquiries.

Yet the identification has never been universally accepted.

Other fingerprint specialists who reviewed the materials have disputed the match, arguing that the available prints were too partial or degraded for a definitive conclusion.

Forensic identification, while powerful, depends heavily on print quality and examiner interpretation.

Different analysts can reach different conclusions, especially when working from copies rather than original evidence.

The FBI and other official bodies have not endorsed the Wallace identification.

To this day, the unidentified print remains a point of disagreement rather than a settled forensic fact.

This divide highlights a broader issue that runs through the history of the Kennedy assassination: the tension between independent research claims and the cautious standards of official institutions.

The Wallace theory also intersects with longstanding debates about political power in Texas during the mid-20th century.

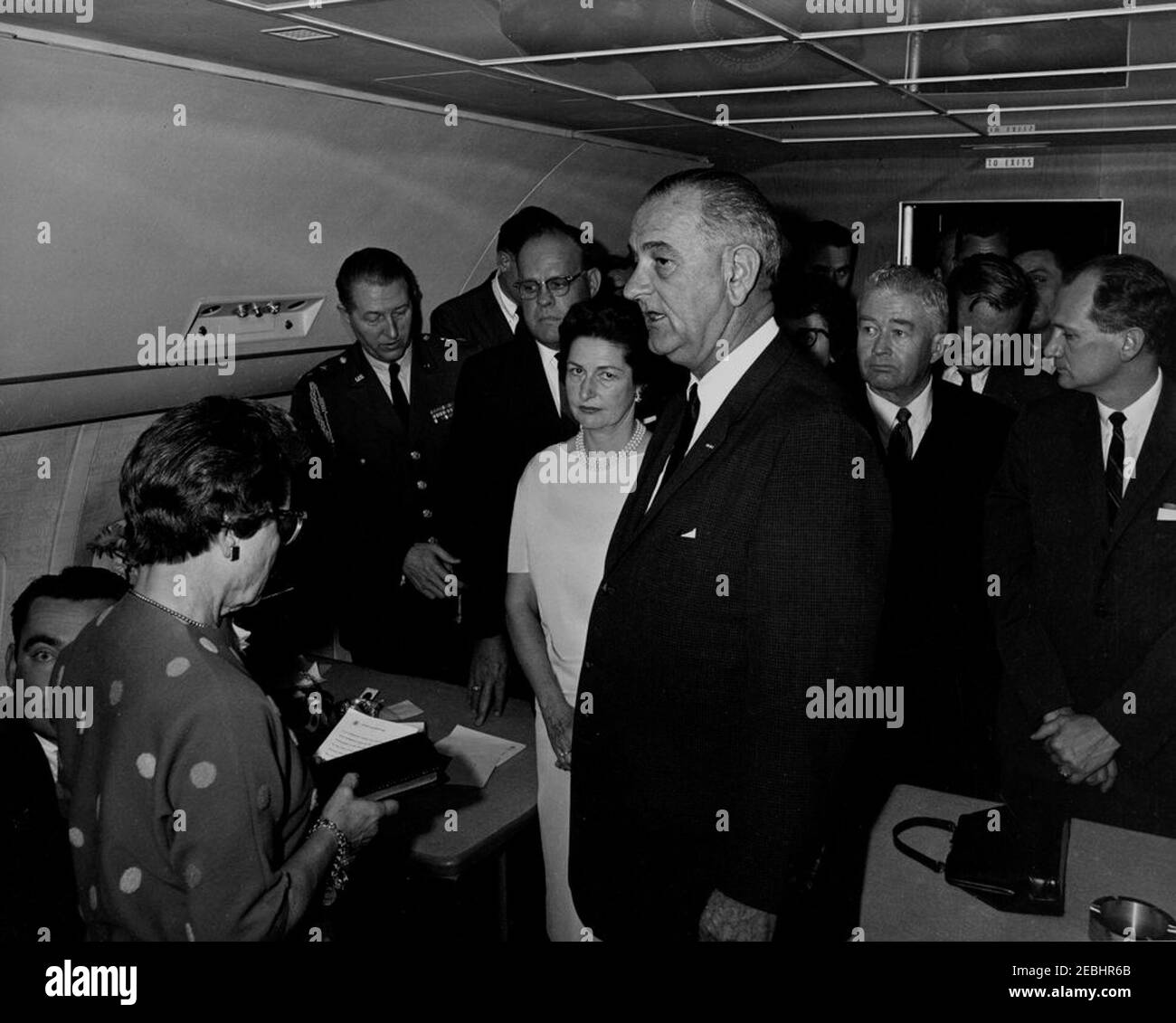

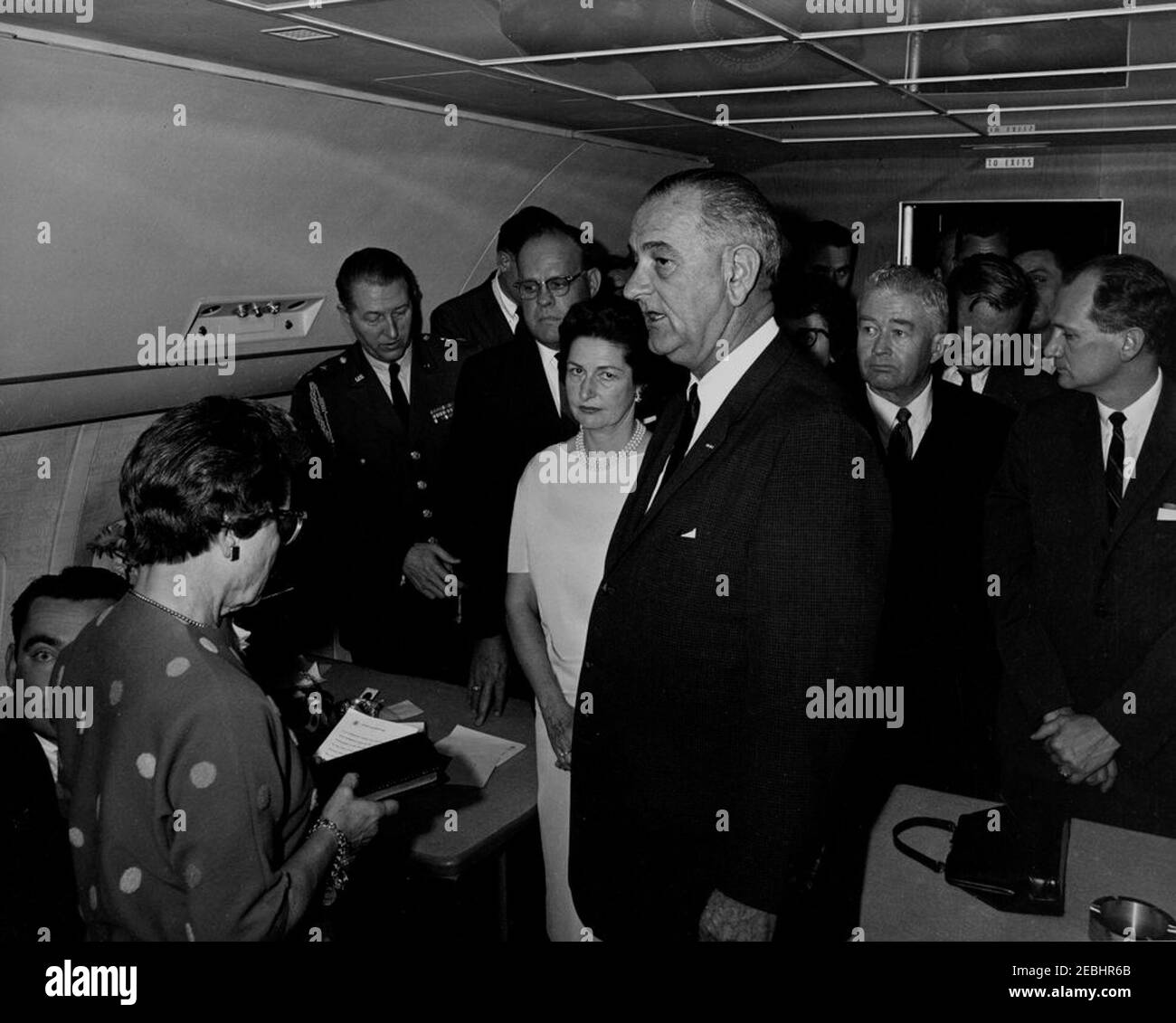

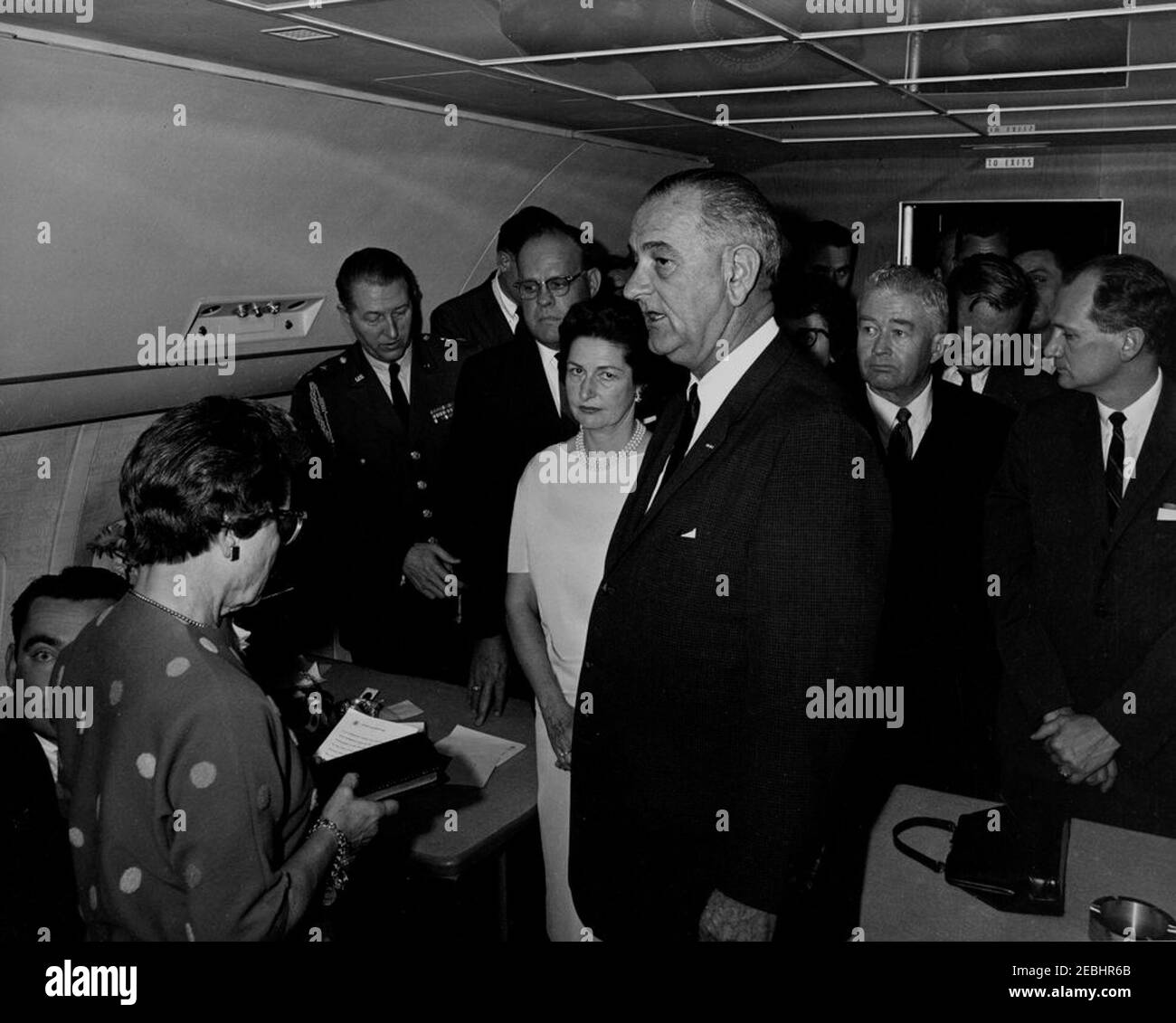

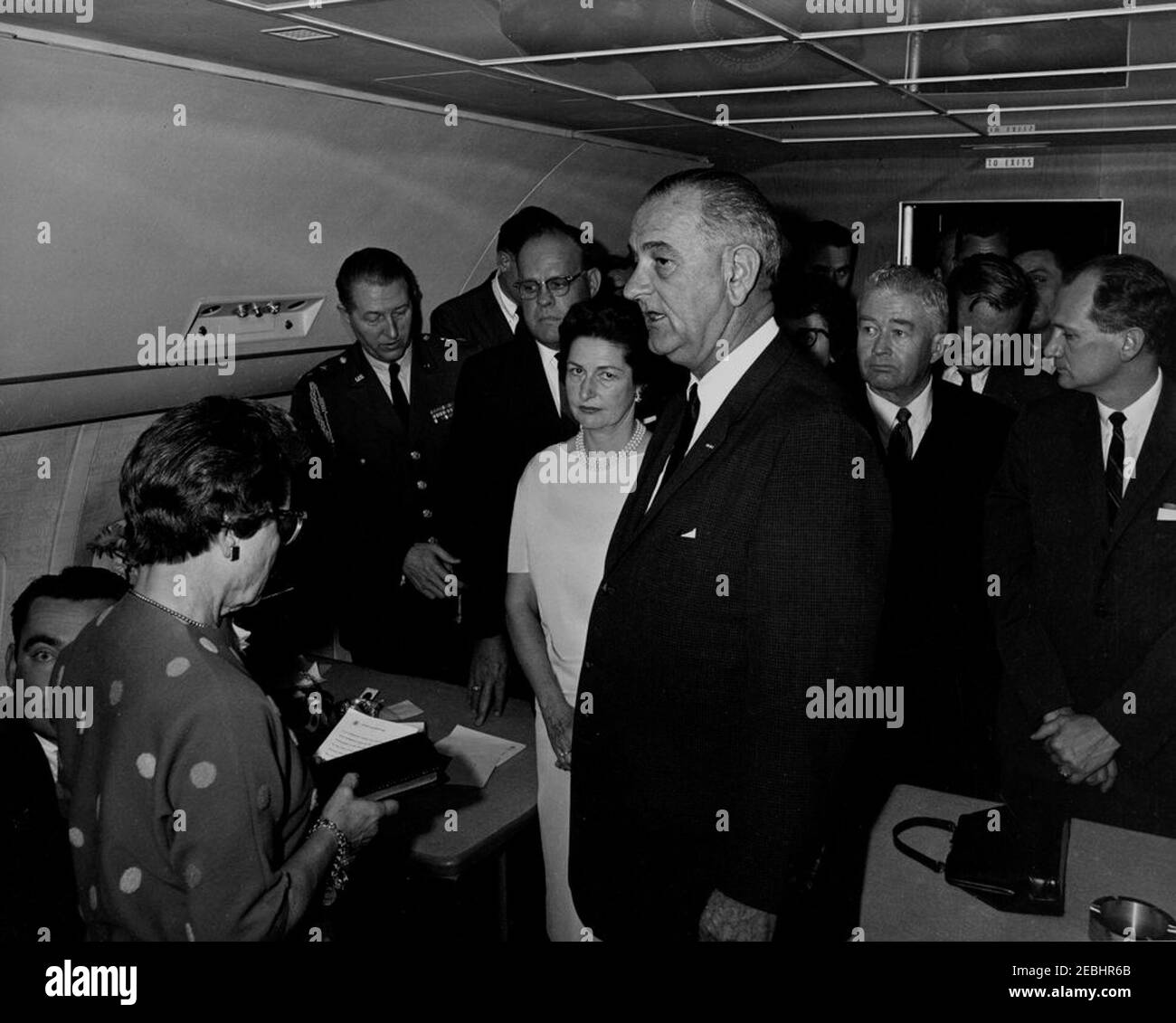

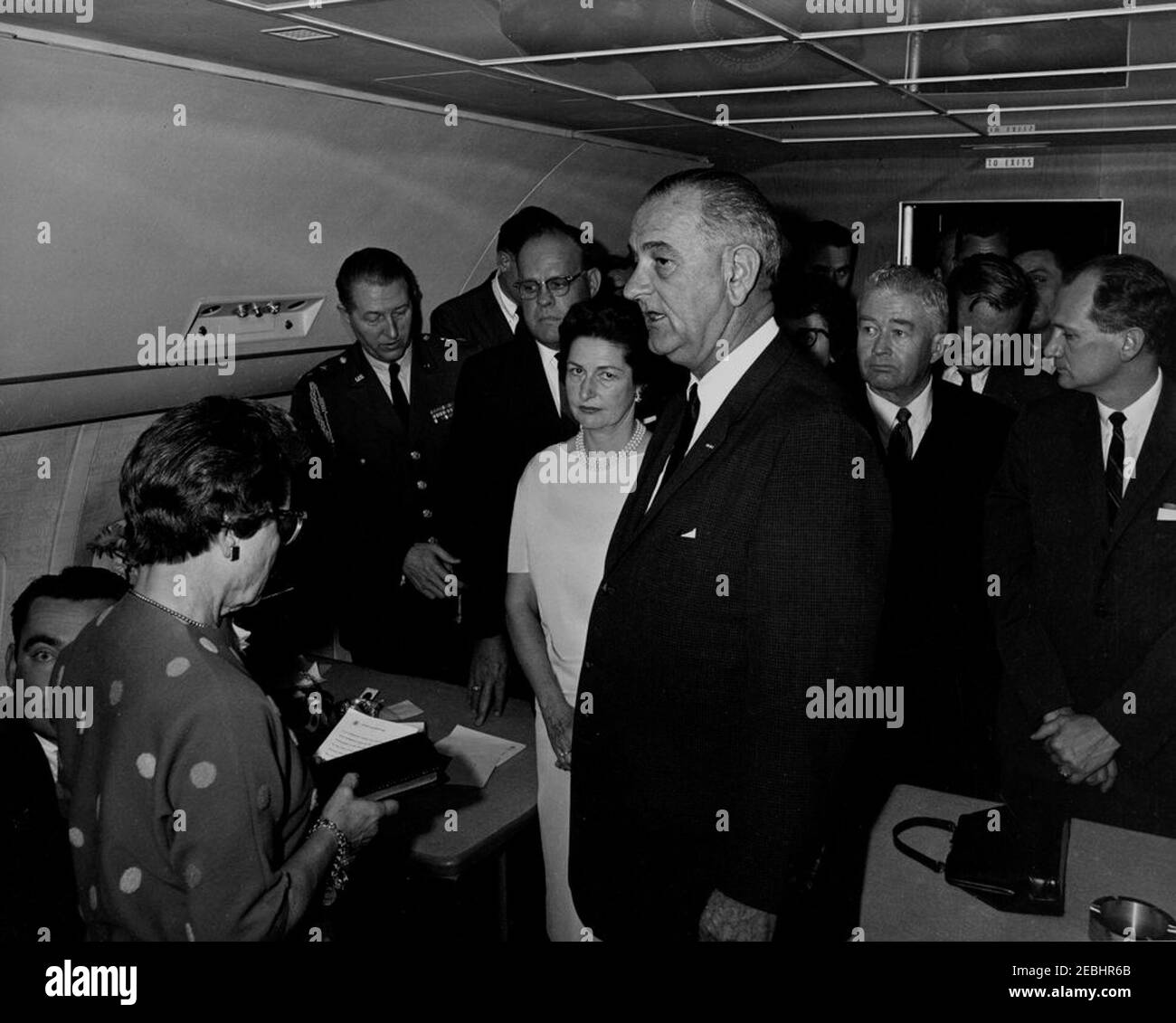

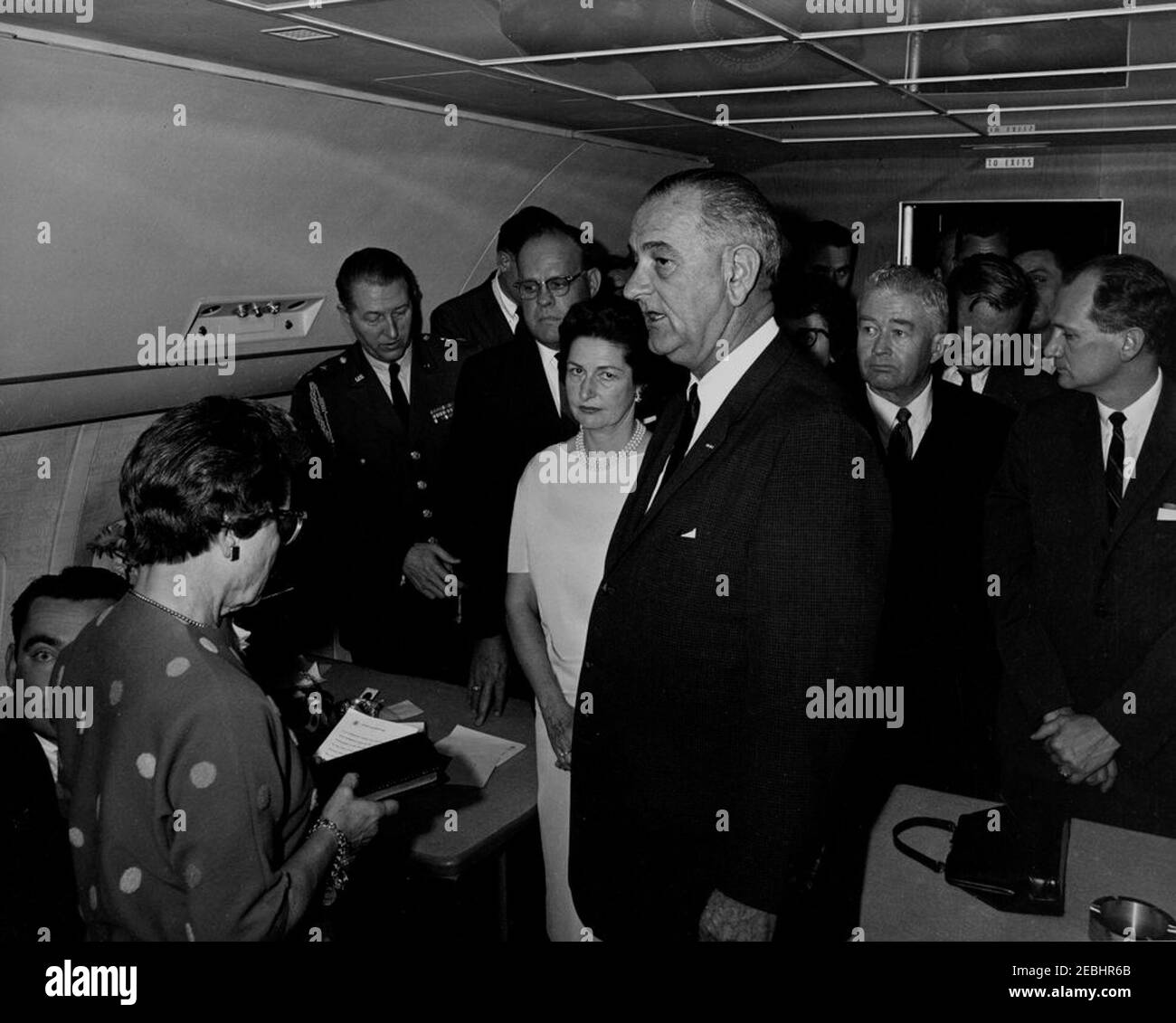

Lyndon B.

Johnson, then vice president and later president, has been the subject of numerous books and articles alleging involvement in corruption, political hardball tactics, and, in more extreme versions, criminal conspiracies.

Mainstream historians acknowledge Johnson as a deeply complex and ruthless political operator, but they overwhelmingly reject claims that he orchestrated violent crimes, citing a lack of credible documentary proof.

Within that environment, Wallace has often been cast by some authors as a shadowy figure operating at the margins of political intrigue.

Stories about suspicious deaths, suppressed investigations, and threatened witnesses appear frequently in these accounts.

However, many of these claims rely on secondhand testimony, disputed timelines, or sources that cannot be independently verified.

The result is a narrative that is compelling but remains outside the consensus of academic and legal history.

The fingerprint affidavit did not lead to a reopened criminal case or official revision of the assassination record.

Instead, it became part of a growing body of alternative research that circulates in documentaries, books, and online forums.

A television documentary in the early 2000s featured the Wallace fingerprint claim, bringing it to a broader audience, but the episode itself became controversial and was later withdrawn from regular broadcast amid legal and reputational concerns.

For some observers, the very resistance to the theory reinforces their suspicion that uncomfortable truths are being avoided.

For others, the episode illustrates the difficulty of separating genuine anomalies from conclusions that stretch beyond the available evidence.

The Kennedy assassination has generated thousands of leads, documents, and claims over six decades; not all can be reconciled into a single coherent explanation.

What makes the fingerprint story endure is its tangible nature.

Unlike anonymous tips or fading memories, a fingerprint is a physical trace—something that suggests presence, not just rumor.

But even physical evidence must be interpreted, verified, and weighed against competing analyses.

Without broad forensic agreement and clear documentation of chain of custody and comparison methods, such evidence remains contested.

In the end, the Wallace fingerprint stands as one more unresolved thread in a case defined by unresolved threads.

It neither conclusively proves a larger conspiracy nor disappears under scrutiny.

Instead, it occupies a gray zone where suspicion, possibility, and uncertainty intersect.

That gray zone is where much of the Kennedy assassination debate still lives.

Official reports established one version of events; independent researchers continue to probe gaps and inconsistencies.

Between them lies a landscape of partial answers, disputed findings, and enduring questions.

Whether the unidentified print represents a missed breakthrough or a misinterpreted fragment may never be definitively known.

But its existence—and the arguments surrounding it—remind us that history is not only built from what is proven, but also from what remains uncertain.

In that uncertainty, the past continues to provoke, challenge, and resist closure.

News

Why Did JFK’s Driver Slow Down After Shots Were Fired?

At 12:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade entered Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, and within…

Did LBJ Kill JFK? Part One – The Lead up

For more than half a century, one of the most debated chapters in American political history has remained a battleground…

JFK’s Granddaughter Tatiana Schlossberg Funeral, Mother Caroline Kennedy Tribute Is STUNNING!

The final days of December carried a weight no family, no matter how strong or resilient, can ever truly prepare…

Every Woman Robert Kennedy Had an Affair With

In photographs from the 1950s and 60s, Ethel Kennedy looks like the picture of American political grace. She stands beside…

Harry EMBARRASSES Himself in Court as His Legal Team WALKS OUT Mid-Trial

It was meant to be a defining chapter in Prince Harry’s long and very public battle with the British tabloid…

Prince William DRAGS Camilla Out — After Guard Catches Her SLAPPING Charlotte on CCTV

Staff Sergeant David Mitchell had built a career on noticing what others dismissed. After more than two decades in military…

End of content

No more pages to load