The morning of November 22, 1963, began like a celebration.

Crowds filled the streets of Dallas, Texas, eager to catch a glimpse of President John F. Kennedy and the First Lady as their motorcade passed through the city.

Smiles, waving hands, and the optimism of a nation still defined the atmosphere—until the procession turned from North Houston Street onto Elm Street.

In a matter of seconds, the mood shattered.

Shots rang out from the direction of the Texas School Book Depository.

Panic erupted.

The motorcade surged forward, and by early afternoon, the United States was informed that its president was dead.

Within hours, suspicion focused on a 24-year-old employee of the Depository: Lee Harvey Oswald.

His name would become inseparable from one of the most traumatic moments in American history.

Yet Oswald did not emerge from nowhere.

His path to Dealey Plaza was long, chaotic, and marked by instability, neglect, and a profound sense of alienation.

Born in New Orleans in October 1939, Oswald never knew his father, who died before Lee was born.

His mother, Marguerite, struggled financially and emotionally, drifting from one crisis to another.

Lee’s childhood was defined by constant moves, institutional placements, and emotional deprivation.

His older brothers were sent away to boarding schools and orphanages, while Lee oscillated between babysitters, relatives, and periods of near-total isolation.

Accounts of his behavior were contradictory: some remembered him as sweet and gentle, others as violent, angry, and uncontrollable.

What remained consistent was instability.

Marguerite’s parenting was erratic.

She defended Lee reflexively, dismissed warnings, and appeared incapable of recognizing the severity of his behavioral problems.

Teachers and neighbors observed troubling patterns—violent outbursts, emotional withdrawal, and an inability to form lasting relationships.

By adolescence, Lee had no close friends, no stable home, and no sense of belonging.

He drifted inward, consuming books and ideas that gave structure to his anger.

Oswald’s intellectual curiosity was real.

Despite academic struggles and frequent truancy, he possessed a sharp mind and a strong vocabulary.

In his teenage years, he discovered Marxist literature and embraced it fervently.

Communism offered him a framework that explained his misery and transformed his resentment into ideology.

He began to see himself as morally superior to those around him, misunderstood but destined for significance.

At sixteen, Oswald dropped out of school without informing his family and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps shortly thereafter.

For a brief moment, his life appeared to stabilize.

He excelled in technical training and qualified as a sharpshooter.

But the structure failed to contain him.

His arrogance, disciplinary issues, and ideological clashes led to court-martials and growing disillusionment.

While stationed in Japan, he began studying Russian and openly expressing Marxist sympathies, earning ridicule from fellow Marines.

In 1959, Oswald defected to the Soviet Union.

The decision was impulsive, theatrical, and deeply revealing.

He imagined himself as a historical figure, a man whose choices mattered.

Reality proved harsher.

The Soviets were suspicious and reluctant, and Oswald’s expectations quickly collapsed.

He attempted suicide when his request for citizenship was denied.

Eventually allowed to stay in Minsk, he received material comfort but not fulfillment.

The rigid conformity of Soviet life frustrated him as much as American capitalism once had.

Oswald’s marriage to Marina Prusakova offered temporary purpose, but it too deteriorated.

He became increasingly volatile and abusive.

His grand ideological dreams went unrealized.

By the time he returned to the United States in 1962, Oswald was angry, humiliated, and obsessed with being recognized.

He expected interviews, admiration, and relevance.

Instead, he found obscurity.

Over the following year, his life unraveled.

He bounced between jobs, abused Marina, and became fixated on political violence.

He attempted to assassinate right-wing General Edwin Walker in April 1963, missing only by chance.

He traveled to Mexico seeking asylum again and was rejected.

Each failure compounded his desperation.

By the fall of 1963, Oswald was isolated and unmoored.

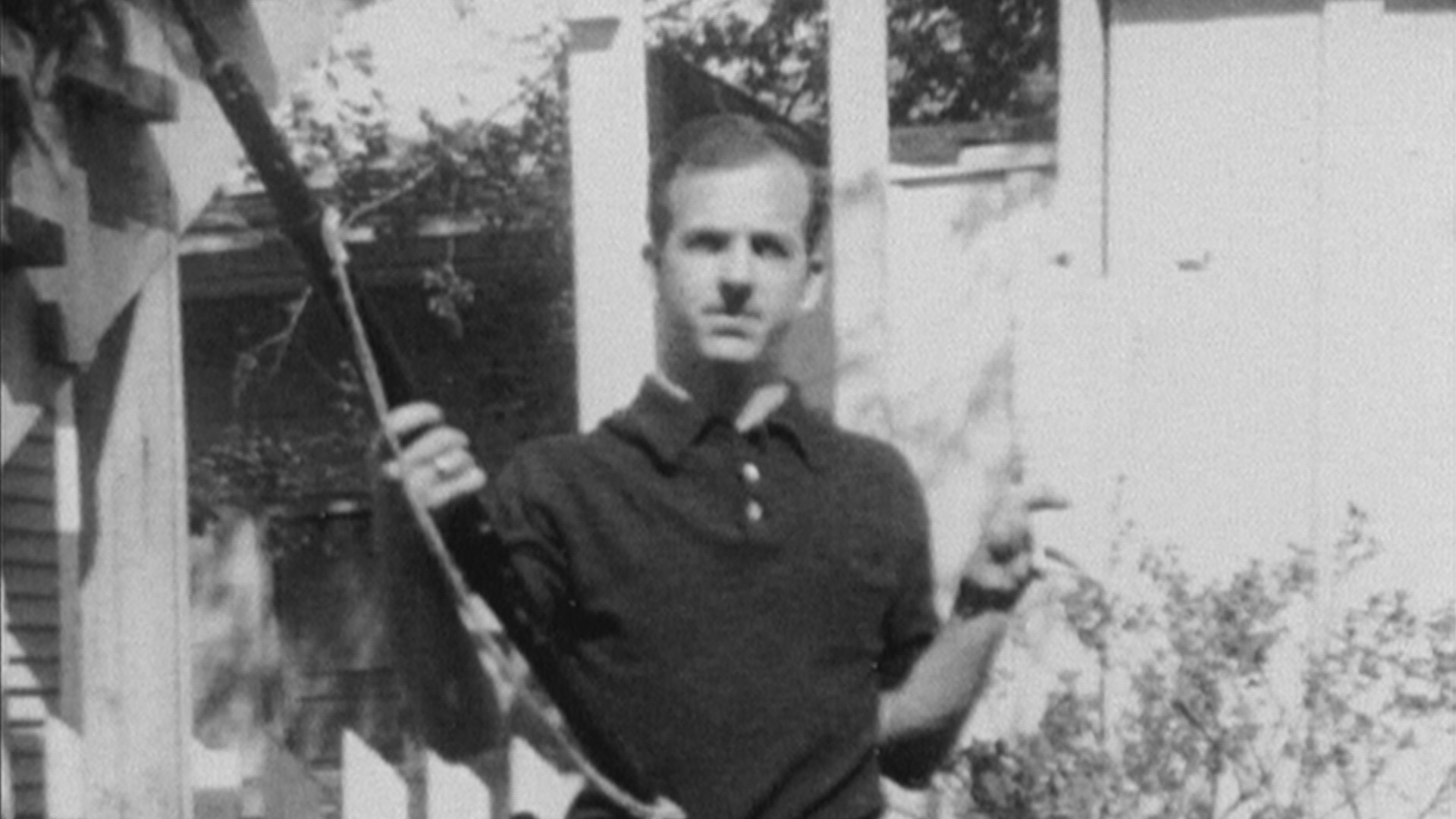

He purchased firearms under a false identity.

He posed for photographs that looked less like documentation and more like prophecy.

When he learned that President Kennedy’s motorcade would pass directly beneath his workplace, the convergence of opportunity and obsession may have felt inevitable.

On November 22, Oswald brought a rifle to work.

Witnesses later placed him on the sixth floor.

Three shots were fired.

President Kennedy was fatally wounded.

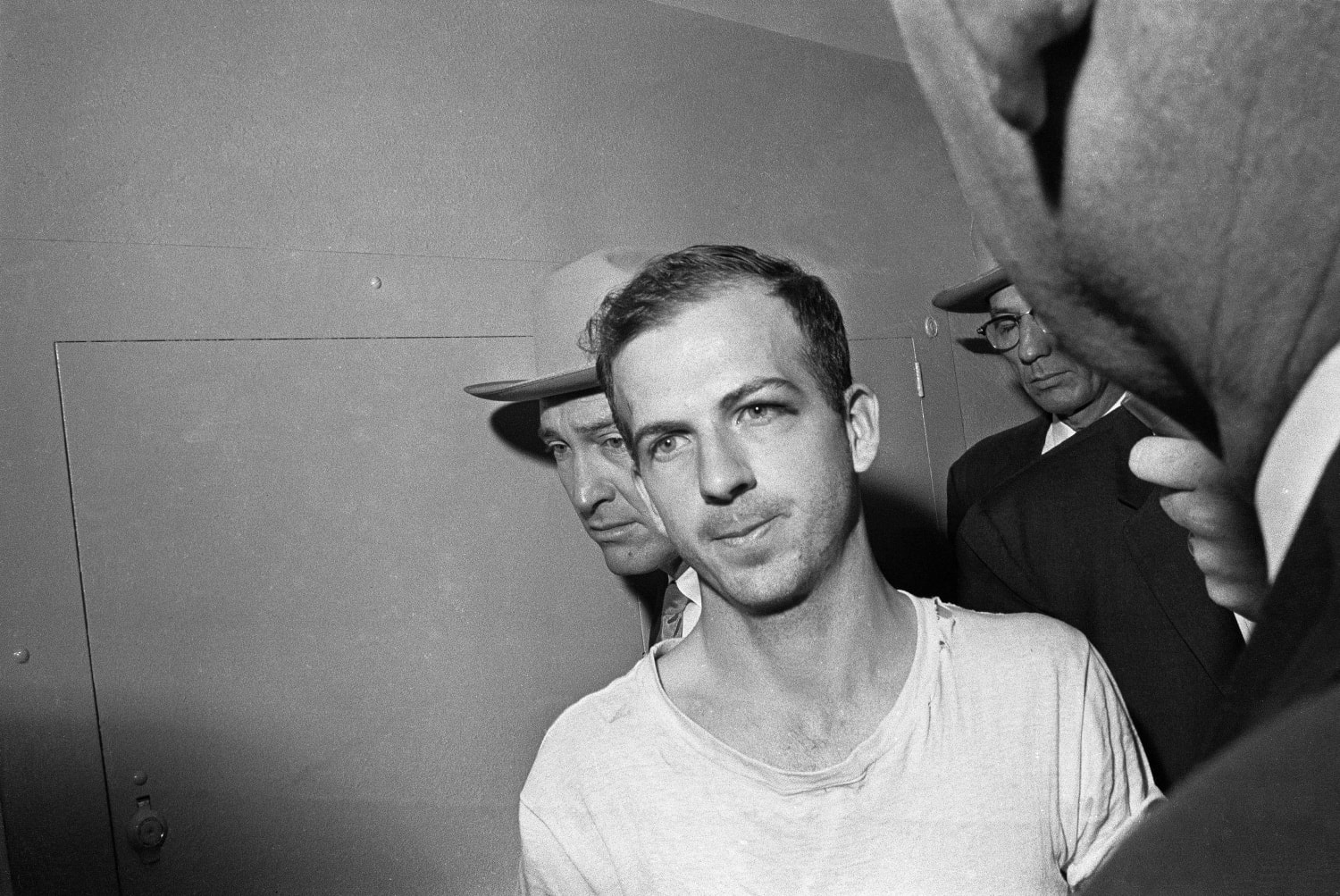

Oswald fled, killed Officer J.D. Tippit during his escape, and was arrested in a movie theater after resisting police.

He denied killing Kennedy but admitted to killing Tippit.

Two days later, before he could stand trial, Oswald was shot dead by Jack Ruby in a police basement.

The man accused of assassinating the president never testified in court.

His death sealed the mystery permanently.

Oswald was buried with almost no mourners.

His name became shorthand for evil, madness, and betrayal.

His mother exploited his infamy for attention and money.

The public searched for larger explanations, conspiracies grand enough to match the magnitude of the crime.

It was easier to believe in shadowy forces than to accept that one deeply disturbed man could alter history so violently.

Yet modern scholarship increasingly suggests exactly that.

A lonely, abused, ideologically obsessed man, driven by resentment and a hunger to be remembered, acted alone.

Not because the story is comforting—but because it is tragic, banal, and frighteningly human.

Whether Oswald killed Kennedy to express rage, fulfill a fantasy of historical importance, or escape his own sense of failure remains unknowable.

What is clear is that his life was a slow march toward destruction, long before Dallas.

His act was not inevitable, but it was comprehensible.

The question that remains is not only who killed Kennedy, but how society allowed someone like Oswald to fall so completely through every possible net.

Sometimes history is not shaped by masterminds in dark rooms, but by broken individuals who desperately want to matter—even if the world burns to remember them.

News

JFK Assassination: Hour By Hour As It Unfolded

On November 22, 1963, the United States did not simply lose a president — it lost its sense of certainty….

Pope Leo XIV Reveals the Forgotten Teaching About Mary’s Heart

Before a single word is spoken, the face reveals what the heart has stored. It is an unspoken language written…

Behind locked doors, cardinals confront Pope Leo XIV — one sentence silences the entire room

The heavy door of the Sala Regia closed with a thud that seemed to seal not just the room but…

Pope Leo XIV Authorizes Scientists to Study a Relic Believed to Be Older Than the Ark Itself

The wooden fragment sat sealed in crystal for three centuries, protected by marble walls and ritual silence. Now, the Vatican’s…

Pope Leo XIV Confirms Discovery of Lost Scrolls That Challenge the Official Biblical Timeline

The folder sat untouched on Cardinal Mendoza’s desk for three days. When he finally broke the seal, his hands trembled….

Pope Leo XIV declares a doctrine obsolete — half the College of Cardinals openly resists

The room fell into a suffocating silence after the decree was read. Then, in a wave of defiance, 53 cardinals…

End of content

No more pages to load