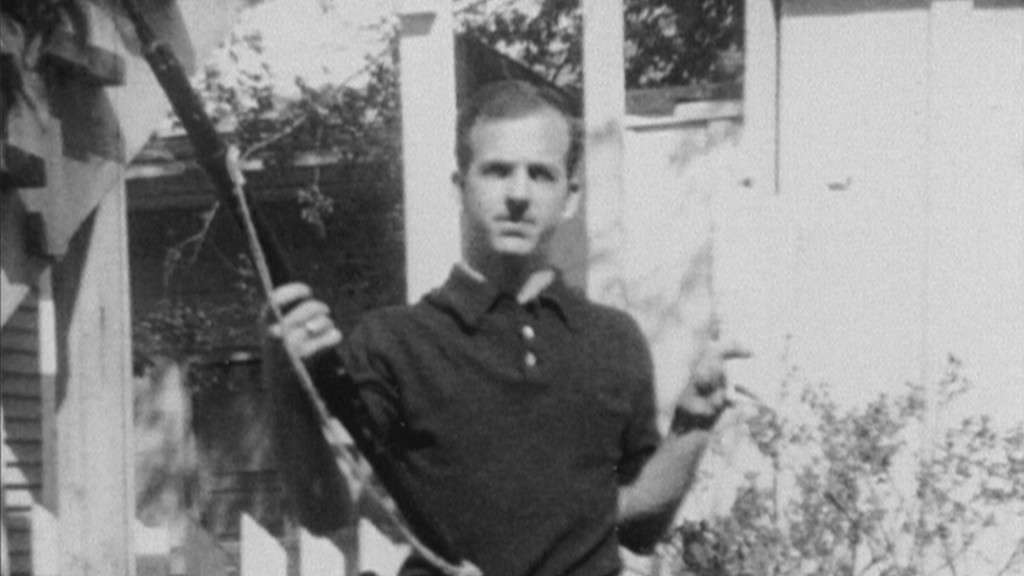

On October 31, 1959, a 19-year-old former U.S.

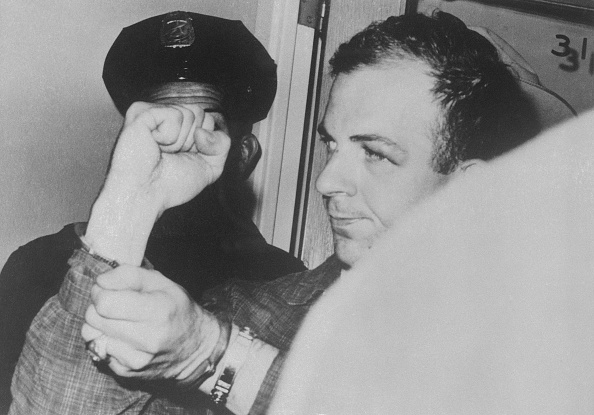

Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald walked into the American Embassy in Moscow and calmly announced he was renouncing his citizenship.

He had arrived in the Soviet Union only weeks earlier, speaking limited Russian and carrying modest savings.

What should have triggered alarm bells instead unfolded with surprising smoothness.

Embassy officials processed his paperwork with bureaucratic efficiency, and Oswald openly stated he intended to share military knowledge with Soviet authorities.

He had served as a radar operator at a base connected to U-2 reconnaissance flights, one of America’s most sensitive Cold War programs.

Under normal circumstances, such a declaration would have prompted intense scrutiny.

A young man offering classified information to the Soviet Union during the Cold War should have become an immediate counterintelligence priority.

Yet the record shows no dramatic intervention, no urgent detention, and no aggressive effort to prevent his defection.

Instead, Oswald soon found himself navigating Soviet bureaucracy with unexpected success.

Before reaching Moscow, Oswald traveled through Europe and arrived in Helsinki, Finland.

There, he applied for a Soviet visa and received approval in just a few days.

At the time, American citizens often faced long waits and extensive vetting.

His rapid clearance raised eyebrows among later researchers who questioned how a teenager with limited language skills and no obvious connections moved so quickly through such a tightly controlled system.

When Soviet authorities initially denied his request to stay, Oswald staged a dramatic gesture, reportedly injuring himself in a Moscow hotel room.

Shortly afterward, officials reversed course and granted him residency in Minsk.

The city was not a remote labor outpost but an industrial center.

Oswald was assigned work in an electronics factory, provided an apartment, and received financial support that allowed him to live more comfortably than many Soviet citizens.

This period in Minsk remains one of the most debated chapters of his life.

Oswald socialized, dated, attended cultural events, and eventually married Marina Prusakova, a young woman whose relatives reportedly had ties to Soviet institutions.

Whether their relationship was purely personal or had additional dimensions has never been conclusively established.

What is clear is that Oswald’s life in the Soviet Union was neither impoverished nor isolated.

He was monitored by Soviet authorities, but he was also permitted a level of stability that seemed unusual for a recent defector.

After roughly two and a half years, Oswald requested permission to return to the United States.

Given his earlier threats to disclose military information, one might expect a difficult path home.

Instead, his repatriation unfolded with surprising ease.

American officials approved travel documents, extended a loan to cover expenses, and allowed his Soviet-born wife to accompany him.

Upon arrival in the U.S., Oswald did not face public prosecution for defection.

Nor was there visible evidence of prolonged detention or highly publicized legal action.

This smooth reentry has fueled decades of speculation.

Some researchers argue it suggests official interest in Oswald, perhaps even protection.

Others counter that bureaucratic confusion and Cold War complexities often produced inconsistent outcomes.

Defectors were sometimes treated harshly, sometimes quietly debriefed and released, depending on circumstances that were not always visible to the public.

Questions about Oswald’s time abroad intensified after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963.

Investigators discovered that Oswald had traveled to Mexico City just weeks earlier, visiting the Soviet and Cuban embassies.

U.S. intelligence intercepted communications related to those visits, but the full picture of what occurred remains debated.

The timing alone deepened suspicions for those who believed Oswald’s history suggested connections beyond a solitary political grievance.

Complicating matters further was the later defection of a KGB officer who claimed the Soviets had reviewed Oswald and considered him unstable and unsuitable as an agent.

Some American intelligence officials accepted that account; others distrusted it, suspecting deliberate misinformation.

The disagreement underscored how little certainty existed even within agencies tasked with evaluating such claims.

Historians continue to argue over whether Oswald was ever formally recruited by any intelligence service.

Some see him as a volatile individual whose ideological leanings and erratic behavior made him difficult to control.

Others believe he may have been observed, tested, or informally used without becoming a disciplined operative.

The absence of definitive documentation leaves space for both skepticism and suspicion.

What remains undeniable is the unusual sequence of events: a teenager defects at the height of superpower tension, lives under close watch yet relative comfort in the Soviet Union, returns to the United States with little visible consequence, and later stands accused of assassinating a president.

Each stage can be explained individually through ordinary bureaucratic or political factors.

Taken together, they form a pattern that many find difficult to dismiss as coincidence.

More than six decades later, government files related to Oswald and intelligence operations of the era remain partially classified.

Officials cite national security, diplomatic sensitivities, and the protection of sources and methods.

Critics argue that the continued secrecy sustains doubt and erodes public trust.

If Oswald truly acted alone, they ask, what danger could full disclosure still pose?

Lee Harvey Oswald’s life intersects with some of the most guarded institutions of the Cold War: military intelligence, Soviet security services, and American diplomatic channels.

Whether he was a pawn, an opportunist, or something in between, his story reveals how individual lives can become entangled in systems designed to operate in secrecy.

The unanswered questions surrounding his journey from Marine radar operator to Soviet resident and back again remain central to the enduring mystery of the Kennedy assassination.

News

What Richard Nixon Finally Admitted About John F. Kennedy After He Died

November 25, 1963. The Capitol Rotunda stood hushed beneath its towering dome as Americans filed past the flag-draped coffin of…

The Death Of JFK Jr: Is The Kennedy Curse Real?

John F. Kennedy Jr. entered the world as American royalty. Born just weeks after his father won the presidency, he…

🎧 Who REALLY Killed JFK? The Case Files They Hid For 60 Years

In the autumn of 1960, while cameras captured the polished image of a rising political star, a very different scene…

Did LBJ Kill JFK? Part Two – The Cover-up

In the chaotic hours following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the official story began forming almost as quickly…

✝️ Pope Leo XIV Shakes The World: He Eliminates Eleven Sacred Ceremonies!

A dramatic narrative has been circulating online, claiming that a newly reigning pope has issued an unprecedented decree abolishing numerous…

CHECK YOUR CUPBOARD! — 6 ITEMS THAT STOP THE ENEMY IN DARKNESS | Pope Leo XIV Teachings Today

Across social media platforms and online religious communities, a dramatic message has been gaining traction, delivered in the tone of…

End of content

No more pages to load