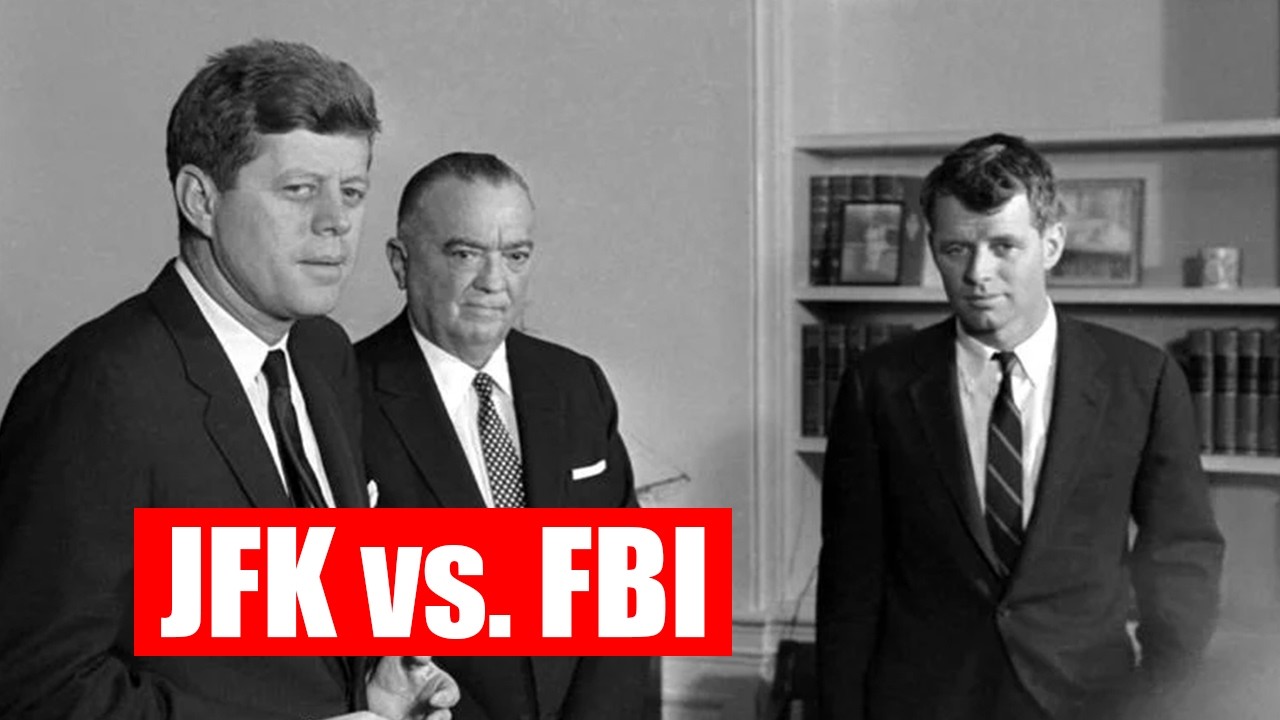

At 10:30 a.m. on March 22, 1962, the atmosphere inside the Oval Office was unusually tense. President John F. Kennedy sat behind his desk, confident in his authority yet unaware that the thin manila folder placed before him carried more weight than most laws he would sign that year. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, did not raise his voice or make demands. He simply opened the file and allowed the contents to speak. Inside were detailed records of Kennedy’s affair with Judith Campbell Exner — a woman who was simultaneously involved with Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, one of the very criminals the FBI was supposed to be targeting. In that moment, Hoover did not need to threaten the president. The message was implicit and unmistakable: I know everything. And if I know, you are vulnerable.

Kennedy ended the affair that same day. Phone calls stopped. White House visits ceased. A relationship that had lasted over a year vanished instantly. Not because of morality or political principle, but because Hoover had demonstrated his leverage. It was not the first time he had used information to exert influence, and it would not be the last.

Hoover’s power did not come from ballots or congressional approval. It came from files — thousands of them, stored across four rooms at FBI headquarters. For 48 years, from 1924 until his death in 1972, Hoover ran the Bureau of Investigation, later renamed the FBI, as his personal fiefdom. He built it into a formidable law enforcement agency, creating a national fingerprint database, modern forensic labs, and professional training programs that reshaped American policing. Yet alongside these achievements, he constructed a surveillance empire that made even presidents uneasy.

Hoover collected secrets on nearly everyone who mattered: presidents, senators, congressmen, civil rights leaders, journalists, celebrities, and business elites. His dossiers included extramarital affairs, financial improprieties, alleged communist sympathies, gambling debts, and anything else that could be politically weaponized. He rarely threatened openly. He preferred a subtler approach — letting powerful figures know he possessed compromising information, and allowing fear to do the rest.

In Washington, it was widely believed that Hoover wielded more influence than the president. Leaders came and went every four or eight years; Hoover remained. He outlasted Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Each of them understood that crossing him could carry devastating consequences.

Publicly, Hoover presented himself as America’s moral guardian — a tireless defender against crime and communism. Privately, his behavior contradicted that image. He maintained a vast collection of pornographic material, including nude photographs of celebrities, which he reportedly used both for personal gratification and potential blackmail. His close personal relationship with FBI Associate Director Clyde Tolson, with whom he lived and traveled extensively, further exposed the hypocrisy of a man who policed others’ morals while shielding his own.

By the time Kennedy entered the White House in 1961, Hoover was 66 years old and nearing the mandatory retirement age of 70. He knew the young president wanted him gone. Kennedy, only 43, represented everything Hoover despised: youthful energy, progressive ideals, and a willingness to challenge entrenched power.

The clash between them was inevitable from day one. Kennedy appointed his brother, Robert “Bobby” Kennedy, as Attorney General — technically Hoover’s superior. For decades, Hoover had bypassed the Attorney General to report directly to presidents. Bobby Kennedy ended that privilege, forcing all FBI communications through his office. The move humiliated Hoover and ignited a quiet war.

Bobby frequently confronted Hoover, sometimes deliberately interrupting his afternoon naps or dragging him to casual lunches at drugstores — a clear signal that Hoover was no longer untouchable. In response, Hoover escalated his collection of damaging material on the Kennedys, particularly regarding JFK’s affairs and alleged connections to organized crime.

The Judith Exner affair was particularly dangerous. Introduced to Kennedy by Frank Sinatra during the 1960 campaign, Exner moved in elite social circles while also maintaining a relationship with Giancana. The FBI had been monitoring Giancana for years, and Hoover’s agents tracked Exner’s calls, movements, and meetings. When Hoover presented this information to Kennedy, it was a calculated display of power — proof that the Bureau could expose the president at any moment.

This was not the only time Hoover used such leverage. In 1963, he privately told Bobby Kennedy that he had evidence JFK had paid a woman $500,000 to prevent a lawsuit over a decade-old affair. Hoover did not present this as part of an investigation. It was a reminder: I know your family’s secrets.

While JFK and Hoover engaged in passive-aggressive skirmishes, Bobby Kennedy waged open war against the FBI director. As Attorney General, Bobby prioritized civil rights and organized crime investigations — areas Hoover had long neglected or resisted. He coordinated federal agencies to pursue mob leaders like Giancana, Carlos Marcello, and Santo Trafficante, infuriating Hoover.

Yet Bobby also made a fateful decision. Seeking to disprove Hoover’s claims that civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was influenced by communists, he authorized FBI wiretaps on King. Instead of clearing King’s name, Hoover weaponized the surveillance, collecting evidence of King’s extramarital affairs and even sending him an anonymous blackmail letter urging him to consider suicide. Years later, Bobby deeply regretted approving those wiretaps.

As tensions mounted, Bobby explored ways to force Hoover into retirement when he turned 70 in January 1965. But Hoover had already secured his position. His files were his insurance policy. Presidents Truman and Kennedy had considered firing him, but both concluded the political fallout would be catastrophic. Nixon later admitted on tape that fear of Hoover’s retaliation kept him from removing the FBI director.

The Kennedys faced an additional complication: Hoover had extensive files on their father, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., including alleged ties to gangsters and controversial business dealings. After Joe Kennedy suffered a debilitating stroke in December 1961, his sons lost a key ally who had previously managed Hoover with careful diplomacy.

Then came November 22, 1963. In Dallas, President Kennedy was assassinated. Within hours, Hoover seized control of the investigation, sidelining local police and the Secret Service. He quickly pushed the conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, rejecting any possibility of conspiracy.

Declassified memos later revealed Hoover’s focus was not on uncovering the full truth but on shaping public perception. One memo noted his desire to “convince” the public that Oswald was the sole assassin — language that raised troubling questions about objectivity.

A 1976 House committee later criticized the FBI’s investigation for failing to seriously explore conspiracy theories. But in the immediate aftermath, Hoover’s primary concern was securing his own future.

With Lyndon B. Johnson now president, Hoover found a more compliant ally. Johnson reportedly feared Hoover’s files on his own scandals, just as Kennedy had. In 1964, Johnson granted Hoover an unprecedented exemption from mandatory retirement, allowing him to remain FBI director indefinitely. Hoover would serve until his death in 1972, overseeing nine more years under Johnson and Nixon.

Bobby Kennedy, no longer Attorney General after resigning to run for Senate, continued to clash with Hoover until his own assassination in 1968. Even then, Hoover could not resist leaking information to undermine Bobby’s legacy.

In the years following Hoover’s death, revelations about his abuses gradually surfaced — illegal surveillance, political blackmail, and manipulation of investigations. Public trust in the FBI declined sharply, from 84 percent in 1965 to just 37 percent today.

Congress responded by imposing a 10-year term limit on FBI directors, specifically to prevent another Hoover from accumulating unchecked power. Yet the imposing J. Edgar Hoover Building still stands in Washington, a controversial monument to a man whose legacy remains deeply divided.

The March 22, 1962 meeting between Hoover and Kennedy encapsulates a broader truth about American democracy. The president possessed formal authority, but Hoover possessed something more dangerous: information. Kennedy could have fired him, but fear of exposure kept him in check. Power, in that moment, belonged not to the elected leader but to the man with the files.

Hoover’s story is not simply about one director or one president. It is a cautionary tale about institutional power, secrecy, and the erosion of accountability. Democracies do not always fall through dramatic coups; sometimes they are undermined quietly, through dossiers, surveillance, and the subtle manipulation of fear.

For nearly half a century, Hoover turned information into control. He outlasted presidents, shaped investigations, and dictated narratives. His reign ended in 1972, but the questions he left behind remain hauntingly relevant: Who truly holds power? How much secrecy is too much? And what happens when those meant to serve the public instead hold it hostage through hidden knowledge?

News

Trump Walks Out Mid-Meeting — White House Scrambles

It was supposed to be just another tense White House meeting, the kind that happens every day when power, politics,…

TRUMP’S LAST STAND: Power, Ego, and the Law Finally Clash

The moment when a leader truly crosses a line is rarely announced with a siren or a headline. It begins…

Trump PANICS After Judge Issues SHOCK Warning — Jail Is Next

The change in the air was subtle at first, the kind of shift you feel before you fully understand it….

Donald Trump SCARED of Arrest — Federal Court Orders Instant Action

Dawn in Washington usually brings routine. Morning news cycles, legal filings filed quietly, political posturing that unfolds at a measured…

Trump CAUGHT OFF GUARD as Senate WALKOUT Shocks Washington

The Senate chamber is designed to project permanence. Heavy wood, tall ceilings, solemn rituals, and a rhythm of procedure that…

The Life & Assassination Of Robert Kennedy: What If He Lived?

January 20, 1969 should have been Robert Francis Kennedy’s inauguration day. The crowds, the oath, the promise of a new…

End of content

No more pages to load