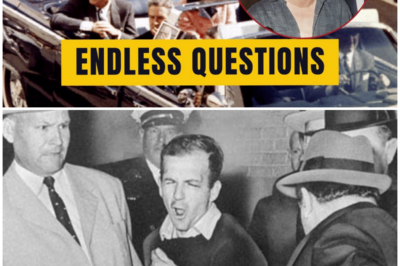

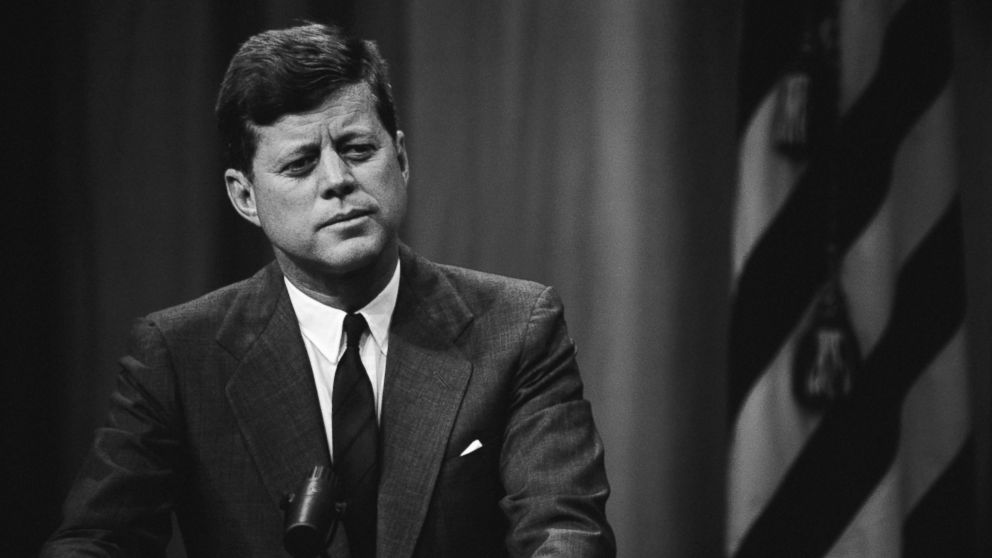

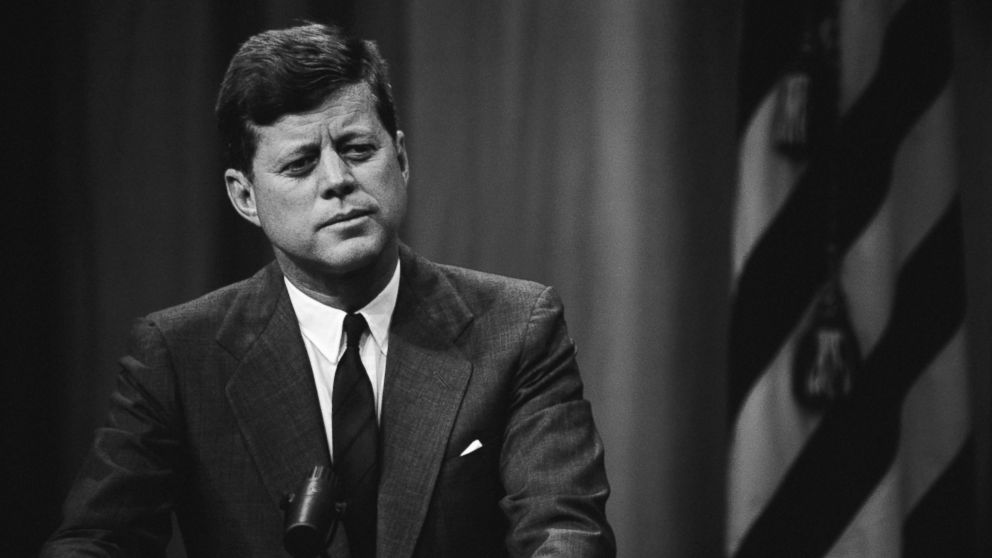

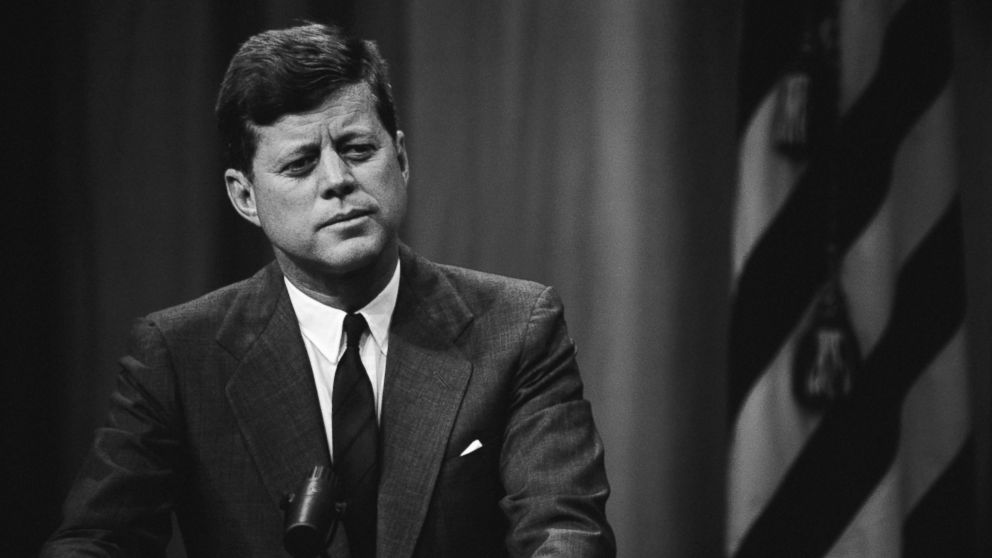

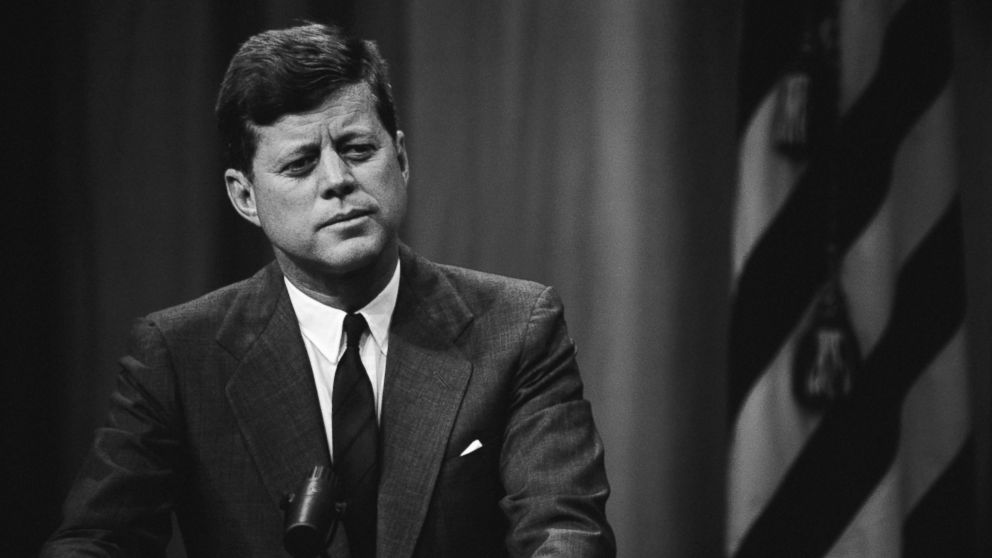

On June 5, 1963, inside a quiet suite at the Cortez Hotel in El Paso, President John F.

Kennedy asked a question that would later sound like a premonition.

He had resisted traveling to Texas for months, uneasy about the political hostility and volatile atmosphere, yet the pressure had become impossible to ignore.

Vice President Lyndon B.

Johnson and Texas Governor John Connally sat across from him as Kennedy finally asked whether the trip to Texas would ever be resolved.

Connally later recalled that moment with chilling clarity, sensing that the decision was no longer Kennedy’s to make.

Five months later, Kennedy was dead, shot in Dallas—Johnson’s home state, Johnson’s territory.

Officially, Kennedy traveled to Texas to mend fractures within the Democratic Party and prepare for his 1964 reelection campaign.

Texas was a crucial swing state, and Kennedy had narrowly won it in 1960.

On paper, the trip made political sense.

In reality, Kennedy had viewed Texas as dangerous, unpredictable, and increasingly hostile.

Only weeks before his visit, U.S.

Ambassador Adlai Stevenson had been spat on and assaulted by right-wing protesters in Dallas.

Advisors warned Kennedy that the climate was unsafe.

Still, the trip went forward, not because Kennedy wanted it, but because Johnson insisted.

By 1963, Kennedy and Johnson’s relationship had deteriorated badly.

Once politically inseparable, they had become distant to the point of near exclusion.

Johnson was frozen out of major decisions and reduced to a ceremonial role he openly despised.

Kennedy’s private secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, documented the growing rift.

In 1961, Kennedy met privately with Johnson for more than ten hours.

In 1963, their total private meeting time amounted to barely over an hour.

More damning still, Kennedy had decided to remove Johnson from the 1964 ticket, a decision he reportedly confirmed just days before traveling to Dallas.

Despite this, Johnson argued relentlessly that the Texas trip was essential.

Without Texas, he warned, reelection would be difficult.

He promised party unity, enthusiastic crowds, and smooth logistics.

Kennedy agreed reluctantly, unaware of how much control he was surrendering.

Planning for the visit was largely handed over to Texas officials under Governor Connally’s supervision, with local authorities given extraordinary influence over routes, schedules, and security.

The Secret Service coordinated, but relied heavily on local cooperation.

In Texas, that meant relying on people loyal to Lyndon Johnson.

Dallas in 1963 was governed by Mayor Earl Cabell, a conservative anti-communist whose hostility toward Kennedy’s policies was no secret.

Years later, declassified records revealed that Cabell had been a CIA asset since the mid-1950s.

Even more unsettling was the identity of his brother: General Charles P.

Cabell, the former Deputy Director of the CIA.

After the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy forced both CIA Director Allen Dulles and Charles Cabell out of office.

The general left embittered and openly critical of Kennedy, whom he reportedly described as a traitor.

This placed Kennedy in a city where the mayor overseeing his visit had intelligence ties and a deeply personal grievance against him.

As mayor, Cabell approved the motorcade route, supervised ceremonial arrangements, and oversaw the Dallas Police Department responsible for protecting the president.

These facts are documented, not speculative, and they frame the environment in which Kennedy entered Dallas.

The motorcade route itself raised serious concerns.

Rather than taking a direct, secure path from Love Field Airport to the Trade Mart, where Kennedy was scheduled to speak, the motorcade followed a winding route through downtown Dallas.

It included a sharp turn onto Elm Street that slowed the presidential limousine to roughly 11 miles per hour as it passed the Texas School Book Depository.

Tall buildings lined the route, windows remained unsecured, and no officers were stationed inside the depository.

Standard security protocols were ignored in favor of maximum public exposure.

Local officials justified the route as a publicity decision, designed to allow more citizens to see the president.

The route was even published in local newspapers days in advance.

Yet the decision to hold the luncheon at the Trade Mart—rather than a more secure venue—made this dangerous route unavoidable.

That choice, too, was made by local Texas officials.

Security became secondary to optics, and the consequences would prove fatal.

Johnson’s position in the motorcade added another layer of intrigue.

He rode several cars behind Kennedy, close enough to witness events, far enough to be protected.

Witnesses later claimed Johnson ducked down moments before or immediately after the shots rang out.

His Secret Service agent, Rufus Youngblood, testified that he shielded Johnson after the first shot, but some accounts suggest Johnson was already reacting before the chaos fully erupted.

While definitive proof remains elusive, the timing continues to fuel suspicion.

After the shooting, Johnson’s car did not immediately follow Kennedy’s limousine to Parkland Hospital.

There was a brief delay while communications took place.

Once at the hospital, Johnson was quickly surrounded by Secret Service agents and urged to leave Dallas.

Despite fears of a broader conspiracy, no attempt was ever made on Johnson’s life.

Within 98 minutes of Kennedy’s death, Johnson was sworn in as president aboard Air Force One, perfectly positioned to assume power.

In the aftermath, investigations into Johnson’s own political scandals abruptly stopped.

Allegations involving Bobby Baker, Billy Sol Estes, and corporate corruption faded into silence.

Johnson formed the Warren Commission, selected its members, and oversaw an investigation that concluded Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.

Oswald, of course, was murdered before he could testify.

There is no document that proves Johnson ordered Kennedy’s assassination.

No confession, no signed directive.

What exists instead is a pattern of control.

Johnson insisted on the trip.

Johnson’s allies planned it.

Johnson’s loyal local officials handled security.

Johnson survived, ascended to power, and benefited politically from Kennedy’s death.

To accept the official story requires accepting a cascade of coincidences so vast that it strains belief.

Kennedy did not need to be betrayed by a single mastermind pulling every string.

All that was required was a setting where safeguards failed, where local authority trumped federal caution, and where opportunity met motive.

Texas provided that setting.

Dallas delivered the outcome.

When Kennedy asked in El Paso whether the Texas trip would ever be worked out, he likely believed he was making a political concession.

In reality, he may have been stepping into a trap shaped by territory, loyalty, and ambition.

Whether by design or by catastrophic neglect, the result was the same.

In Dallas, on Lyndon Johnson’s home turf, John F.

Kennedy was killed.

The echo of that moment still reverberates, challenging history to explain whether it was coincidence—or the perfect crime.

News

BREAKING: Ex-Husband Arrested in Ohio Dentist, Wife Murders

The murders of Spencer and Monnique Tepee sent a wave of horror through Columbus, Ohio, and far beyond its borders,…

FBI Agent Resigns Over Investigation Into Shooting of Renee Good

The resignation of a senior FBI supervisor from the Minneapolis field office has added a startling new twist to an…

Alex Pretti was killed by ‘Trump’s cowardly ICE thugs’ says parents

Minneapolis has become a city where mourning feels perpetual. Just as residents struggle to heal from past traumas, another death…

The Tragic Rift Between Jackie Kennedy and Her Sister

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis occupies a singular place in American history. She is remembered as the elegant First Lady who…

Why Everyone Thinks the Mafia Killed JFK

On November 22, 1963, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy shattered more than a presidency. It fractured the public’s…

JFK And Carolyn’s Wedding: The Lost Tapes

For much of his life, John F. Kennedy Jr. belonged to the world before he ever belonged to himself. Born…

End of content

No more pages to load