Dorothy Kilgallen and the Questions That Refused to Die

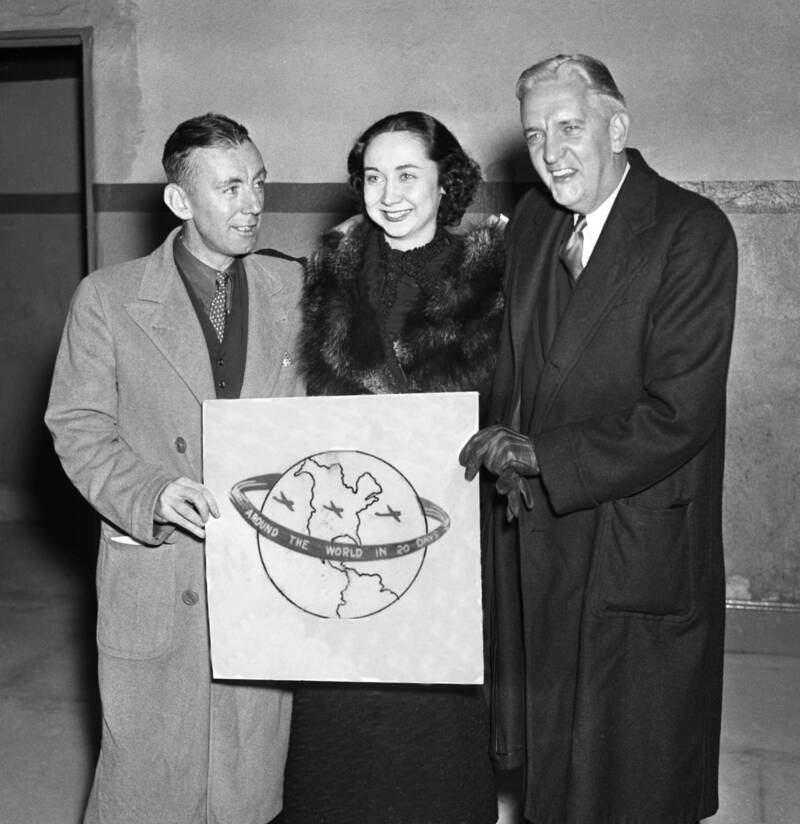

Dorothy Kilgallen was born on July 3, 1913, in Chicago, into a household where newsprint and deadlines were a way of life.

Her parents, James Kilgallen and Mae Ahern, were both newspaper reporters, and their profession ensured that Dorothy grew up constantly on the move, absorbing the rhythm of journalism from an early age.

By 1920, the family settled in Brooklyn, New York, where Dorothy’s sharp intellect and fearless curiosity quickly set her apart.

At just eighteen years old, she became a reporter for the New York Evening Journal, a rare achievement for a woman of her age in an industry still dominated by men.

Her rise was swift.

By 1938, Dorothy was writing a nationally syndicated daily column for the New York Journal-American.

Her work effortlessly bridged hard news and entertainment, moving from courtroom drama to Broadway gossip with equal authority.

She covered some of the most notorious criminal trials of the era, including the case of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, convicted of kidnapping and murdering the infant son of Charles and Anne Lindbergh.

Yet she also reveled in the glamour of theater and Hollywood, cultivating friendships with stars and powerbrokers alike.

In 1940, Dorothy married Dick Kollmar, a charismatic performer from Broadway musicals.

Together, they became a media powerhouse.

They hosted radio programs, including the popular Breakfast with Dorothy and Dick, and later achieved national fame as a married panelist duo on the television game show What’s My Line?.

With three children and a lavish Manhattan townhouse, their public image embodied postwar American success.

Dorothy was everywhere—on television, on the radio, in print—traveling constantly, hosting glittering parties, and shaping public opinion with her words.

Among her acquaintances were Marilyn Monroe and a rising politician from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy.

These friendships would later place Dorothy at the center of two of the twentieth century’s most enduring mysteries.

In August 1962, Dorothy published a gossip column about Monroe, based on a recent face-to-face interview.

She hinted that the actress had met someone new, a man more powerful than any she had known before.

The name was withheld, but the suggestion was explosive.

The very next day, Marilyn Monroe was found dead in her Brentwood home.

Authorities ruled Monroe’s death a suicide caused by a barbiturate overdose.

Dorothy, however, was unconvinced.

She knew Marilyn’s habits intimately and publicly questioned the official narrative.

Why was Monroe found nude, when she never slept that way? Why was the bedroom light on and the door locked? How could she have swallowed dozens of pills without a glass of liquid nearby? Dorothy raised these questions in print, not accusing anyone directly, but forcing the public to confront the inconsistencies.

Despite her efforts, the case was never reopened, and Monroe’s death slipped into legend and speculation.

Dorothy’s private life, meanwhile, was far less pristine than her television persona suggested.

She had a tumultuous marriage, a discreet affair with singer Johnny Ray, and public feuds with powerful media figures such as Jack Paar and Frank Sinatra.

She was admired, envied, and resented in equal measure—a dangerous combination for someone who refused to soften her reporting.

Then came November 22, 1963.

The assassination of President John F.

Kennedy devastated the nation and struck Dorothy personally.

She had known Kennedy socially and admired him deeply.

As a journalist, she immediately began scrutinizing the details emerging from Dallas.

The more she learned, the less convinced she became that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone.

In a widely read article titled “The Oswald File Must Not Close,” Dorothy criticized the Dallas police for their lax security and questioned how Jack Ruby could have murdered Oswald inside police headquarters.

When Ruby stood trial, Dorothy immersed herself in the case.

She interviewed Ruby directly, dined with his attorney Melvin Belli, and gathered notes no other reporter possessed.

She explored the possibility that Ruby and Oswald knew each other and followed leads that suggested a much larger conspiracy.

As the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald was the sole gunman, Dorothy remained skeptical.

She continued asking uncomfortable questions, including why Oswald allegedly shot Officer J.D.Tippit and why witness accounts conflicted so sharply.

By 1965, Dorothy had decided to write a book about the assassination.

She traveled to New Orleans, convinced she was close to a breakthrough that would “blow the case wide open.

” Friends recalled her excitement and her certainty that she had uncovered something extraordinary.

On November 7, 1965, she appeared on television, sharp and confident as ever.

The following morning, she was found dead.

Dorothy Kilgallen’s body was discovered in a guest room she never used.

She was fully dressed in an evening gown, wearing a wig and makeup, propped upright in bed with a book she had already read resting on her lap.

Two types of sleeping pills were found nearby.

The medical examiner ruled her death accidental, citing a combination of barbiturates and alcohol, with circumstances listed as undetermined.

The similarities to Marilyn Monroe’s death were chilling.

Even more troubling was what was missing.

Dorothy’s notes for her JFK book were nowhere to be found.

According to author and friend Mark Lane, she had confided that she possessed evidence proving Oswald did not act alone.

After her death, Lane claimed that Dorothy’s husband admitted destroying the papers, saying that enough people had already died.

Witnesses later came forward with unsettling claims, including sightings of Dorothy meeting an unidentified man on the night before her death.

Speculation swirled around possible connections to organized crime, intelligence agencies, and powerful political figures.

No proof ever surfaced, but the questions refused to disappear.

Dorothy Kilgallen was mourned by the public and revered by her peers.

Ernest Hemingway called her the greatest female writer in the world.

Yet her legacy is inseparable from the mysteries that surrounded her final years.

Whether she died by tragic accident or was silenced because she came too close to the truth remains unresolved.

What is certain is that Dorothy Kilgallen never stopped asking questions—and in the end, those questions may have cost her everything.

News

André Rieu’s Son Says Goodbye After His Father’s Tragic Diagnosis

Andre Rieu, the renowned Dutch violinist and conductor famously known as the “King of Waltz,” has recently been the subject…

André Rieu Says Farewell After Devastating Health Revelation

Andre Rieu, the celebrated Dutch violinist and conductor known worldwide as the “King of Waltz,” has been at the center…

Ina Garten Reveals Emotional Update About Her Childhood Abuse by Her Father

Ina Garten, known to millions as the warm and inviting host of Barefoot Contessa, is revealing a deeply personal and…

Tragic Details America’s Test Kitchen Doesn’t Want You To Know

America’s Test Kitchen has built its reputation on authenticity. Unlike many TV cooking sets, ATK boasts real kitchens with working…

Famous Chefs Who Are Totally Different Off-Screen

When you watch a celebrity chef every week, it almost feels like they’re part of your family. Their smiles, jokes,…

Ina Garten Shares Emotional Update about Split from Husband Jeffrey: ‘It Was Real Painful’

Ina Garten’s gentle adjustment of her husband Jeffrey’s appearance for a photo session is a tender moment that belies the…

End of content

No more pages to load