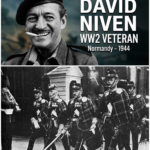

VIn the annals of British cinema, few names conjure the image of Debonire elegance quite like David Nan.

The pencil mustache, the twinkling eyes, the effortless charm that seemed to flow as naturally as the temps through London.

Yet beneath that polished exterior of the quintessential English gentleman lay a story far more remarkable than any script Hollywood could devise.

This is not merely the tale of an Academy Award-winning actor.

This is the story of a man who, when his nation called, abandoned the glittering lights of Hollywood at the height of his fame to dawn the uniform of a British commando.

A man who came under fire in Normandy, narrowly escaped capture in Belgium, and witnessed the chaos of the Battle of the Bulge.

A man whose family history stretched back to one of the most devastating defeats in British military history.

James David Graham Nan entered this world on the 1st of March 1910 at Belgrave mansions Grovener Gardens in the heart of London.

Though he would later claim with characteristic embellishment to have been born in Kirimure in Scotland, his birth was registered in the St.

George Hanover Square district of the capital.

It was the first of many colorful fabrications that would pepper his life story.

Yet the essential truth of the man remained far more compelling than any fiction.

His father, William Edward Graham Nan, was a leftenant in the Berkshire ymanry, a man of modest military distinction who had married into a family with an extraordinary marshall heritage.

His mother, Henrietta Julia Datcha, was born in Brecon, Wales, and carried within her bloodline a connection to one of the most controversial chapters in British imperial history.

Her father, Captain William Degata of the First Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot, had fallen at the battle of Izand Luana during the Anglo Zulu War of 1879.

It was a heritage that would cast a long shadow over the family.

Tragedy struck the Nan household when young David was barely 5 years of age.

In 1915, leftinant William Nan was killed in action at Gallipoli during the ill- fated Dardinell’s campaign.

He was 37 years old.

The loss devastated the family financially and emotionally.

David’s mother was forced to liquidate the family’s assets to survive.

The young David later reflected on this loss with characteristic understatement, writing that his father had been slaughtered during the war to end all wars.

The absence of a father figure would shape the boy in profound ways, instilling both a deep respect for military service and a rebellious streak that would manifest throughout his youth.

Following her husband’s death, Henrietta Nan remarried in 1917.

Her new husband was Sir Thomas Kman Platt, a conservative politician and diplomat.

The relationship between David and his stepfather was by all accounts deeply antagonistic.

Both David and his beloved sister Grielle harbored an intense dislike for Common Platt.

There has long been speculation, though never proven, that Common Platt may have been conducting an affair with Henrietta before her first husband’s death.

and some have even suggested he might have been David’s biological father.

David’s childhood was marked by frequent upheaval.

The family moved from their London home to Rose Cottage in Benbridge on the aisle of White.

Young David was, by his own admission, something of a tear away.

His propensity for practical jokes and general mischief proved too much for Heather Down Preparatory School from which he was eventually expelled at the age of 10.

He subsequently attended Stow School before securing a place at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

The young Nan arrived at Sandhurst in 1928, and here he found his footing.

The academy that had trained generations of British Army officers proved the ideal environment for channeling his energy and rebelliousness into more productive pursuits.

He did well at Sandhurst, cultivating what would become his trademark bearing, that of the quintessential officer and gentleman.

It was a persona that would serve him well both on the battlefield and on the silver screen.

The agitant at Sandhurst during Nan’s time, there was Major Frederick Arthur Montigue Boy Browning of the Grenadier Guards.

This was a man who would go on to command the British First Airborne Division and First Airborne Corps during the Second World War and whose fate would become intertwined with one of the war’s most audacious operations, the assault on Arnum.

It was a curious coincidence that Nan’s military education should have been overseen by a man who would later play such a pivotal role in airborne warfare.

Meanwhile, his company commander was Major Godwin Austin of the South Wales borderers.

Major Godwin Austin came from a family with deep connections to the 24th regiment of foot.

His uncle, leftinant Frederick Godwin Austin, had been killed at the battle of Icelandana in 1879, commanding G Company of the second battalion.

Here was another thread connecting Nan to that distant catastrophe in Zuluand.

With his cadet ship nearing completion, David Nan faced the pivotal decision of which regiment to join.

His mother, ever mindful of the family’s Scottish ancestry, was eager for him to apply to the Argyle and Southerntherland Highlanders.

The application process required candidates to list their three preferred regiments in order of preference.

With typical irreverence, Nan placed the Argyle and Southerntherlands first, followed by the Black Watch, another distinguished Highland regiment.

For his third choice, the young cadet wrote, “Anything but the Highland Light Infantry.

” The reasoning, as Nan later explained in his autobiography, the moon’s a balloon, was that the Highland Light Infantry wore tartan trus rather than kilts.

It was a comical response to a serious military application, the sort of small rebellion that brought a smile to the perpetrator’s face.

Someone in the corridors of military bureaucracy, however, possessed their own sense of humor.

Having completed his training, David Nan was commissioned as a second leftant in the British Army on the 30th of January 1930.

His assignment, the Highland Light Infantry.

Second leftant Nan joined the second battalion of the Highland Light Infantry, then stationed at Malta.

The Mediterranean posting might have seemed glamorous on paper, but the reality of peacetime garrison duty quickly pulled for a young man of Nan’s restless temperament.

In Malta, however, he forged friendships that would prove significant.

He was befriended by the agitant, Captain Roy Urkhart.

Urkart was another of those characters from Nan’s life who would rise to prominence during the Second World War.

He would go on to command the British first airborne division at Arnham in September 1944, attempting to hold that now legendary bridge against overwhelming German forces.

Ukart later served as general officer commanding during the Malayan emergency.

Nan also became close friends with a fellow officer named Michael Trubsh Shawi, a maverick character who would feature prominently in Nan’s memoirs and who would serve as best man at his first wedding.

The two shared a taste for adventure and an impatience with the tedium of peaceime soldiering.

The monotony of garrison life in Malta proved almost unbearable for the young officer.

Promotion prospects were virtually non-existent and Nan found himself questioning whether the army was truly his calling.

The death of his mother in 1932 dealt another blow.

Henrietta Nan passed away aged 54.

David was granted 4 weeks compassionate leave and on impulse decided to travel to America.

The United States captivated him immediately.

The country seemed to buzz with opportunity and excitement, a far cry from the staltifying routine of military duty in Malta.

Yet duty called him back and Nan returned to his regiment, receiving his promotion to leftenant on the 1st of January 1933.

The promotion, however, did nothing to dampen his growing desire to escape the army.

When the second battalion was posted back to Dover in England, Nan saw his opportunity.

The tedium continued unabated.

The final straw came during a lengthy lecture on machine guns delivered by a major general.

The lecture was interfering with Nan’s plans to dine with a particularly attractive young lady.

At the conclusion of the presentation, when the major general asked if there were any questions, Lieutenant Nan stood and asked, “Could you tell me the time, sir? I have to catch a train.

” It was the sort of impudent question that might have ended a military career abruptly.

Instead, it merely confirmed what Nan already knew.

He was not cut out for peacetime soldiering.

Booking passage across the Atlantic once more, leftant David Nan resigned his commission via telegram whilst halfway across the ocean.

The date was the 6th of September 1933.

He was 23 years old and Hollywood was waiting.

The 1930s represented what many consider the golden age of Hollywood cinema.

The major studios wielded enormous power and a new breed of British actors was beginning to make its mark on the American film industry.

It was into this world that the former left and nan now ventured.

His arrival in Hollywood was not immediately auspicious.

After a series of false starts, including various odd jobs that ranged from promoting indoor horse racing to working as a whiskey salesman, Nan found his way to the film studios.

His first acting role was as an extra, earning $2.

50 a day playing a Mexican.

It was a far cry from the officer class, but it was a beginning.

Through a fortunate encounter, he secured a non-speaking part in the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Lorton and Clark Gable.

It was from this film that Nan first came to the attention of the legendary film producer Samuel Goldwin.

The mogul saw something in the charming young Englishman with the military bearing and signed him to a contract.

Over the next few years, Nan worked his way steadily up through the Hollywood system.

He was lent to Metro Goldwin Mayor for a minor part in Rosemary in 1936, followed by a larger role in Palm Springs for Paramount Pictures.

His first sizable role for Goldwin came in Dodsworth that same year.

1936 proved a breakout year.

Nan was loaned to 20th Century Fox to play Bertie Worster in Thank You Jeeves before landing a significant role alongside his housemate and close friend Errol Flynn in The Charge of the Light Brigade at Warner Brothers.

The film, a swashbuckling imperial adventure, showcased Nan’s natural screen presence and his ability to portray military officers with convincing authority.

If modern audiences sometimes lament Hollywood’s cavalier approach to historical accuracy, they need only watch The Charge of the Light Brigade to see how liberally the studios of the 1930s treated history.

Nevertheless, it was a good old-fashioned adventure film, precisely the sort of entertainment audiences craved, and Nan acquitted himself admirably.

His personal life during this period was equally colorful.

He was romantically involved with actress Merl Oberon and found himself part of a tight-knit community of British expatriots who would become known as the Hollywood Raj.

This informal group included such luminaries as Basil Wthbone, Rex Harrison, Leslie Howard, Ronald Coleman, Boris Caroff, and Olivia De Havland.

They represented a new wave of sophisticated British talent that was coming to dominate certain genres of Hollywood filmm.

Nan’s big break came in 1938 with Dawn Patrol, a fighter pilot drama set during the First World War.

Once again starring alongside Errol Flynn and joined by British actor Basil Wthbone.

Nan delivered a performance that established him as a leading man in his own right.

His portrayal of a Royal Flying Corps pilot seemed almost prophetically linked to his own imminent return to military service.

By 1939, Nan was firmly established among Hollywood’s elite.

His natural charm, impeccable comic timing, and that indefinable quality of Englishness made him a valuable property for the studios.

He appeared in Wthering Heights that year playing Edgar Linton opposite Lawrence Olivier and Merl Oberon and followed it with the title role in Raffles playing the gentleman thief with characteristic a plum.

The golden age however was about to be shattered by events half a world away.

On Sunday the 3rd of September 1939, David Nan was aboard a yacht off the coast of California when he heard the news that would change everything.

Britain and Germany were once more at war.

The declaration of war forced every British citizen abroad to make a choice.

For the members of the Hollywood Raj, the decision was particularly fraught.

The British embassy advised most actors to remain in America where they could continue making films that would support the British cause through propaganda and by generating goodwill among American audiences.

It was in many ways the sensible option, the comfortable option.

David Nan chose differently.

He informed Samuel Goldwin that he had been called up for military service.

The WY producer, smelling a ruse, immediately telephoned the British embassy and ascertained that no such callup had occurred.

Goldwin refused to release one of his leading British stars.

Ever resourceful, Nivean then prevailed upon his brother to send a cable supposedly from the Highland Light Infantry bearing the message, “Report regimental depot immediately.

” Agitant.

The ploy worked.

Goldwin grudgingly allowed David Nan to depart.

It was a remarkable decision.

At a time when his career was flourishing, when wealth and fame were assured, Nan voluntarily gave up everything to serve his country.

He became the only major British star in Hollywood to return home and enlist.

While traveling via Washington, D.

C.

, Nan was invited to meet the British ambassador, Lord Lothian.

The ambassador attempted to dissuade him, arguing that Nan could represent his country far more effectively on the screen than on the battlefield.

It was an argument that most of the Hollywood Raj would accept.

Nan, however, was adamant.

He wanted to serve in uniform.

His first choice was the Royal Air Force.

His recent role as a fighter pilot in Dawn Patrol had fired his imagination, and he harbored dreams of flying Spitfires against the Luftwaffer.

Unfortunately, that very role counted against him.

The Royal Air Force was a wash with potential recruits in those early months of the war, and the last thing many officers wanted was a pretend airman in their midst.

Nan was unceremoniously rejected.

It was a blow to his pride.

But Nan was not so easily defeated.

While nursing his wounded feelings at the cafe de Paris in London, he encountered an officer from the rifle brigade who offered to help him secure a commission in that distinguished regiment.

On the 25th of February 1940, David Nan was recommissioned into the British army as a leftenant in the rifle brigade.

He was assigned to a motor training battalion.

For a man seeking action, it was disappointingly mundane, but it was a beginning.

Shortly after his recommissioning, Nan attended a dinner party where he encountered the first Lord of the Admiral, Winston Churchill.

The future prime minister walked over to him, fixed him with that famous bulldog gaze, and declared, “Young man, you did a very fine thing to give up a most promising career to fight for your country.

” Nan glowed with pride at the compliment.

Then Churchill added, “Mark, you! Had you not done so, it would have been despicable.

” With that, the man who would shortly lead Britain through its darkest hour stalked off, leaving Nan somewhat deflated.

It was a quintessentially Churchillian moment.

Generous praise followed by a sting in the tale.

The first months of the war brought frustration for many British servicemen.

While the first battalion of the rifle brigade fought the Germans in France and would ultimately be lost in the desperate defense of Calala, the second battalion to which Nan was attached remained in England, conducting transport training on Ssbury plane.

The defeat in France and the miraculous evacuation from Dunkirk in May and June of 1940 transformed the strategic situation entirely.

Britain now stood alone against Nazi Germany and invasion seemed imminent.

It was in this atmosphere of crisis that a cryptic message circulated among officers.

Volunteers were required for something special.

Nan and his fellow officers speculated that the something special might involve emulating the German parachute troops who had achieved such remarkable success during the invasion of the Low Countries.

Nan was not especially keen on jumping out of airplanes, but anything seemed more exciting than driving trucks around Ssbury plane.

He volunteered.

What he had actually volunteered for was not the parachute regiment, but the newly formed commandos.

In June 1940, Leftinant David Nan arrived in the Scottish Highlands to begin his commando training at Invar Lord House.

The training was designed to produce soldiers capable of conducting raids, reconnaissance, and sabotage operations behind enemy lines.

It was physically demanding, psychologically challenging, and precisely the sort of adventure Nan had been seeking.

The instructors and fellow trainees included men who would become legends of British special forces.

David Sterling, who would go on to found the special air service.

Mad Mike Calvert, a future Chindit commander under Order Windgate, Simon Fraser, Lord Levat, who would lead the commandos ashore on D-Day.

These were men of extraordinary courage and unconventional thinking, and Nan found himself in his element.

Nan later claimed credit for bringing future Major General Sir Robert Lok to the commandos, though the precise nature of his role in this remains unclear.

The newly trained commando participated in Operation Ambassador, the second ever commando raid of the war.

The target was the German occupied channel island of Gernzi.

The operation conducted in July 1940 was not an unqualified success, but it provided valuable experience and demonstrated that Britain was not content merely to defend.

As the war progressed and the threat of immediate invasion receded, Nan’s career took another turn.

He was transferred to the GHQ liaison regiment, a unit that would come to be known by the evocative code name Phantom.

The Phantom Regiment had its origins in the chaos of the Battle of France in May 1940.

During those desperate weeks, it had become painfully apparent that the modern battlefield was fastm moving and fluid.

Commanders frequently lost contact with their forward units.

Without accurate information about the positions of their own troops and the enemy, effective command was impossible.

The Phantom units were designed to solve this problem.

They consisted of highly mobile officer patrols equipped with wireless sets, motorbikes, and even carrier pigeons.

Their task was to travel in forward areas, sometimes behind enemy lines, monitoring troop movements, listening to Allied and enemy radio communications, and reporting directly back to high command.

They were, in essence, the eyes and ears of the generals.

The regiment recruited men with diverse talents, linguists, drivers, mechanics, radio operators.

Training was rigorous with particular emphasis on wireless communication and cipher work.

The regiment’s headquarters were established at the Richmond Hill Hotel in Richmond, Surrey with the officers mess and billets at Pemroke Lodge in Richmond Park.

Promoted to the rank of major, David Nan was given command of a squadron.

It was a position of considerable responsibility.

The information gathered by Phantom patrols could determine the success or failure of military operations.

Initially, with Britain still bracing for a German invasion that never came, Phantom was deployed in a defensive capacity.

Nan and A squadron found themselves based behind the coastal port of P in Dorset, attached to VCOR.

The core commander for whom they served as eyes and ears was none other than General Bernard Law Montgomery, the man who would later lead the 8th Army to victory at Elamagne and command all allied ground forces during the D-Day landings.

The period from 1940 to 1944 saw Nan juggling his military duties with occasional film work.

The British government recognized the propaganda value of cinema and Nan was permitted to appear in two films designed to boost morale and win support for the British war effort particularly in the United States.

The first of the few in 1942 told the story of Reginald Joseph Mitchell, the designer of the Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft.

Nan played Jeffrey Crisp, a test pilot with Leslie Howard directing and starring as Mitchell.

The film was a pan to British ingenuity and courage released at a time when the Spitfire had become a symbol of national resistance.

The Way Ahead in 1944, also known as the immortal battalion, depicted the transformation of a group of civilian conscripts into soldiers.

The film was made with the full cooperation of the British Army and featured realistic training sequences.

It remains one of the finest British war films ever made and Nan’s central performance demonstrated that his acting abilities had only deepened during his years in uniform.

During his war service, Nan’s Batman was a young private named Peteroff who would himself go on to considerable fame as an actor.

The relationship between the patrician officer and the gifted enlisted man provided material for many amusing anecdotes.

Nan continued to encounter Winston Churchill at various dinners throughout the war.

He recalled a meeting in late 1941 when he asked the prime minister whether America would ever enter the conflict.

Churchill responded enigmatically that something cataclysmic would occur soon.

Just weeks later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into the war.

When Nan later asked Churchill how he had known, the prime minister replied simply, “Because young man, [clears throat] I study history.

” By early 1944, with the Allied invasion of Normandy imminent, Nan’s role shifted again.

He was secounded out of Phantom and with the rank of leftinant colonel began working for American General Ray Barker at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

Barker’s task and therefore Nans was to prevent the sort of miscommunication between allies that had plagued British and French operations in the First World War.

In this conflict, the principal challenge was building effective working relationships between British and American forces.

The personalities involved made this no easy task.

Nan later described how the 54year-old Barker and his team had their work cut out managing the egos of Omar Bradley, Bernard Montgomery, and George Patton.

Nan called them with characteristic wit those super primadonas.

Nan also played a role in operation copperhead, one of the more audacious deception operations of the war.

The plan involved using an actor Mrick Edward Clifton James to impersonate Field Marshall Montgomery in order to confuse German intelligence about the timing and location of the invasion.

Nan helped arrange for Clifton James to study Montgomery’s mannerisms and speech patterns.

The operation helped convince the Germans that the invasion might come through the Mediterranean rather than northern France.

On the 6th of June 1944, the Allied forces landed on the beaches of Normandy.

D-Day had arrived.

David Nan came ashore onto the Normandy beaches several days after D-Day.

Unlike the assault troops who had faced withering fire on the 6th of June, his arrival was less dramatic, but no less important.

His role was to liaz between British and American forces, ensuring that the alliance that had brought millions of men across the English Channel functioned effectively.

It was dangerous work nonetheless.

On one occasion, Nan had to cross between British and American lines on an exposed bridge while German artillery shells fell around him.

Having made the crossing once, he then had to make the journey in reverse.

The Sang Freud that would later characterize his screen performances was forged in moments such as these.

Phantom patrols, including those under Nan’s former command, played a crucial role throughout the Normandy campaign.

They reported on the positions of Allied units, tracked German armor movements, and provided vital intelligence that helped commanders make timely decisions.

The patrols were among the first to report on the closing of the falet’s gap, the encirclement that trapped and destroyed a significant portion of the German forces in Normandy.

Despite being an accomplished raon who delighted dinner parties with elaborate stories, Nan maintained an almost complete silence about his combat experiences.

He had particular scorn for war correspondents who wrote Florida pros about their meager experiences near the front lines.

Anyone who says a bullet sings past, hums past, flies, pings, or whines past, has never heard one, Nan stated bluntly.

They go crack.

It was one of the few specific details he ever shared about being under fire.

As the Allied forces broke out of Normandy and swept across France, Nan continued his liaison work while occasionally finding himself in harm’s way through circumstances rather than design.

One such incident occurred following the liberation of Belgium.

Nan followed Canadian forces into the newly liberated city of Bruge.

Finding a restaurant in the city center, he and a fellow officer decided to sit down and enjoy a civilized meal.

It seemed a reasonable thing to do in a liberated city.

As they emerged from the restaurant, they encountered a Canadian patrol whose members were distinctly alarmed to see British officers strolling about.

The patrol informed Nivean that he needed to evacuate immediately.

The Germans had launched a counteroffensive.

Just half an hour later, enemy forces had retaken the city center.

It was a narrow escape that owed more to luck than military judgment.

The winter of 1944 brought the greatest German counteroffensive in the West, the Battle of the Bulge.

Beginning on the 16th of December 1944, German forces struck through the Ardens, catching the Allies by surprise and threatening to split the British and American armies.

Nan found himself caught up in the chaos.

As he drove through the confusion of retreating American units during the initial German advance, he encountered trouble, though not from the enemy.

Part of the German initial success derived from Operation Grife, in which German soldiers wearing American uniforms and driving American vehicles infiltrated behind Allied lines.

They cut communication cables, changed road signs, and spread confusion and panic.

In the ensuing atmosphere of paranoia, any man in an unfamiliar uniform was viewed with deep suspicion.

American military policemen began questioning everyone, demanding answers to questions about baseball, American popular culture, and other subjects that only a genuine American could answer.

A British officer in British uniform, claiming to be a British leftenant colonel, was under these circumstances highly suspicious.

A patrol stopped Nan and demanded at gunpoint that he prove he was not a German infiltrator by telling them who had won the 1940 World Series.

Nan ever the gentleman replied with characteristic applom.

I haven’t the faintest idea but I do know I made a picture with Ginger Rogers in 1938.

Recognition dawned on the faces of the trigger happy soldiers.

The Debonire film star was allowed to proceed.

All smiles.

Phantom patrols proved invaluable during the Battle of the Bulge, tracking the movement of German armored units and helping commanders understand a chaotic situation.

The intelligence they provided helped the Allies recover from the initial shock and eventually defeat the offensive.

As the Allies advanced into Germany itself in early 1945, phantom patrols provided some of the first reports on what they found.

the concentration camps.

The horror of the Nazi regime was laid bare before their eyes.

Nan, like many veterans, rarely spoke of what he witnessed.

On the 25th of April, 1945, American and Soviet forces linked up for the first time at the Ela River.

A phantom patrol attached to the United States first army was present at this historic moment.

Witnessing and reporting on the meeting of the two great armies that had crushed Nazi Germany from east and west.

Nan gave very few details of his experiences entering Germany with the occupation forces.

His autobiography, the moon’s a balloon, contains only brief references to his conversations with Winston Churchill, the bombing of London, and glimpses of a defeated Germany.

He did however share one story that explained his lifelong reticence about the war.

Some American friends had asked him to search out the grave of their son near Baston, the Belgian town that had been the focal point of the American defense during the Battle of the Bulge.

I found it where they told me I would, Nan later wrote.

But it was among 27,000 others.

And I told myself that here, Nan, were 27,000 reasons why you should keep your mouth shut after the war.

It was a statement of humility from a man who had seen too much to treat war as entertainment.

At the war’s end, Leftinant Colonel David Nan was demobilized.

He joined 15,000 American servicemen heading home across the Atlantic aboard the RMS Queen Mary, but not before General Barker had pinned the United States Legion of Merit on his chest, recognizing his invaluable service in fostering Allied cooperation.

The war had changed him.

The young man, who had resigned his commission via telegram because a lecture interfered with a dinner date, had become a seasoned soldier who had witnessed both the best and worst of humanity.

That experience would inform everything that followed.

While still serving in the military, David Nan’s personal life had undergone a transformation as dramatic as anything in his professional career.

In 1940, while on leave, he met Primula Susan Rolo, known to all as Primie.

She was born on the 18th of February 1918, the only daughter of flight leftant William Rolo and Lady Kathleen Rolo.

Her aristocratic credentials were impeccable.

She was the great niece of Lord Rolo of Duncrub Castle in Scotland and the granddaughter of the Marquest of Dancher.

Primy was a member of the women’s auxiliary air force when she met Nan.

The attraction was immediate and overwhelming.

After a whirlwind romance of just 17 days, David Nan married Premier Susan Rolo on the 16th of September 1940.

The wedding took place at St.

Nicholas Church in Huish, Wiltshire near Primy’s family home at Cold Blow.

The choir of the city of London school sang during the service and Primie dressed in blue was given away by her father.

Michael Troushaw served as best man.

The reception was held at Cold Blow and was attended by various lords, ladies and gentlemen.

The newlyweds settled in a thatched cottage near the village of Dorny on the tempames not far from a hawker aircraft factory where Pry worked as a benchand contributing to the war effort by helping build the aircraft that would defend Britain.

Their first son David Nan Jr.

was born in December 1942.

A second son, James Graham Nan, arrived on the 6th of November 1945, just months after the wars end.

The family seemed blessed.

Friends remembered Pimemy as an absolute delight.

John Mills, the distinguished actor, recalled, “She was a glorious creature, rather aristocratic, but evidently terribly proud of him, very much in love, and always happy to let him be the star turn.

” Tubsha, Nan’s best man, described her as the perfect English rose, kind, fun, and the most wonderful mother for the short time she was allowed.

Clark Gable, who had become one of Nan’s closest friends during the 1930s, and who stayed with the family during his own wartime service in England, grew close to both David and Primie.

It was a friendship that would prove significant in the tragedy to come.

Following the war, Nan resumed his film career.

He returned to Hollywood initially through British productions.

A matter of life and death in 1946, directed by the legendary team of Michael Powell and Emirick Pressberger cast him as squadron leader Peter Carter, a Royal Air Force pilot who survives a crash and must argue for his life in a celestial court.

The film was critically acclaimed, hugely popular in Britain and selected as the first royal film performance.

It remains one of the finest British films ever made.

Samuel Goldwin was eager to reclaim his star.

Nan returned to Hollywood and the family relocated to California in early 1946.

Prim was enchanted by her new surroundings.

The couple bought a home next to their friend Douglas Fairbanks Jr.

which they were renovating while renting another property in Beverly Hills.

6 weeks after arriving in America, tragedy struck on Sunday the 19th of May 1946.

The Nans attended a dinner party at the home of Tyrone Power and his wife Annabella.

The guest list included film notables Gene Tierney and [clears throat] her husband Ole Cassini, Richard Green and his wife Patricia Medina, Cesar Romero, and Rex Harrison with his wife Lily Palmer.

After dinner, some of the guests began playing a game of sardines, a variation on hideand seek.

During the game, Primie was searching for hiding places.

She opened a door, believing it led to a closet.

It led instead to a stone staircase descending to the basement.

Prim fell 20 ft down the steps.

She was rushed to hospital, and for a time, it appeared she might recover, but her injuries proved fatal.

On the 21st of May 1946, Premier Susan Nan died of a fractured skull and brain lacerations.

She was 28 years old.

David Nan was devastated.

The darkest period of his life had begun.

He later recalled that he thought for a time that he had gone mad with grief.

Friends rallied around him, but nothing could console him.

Clark Gable, who had lost his own wife, Carol Lombard, in a plane crash in 1942, was particularly supportive.

Nan later wrote that Gable was drawing on his own awful experience to steer me through mine.

Prim was buried at St.

Nicholas Church in Huish, the same church where she had married David just 6 years earlier.

With two young sons to raise and a career to rebuild, Nan threw himself into work.

Goldwin lent him to Universal to play Aaron Burr in Magnificent Doll in 1946, then to Paramount for The Perfect Marriage in 1947, and again for the other love that same year.

Finally, he was cast in a major picture for Goldwin, The Bishop’s Wife, in 1947 alongside Carrie Grant and Loretta Young.

In 1948, Nan was in England filming Bonnie Prince Charlie when fate intervened once more.

One day, he walked onto the set to find a 28-year-old woman he had never seen before sitting in his reserved chair.

“I had never seen anything so beautiful in my life,” he later recalled.

“Tall, slim or hair, uptilted nose, lovely mouth, and the most enormous gray eyes I had ever seen.

I goggled.

I had difficulty swallowing and I had champagne in my knees.

Her name was Hurispina Genberg.

She was a Swedish fashion model who had been married briefly to a wealthy Swedish businessman Carl Gustaf Tesmoden, divorcing him in 1947 after just 18 months.

The attraction was instant and mutual.

After knowing each other for just 10 days, David Nan married Huris Pina Tesmidan at South Kensington Register office on the 14th of January 1948.

Friends and family were concerned.

Even Nan himself had doubts, reportedly telling friends that he was quite possibly making the greatest mistake of my life.

The marriage was conducted with what some saw as indecent haste, and the introduction of a stepmother to two small boys who had so recently lost their mother, was fraught with difficulty.

The marriage would prove complex and at times troubled.

Hudis, unable to pursue her own acting ambitions, reportedly had difficulties adjusting to life as the wife of a famous star.

The relationship between her and Nan sons, particularly Jaime, was often strained.

Yet the marriage endured for 35 years until Nven’s death in the early 1960s.

Hoping to bring greater harmony to the household, the couple adopted two Swedish daughters, Christina, born on the 4th of June 1961, and Fiona, adopted in 1963.

The girls brought joy to Nan, who had always wanted daughters.

The family established homes on the French Riviera and in Switzerland near the fashionable ski resort of Gishtad.

In 1960, the move to Switzerland made Nan a tax exile, which is believed to be the primary reason why he never received official British honors.

Despite his distinguished war service and contribution to British cinema, with his personal life stabilized, if not entirely serene, David Nan embarked on the most successful phase of his screen career.

The war had deepened him as a man and as an actor.

The luch charm remained, but now it was underllayed with a maturity that allowed him to take on more substantial dramatic roles.

The 1950s saw Nan establish himself as one of the most reliable and versatile leading men in Hollywood.

He appeared in The Moon Is Blue in 1953, a comedy that courted controversy for its frank discussion of sex and seduction.

The film was released without the approval of the production code administration and was condemned by the Legion of Decency.

Yet, it proved enormously popular with audiences.

Around the world in 80 days in 1956 provided one of his most beloved roles as Phyious Fog the punctilious English gentleman who wages that he can circumn the globe in the titular time period.

Nan embodied the sort of imperturbable British character that had become his trademark.

The film produced by Michael Todd was a spectacular success winning the Academy Award for best picture.

My Man Godfrey in 1957 saw Nan take on a role previously played by William Powell in the 1936 original.

The remake may not have surpassed its predecessor, but Nan’s performance demonstrated his continuing appeal in sophisticated comedy.

Then came the role that would bring him the highest accolade in his profession.

Separate Tables in 1958 was adapted from two one-act plays by Terrence Ratigan.

Nan played Major David Angus Pollock, a pathetic figure who pretends to a distinguished military background while hiding a shameful secret.

It was a role that could hardly have been more different from Nan’s own genuine war record.

Yet, he brought to it a depth of understanding and compassion that moved audiences and critics alike.

The performance lasted just 23 minutes and 39 seconds of screen time.

It remains the shortest performance ever to win the Academy Award for best actor.

On the night of the 6th of April 1959 at the 31st Academy Awards ceremony held at the RKO Pantageous Theater in Hollywood, David Nan won the Oscar.

It was the crowning achievement of his screen career.

The significance was not lost on anyone.

Here was a man who had given up a flourishing Hollywood career to fight for his country, who had served as a commando and intelligence officer, who had witnessed the horrors of war, now receiving recognition for playing a man who falsely claimed military honors.

The irony was exquisite.

Nan would go on to co-host the 30th, 31st, and 46th Academy Awards ceremonies, becoming one of the most recognizable figures in Hollywood.

Following his Oscar triumph, Nan continued to work prolifically.

The Guns of Navaron in 1961 was a war film that allowed him to draw on his own military experience, albeit in fictionalized form, playing Corporal Miller, an explosives expert.

He was part of an ensemble that included Gregory Peek and Anthony Quinn.

The film was both a critical and commercial success.

The Pink Panther in 1963 introduced him to a new generation of audiences.

Playing Sir Charles Littton, the suave gentleman thief known as the Phantom, Nan demonstrated that his comic timing remained as sharp as ever.

The role earned him a British Academy of Film and Television Arts nomination.

In 1967, Nan took on a role that seemed almost destiny.

He played James Bond in Casino Royale.

Though the film was a comedic parody rather than a straightforward adaptation of Ian Fleming’s novel, Nan’s portrayal of the retired Sir James Bond brought elegance and wit to the production.

It was fitting that the actor who had epitomized British sophistication for three decades should play the most famous fictional embodiment of British cool.

Through the 1970s, Nan continued to work steadily.

Murder by Death in 1976 saw him reunite with an impressive ensemble of veteran actors including Peter Cers, Alec Guinness, and Maggie Smith.

Death on the Nile in 1978, adapted from Agatha Christiey’s novel, cast him alongside Peteroff, the very man who had served as his Batman during the war.

Beyond his film work, Nan achieved remarkable success as an author.

His autobiography, The Moon’s a Balloon, published in 1971, became an international bestseller.

Written with the same charm and wit that characterized his screen persona, the book offered anecdotes from his extraordinary life, though friends and family noted that some stories were embellished in the retelling.

It sold millions of copies worldwide.

A follow-up, Bring on the Empty Horses, appeared in 1975.

The title derived from a malipropism uttered by director Michael Curtis during the filming of the charge of the light brigade.

Curtis, a Hungarian with an imperfect command of English, had called for riderless horses by shouting, “Bring on the empty horses.

” The book offered further reminiscences of Hollywood’s golden age and proved almost as popular as its predecessor.

Nan also wrote novels.

Round the Rugged Rocks appeared in 1978 and Go Slowly, Come Back Quickly was published in 1981.

Neither achieved the success of his memoirs, but they demonstrated his versatility as a writer.

Throughout his life and career, David Nan remained connected to the military heritage that had shaped his family for generations.

That heritage deserves exploration for it illuminates something essential about the man himself.

His maternal grandfather, Captain William Degata, was born William Hitchcock in 1841, educated in France, then at Rugby School and finally at Imperial College London.

He joined the British Army in 1859 and was commissioned into the 24th Regiment of Foot, which later became the South Wales Borderers.

William’s older brother, Henry Dasha, also served with the regiment.

Both brothers, along with their father, Walter Henry Hitchcock, had adopted their mother’s maiden name of Dasha in 1874.

By the time of the Anglo Zulu war in 1879, the two brothers had risen to significant positions.

Leftant Colonel Henry Datcha commanded the second battalion of the 24th Regiment.

Captain William Deatcha serving with the first battalion had been given the Brevitt rank of major for the campaign.

The War of 1879 marked the first time both battalions of the 24th regiment had served together.

It would also mark the most catastrophic day in the regiment’s history.

On the morning of the 22nd of January 1879, the British forces were encamped at East Sandwana beneath a distinctive sphinx-shaped mountain.

Lord Chelmsford, the British commander, had moved out of camp with the second battalion to pursue what he believed was the main Zulu army.

Henry Datcha accompanied Chelmsford.

Only one company of the second battalion G company under the command of leftenant Frederick Godwin Austin remained at Eandlana.

William Deatcha with the first battalion stayed at the camp.

When Chelmsford departed, Colonel Pollain took command of the camp and Brav Major William Deatcha assumed temporary command of the first battalion.

Thus, on the morning of the battle of Eisendwana, both battalions of the 24th regiment were remarkably under the command of brothers Henry away with Chelmsford and William at the camp.

What happened next was the greatest defeat the British army ever suffered at the hands of an indigenous African force.

The main Zulu army of some 20,000 warriors had not pursued Chelmsford.

Instead, they were hidden in a valley near Icelandana, and that morning they launched a devastating assault on the camp.

The British garrison, numbering perhaps 1,700 men, including native auxiliaries, was overwhelmed.

The battle was swift and brutal.

By early afternoon, the camp had fallen.

Over,300 men on the British side perished, including leftenant Frederick Godwin Austin who had commanded G Company and Captain William Datcher, David Nven’s maternal grandfather.

Henrietta Dasha, William’s daughter and David Nian’s mother was born in Breen in 1877, 2 years before her father’s death.

She grew up in the shadow of Isand Lana, the daughter of a man whose bones lay on that distant African plane.

When David Nan arrived at Sandhurst in 1928, his company commander was Major Godwin Austin, the nephew of Lefenant Godwin Austin, who had fallen alongside William Dasha at Eandalwana.

It was a remarkable coincidence, a thread connecting the young cadet to the tragedy that had shaped his family.

Nan himself never starred in either Zulu or Zulu Dawn, the films that dramatized the battles of Ro’s Drift and Eandalana, respectively.

Yet the connection was there embedded in his bloodline, a reminder that military service with all its dangers and sacrifices was his birthright.

This heritage helps explain why when war came in 1939, David Nan felt compelled to serve.

He was not merely a film star playing at soldiers.

He came from a long line of military men stretching back through his father’s death at Gallipoli to his grandfather’s fall at Ice and Dalwana.

Service was in his blood.

By the early 1980s, David Nan had been a fixture of British and American cinema for nearly half a century.

He had made more than 90 films, won an Academy Award, written best-selling books, and become one of the most beloved figures in entertainment.

He had also begun to show signs of a devastating illness.

The first symptoms appeared around 1980.

Nan began experiencing fatigue and muscle weakness.

His voice, that distinctive instrument that had charmed audiences for decades, started to deteriorate.

Initially, there was speculation that he might have had a stroke.

The diagnosis when it came was devastating.

Amotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as motor neurone disease or luger’s disease.

It is a progressive condition that causes the death of neurons controlling voluntary muscles leading to weakness, atrophy, and eventually complete loss of motor function.

There is no cure.

Nan faced his illness with characteristic courage and wit.

He continued to work for as long as he was physically able, appearing in Trail of the Pink Panther in 1982 and Curse of the Pink Panther in 1983.

By the time of these final films, his voice had deteriorated so severely that his dialogue had to be dubbed by another actor, Rich Little.

The decline was visible to all who knew him.

Photographs from his final years showed a man who had become drawn and emaciated.

His weight dropped from 230 lb to just 110 lb.

Friends who visited him at Wellington Hospital in London were moved by his determination to maintain his spirits despite his condition.

Roger Moore, his friend and fellow actor, remained close throughout Nan’s illness.

Their friendship forged through years of working in the same industry was a source of comfort.

In mid July 1983, Nan moved from his home at Caparat in the south of France to his chalet in Chatau Doex in the Swiss Alps.

friends reported that his condition and spirits improved somewhat in the mountain air.

He had always loved Switzerland, and it seemed fitting that he should spend his final days there.

On the morning of the 29th of July 1983, David Nan died peacefully in his sleep.

He was 73 years old.

His nephew Michael Rangdad announced, “My uncle died peacefully and without pain shortly after 7:00 in the morning.

” His last gesture a few minutes before he died had been to give the thumbs up sign.

It was a characteristically nonven farewell, dignified, [clears throat] understated, and with a final gesture of optimism.

Tributes poured in from across the entertainment world.

Gregory Peek described him as the epitome of scintillation and charm.

Marlon Brando called him one of the most compulsively charming men I ever knew.

Roger Moore, writing later of that morning, recalled receiving the news from David Bolton, Nan’s physiootherapist and friend who had been staying at the chalet.

Moore and his daughter immediately raced to shadow dogs.

A memorial service was held at St.

Martin in the Fields in London on the 27th of October 1983.

Audrey Hepburn was among those who attended.

Nan was interred in Shadow Doex, the Swiss village that had been his home for more than two decades.

It was a fitting resting place for a man who had spent his life moving between countries and continents.

His second wife, Teardis, outlived him by 14 years, passing away on the 24th of December, 1997.

What remains of a man when the cameras stop rolling and the final curtain falls? For David Nan, the answer lies not in his Academy Award, his Golden Globes, or his best-selling books.

Though these were remarkable achievements, it lies in the choices he made when the stakes were real.

In 1939, at the height of his Hollywood success, David Nan chose to serve his country.

He was the only major British star in Hollywood to do so.

While others remained in California making films that would admittedly support the war effort in their own way, Nan put on a uniform and placed himself in harm’s way.

He served with the commandos, trained alongside men who would become legends of British special forces.

He commanded reconnaissance patrols that gathered intelligence vital to Allied operations.

He came ashore in Normandy, experienced the chaos of the Battle of the Bulge and witnessed the liberation of Europe.

And yet, despite being one of the finest storytellers of his generation, he maintained an almost complete silence about his war experiences.

He understood that the 27,000 graves at Baston and the countless others scattered across Europe represented sacrifices far greater than his own.

His humility was genuine.

The war shaped him in ways that informed everything that followed.

The man who returned to Hollywood in 1945 was not the same man who had left in 1939.

He had depth now, a gravitas that allowed him to take on dramatic roles alongside his comedic ones.

He had experienced loss, having survived the death of his beloved first wife within weeks of returning to America.

His family connections to military history stretched back generations to his father’s death at Gallipoli, to his grandfather’s fall at Ezandwana.

Service was not for David Nan a matter of patriotic abstraction.

It was personal, woven into the fabric of his family’s story.

And yet he wore his service lightly as he wore everything.

The Debonire charm that audiences loved was not a mask but an essential part of who he was.

He could face German artillery with the same equinimity he brought to a Hollywood premiere and face both with a wit that diffused tension and endeared him to all who knew him.

The thumbs up gesture he gave moments before his death, facing the end of a terminal illness that had stripped him of so much, was quintessentially nan.

neither mlin nor falsely cheerful, simply an acknowledgement that he had lived a good life and was prepared to let it go.

Leftant Colonel James David Graham Nan, recipient of the United States Legion of Merit, Academy Award winner, commando, intelligence officer, memoirist, film star, father of four.

A heck of a career, a heck of a man.

If you have enjoyed this journey through the remarkable life of David Nan, please do subscribe to Cinema Peak and click the notification bell so you never miss a new documentary.

Thank you so much for watching.

I will see you in the next one.

News

1000 steel pellets crushed their Banzai Charge—Japanese soldiers were petrified with terror

11:57 p.m. August 21st, 1942. Captain John Hetlinger crouched behind a muddy ridge on Guadal Canal, watching shadowy figures move…

Japanese Pilots Couldn’t believe a P-38 Shot Down Yamamoto’s Plane From 400 Miles..Until They Saw It

April 18th, 1943, 435 miles from Henderson Field, Guadal Canal, Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto, architect of Pearl Harbor, commander of the…

His B-25 Caught FIRE Before the Target — He Didn’t Pull Up

August 18th, 1943, 200 ft above the Bismar Sea, a B-25 Mitchell streams fire from its left engine, Nel fuel…

The Watchmaker Who Sabotaged Thousands of German Bomb Detonators Without Being Noticed

In a cramped factory somewhere in Nazi occupied Europe between 1942 and 1945, over 2,000 bombs left the production line…

The Priest Who Recorded SS Confessions in the Booth and Sent Them to the Allies

Munich, 1943. The confessional booth of St. Mary’s Church stood in the shadows of the nave, a wooden sanctuary…

FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis Charity — $250M Terror Network & Governor ARRESTED

At 11:47 on a bitter Tuesday morning, federal agents stepped in front of the cameras in Minneapolis and delivered a…

End of content

No more pages to load