Some witnesses are meant to be center stage in history. Others are quietly pushed into the wings. Mr. Brehm was one of the latter. On November 22, 1963, he did not watch the assassination of John F. Kennedy from a distant sidewalk, behind a crowd, or through a camera lens. He stood mere feet away, close enough to see, hear, and feel what happened in Dealey Plaza — and close enough that his account should have been indispensable. Instead, it was effectively ignored.

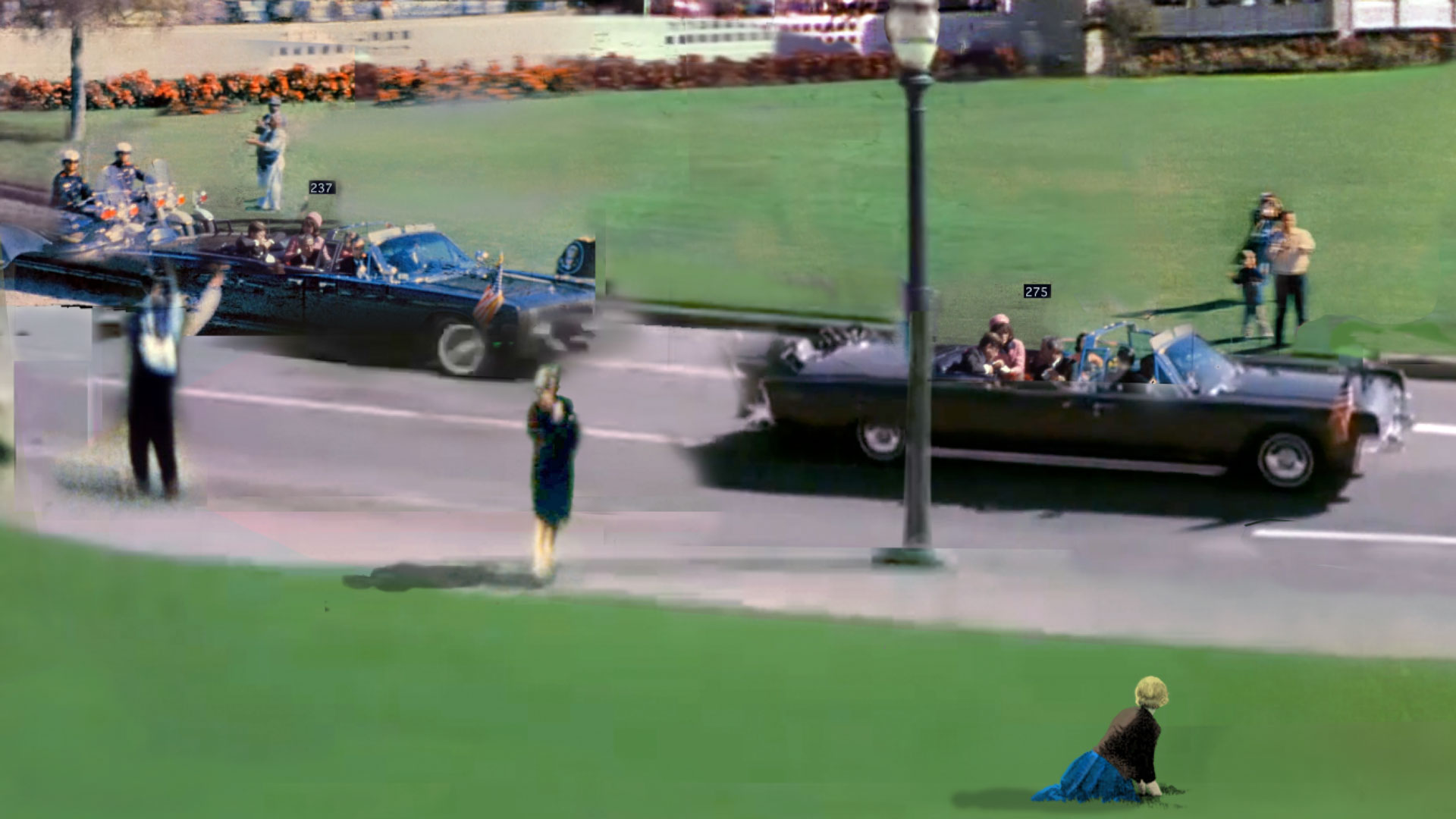

That morning began innocently enough. Brehm, a World War II Ranger who had fought in France and been wounded twice, took his five-year-old son downtown to see the presidential parade. Like thousands of other Dallas residents, he wanted his child to witness history. They stood together on the grass along Elm Street, close to the curb, close to the motorcade, close to a moment that would scar both their lives.

When the limousine came into view, Brehm waved. His son waved. President Kennedy waved back. It was an ordinary exchange, the kind that happens in every parade, every campaign stop, every public appearance. Then the world changed.

The first shot rang out. Brehm did not need to guess what it was. Combat veterans do not forget the sound of a rifle fired nearby. To him, it was unmistakable. He saw Kennedy slump in his seat, his body folding forward. Jacqueline Kennedy reached toward her husband, instinctively reacting to something she could not yet fully comprehend.

Then came the second shot.

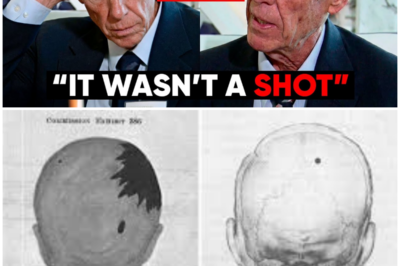

This was the moment that burned itself into Brehm’s memory forever. He saw Kennedy’s hair fly up. He saw the president struck in the head. He saw something no government report would ever truly confront — pieces of skull and brain matter flying backward and to the left, landing near the curb where he stood. He was close enough that he could have been hit by them.

Brehm did not speculate. He did not theorize. He simply described what he saw: debris moving left and backward from the limousine, not forward. To anyone familiar with ballistics, that detail carried enormous implications. It suggested a shot from the front or side, not solely from the rear. But Brehm was not thinking like an investigator that day. He was thinking like a father trying to protect his child. He grabbed his son and threw himself over him, shielding him from what he feared might be more gunfire.

Within minutes, chaos consumed Dealey Plaza. Police, Secret Service agents, and panicked citizens flooded the scene. Brehm, shaken but composed, did what a responsible witness does — he spoke. He told newsmen what he had seen. He explained that two shots had hit the president and described the direction from which he believed the fatal shot came. His words were recorded. His face appeared on television. He was clear, calm, and certain.

Later that day, Brehm voluntarily went to the Dallas Sheriff’s Office and remained there for three to four hours, providing a detailed statement. He was, by his own admission — and by any reasonable measure — one of the closest eyewitnesses to the assassination. If anyone had a clear view, it was him.

And yet, when the Warren Commission convened to investigate the murder of the president, Mr. Brehm was never called to testify.

That absence is not a small oversight. It is a glaring hole.

The Warren Commission interviewed hundreds of witnesses — some far less certain, far less consistent, and far farther from the scene than Brehm. They relied heavily on testimony that supported a single-shooter narrative, often privileging accounts that fit neatly into their conclusions. But Brehm’s testimony did not fit neatly. His description of skull fragments moving left and backward directly contradicted the idea that all shots came from the Texas School Book Depository behind the motorcade.

The question is not whether Brehm told the truth — his military background, demeanor, and consistency make that unlikely — but why his truth was inconvenient.

Brehm was not a conspiracy theorist. He did not claim multiple shooters or hidden plots. He simply reported what his eyes saw and what his instincts, sharpened by war, told him was real. That made him dangerous to a narrative that needed simplicity, certainty, and closure.

In the days and weeks after the assassination, America was desperate for a clean story. One shooter. One rifle. One motive. One explanation. Oswald’s murder two days later eliminated the possibility of a trial, removing the need for rigorous cross-examination of every witness. The Warren Commission’s role shifted from prosecuting a case to constructing an official version of events.

In that environment, witnesses like Brehm became liabilities.

His account was not vague. It was not confused. It was not contradictory. And that was the problem. If the commission had placed him on the stand, his testimony would have forced them to confront uncomfortable physical realities: the direction of debris, the immediate reaction of the president’s body, and the proximity of a man who saw it all unfold from almost ground level.

Instead, Brehm was left out.

Over time, his story faded from public consciousness, buried beneath diagrams, expert analyses, and increasingly polished explanations. But his words never changed. He remained certain that the second shot struck Kennedy in the head and that the debris flew backward and left — toward him.

When historians later revisited eyewitness accounts, Brehm’s testimony aligned with several others who described similar observations. Multiple witnesses near the grassy knoll reported seeing fragments travel in the same direction. Parkland Hospital doctors described massive rear head damage inconsistent with a shot from above and behind. Photographic and physical evidence raised further questions.

Yet Brehm himself remained largely absent from mainstream discussions.

There is something deeply unsettling about that. Not because it proves a conspiracy, but because it reveals how powerfully narratives can be curated. Brehm was not silenced through threats or coercion. He was simply rendered unnecessary.

His story highlights a broader pattern in the JFK investigation: when evidence aligned with the preferred conclusion, it was amplified; when it did not, it was quietly sidelined.

Brehm’s life did not revolve around November 22, 1963. He was a father, a veteran, a man who had already faced death in war. But that day followed him forever. He never forgot the sound of the shots, the sight of Kennedy falling, or the moment he threw himself over his son.

His testimony is not dramatic. It is not theatrical. It is brutally straightforward — and that is precisely what gives it weight.

In the end, the tragedy of Mr. Brehm’s story is not just that he witnessed a president’s murder. It is that his clear, unembellished account was deemed expendable in the crafting of an official history.

And as long as that remains true, the full story of Dealey Plaza will never truly be complete.

News

“They Keep Trying to Silence Me, But I’ll Tell The Truth” JFK Mortician

The night of November 22, 1963 did not end when Air Force One touched down at Andrews, when Lyndon Johnson…

The White House 1600 Sessions: History Revealed: The Kennedy Gravesite

In the shadow of the White House and across the solemn expanse of Arlington National Cemetery lies a story that…

The Secret History of the Kennedys: A Family’s Quest for Power

The Kennedy name has long been synonymous with power, glamour, and the American dream, yet woven through that brilliance is…

A Confession From The Man Who Shot JFK | Confessions Of An Assassin

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy has remained one of the most controversial and disputed events in American history…

A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination

On a cold November day in 1963, the United States lost more than a president — it lost its certainty….

Why Kennedy Refused Eisenhower’s Warning About Vietnam

On the morning of January 19, 1961, a day before his inauguration, John F. Kennedy walked through the northwest gate…

End of content

No more pages to load