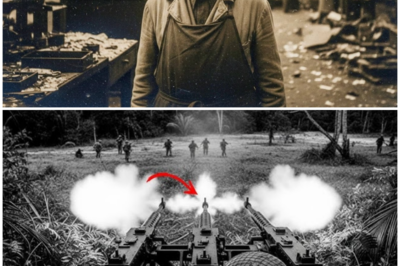

11:57 p.m. August 21st, 1942. Captain John Hetlinger crouched behind a muddy ridge on Guadal Canal, watching shadowy figures move through the jungle mist 200 yd away.

In the damp air, the rustle of leaves mingled with a low murmur of Japanese troops in the distance.

Moisture rose from the rain soaked ground, enveloping the 37 mm anti-tank gun he manned.

The 31-year-old Hetlinger was a US Marine Corps artillery officer.

For months, he had been modifying a weapon never designed to kill infantry, one built to punch through tank armor.

Sergeant McCulla, the gunner, gave the breach a final check and slid a seemingly ordinary round into it.

Inside, though, lay a deadly device the Japanese had never seen.

122 steel pellets the size of marbles packed tightly together, ready to rain down like hellfire.

For months, Japan’s bonsai charges had struck fear into American troops across the Pacific.

Hordes of screaming soldiers, bayonets fixed, charged headlong into battle.

Overwhelming enemies with sheer numbers and fanatical courage.

Every Marine on Guadal Canal had heard the tales.

Hundreds of Japanese troops charging in unison, unstoppable, willing to die for the emperor, dragging battles into brutal hand-to-hand combat that erased America’s firepower advantage.

This tactic, honed on the battlefields of China and the Philippines, broke enemy lines with its cruel simplicity and shattered morale.

That night, more than 1,000 soldiers of Japan’s 17th Infantry Division prepared to launch the largest bonsai charge in Guadal Canal’s history.

They were convinced their age-old tactics would drive the Americans into the sea.

But Hetlinger’s gun was not loaded with its intended armor-piercing rounds.

McCulla had chambered an M2 canister round, turning this tank killer into the deadliest shotgun the world had ever seen.

The round would detonate just beyond the muzzle, unleashing a storm of steel pellets across a 1 to200yd kill zone.

The Japanese troops pouring into the jungle clearing never imagined their greatest strength was about to become their fatal weakness.

6:00 p.

m.

August 21st, Marine scouts deployed along the Lunga River spotted the enemy massing in the dense jungle west of Henderson Field and sent the first report of Japanese movements.

Captain Hetlinger was cleaning his 37 mm gun.

Then the barrel still held the warmth of its afternoon test fire.

The intelligence he received was brief but chilling.

Enemy strength estimated at assault size, possibly more, closing in on American defensive positions eastward under the cover of night.

Lieutenant General Harukichi Hayakutake in his command post in the mountains upstream of the Matanakaw River had been planning this offensive for 3 weeks since US troops had landed on Guadal Canal 6 weeks earlier.

His 17th Infantry Division had suffered constant losses of men and supplies.

Its situation growing increasingly desperate.

Japanese supply convoys could only race to reinforce the island along narrow channel routes by night.

hiding from American bomber patrols by day.

Troops were on half rations.

Many were stricken with malaria and dysentery.

But Hayakotake knew a breakthrough would turn the tide of the war, seize the American positions, recapture Henderson Field, and Japanese warplanes would return to Guadal Canal, altering the course of the entire Solomon Islands campaign.

The Bonsai charge was not born of pure despair.

Rooted in centuries of samurai tradition and modern military doctrine, it exalted spiritual strength above material superiority.

In Japanese infantry training, soldiers were indoctrinated with the belief that a determined assault could overrun any defensive position.

Victory was inevitable so long as they fought bravely with unwavering loyalty to the emperor.

From Nanjing to Manila, this human wave tactic had repeatedly smashed enemy lines, crushing the will of defenders unable to match Japanese fanaticism.

Hayakataki’s officers reported that while the US Marines fought bravely, they had never faced a full-scale bunai charge.

The general was certain that 1,000 soldiers screaming out of the jungle in the dead of night would scatter the defenders like a typhoon blowing away leaves.

Rain dripped through the jungle canopy, turning the ground beneath their feet into black mud.

First Lieutenant Kenji Okatada briefed his company commanders.

Soldiers crouched in the underbrush.

Arisaka Type 38 rifles fixed with bayonets, their faces blackened with charcoal to blend into the night.

Each carried only the bare essentials, rifle and bayonet, two hand grenades, and ammunition for the initial assault.

Speed and surprise were the keys to victory.

Once they broke through the American lines, they would seize captured weapons to continue the offensive.

Okata had fought in China and witnessed this very tactic crushwoman Tang forces.

The terror of Japanese infantry charging with fixed bayonets and the battle cries echoing across the field had sent entire enemy divisions fleeing in panic.

American defensive positions stretched along the ridge overlooking the jungle trails with an interlocking crossfire.

Meticulously planned, they funneled any attack into killing zones.

Captain Hetinger positioned his gun crew at the center of the line, a spot with unique terrain.

Any attacker would have to cross a natural clearing about 150 yards wide, a perfect firing range.

The M337mm anti-tank gun [clears throat] was built to destroy Japanese light tanks and armored vehicles, but such targets were extremely rare in Guadal Canal’s thick jungle terrain.

So, Hetlinger spent weeks testing the M2 canister round, transforming this tank killer into a devastating weapon for infantry combat.

Each canister round held 122 precision machined 38 caliber steel pellets encased in a thin metal shell that burst the moment it left the muzzle.

Upon firing, the pellets formed a massive shotgun-like cone of fire, lethal to masked infantry at ranges up to 250 yards.

The weapon’s direct fire capability allowed the gunner to spot targets and adjust aim directly.

No forward observer or radio coordination needed.

A stark contrast to mortars and artillery against human wave attacks.

No other weapon in the American arsenal could match its mobility, precision, and devastating firepower.

Sergeant McCulla had trained his crew to load and fire by touch and muscle memory in the dark.

Weighing just 900 lb, the gun could be quickly moved and in place by six men.

Yet it was sturdy enough to absorb recoil without losing accuracy round after round.

Private Miller served as the loader responsible for chambering rounds and maintaining ammo supplies during battle.

The crew had test fired at wooden targets at various distances, watching in awe as the steel pellets tore through simulated enemy formations with surgical precision.

Midnight drew near and the sounds of the jungle shifted.

Birds fell silent.

Insects ceased their chirping.

Even the constant drip of water from tree branches seemed to pause.

Marines along the line gave their weapons a final check, staring into the darkness through iron sights and binoculars.

Machine gun crews tested elevation and traverse mechanisms to ensure smooth operation when firing.

Mortar crews calculated distances to pre-planned targets.

Riflemen counted their ammo and made lastminute adjustments to their positions.

10:5 a.

m.

[clears throat] Despite their numbers, the Japanese advanced through the jungle with expert stealth.

Officers issued orders in low whispers.

Companies spread out into attack formation, their lines stretching nearly half a mile wide, maximizing the psychological impact of the charge.

The plan called for simultaneous attacks on multiple points of the American line, preventing defenders from concentrating fire and sewing chaos for follow-up troops to exploit.

Okatada positioned his regiment at the center of the assault, directly facing Hetlinger’s gun imp placement.

In the dark, neither man knew the other was there.

The first sign of the storm came as a low rumble, gradually sharpening into the unison cry of hundreds of Japanese troops.

The sound grew louder as the soldiers worked themselves into the psychological state needed for a suicide charge.

American outpost reported enemy movement along the entire line.

Shadowy figures moved between the trees in the dark.

No longer attempting to hide, the stealth phase was over.

Now spiritual strength was about to collide headon with American steel.

Centuries of samurai tradition would clash violently with modern military technology.

This confrontation would decide the fate of Guadal Canal and possibly the entire Pacific War.

3 months earlier, this M337 mm anti-tank gun had left the Rock Island arsenal in Illinois bound for Guadal Canal.

Engineers had designed the weapon specifically to punch through the armor of Japan’s Type 95 Hago light tanks.

Its semi-automatic breach mechanism allowed a well-trained crew to fire 15 rounds per minute.

With standard armor-piercing rounds, it could penetrate 25 mm of steel plate at 500 yd.

More than enough to destroy Japan’s thin skinned tanks across the Pacific.

Captain Hetlinger first encountered the M2 canister round during training at Camp Lun in North Carolina.

instructors had demonstrated its effectiveness against simulated infantry attacks.

The round measured 3 in in diameter and 4.

7 in in length, weighed 2 lb, and packed those deadly steel pellets inside a precision engineered metal shell.

Fired, it traveled about 50 ft before a time fuse triggered the shell to burst, sending the pellets flying in a widening cone 30 yard wide at its maximum effective range.

Each pellet weighed about a third of an ounce, traveling at nearly 1,500 ft per second.

Their kinetic energy was enough to punch through human flesh and bone with devastating force.

The concept of canister fire dated back to 18th century warfare when artillery crews loaded cannons with grapeshot to shatter masked infantry.

American ordinance experts studied combat records of grapeshot from the Civil War, notably at the Battle of Gettysburg, where Union artillery used it to decimate Confederate charges in open ground.

The M2 canister round refined this early design, replacing irregular iron fragments with precision machine steel pellets to ensure stable ballistics and even dispersion.

Quality control at Detroit manufacturing plants required each pellet to be machined to a tolerance of 0.

002 in guaranteeing consistent flight paths upon firing.

Sergeant McCulla knew the weapon’s power better than most.

Before deploying to the Pacific, he had served as an artillery instructor.

He calculated that at the optimal range and angle, firing one canister round at a formation of soldiers standing 6 f feet apart could kill or wound every man in a 60-yard wide front.

The pellets retained lethal velocity out to 200 yd, but beyond 150 yards, air resistance and gravity took their toll, diminishing accuracy significantly.

To maximize casualties against infantry, McCulla preferred to fire at 75 to 125 yards, a range where the pellet cone remained dense while covering a large enough area to decimate mass attacks.

Unlike mortars and howitzers, the M3’s direct fire capability gave it a decisive advantage against visible targets.

No complex calculations, no forward observers needed to adjust fall of shot.

The gunner aimed directly through an optical sight mounted above the barrel.

The sight assembly included range markings for both armor-piercing and canister rounds, allowing quick adjustments for wind and elevation in combat.

In daylight, a skilled gunner could place rounds within 3 yards of their target at 300 yard.

But in the dark, with no artificial illumination, accuracy dropped dramatically.

Private Miller had memorized the loading procedure so thoroughly he could perform it blindfolded, a critical skill in the chaos of night combat.

Each two-lb canister round had to be handled with care to avoid damaging its fragile metal shell.

When fired, the semi-automatic breach let out a sharp metallic clatter, ejecting the empty casing to allow instant reloading.

In sustained combat, Miller could maintain a rate of fire of 12 rounds per minute, but the crew typically fired in bursts of three to five rounds to prevent barrel overheating and conserve ammo.

Logistical challenges with ammo supply had plagued Captain Hetinger since arriving on Guadal Canal.

Each gun imp placement stockpiled 50 mixed rounds, 30 canister, 20 armorpiercing stored in waterproof buried containers near the position.

Resupplying during battle required ammo carriers to ferry single rounds from an ammo dump 200 yards away.

A perilous journey across ground rad by enemy fire.

The weight and bulk of 37 mm ammo meant each marine could carry only two rounds at a time.

Sustained fire depended on precise ammo management and shooting accuracy.

Japanese intelligence had failed to detect the anti-tank guns in the American defensive line.

Their focus fixed on the more obvious threats to infantry attacks, machine gun nests and mortar positions, enemy reconnaissance patrols watched roads and marines digging in along the ridge, but missed the well- camouflaged 37 mm guns aimed at key approach routes.

Hiakataki’s battle plan assumed his soldiers would face only rifle and light machine gun fire during their charge, threats they could overcome with speed and resolve.

Nowhere in their tactical calculations had they anticipated the devastating firepower of canister rounds.

In the weeks leading up to the attack, Hetlinger’s crew had drilled the firing procedure countless times, striving for split-second coordination for the moment hundreds of enemy troops burst from the jungle at once.

McCulla was the gunner responsible for aiming and firing.

Miller loaded the rounds and coordinated with ammo carriers.

Two other Marines served as ammo bearsers, stationed in a shallow trench 10 yards behind the gun, watching the tactical situation and fing rounds as needed.

A fifth crew member operated a soundpowered telephone, linking to Hetlinger’s command post, coordinating with other weapons and calling for artillery support if needed.

The weapon’s greatest limitation was its inability to fire over obstacles or provide indirect support to distant positions.

Unlike mortars, which could lob rounds over hills and trees, the 37 mm gun needed a clear line of sight to hit targets effectively.

This meant Japanese soldiers who closed in on dead spots in the American line would be safe from canister fire.

Thus, the weapon had to work in tandem with other defensive systems to reach its full potential.

Hetlinger positioned the gun in the open clearing, forcing attacking Japanese troops into the open while machine guns and rifles covered the blind spots the anti-tank gun could not reach.

In the darkness ahead, the Japanese cries grew louder.

McCulla made final adjustments to the gun’s elevation and traverse, ensuring smooth operation when the order to fire came.

The first canister round was chambered, ready to fire.

Miller crouched beside the ammo pile, loading gloves on, poised for action.

Hetlinger patrolled between gun imp placements, checking communications, ensuring each crew knew their sector of fire.

A weapon built to destroy tanks was about to face its greatest test against an enemy that believed spiritual strength could overcome any material advantage.

Number 127 a.

m.

First Lieutenant Okada raised his sword and shouted the traditional charge cry, his voice echoing across the jungle clearing.

More than 1,000 Japanese troops burst from the trees at once, their screams merging into a terrifying chorus.

A sound that had shattered enemy formations from Manuria to the Philippines.

The soundwave rolled across the dark battlefield like thunder.

A primal roar from soldiers who had accepted death.

Their only wish to take as many enemies with them as possible.

Bayonets glinted in the faint starlight.

The human waves surged forward.

boots splashing through mud and shallow puddles, closing in on the American positions.

Hetlinger watched the assault unfold through binoculars, counting the endless stream of enemy troops pouring from the jungle.

The Japanese had formed a formation 300 yd wide and 20 ranks deep.

Officers were scattered throughout the lines to maintain direction and momentum.

Front rank soldiers brandished rifles with fixed bayonets.

Those behind wielded swords, grenades, even sharpened bamboo spears.

The scale of the attack was nearly 50% larger than American intelligence had estimated.

The largest concentration of enemy infantry US forces had faced on Guad Canal.

McCulla tracked the advancing horde through the gun site, waiting for the enemy to enter the pre-planned engagement range of 125 yards.

In the dark, Japanese soldiers stumbled and fell, but kept moving forward without pause, even trampling their own wounded in their desperate charge toward the Marine lines.

As the front rank of enemy troops closed to half the distance of the American line, McCulla’s finger tensed on the trigger, making final aim adjustments, he corrected the elevation slightly to account for the gentle downward slope of the terrain.

The lead Japanese soldiers had begun to scream, guttural words and constant cries hsening their voices, but doing nothing to slow their advance.

First Lieutenant Okata ran among his soldiers, sword held high above his head, urging his men forward.

Even as machine guns on the ridge opened fire with a staccato crack, red tracers cutting through the dark and mowing down the front ranks, Japan’s numerical advantage filled the gaps instantly with more troops from the rear.

They stepped over the bodies of fallen comrades and pressed on.

At exactly 120 yards, McCulla squeezed the trigger.

He felt the brutal recoil of the 37 mm gun slam the weapon back.

A burst of flame lit up the jungle clearing for an instant, revealing hundreds of enemy faces contorted with battle frenzy before the canister round burst 50 ft from the muzzle, unleashing its deadly payload.

122 steel pellets flew in a devastating cone at 1,500 ft per second, slamming into the tightly packed Japanese formation.

The effect was immediate and horrific.

Japanese soldiers in the center of the assault formation vanished in an instant.

Multiple pellets tearing through flesh and bone with lethal force, knocking them to the ground.

Soldiers running at full speed crumpled midstride, their momentum sliding their bodies across the mud for yards before they came to a halt.

The cone of destruction tore a 30yard wide gap in the front ranks.

Dead and wounded soldiers lay scattered across the jungle floor like broken dolls.

Miller had the second canister round ready.

The empty casing clattered to the ground beside the gun and he slammed the new round into the brereech.

The semi-automatic mechanism worked flawlessly.

McCulla adjusted his aim slightly to the left where Japanese troops still advanced despite the carnage all around them.

8 seconds after the first shot, the second followed.

Steel pellets swept through another section of the assault formation, adding dozens more bodies to the growing pile of dead.

First Lieutenant Okada felt the shock wave of the first canister round, pellets whistling just above his head.

One tore through the sleeve of his uniform, but left his skin unharmed.

He stared in disbelief as an entire rank of his company vanished in a mist of blood.

The precise formation he had spent weeks training dissolved into chaos in seconds.

Soldiers who had survived the first volley stumbled forward in shock, stepping over the mangled remains of their comrades, trying to keep the charge going toward the American line.

The third canister round struck a group of Japanese troops who had bunched together as they weave through fallen comrades.

An accidental cluster that proved fatal.

The force of the pellets lifted some men off their feet before slamming them back down to the ground.

McCulla fired with mechanical precision now, adjusting his aim between each shot to cover different sections of the assault formation.

Miller fed ammo steadily, the gun’s semi-automatic breach maintaining a relentless rate of fire that decimated the dense enemy ranks.

Other American positions along the ridge opened fire in turn.

A crossfire of rifles, machine guns, and mortars compounding the destruction wrought by the canister rounds.

Japanese soldiers who escaped the steel storm found themselves trapped in a rifle crossfire.

Any man who stood was cut down instantly.

What had been planned as an overwhelming assault to crush American defenses with numbers had devolved into a slaughter.

Enemy casualties mounted by the second and hope of advance for the survivors faded fast.

Lieutenant General Hiakutake watched the battle unfold from his command post two miles away.

The flash of gun muzzles lit up the jungle clearing and the sound of battle told him the assault was a catastrophic failure.

Radio contact with Okata’s regiment had been lost minutes after the attack began.

a sign that officers were either dead or too busy fighting for their lives to communicate with headquarters.

The sustained intensity of American fire revealed defensive preparations far more thorough than Japanese intelligence had suggested.

McCulla fired the seventh canister round at Japanese troops who had closed to just 70 yards of the American line.

At this close range, the pellets retained maximum velocity and density, wreaking absolute havoc.

The kinetic energy of a single pellet was enough to punch through a human body and hit multiple targets behind it.

Japanese troops caught in the fire were torn apart instantly, their bodies unrecognizable.

The Japanese assault began to falter.

Rearrank soldiers faced an ever growing wall of dead and wounded blocking their path.

Men who had charged forward with unshakable confidence in victory now faced American firepower unlike anything they had encountered in previous battles.

The spiritual strength that was supposed to overcome material inferiority crumbled in the face of a weapon designed specifically to destroy mass infantry.

First Lieutenant Okata fell to the mud 30 yards from the American line, mortally wounded, his sword still clenched in his right hand, his body riddled with steel pellets.

Remaining soldiers of his regiment crawled forward on all fours, some continuing to advance, even with mortal wounds that would kill them within minutes.

The bonsai charge that was meant to shatter American morale instead proved that raw human courage and numbers were useless against modern military technology.

Nearly 800 Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded in the clearing that had become a living hell.

Dawn broke and the full horror of the jungle clearing was revealed.

783 Japanese bodies lay scattered across the ground.

Their positions tracing a clear lethal arc of the canister rounds fire.

Marine burial details moved methodically across the battlefield, counting casualties, gathering intelligence, avoiding eye contact with the horrific damage the steel pellets had inflicted on human flesh.

Captain Hetinger walked among the bodies, studying the weapons effectiveness, taking notes for future battles.

The canister rounds had performed exactly as intended.

The interlocking killing zones they created left no infantry formation standing.

As morning sunlight filtered through the jungle canopy, Lieutenant General Haya Koutaki received casualty reports at his command post.

The numbers confirmed his worst fears of the assault’s failure.

Three entire companies had been all but annihilated.

Only 47 survivors of Okata’s regiment staggered back to Japanese lines.

The few wounded who could speak described a weapon they had never faced in China or the Philippines.

A cannon that fired a cloud of metal pellets, each shot capable of cutting down dozens of men.

The battle inflicted a psychological blow on surviving Japanese troops as deadly as the physical casualties.

After hearing tales of their comrades fate, entire platoon refused to obey orders to attack.

In the weeks that followed, American intelligence officers interrogated captured Japanese troops, documenting their reaction to canister fire and its impact on morale.

Sergeant Yamamoto, wounded by pellet shrapnel in his left shoulder and thigh, recounted the horrifying sight of his squad leader being hit by multiple pellets at once.

The prisoner explained that Japanese training had prepared soldiers to face rifle bullets and machine gun fire, but nothing had prepared them for a weapon that could kill dozens of men in a single shot across such a wide area.

Word of this new American weapon spread rapidly through Japanese forces across the Solomon Islands via survivors of subsequent battles.

3 weeks later, during the Battle of Edson’s Ridge, the same devastating scene played out again.

[clears throat] On September 13th, Company K, Third Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, attempted to assault American positions and walked into a storm of canister fire.

Three 37 millimeter guns opened fire in unison, inflicting 112 casualties in less than two minutes.

Japanese soldiers, who had faced enemy fire without flinching in previous battles, began to show signs of what American medics called combat fatigue, refusing to cross open ground where the deadly cannons might be lying in weight.

Captain Hetinger submitted a detailed afteraction report to Marine Corps headquarters documenting the tactical use of canister rounds and recommending revisions to standard infantry tactics.

His analysis showed that when properly positioned and supplied with ammo, a single 37mm gun firing canister rounds could hold off an assault-sized infantry attack.

When multiple guns fired in concert, their effectiveness multiplied exponentially, creating a seamless killing zone with no escape for the enemy.

The success on Guadal Canal prompted an immediate revision of US anti-tank gun doctrine across the Pacific.

A training manual published in October 1942 added a full chapter on canister round usage, complete with detailed diagrams marking optimal firing positions and engagement ranges for different tactical scenarios.

Artillery schools at Camp Lune and Quanico integrated anti-infantry training into their curricula, teaching gunners to calculate pellet dispersion patterns and select ammo types based on target characteristics.

Japanese commanders tried to adapt their tactics to counter the devastating power of canister rounds, but their options were limited by terrain and the very nature of their assault doctrine.

Hayakoutake attempted to send small units to infiltrate American lines at night, but the effort yielded little success against American defenses equipped with flares and search lights.

Attempts to suppress American artillery positions with mortars also failed as the highly mobile 37 mm guns could be quickly repositioned between shots.

The psychological warfare value of canister rounds grew even more pronounced in subsequent battles for Terawa and Saipan.

[clears throat] Japanese soldiers who had heard tales from Guadal Canal survivors grew increasingly reluctant to participate in bonsai charges.

American intelligence reports noted that beginning in early 1943, the frequency and intensity of Japanese human wave attacks declined significantly.

Enemy commanders increasingly turned to defensive tactics, avoiding exposing large numbers of troops to Americanmass firepower.

Sergeant McCulla wrote to his family in Michigan describing the weapons effectiveness, but military sensors deleted specific details about the ammo type and casualty numbers before allowing the letter to be sent.

His letter focused on the psychological impact of the battle, noting how Japanese soldiers, who had seemed superhuman in their fanatical courage, had suddenly shown their vulnerability in the face of a weapon they could not overcome with mere spirit.

The myth of Japanese invincibility and invulnerability in hand-to-hand combat had been shattered by American industrial might and tactical ingenuity.

Medics treating American wounded reported that after successfully repelling the bonsai charge, soldier morale soared and their confidence in surviving future battles grew significantly.

The psychological advantage of knowing American weapons could hold off the most determined enemy attacks far outweighed the immediate tactical gains.

In subsequent battles, fewer Japanese soldiers managed to close in on American positions, and US casualties from hand-to-hand combat dropped dramatically.

In 1943, production of canister rounds was ramped up significantly.

Commanders across the Pacific requested increased supplies for the upcoming amphibious assaults.

The Rock Island Arsenal expanded production capacity specifically to meet demand for 37mm canister rounds.

Quality control processes ensured every steel pellet met precise specifications for weight and diameter.

By December 1943, US forces in the Pacific had been issued more than 50,000 canister rounds distributed to anti-tank gun units from New Guinea to the Aleutian Islands.

Reinforcement training programs emphasized the importance of canister rounds in defensive combat.

New recruits spent extra time learning to load and fire this special ammo in simulated combat environments.

Artillery sergeants who had fought on Guadal Canal became instructors at artillery schools, passing on the invaluable lessons learned from three years of jungle warfare.

how to maximize the weapon’s devastating effectiveness through optimal engagement ranges and target selection.

The tactical revolution sparked by canister rounds extended far beyond immediate battlefield use.

It also influenced American weapons development for the remainder of the war.

Ordinance experts began designing similar anti-infantry ammo for other artillery systems, creating a family of weapons specifically tailored to counter Japanese human wave tactics.

The success of the 37 mm canister round proved that innovative ammo design could drastically improve the effectiveness of existing weapons without the need for entirely new manufacturing schemes or large-scale retraining of troops.

Japan’s military leadership gradually abandoned the bonsai charge as a core tactical doctrine, admitting that American firepower had evolved to a level traditional methods could not match.

The nature of warfare in the Pacific shifted rapidly with both sides adapting to the new reality.

But the first clash between Japanese courage and American steel pellets left a psychological mark that endured for the rest of the conflict.

March 1945, Hetinger returned to San Diego, the Silver Star Medal pinned to his uniform, awarded for his innovative use of anti-tank weapons against Japanese infantry on Guadal Canal.

The simple medal seemed an inadequate recognition for a tactical innovation that had fundamentally altered the course of the Pacific War.

But Hetinger never spoke publicly about his role in the development of modern tactics.

He accepted a teaching position at the Marine Corps Artillery School, spending the rest of his military career teaching a new generation of gunners the lessons of three years of jungle warfare.

The M3 37 mm anti-tank guns combat performance far exceeded its original design specifications.

It fought in every major Pacific campaign from Guadal Canal to Okinawa.

By the end of the war, a total of 4,800 units had been produced, and American arsenals had manufactured more than 2 million canister rounds.

The weapon’s versatility, performing both anti-tank and anti-infantry roles, made it an indispensable piece of equipment for marine and army units fighting in terrain where larger artillery could not be effectively deployed.

Sergeant McCulla survived four major amphibious assaults before returning to his hometown in Michigan in December 1945.

His service record chronicled his combat experience from Guadal Canal to Okinawa.

He never forgot the sound of steel pellets hitting human flesh.

A wet tearing sound that haunted his nightmares for decades after the war.

McCulla went on to work as a machinist in Detroit’s auto industry, applying the precision manufacturing skills he had learned in the military to peaceime production.

But he never spoke to his family about the true power of the weapon he had manned in the Pacific.

Post-war Japanese military historians acknowledged that the tactical surprise of American canister fire was a major factor in the failure of traditional assault tactics that had proven so effective in China and Southeast Asia.

Colonel Nouyoshi Masuda, a surviving Japanese officer who wrote extensively about Japan’s military defeats, cited the encounter with canister fire on Guadal Canal as the turning point that forced a fundamental revision of Japanese infantry doctrine.

The weapon had inflicted a psychological blow on Japanese soldiers as severe as the physical casualties.

Entire units lost their faith in their ability to overrun American defensive positions with mere spiritual resolve.

Private Miller completed his military service in April 1946, having participated in five amphibious assaults.

His 37 mm gun crew had used canister rounds to devastating effect against the enemy time and again.

His speed and reliability as a loader under fire earned him commenations from three artillery company commanders.

Though Miller considered his role modest compared to Marines fighting with rifles and bayonets, he used the GI Bill to attend college in Ohio and later became a high school math teacher.

He occasionally spoke of his military service, but never described the specific nature of his combat duties.

The tactical lessons of canister round usage shaped American military doctrine throughout the Cold War.

The US military developed similar anti-infantry ammo for larger caliber artillery.

75 mm towed howitzers were fitted with canister rounds holding 260 steel pellets and 105 mm howitzers with rounds packing 350 pellets.

All designed to shatter masked infantry formations.

These weapons proved effective in the Korean and Vietnam wars where US forces once again faced enemy tactics that emphasize close quarters human wave assaults.

Lieutenant General Harukichi Hayakutake was arrested for war crimes.

He died in Japanese custody in 1947 awaiting trial.

A series of tactical failures had cost the Imperial Japanese Army tens of thousands of lives, and his military career had ended in disgrace.

Memoirs discovered years later revealed he deeply regretted his decision to order a bonsai charge against American positions, citing intelligence failures that had failed to identify the new American weapons in the defense line.

Hayakutake criticized Japan’s military culture for its overemphasis on spiritual factors and disregard for material considerations, arguing that an objective assessment of enemy strength might have averted the disaster his troops faced.

The success story of the 37 mm gun did not end with the war.

Many of the weapons remained in US military inventories through the 1960s, used by the National Guard for training to teach a new generation of artillerymen the basics of direct fire.

These weapons, proven in combat, were transferred to Allied nations through military assistance programs, serving with distinction in the Korean War and various proxy wars during the Cold War.

Their mobility and reliability made them a valuable asset for Allied forces around the world.

Museums across the United States house examples of the M3 anti-tank gun and M2 canister rounds, but few visitors understand the weapon’s pivotal role in shifting the tactical balance of the Pacific War.

The National Museum of the Pacific War in Texas preserves an operational demonstration model capable of firing training rounds to show visitors how the canister system works, though safety regulations prohibit the use of live steel pellets.

Related educational materials describe the weapon’s dual role, but focus primarily on its anti-tank capability rather than its devastating effectiveness against infantry targets.

Manufacturing records preserved at the Rock Island Arsenal detail the precise craftsmanship required to produce effective canister rounds.

Quality control processes demanded pellet tolerances measured in thousands of an inch.

Production required specialized equipment and highly skilled workers.

a testament to the massive investment in American military manufacturing capacity and a reflection of its industrial superiority over Japan’s war production machine.

By 1944, American factories were producing canister rounds faster than combat units could consume them, building a strategic stockpile that ensured ample supplies for future operations.

The psychological impact of modern weapons extends far beyond immediate tactical results and it shaped Japanese strategic planning for the remainder of the Pacific War.

Intelligence reports captured after Japan’s surrender revealed that military leadership had extensively debated how to counter American anti-infantry artillery, proposing solutions ranging from dispersed assault tactics to developing protective gear for infantry units.

But none of these counter measures came to fruition, hampered by declining industrial capacity and the everinccreasing sophistication of American defensive systems.

Captain Hetlinger’s innovation is a microcosm of American tactical adaptability during the Pacific War.

Frontline troops modifying existing weapons and procedures to meet the unique demands of combat.

Similar innovations could be seen across the battlefield.

Napal developed for jungle warfare, flamethrowers used to attack fortified positions, and more.

American commanders willingness to experiment with new technology and abandon traditional doctrine when the situation demanded it gave them a decisive advantage over an enemy bound by a rigid tactical system.

Private Miller completed his military service in April 1946.

Having participated in five amphibious assaults, his 37 mm gun crew had used canister rounds to devastating effect against the enemy time and again.

His speed and reliability as a loader under fire earned him commendations from three artillery company commanders.

Though Miller considered his role modest compared to Marines fighting with rifles and bayonets, he used the GI Bill to attend college in Ohio and later became a high school math teacher.

He occasionally spoke of his military service, but never described the specific nature of his combat duties.

The tactical lessons of canister round usage shaped American military doctrine throughout the Cold War.

The US military developed similar anti-infantry ammo for larger caliber artillery.

75 mm towed howitzers were fitted with canister rounds holding 260 steel pellets and 105 mm howitzers with rounds packing 350 pellets.

All designed to shatter massed infantry formations.

These weapons proved effective in the Korean and Vietnam wars where US forces once again faced enemy tactics that emphasize close quarters human wave assaults.

Lieutenant General Harukichi Hayakutake was arrested for war crimes.

He died in Japanese custody in 1947 awaiting [clears throat] trial.

A series of tactical failures had cost the Imperial Japanese Army tens of thousands of lives, and his military career had ended in disgrace.

Memoirs discovered years later revealed he deeply regretted his decision to order a bonsai charge against American positions, citing intelligence failures that had failed to identify the new American weapons in the defense line.

Hayakutake criticized Japan’s military culture for its overemphasis on spiritual factors and disregard for material considerations, arguing that an objective assessment of enemy strength might have averted the disaster his troops faced.

The success story of the 37 mm gun did not end with the war.

Many of the weapons remained in US military inventories through the 1960s, used by the National Guard for training to teach a new generation of artillerymen the basics of direct fire.

These weapons proven in combat were transferred to Allied nations through military assistance programs serving with distinction in the Korean War and various proxy wars during the Cold War.

Their mobility and reliability made them a valuable asset for Allied forces around the world.

Museums across the United States house examples of the M3 anti-tank gun and M2 canister rounds, but few visitors understand the weapon’s pivotal role in shifting the tactical balance of the Pacific War.

The National Museum of the Pacific War in Texas preserves an operational demonstration model capable of firing training rounds to show visitors how the canister system works, though safety regulations prohibit the use of live steel pellets.

Related educational materials describe the weapon’s dual role, but focus primarily on its anti-tank capability rather than its devastating effectiveness against infantry targets.

Manufacturing records preserved at the Rock Island Arsenal detail the precise craftsmanship required to produce effective canister rounds.

Quality control processes demanded pellet tolerances measured in thousands of an inch.

Production required specialized equipment and highly skilled workers.

a testament to the massive investment in American military manufacturing capacity and a reflection of its industrial superiority over Japan’s war production machine.

By 1944, American factories were producing canister rounds faster than combat units could consume them, building a strategic stockpile that ensured ample supplies for future operations.

The psychological impact of modern weapons extends far beyond immediate tactical results and it shaped Japanese strategic planning for the remainder of the Pacific War.

Intelligence reports captured after Japan’s surrender revealed that military leadership had extensively debated how to counter American anti-infantry artillery, proposing solutions ranging from dispersed assault tactics to developing protective gear for infantry units.

But none of these counter measures came to fruition, hampered by declining industrial capacity and the everinccreasing sophistication of American defensive systems.

Captain Hetinger’s innovation is a microcosm of American tactical adaptability during the Pacific War.

Frontline troops modifying existing weapons and procedures to meet the unique demands of combat.

Similar innovations could be seen across the battlefield.

Napal developed for jungle warfare, flamethrowers used to attack fortified positions, and more.

American commander willingness to experiment with new technology and abandon traditional doctrine when the situation demanded it gave them a decisive advantage over an enemy bound by a rigid tactical system.

News

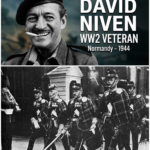

David Niven – From WW2 to Hollywood: The True Story

VIn the annals of British cinema, few names conjure the image of Debonire elegance quite like David Nan. The pencil…

Japanese Pilots Couldn’t believe a P-38 Shot Down Yamamoto’s Plane From 400 Miles..Until They Saw It

April 18th, 1943, 435 miles from Henderson Field, Guadal Canal, Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto, architect of Pearl Harbor, commander of the…

His B-25 Caught FIRE Before the Target — He Didn’t Pull Up

August 18th, 1943, 200 ft above the Bismar Sea, a B-25 Mitchell streams fire from its left engine, Nel fuel…

The Watchmaker Who Sabotaged Thousands of German Bomb Detonators Without Being Noticed

In a cramped factory somewhere in Nazi occupied Europe between 1942 and 1945, over 2,000 bombs left the production line…

The Priest Who Recorded SS Confessions in the Booth and Sent Them to the Allies

Munich, 1943. The confessional booth of St. Mary’s Church stood in the shadows of the nave, a wooden sanctuary…

FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis Charity — $250M Terror Network & Governor ARRESTED

At 11:47 on a bitter Tuesday morning, federal agents stepped in front of the cameras in Minneapolis and delivered a…

End of content

No more pages to load