Thomas had learned to live as a shadow.

At nineteen, he could move from dawn to dusk without drawing a single eye: back bent in the rows, head down when the overseer rode past, face unreadable in the presence of the master.

On the Caldwell plantation they called him Ghost, not in mockery but in respect for survival; a man who did not exist could not be whipped for being himself.

That morning the overseer’s voice split the fields like a lash.

“Boy! Master wants you at the house.

Now.”

Thomas straightened, breath catching, the sudden vertigo of being seen after years of careful invisibility.

He searched the last days for any misstep—an extra ladle of water, a word said too loud—but nothing rose.

He wiped his palms on his trousers and walked up the path that cut through trimmed hedges like a scar.

Matilda met him at the servants’ entrance with a grip that bit into his forearm.

“Listen,” she hissed, eyes flicking to the hallway.

“Master’s gone to town.

The mistress wants you to clean their bedroom.” Her voice dropped.

“Don’t talk unless she speaks.

Don’t look her in the eye.

Don’t touch nothing but a broom.”

Under the fan-light, the big staircase curled upward with the grandeur of a threat.

Field slaves did not climb those steps.

Field slaves did not push open the door to the master’s bedroom.

But Thomas did, because a man in his place did what he was told and prayed to remain no more than hands and feet.

He knocked softly.

When no one answered, he knocked again, knuckles skittering across oak polished to a mirror.

“Enter,” came a woman’s voice—calm, not kind, but not sharp either.

He stepped into a room that smelled of lavender and beeswax.

Light fell through lace curtains, catching dust like tiny constellations.

Silk on the bed.

Porcelain shepherdesses smiling on a mantel.

A world he had only ever seen through a doorway.

“You must be Thomas.”

His head snapped up before he could stop it.

She sat by the window with a book open in her lap.

Eleanor Caldwell was younger than he’d expected—early twenties, maybe, with chestnut hair pinned loosely, honey-brown eyes that watched him with a frankness that felt like a hand on his chest.

The simple blue of her dress barely disguised its fine weave.

He dropped his gaze to the Persian rug so he wouldn’t drown in the wrong kind of eye contact.

“Look at me, please,” she said.

Matilda’s warning flared like a wound.

Men had died for less than that glance.

The memory of Jacob’s bare feet swinging three summers ago snapped him rigid.

“I said, look at me.” Her tone didn’t sharpen; it steadied, and there was something in it—an absence rather than a presence, not cruelty, not the savor of making a man small.

Slowly, Thomas lifted his eyes.

“Do you know why I asked for you?” Her head tilted, a wisp of hair falling free.

He shook his head.

“I’ve watched you in the fields,” she said.

“You see.

You think.” She stood and came closer than propriety allowed.

For the first time he noticed she smelled faintly of rose water rather than strong perfume.

“And I believe you can read.”

The word fell like iron.

Reading was forbidden; the accusation alone could mean the post—raw back, salt, flies.

He opened his mouth to protest and felt his tongue stick to dryness.

“Don’t lie,” she said softly.

“Last month when that newspaper blew into the yard? You followed the lines with your eyes.

Your lips moved.”

He nearly staggered.

Had he been that careless? Or had she simply been looking when no one else did?

“My husband thinks I pass my days with needlepoint and nonsense,” she went on, as if listing facts.

“He thinks a woman’s mind is a porcelain teacup—delicate, ornamental, useful only for show.” A half-smile flashed and died.

“No one suspects that a field hand might teach himself letters by moonlight.”

She went to a pastoral painting above the low bookcase and swung it on hidden hinges.

Behind velvet lining lay a small cache: three books, some folded papers, a bundle of letters tied with string.

“My husband would beat me if he knew about this,” she said without melodrama.

“Philosophy, politics, science—things ‘not for ladies.’” She looked back at him.

“We each have our forbidden knowledge.”

Thomas stood rooted.

The mistress had unfolded a secret life at his feet as if she were laying out table linen.

Alarm pounded through him.

Men died for knowing things they weren’t supposed to know.

And yet a sharp spark rose with the fear—recognition, maybe, the sudden sensation of a locked door in his mind lifting on oiled hinges.

“I need someone I can trust,” she said.

“Someone intelligent.

Someone who understands the cost of secrets.” Her eyes searched his face.

“Someone with everything to lose, as I do.”

“Why me?” he asked.

The question escaped before caution could kill it.

“Because you looked at a newspaper like a thirsty man looks at water,” she said, and for the first time her smile reached her eyes.

“Because you watch when others think no one is watching.

Because I think you want more than this life allows.” She paused.

“As do I.”

Her life, he realized, wasn’t the cloth-of-gold picture the Sundays made it.

He’d heard the kitchen tales—how she never quite fit with the planters’ wives, how she kept fewer lace gowns than was proper.

A gilded cage shrank the same as a wooden one.

Perhaps she had learned to pace.

“What is it you want?” he asked.

“To take away the only thing my husband values,” she said.

She set the book down.

“His reputation.” She crossed to the mirror and watched her own reflection as she spoke.

“He kept a house for a woman in Charleston.

A free woman of color.

He gave her my grandmother’s jewelry.

He thinks I’m too stupid to know.” Her knuckles whitened on a silver brush.

“He also thinks I’m too stupid to find his ledgers.”

She turned from the mirror.

“He has papers in his study—letters, accounts.

Evidence that he’s been siphoning money out of my inheritance for years.

Correspondence with men you’ve never heard of and men you have—names polite society refuses to say out loud.” She took a breath.

“I need copies.

Exact copies.”

The air in the room thinned.

He accepted what she was asking even before she finished.

If he helped her and they were caught, there would be no quick swing and merciful break.

Caldwell had a talent for slow lessons.

“What’s in it for me?” he heard himself say, and in that moment he knew his life had already broken off along a line only he could see.

Instead of summoning rage, she startled him with a different honesty.

“Freedom,” she said.

“I’m leaving when this is done.

Boston.

My father’s family.

I can arrange papers for you—free papers that would pass.

Money to get you north.” She held his gaze.

“And I can tell you where your sister went.”

The name came like a blow to his chest.

“Lily?” They had sold her when she was eleven.

Caldwell had lied a dozen lies: a family in Virginia, a gentler house.

Thomas had never believed a single word because none had ever believed him.

“How do you—”

“I know many things people think I don’t,” she said.

“I know your mother taught you letters before she died.

I know you read when shadows say you aren’t.

And I know you’ve never stopped looking down roads that won’t look back.”

He didn’t remember moving, but he found himself close enough to see the freckles she tried to powder.

He had a choice: clutch at the broom handle of safety or reach for a key he might never get to turn.

“When?” he asked.

She exhaled as if she’d been holding her breath since he’d walked in.

“Tomorrow.” She slid a small brass key from a hidden drawer and placed it in his palm.

It was warm against his skin.

“We’ll say you’re recalking windows in the west wing.

The study is at the far end.

There’s a hidden compartment behind a shelf.” Her hand brushed his.

A small bright spark leapt and was smothered—not by disgust, not by desire, but by the weight of what that touch could cost.

“This will get us both killed,” she said.

“If we fail.”

He glanced at the painting, at the book, at the silver on the vanity.

“I’ve been dying a day at a time for nineteen years,” he said.

“If I’m going to get killed, it might as well be for something that means something.”

“Trust no one,” she said at the door.

“Not even friends.

Betrayal keeps these places standing.” Her voice dropped.

“There’s a free black man in town.

Solomon Pike.

Runs the cooperage.

If I can’t help you, find him.

Tell him ‘the mockingbird still sings.’”

She left him with a broom and a key and a heart like a locked room.

He swept a floor that did not require sweeping, thinking of a girl with a serious mouth and eyes older than they should have been.

Morning came with a mist that bent the fields against the light.

Thomas woke in the gray, stepped over the sleeping limbs of the men who shared his space, cooled his face at the well.

“Windows today?” Samuel asked from the shadows by the stable.

The old man’s eyes were clouded and sharp both.

“Just windows,” Thomas said.

“Mm.” Samuel’s mouth folded.

“Windows let you see out.

They let others see in.”

By midmorning Thomas stood in Caldwell’s study with a toolbox in his hand and Matilda’s scowl planted on her face for any watching eyes.

Eleanor flicked her glance up only when the door shut.

“We don’t have much time,” she said.

The bookcase swung.

The safe gave with the code she’d memorized from three years of polite boredom.

Inside: a ledger so neat it could cut a finger, letters tied with string, a few small boxes that sounded like teeth when she set them down.

She led him to a panel in the wainscoting.

“There’s a small room,” she whispered.

“It was used to hide people before the war.” The panel breathed open.

Inside, a narrow desk, an oil lamp, quills, a cot barely wider than a body.

“Work here,” she said.

“Three knocks if danger.”

For two hours he copied numbers with the care of a man writing his own name for the first time.

Caldwell’s precise hand laid out the theft clean—figures diverted from Eleanor’s trust to shell accounts, to parcels in Charleston, to payments described only by initials.

He was halfway through the ledger when three sharp taps rattled his ribs.

He capped the ink, smothered the flame, held still so hard his heartbeat seemed an offense.

Through the panel he heard Eleanor’s light voice and the master’s heavier one.

“Just checking for water,” she said with a hint of annoyance.

“I’ve told you not to enter without asking.” Caldwell’s tone hardened.

“Where is the slave from the windows?” “In the library,” she answered smoothly.

“The storm.”

When the danger passed, she slid the panel back, expression tight.

“He’s suspicious,” she said simply.

“Finish what you can.”

Near the end of the ledger Thomas found entries marked S.P.

— regular, small payments.

“Solomon Pike,” she said when he asked.

“He owes my husband for something my husband holds over him.” She didn’t elaborate.

He wanted to ask, and didn’t.

In the house, questions were a luxury.

They didn’t get everything that day.

Caldwell came back early from town in a temper and announced a delay in his trip to Charleston.

Matilda’s warning that “the walls have ears” felt like an extra weight in Thomas’s pocket.

At midnight, when the house glowed with a single lamp in the west wing, he came anyway.

They finished the ledger.

They started the letters the next day once the carriage wheels rattled away and the overseer grumbled up a false work assignment.

The correspondence painted a web darker than money—men who refused the end of a war, militiamen named politely as “associations,” dates and sums and places to exchange shipments for loyalty.

General William Barton’s signature came up like a weed.

“He wants a second uprising,” Eleanor said.

“My husband lacks courage, so he uses paper.”

The butler had eyes and a mouth and a loyalty to Caldwell.

Matilda passed word.

“He’s asking why the mistress sends for you,” she said, her scowl not reaching the worry in her eyes.

“Be careful.” Thomas and Eleanor closed up the safe and smiled at people who deserved nothing but the truth.

“Tonight,” she whispered after one such interruption.

“Midnight again.”

They worked until candles guttered and hands cramped.

Inside the hidden room, the lamp’s halo made their faces a strange kind of honest.

“There’s something else you should know,” she said finally, turning the quill in her fingers heedless of the ink.

“I have a daughter.

She’s in Massachusetts with my sister.

He says I’m too nervous to be a proper mother.”

Thomas saw the flash of an oval locket when she spoke.

He had not known this about her; it clattered into place with the other parts of the woman he’d met by a window with a book.

“Everything I do is to get to her,” she said.

“And to make sure she never wears the stain of his life.”

“And you?” he asked, surprising himself again.

“Where does your allegiance lie?”

“With justice,” she said, and for once it didn’t sound like a word she’d read.

“And with her.”

They made a plan so fine it would have been art if it had not been survival.

Thomas would work legitimate hours in the west wing.

He would copy when he could be unseen.

Eleanor would create reasons and alibis and mishaps with curtains that suddenly needed hemming.

Matilda would run interference across a dozen rooms.

At the end of three days, a man would come at dusk to take the papers north.

They would both breathe.

What Thomas didn’t know, couldn’t know, was that the butler had not merely watched but acted; a rider was already two towns away with a letter in his pocket that would call Caldwell back from Charleston before he reached the bridge.

He didn’t know that the watcher in the stable shadows had seen him slip through the west door and measured how often the lamp in the study burned late.

He didn’t know that Samuel had watched a hundred such dramas from a corner and could hear how the ground would give.

“Whatever you’re doing,” the old man said one evening under an oak, “remember: white folks’ quarrels land on black backs.” He pressed his hand once to Thomas’s arm.

“Your daddy had the same fire.

It’s a light in a dark place.

It’s also a torch that draws attention.”

On the last day, as the sun slid and the kitchen clangor rose, Eleanor and Thomas tucked the last copied letter beneath the loose board in her sitting room, the ledger’s double hidden behind a river painting that had never seen the sea.

“He leaves at noon,” she said.

“My contact comes at dusk.” She fixed his collar like a mother might.

“Tonight,” she added.

“I’ll end what needs ending.”

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“He beats me when I cross him,” she said as if reporting weather.

“He will beat me for selling him out even if he never proves a thing.

The law will not protect me.

There is no law for women like me besides men’s moods and books their friends sign.” Her hands were steady.

“I intend to deprive him of both.”

At dusk the carriage returned—not empty but heavy with Caldwell’s fury.

The butler had written; Caldwell had read.

He stormed into the house smelling of sweat and distance.

He stopped in the study doorway, jaw tight.

“Where is he?” he demanded.

“The field hand you fancy enough to call to my desk whenever you please?”

Eleanor turned from her writing with the smoothness she wore for Sunday.

“If you mean the boy fixing the windows,” she said, “he’s in the library.

There’s a draft.” Her tone drew his eye away from the bookcase.

He sniffed, suspicious and vain in equal measure, and let her guide him to a new annoyance.

“You can still leave,” Thomas said later, in the hidden room where her face was wet in the lamplight and his hands shook from trying too hard not to shake.

“Go while he sleeps.

Now.”

“He doesn’t sleep when he’s angry,” she said.

“And he found the keyhole.

He’s counting my breaths.

He won’t go to bed until he’s made sure he owns the air in this house again.” She looked at him.

“You go.”

“I have copies,” he said.

“But if he kills you, no one will see them.” He swallowed.

“And he will kill you for making him a fool.”

She looked away.

“Then don’t let him.”

Midnight struck.

The house throbbed with its own quiet.

Eleanor slipped from the bedroom and met Thomas by the study door in bare feet.

“He’s drunk,” she whispered.

“He fell asleep.

He never falls asleep.” Relief loosened Thomas’s shoulders a fraction.

They moved into the study.

Eleanor opened the safe without a sound and handed him the bundle.

“Take these to the cooperage,” she said.

“Now.

Give them to Solomon Pike.

Tell him the phrase.” She closed the safe and spun the dial.

When she turned, he was still there.

“Go,” she said.

“Every breath we take is borrowed.”

He left by the west door and ran the path Samuel had taught him would hold his steps in the dark.

The cooperage smelled of wood and sap even at night.

A figure stepped from the shadow.

“You must be Thomas,” Solomon Pike said, voice low, steady, eyes taking in nothing and everything in equal measure.

“The mockingbird still sings?” Thomas said.

“Always does when the hunter isn’t listening,” Pike answered.

He took the papers.

He didn’t ask questions.

“Go back,” he said.

“Walk like you belong.

Walk like you been in this place your whole life.

The dance is not over.”

Thomas stepped into the yard with breath he did not know he’d held.

The sky was brittle with stars.

He could have kept walking, could have melted into the treeline, could have thrown himself on the river’s mercy.

He turned back toward the house because he was not a ghost; he was a man with a debt to pay and a promise to keep.

He was halfway up the hill when the shot cracked from the study.

The sound split the night and stitched it up again.

He ran because he did not think.

He reached the window and saw inside—Caldwell on the floor, eyes wide in the ruling he could no longer file, blood spreading into the grain of wood like spilled ink.

Eleanor standing with both hands on the pistol, jaw clenched, knuckles white, hair down around her face like a halo broken and crooked.

Her eyes met Thomas’s through the glass for one long pulse.

He saw in them not triumph, not even relief—only a steadiness so hard it looked like mercy.

“Go,” she mouthed.

He shook his head.

She moved to the desk and took nothing.

She left the pistol where it lay.

She opened the door into the corridor, straightened her nightgown, and screamed.

The house jerked to life.

By dawn, the judge from town would come.

The pastor would stand in a dark suit in the doorway and try not to look at the rug.

The sheriff would listen to Matilda’s statement and write it down neat—the mistress had awoken to a noise and found her husband shot by an intruder or a slave—she did not know which.

The butler would blink a little too slowly.

Samuel would watch from the yard with his hat in his hands and think about fires.

By dusk, Solomon Pike would slide a packet into a false bottom of a barrel heading north, and a man with a badge in a different city would open it and frown and begin to move his own pieces on his own board.

In three days’ time, Eleanor Caldwell would leave the Caldwell house—escorted, to the letter of the law, by two men who would make sure a young widow got where she said she was going—and in the shadow of that careful trip other shadows would separate and then join.

By nightfall Thomas would step onto a dirt road he had walked a thousand times without seeing.

He would carry nothing but what his mother had put in his head and what a woman had put in his pocket.

When he reached the trees beyond the field and the river beyond the trees, he would stop and look back.

The great house would stand white against the dark, one lamp burning, a stubborn rectangle of light that would fuel a thousand stories no one could prove.

He would think of the question Samuel had put to him without asking.

What would you choose if you could choose? Safety or something else?

He would step into the trees because he had already chosen.

Not safety.

Not quite freedom yet.

Something more precious than either, because it was both and neither: the knowledge that his life could tilt on a word—look—and that he could tilt it himself with another—yes.

On the Caldwell plantation they would tell a dozen different versions of what happened in the weeks that followed.

Some would make the mistress a serpent.

Some would make her a saint.

Some would make Thomas a villain, some a ghost.

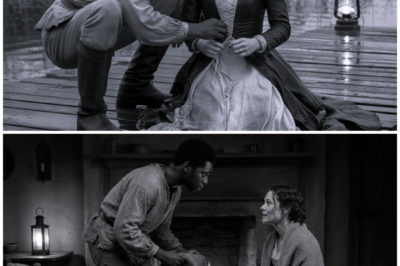

None of those stories would be more true than the simplest one: a young man was sent to clean a room he had no right to enter and found a woman waiting alone.

Their eyes met.

In that meeting, the shape of two lives and the shape of a place changed forever.

Years later, if you asked Thomas what he remembered of that first day, he’d say the smell of lavender, the cool of polished wood under his fingertips, the way the light made dust look like a galaxy that had always existed but needed the right angle to be seen.

And he’d say the way a single key pressed against his palm felt like everything he had ever been promised and everything he had never dared want at once.

News

A Slave Boy Sees the Master’s Wife Crying in the Kitchen — She Reveals a Secret No One Knew

Samuel learned to live without sound. At twelve, he could pass from pantry to parlor like a draft—present enough to…

(1855, AL) The Judge’s Widow Ordered Two Slaves to Serve Her at Night—One Became Her Secret Master

The townspeople of Fair Hope said the Ashdown house never quite went dark after the judge died. On still nights…

Slave Man Carried Master’s Wife After She Fainted — What She Did in Return Shocked Him

The sun hammered the Georgia cotton fields until the air itself felt heavy. Solomon worked on, hands moving through the…

Slave Man Helped Master’s Wife Undress After She Fell in the Lake — Then This Happened

On a summer afternoon when the heat pressed down hard enough to quiet even the birds, a woman slipped at…

A Slave Man Protected Master’s Wife From Bandits — What She Did Next Left Him Speechless

Solomon kept his eyes pinned to the dusty road as he guided the team, careful not to glance at Mrs….

The Plantation Mistress Who Chose Her Strongest Slave to Replace Her Infertile Husband

They found the master’s body at dawn, face down in the lily pond, his pockets full of stones. What troubled…

End of content

No more pages to load