This picture looks sweet, but there’s one object that reveals this slave child’s dark secret.

Dr.Rebecca Morgan carefully removed the protective sleeve from the newly acquired photograph in the special collections department of Emory University.

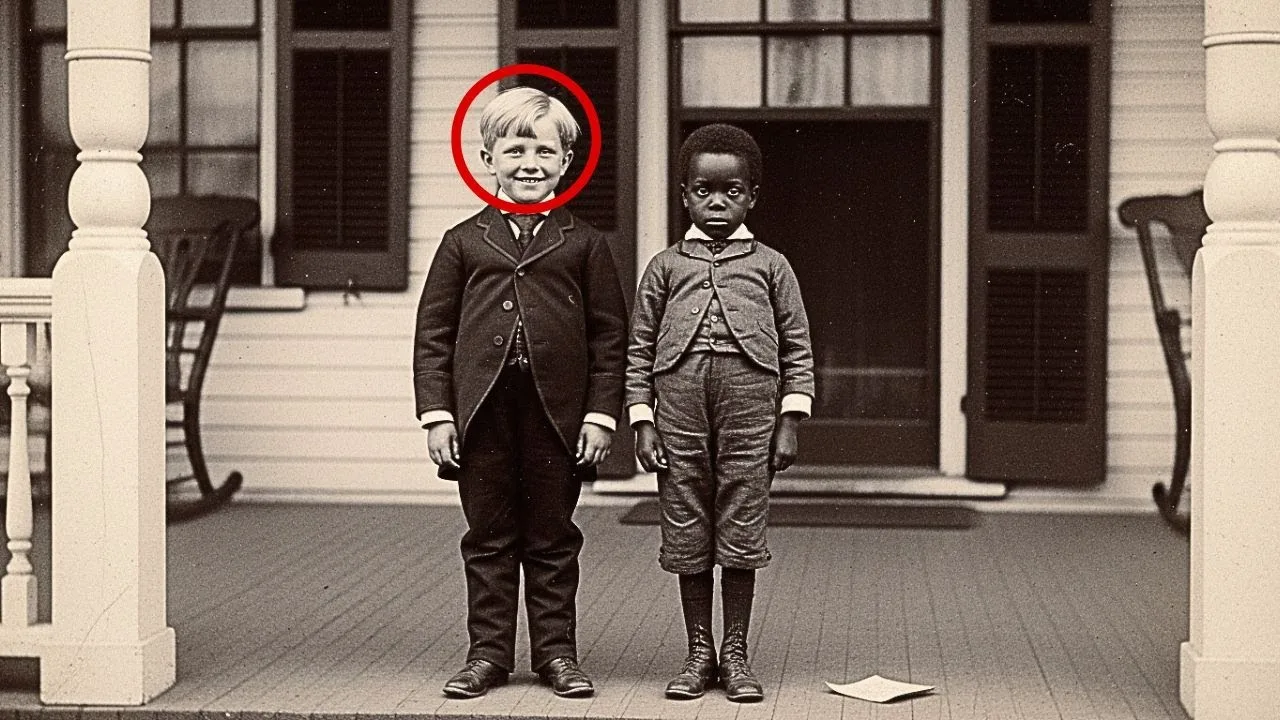

The sepia toned image from 1857 showed two boys standing side by side on the porch of a grand southern home.

One boy, fair-haired and smiling in an expensive suit, appeared to be around 8 years old.

Beside him stood another boy of similar age, a black child in formal attire that was slightly too large for his thin frame.

Another stage plantation photograph, Rebecca murmured, familiar with how slave holders often documented their human property alongside family members.

She was about to return it to the archive when something in the lower right corner caught her eye.

Partially visible at the edge of the frame, almost as if it had been accidentally included, lay what appeared to be a piece of paper on the ground near the black child’s feet.

Rebecca reached for her magnifying glass, her heart quickening as the details came into focus.

My god, she whispered.

It was a slave auction notice, the corner showing a date, April 15th, 1857, and partial text.

Healthy negro boy, Elijah, age 8, suitable for house or field.

She checked the photograph’s date stamp, April 13th, 1857, 2 days before the auction.

Rebecca’s hands trembled slightly as she turned the photograph over.

On the back, elegant handwriting read, “William with house boy, spring 1857.” Below, a different handwriting, smaller and less practiced.

Remember Elijah? The black child in the photograph had a name, and someone had wanted it preserved.

His eyes, looking directly at the camera, held none of the forced cheerfulness of typical plantation photographs, and they were steady, resigned, and heartbreakingly aware.

Rebecca knew immediately this wasn’t just another historical artifact.

It was evidence of a moment frozen in time.

The last documented day of a child’s life before being torn from everything familiar.

We need to find out what happened to Elijah, she said to her assistant.

Someone wanted us to remember him.

Now we will.

Rebecca spread her research materials across the table.

Plantation records, auction documents, and newspapers from 1857 Georgia.

The photograph of the two boys sat before her.

Elijah’s eyes seeming to watch her work.

The plantation was Magnolia Creek, owned by the Harrison family, her assistant, Daniel, said, placing a ledger beside the photo.

Financial records show they were struggling after the cotton blight of 1856.

Selling slaves to cover debts.

Rebecca nodded grimly.

A common practice.

A newspaper advertisement confirmed the auction.

Estate sale at Wilks County Courthouse.

Negroes, livestock, and furnishings of Magnolia Creek Plantation.

April 15th, 1857.

Further down the list of items for sale.

Boy Elijah, age eight, housrained reads simple words.

600 Rebecca Paul.

He could read.

That was unusual and illegal in most southern states.

D.

She examined the photograph again, noting the careful positioning.

The white child, William Harrison, centered and elevated slightly above Elijah.

But something about the composition seemed off.

The auction notice shouldn’t be visible, she said.

These photographs were carefully staged.

Daniel nodded.

It’s as if someone deliberately arranged for it to be in the frame.

Their research led them to the photographer Frederick Simmons, one of the few traveling photographers working in rural Georgia in the 1850s.

His client list included wealthy plantation owners wanting family portraits.

Most intriguing was a letter in Simmons sparse records addressed to an abolitionist newspaper in Boston.

I send these images not for publication, as it would endanger many, but as evidence of what words alone cannot convey.

He was documenting slavery while pretending to serve the plantation owners, and Rebecca realized.

In an inventory of items sold at the auction, they found the entry.

Negro boy Elijah sold to James Fletcher of Charleston for $675.

“We have a name and a destination,” Rebecca said, her determination growing.

“Now we need to find what became of him after he left Magnolia Creek.” The trail was thin but present, leading them toward Charleston and the next chapter in Elijah’s life.

Rebecca traveled to the Charleston Historical Society, where a collection of Frederick Simmons papers had recently been donated by his great-granddaughter.

The aging leather portfolio contained correspondents, receipts, and most valuably, his private journal.

April 13th, 1857.

Rebecca read aloud.

Completed portraits at Magnolia Creek.

Harrison boy typically demanding.

The other child, Elijah, remained still as stone throughout.

He knows what comes.

The auction notice fell from Harrison’s pocket during the sitting.

I repositioned it slightly rather than removing it.

Small acts of truth are all I can manage in these circumstances.

Further entries revealed Simmons’s growing moral conflict, earning his living photographing the very society he had come to despise.

May second, 1857.

Another entry read, “Received word that my Magnolia Creek photograph has reached Boston safely.

Contact there believes it may be useful to the cause, though I fear too late for the child.” Most significantly, Rebecca discovered Simmons had maintained a record of where his subjects ended up when possible.

Next to Elijah, Magnolia Creek, he had written, “Sold to Fletcher, Charleston.

Reported literate dangerous knowledge.

Fletcher owned a shipping business.” Daniel reported from his research.

He purchased several young slaves that year for his household and as dock workers.

Rebecca’s investigation led her to Fletcher’s business records, which included an inventory of household staff.

Elijah appeared on the list as house boy assigned to Mrs.

Fletcher.

Mrs.

Emily Fletcher was involved with a women’s reading society, Rebecca noted, reviewing the society’s sparse records.

Several members were quietly northern sympathetic, though not openly abolitionist.

A household ledger contained a surprising entry from Mrs.

Fletcher.

New boy showing aptitude with letters.

We’ll continue instruction discreetly.

She was continuing his education, Rebecca said, surprised.

That was extremely unusual and risky.

Most revealing was a letter from Emily Fletcher to her sister in Philadelphia.

The child came to us already knowing his letters.

Someone had clearly taught him, despite the laws against it.

To extinguish such a light would be a greater sin than nurturing it in secret.

The pieces were connecting, forming a more complex picture than Rebecca had initially imagined.

A photographer documenting brutal truths, a child with forbidden knowledge, and a mistress making a dangerous choice.

Elijah went from one unusual situation to another, she told Daniel.

But what happened to him as the winds of war began to blow? Rebecca walked the narrow streets of Charleston’s historic district, stopping before the three-story townhouse that once belonged to the Fletcher family.

Now an upscale restaurant, nothing marked its history as a place where a young enslaved boy with dangerous literacy once lived.

Fletcher’s household records from 1858-1 1861 showed Elijah’s position evolving from house boy to personal servant to the Fletcher’s son George who was 2 years older.

This pairing of enslaved and owner’s children was common, Rebecca explained to her department head via video call.

The enslaved child would serve as companion and servant, often sleeping on a pallet in the child’s room.

Most intriguing were entries in young George Fletcher’s school primers discovered in a family collection.

Alongside George’s practiced handwriting were other practice sheets, less refined, but showing remarkable progress.

Someone else had been using the same books.

Emily Fletcher was teaching them both, Rebecca theorized, using her son’s education as cover for teaching Elijah.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 disrupted Charleston life dramatically.

James Fletcher’s shipping business records showed mounting financial troubles as union blockades tightened around southern ports.

A ledger entry from October 1861 recorded, “Household reductions necessitated by war conditions.

Staff reduced by half.

Boy Elijah retained at Mrs.

Fletcher’s insistence despite financial advisability of sale.

She protected him,” Daniel noted.

More revealing was a diary entry from a neighbor’s daughter, describing a Christmas gathering.

“Mrs.

Fletcher’s house boy surprised everyone by playing a complex boach piece on the pianoforte.

Mr.

Fletcher seemed displeased by the display, though others were impressed.

The boy was promptly sent from the room.

His education was expanding beyond basic literacy, Rebecca said, which would have been increasingly dangerous as he grew older.

The most significant discovery came from a Confederate military dispatch dated June 1862.

Suspected underground railroad activity near Fletcher residents, household to be monitored for Northern sympathies.

Shortly after, a police report noted, “Negro boy approximately 13 years missing from Fletcher household.

Suspected runaway possibly harbored by unionist sympathizers.” Elijah escaped,” Rebecca whispered, feeling a connection to the boy whose eyes had first drawn her into this investigation.

“But how and where did he go?” In Philadelphia’s historical society, Rebecca searched records of underground railroad activities.

The network’s secretive nature made documentation sparse, but certain patterns emerged.

A Quaker journal from August 1862, mentioned receiving a young scholar from Charleston, aged approximately 13, showing remarkable aptitude despite limited formal instruction.

Rebecca told Daniel over their research call.

That fits Elijah’s description and timing.

Daniel agreed.

The journal belonged to Hannah Wells, a Quaker educator who operated a small school for freed and escaped enslaved people.

Her coded records noted a new arrival e brought north via the coastline, a reference to the maritime escape route that used sympathetic ship captains to transport escapees.

Emily Fletcher had connections to Philadelphia through her sister.

Rebecca noted she may have arranged his escape as Charleston became more dangerous.

School records from Wells Academy listed a student identified only as E, whose progress was noted as extraordinary, particularly in mathematics and music.

A margin note added, “History of trauma evident.

Nightmares continue.” Most revealing was a letter from Wells to a colleague.

Our young scholar from Charleston carries a photograph he keeps hidden from all but me.

It shows him in his previous life standing beside the son of his former owner.

He says it reminds him daily of what awaits others still in bondage.

He kept the photograph, Rebecca said, her voice catching.

The very one we’re researching.

By 1863, records showed E assisting with teaching younger students while continuing his own education.

As the war intensified, Wells’s journal noted, “E expresses desire to contribute to the Union cause.” His knowledge of Charleston’s geography and shipping could prove valuable, though I fear for his safety.

The Union Intelligence Report from October 1863 mentioned, “Young negro informant, formerly of Charleston, providing detailed information on Confederate shipping patterns and coastal fortifications.

Intelligence deemed highly reliable.” “He became a spy,” Daniel said, amazed.

“At 14,” Rebecca nodded.

“Many formerly enslaved people did, using their intimate knowledge of southern geography and customs to help Union forces, but most of their contributions went undocumented or deliberately obscured for their protection.

As the war progressed toward its bloody conclusion, Elijah’s trail led into increasingly dangerous territory and toward a momentous personal decision.

Union military intelligence records from 1864 revealed E served as a guide for Union forces during operations along the South Carolina coast.

His knowledge of Charleston’s waterways and defenses proved invaluable during several missions.

He risked everything, Rebecca said, studying the brief commenation, noting exceptional service by a young negro guide formerly of Charleston.

As Sherman’s march cut through Georgia and the Carolinas, Elijah was attached to a unit documenting war damages and assisting formerly enslaved people fleeing plantations.

A photograph from this period showed Union officers with several black scouts.

One, a teenager standing slightly apart.

His face and profile but recognizable from the earlier photograph.

It’s him, Rebecca confirmed.

5 years older, but unmistakable.

Most poignant was a military chaplain’s report describing a unit’s return to a plantation near Magnolia Creek.

young negro guide became visibly distressed upon approaching former residents, requested permission to search property records, which was granted.

He retrieved several documents and a small wooden figure before the main house was burned.

He went back, Daniel said, to reclaim pieces of his past.

As the war ended, Elijah’s trail led to a Freedman’s Bureau school in Charleston, the city he had fled now transformed by defeat and occupation.

Bureau records listed Elijah Freeman, age 16, as both student and teaching assistant.

He took the surname Freeman, Rebecca noted.

Many formerly enslaved people chose names reflecting their new status.

A teachers report praised his exceptional progress and natural teaching ability while noting Car’s deep knowledge of both bondage and freedom that lends gravity to his interactions with both students and adults.

Most significant was Elijah’s application to a special program sponsoring promising Freriedman’s Bureau students to continue education in northern institutions.

In his own handwriting, careful precise, he wrote, “I seek education not only for myself, but to ensure others like me will never again be denied the power of knowledge.” His application included a personal reference from his former teacher, Hannah Wells, and surprisingly a letter from Emily Fletcher, who had relocated to Philadelphia after her husband’s financial ruin and death.

“The boy Elijah, whom I once wrongfully held in bondage, deserves every opportunity denied him by an unjust system I regret participating in,” she wrote.

“His mind is remarkable, his character forged in circumstances no child should endure.

She acknowledged her wrong,” Rebecca said softly and tried to make some amends.

Elijah’s application was accepted, opening the next chapter in his extraordinary journey.

By 1868, Elijah Freeman was enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio, one of the few institutions accepting black students.

“Col records showed him studying education in history, maintaining excellent academic standing despite arriving with a fragmented formal education.” “His application essay has been preserved,” Rebecca told Daniel as they reviewed digitized documents.

“It’s extraordinary.” In eloquent handwriting, Elijah had written, “I carry within me two children.

The enslaved boy who stood for a photograph, knowing he would be sold the next day, and the free man who now writes these words, “Education is the bridge between these two selves and between our nation’s shameful past and its possible future.” A professor’s note in his file observed, “Freeman brings unique perspective to historical discussions.

When other students speak of slavery as an abstract concept, he quietly corrects factual misunderstandings with firsthand knowledge that silences the classroom.” Elijah’s college years revealed his growing interest in photography and documentation.

He apprenticed with a local photographer while studying, learning the technical aspects of the medium that had first captured his image as a child.

Most revealing was his thesis topic, photographic evidence, documentation as resistance in American slavery.

His advisers comments noted, “Freeman’s analysis of how enslaved people and their allies used visual documentation to expose the realities of slavery is groundbreaking, informed by personal experience few scholars possess.

After graduation in 1872, Elijah accepted a teaching position at a Freriedman’s school in Washington DC, where education records showed him introducing innovative methods, including using photography to document student progress and community development.

He transformed the medium that once objectified him into a tool for empowerment, Rebecca observed.

A newspaper article from 1875 mentioned Professor E.

Freeman’s photographic exhibition at Howard University, documenting the rapid advancement of colored schools throughout the South.

Most significant was Elijah’s growing collection of photographs and documents related to formerly enslaved people’s experiences, personal testimonies, family reunifications, educational achievements, creating what he called, in a letter, an archive of freedom to balance the overwhelming documentation of bondage.

He was creating a counternarrative.

Rebecca explained to her department, “While most historical documentation of slavery came from the perspective of slave owners, Elijah was preserving the experiences and achievements of the formerly enslaved.

As his reputation grew, so did his mission to preserve these stories before they disappeared from living memory.

By the 1880s, Professor Elijah Freeman had established the Freeman Historical Collection at Howard University, one of the first archives dedicated to documenting African-American experiences from the perspective of the communities themselves.

“His approach was revolutionary,” Rebecca explained during her presentation to museum curators.

While most institutions collected plantation records and slave owner accounts, Freeman focused on gathering personal narratives, photographs, and documents from formerly enslaved people.

Newspaper accounts described Freeman traveling throughout the South, carrying his camera and recording equipment to document elderly, formerly enslaved people’s stories before they were lost.

A journal entry revealed his urgency.

Each passing year claims more voices that can speak directly of bondage.

Their testimonies must be preserved if future generations are to understand the full human cost of slavery.

Most poignant was Freeman’s return to Charleston in 1885 to document the former Fletcher household.

An interview remaining community members who remembered the antibbellum period.

His field notes recorded, “Standing before the house where I once served produces a storm of emotions I cannot fully capture in words.

The boy I was would never have imagined the man I’ve become returning with a professor’s title and the freedom to document rather than be documented.” During this trip, Freeman also visited Magnolia Creek Plantation, now abandoned and decaying.

His photograph of the ruined main house was captioned, “Where William played while I awaited sail, both of us children yet worlds apart.” His most significant work came in documenting reconstruction’s achievements and subsequent challenges as southern states began implementing Jim Crow laws.

Freeman’s photographs and writings created a vital historical record of this pivotal period, capturing both progress and backlash.

He understood he was witnessing crucial historical transitions, Rebecca noted, and that dominant narratives would likely erase or distort them without proper documentation.

are.

By the 1890s, Freeman had compiled an extraordinary archive that challenged the emerging lost cause mythology romanticizing the antibbellum south.

His collection included the original photograph from Magnolia Creek, the image that had started his journey and now served as a powerful teaching tool in his lectures about slavery’s reality.

When asked by a student why he kept the painful photograph, Freeman reportedly answered, “Because the auction notice in the corner tells a truth many wish to forget, and the eyes of that child remind me daily of our obligation to remember.” In 1901, at age 52, Professor Freeman received an unexpected letter that would lead to an extraordinary reunion.

The letter postmarked from Boston read, “Dear Professor Freeman, I believe you may be the boy Elijah from my father’s photograph taken at Magnolia Creek in 1857.

I am William Harrison Jr., and I have spent years wondering what became of you.” Rebecca discovered this correspondence in Freeman’s archive papers along with his careful draft response.

Mr.

Harrison, your letter has found the boy from that photograph, though he exists now only in memory.

The man who writes to you today would welcome a meeting, though I wonder what you seek from such an encounter.

After several exchanges, they arranged to meet at Howard University, where Freeman had insisted the reunion take place, on grounds where I am professor, not property, as he wrote to a colleague.

A photographer documented their meeting, the former plantation heir, now a businessman in his 50s, and the former enslaved child, now a distinguished academic.

The photograph showed two middle-aged men seated in Freeman’s office, surrounded by books and historical artifacts.

Freeman’s journal entry afterward was revealing, “Harrison remembers our childhood differently, recalls us as playmates, despite the vast chasm between our circumstances.

Yet, he seems genuinely interested in understanding.

He brought his father’s plantation journals, which contain information about my parents, I never knew.” For this alone, the discomfort of our meeting was worthwhile.

Most significant was what William Harrison revealed about the photograph itself.

His father had commissioned it specifically because Elijah was to be sold, a remembrance of a child William had grown attached to.

The auction notice had indeed fallen accidentally into the frame, but the photographer had noticed and subtly ensured it remained visible.

The photograph that documented my sale became the evidence that preserved my memory, Freeman wrote.

And now completes a circle neither the photographer nor my former masters could have imagined.

After their meeting, Harrison donated his family’s plantation records to Freeman’s collection, an unprecedented transfer of historical materials that allowed Freeman to document aspects of plantation life rarely accessible to black historians of the period.

Freeman’s collection grew to include this remarkable correspondence and reunion documentation, which he framed as evidence that history is not merely what happened, but our continuing relationship with the past, a conversation across time that can occasionally bend toward reconciliation and truth.

In the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture, Rebecca stood before the newly installed exhibition documented Professor Elijah Freeman and the photographic record of freedom.

The original Magnolia Creek photograph held the central position, the image of a child about to be sold now properly contextualized within the extraordinary life that followed.

Beside it, Hung Freeman’s own photographs documenting reconstruction, education initiatives, and formerly enslaved people’s testimonies.

“What moves me most?” Rebecca told the gathering of historians and descendants at the exhibition opening is how Freeman transformed documentation from a tool of objectification into one of empowerment and historical preservation.

The exhibition traced Freeman’s remarkable journey from enslaved child to educator, photographer, and pioneering historian.

His Freeman collection had grown into one of the most significant archives of African-American experience, preserving countless voices that might otherwise have been lost.

Most powerful was the section displaying Freeman’s own reflections on the meaning of his life’s work written in 1910.

I began as a subject of history photographed as property documented in ledgers and auction notices.

I will end as an author of history, having created an archive that future generations may use to understand not just what was done to us, but what we did, thought, created, and dreamed despite it all.

Among the attendees were descendants of both the Freeman and Harrison families, the living legacy of both the enslaved and enslaver.

Now united in honoring a shared if painful history, Elizabeth Freeman Davis, Elijah’s great-granddaughter and a historian herself, stood before the original photograph that had started it all.

My great-grandfather would be proud to see his work continuing.

She told Rebecca, “Not just preserving the past, but using it to understand our present.” As visitors moved through the exhibition, many paused longest before the original photograph, studying the auction notice in the corner in the knowing eyes of the child who would transform his documentation into a lifelong mission of historical preservation and truthtelling.

The small boy from Magnolia Creek Plantation, positioned as a prop in a white child’s portrait, had indeed been remembered not as property to be sold, but as a pioneer who ensured that enslaved people’s experiences would be documented in their full humanity, complexity, and truth.

Through the power of a single photograph and the remarkable life that followed, visitors could trace a path from objectification to agency, from property to professor, revealing a story of resilience and reclamation that had almost been lost to History.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load