The Photograph That Changed Everything

Dr.

Natalie Chen, senior curator of photography at the National Museum of American History, had spent her career processing thousands of historical images.

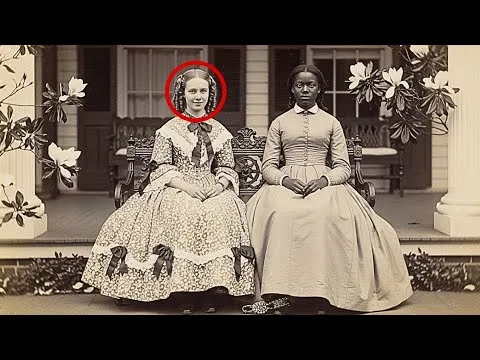

But the 1853 daguerreotype she scanned one quiet afternoon was different.

Two teenage girls sat side by side on an ornate plantation veranda bench: on the left, a white girl of about 14, her blonde hair arranged in ringlets and her dress a masterpiece of Victorian fashion.

On the right, a Black girl of about 15, dressed elegantly but less ornately.

Natalie paused, struck by the unusual composition.

Most antebellum photographs showed clear power relationships—masters and servants, never equals sharing a bench.

This image had already been celebrated in publications as a rare depiction of interracial friendship in pre–Civil War Louisiana.

But as Natalie zoomed in to inspect the image’s quality, a detail caught her eye: a metallic object, partially visible beneath the Black girl’s hem.

Adjusting the contrast and sharpness, Natalie realized it was not jewelry, but an ornate metal shackle disguised with decorative elements—a restraint attached to the girl’s ankle.

The supposedly heartwarming image of friendship was suddenly transformed into documentation of captivity, disguised as companionship.

Chapter 1: The Search for Truth Behind the Image

Natalie couldn’t shake the haunted expression she now saw in the Black girl’s eyes.

What had seemed like Victorian stoicism now read as resigned suffering, hidden in plain sight for over 170 years.

She dug into the museum’s archives for any documentation related to the Montgomery plantation photograph.

The original acquisition notes from 1972 described it as “Caroline Montgomery with her companion Harriet, 1853.” The accompanying letter from Montgomery descendants claimed Harriet was a “favored house servant, treated almost as family”—a sanitized narrative, as Dr.

James Whitaker, the museum’s director of historical research, observed.

Natalie and James found no mention of the ankle restraint in any documentation.

But plantation inventories revealed a 1851 entry: “Purchased girl, age 13, $800.

Intended companion for Miss Caroline.” A personal diary belonging to Caroline’s mother described “acquiring a suitable companion for Caroline,” and praised the “special arrangement” crafted to be both “secure and befitting her position”—referring to the decorative shackle.

Caroline and Harriet spent afternoons reading together, but the diary made clear that Harriet’s education was carefully controlled, and her “gold filigree” restraint was chosen to be elegant enough for public appearances.

Natalie realized Harriet wasn’t just enslaved—she was forced to perform friendship while literally chained.

A pet slave for a lonely plantation daughter.

Chapter 2: Harriet’s Voice Emerges

Natalie turned to the National Archives, searching for narratives from formerly enslaved people.

After days combing through Federal Writers Project interviews, she found one from 1937 in Chicago: Harriet Johnson, born in Louisiana, matched the girl in the photograph.

“I was purchased special to be a friend to the daughter, Miss Caroline.

They dressed me fine, taught me to read some, though it was against the law.

But don’t let that fool you about kindness.

I wore gold chain on my ankle for four years, only removed when I was safely locked in my room at night.”

Harriet’s account continued: “They called it my special bracelet.

Said it was a privilege to wear gold when other slaves wore iron.

But a chain is a chain, no matter how pretty.

Miss Caroline liked to pretend we were true friends.

Maybe she even believed it.

But friends don’t own friends.”

Harriet described being required to speak properly, dress elegantly, and accompany Caroline everywhere—meals, social events, lessons.

She was displayed as evidence of the Montgomery family’s “enlightened” treatment, while the shackle ensured she couldn’t escape.

The photographer came for Caroline’s 14th birthday: “They dressed me in one of my finest dresses, still plain next to hers, and posed us together.

Miss Caroline was proud of that picture, said it showed how special our friendship was.

Never saw that the chain on my ankle told the true story.”

Harriet eventually escaped during the Civil War, fled north, married, raised children, and told her story decades later.

“People today might look at the picture and see two girls being friends, not knowing one was property to the other.

That’s how slavery worked.

Sometimes it dressed itself up pretty, but underneath was always chains.”

Chapter 3: Uncovering a Widespread Practice

Harriet’s testimony energized Natalie’s research.

She assembled a team—Dr.

Marcus Johnson, expert on enslavement practices, and Emily Parker, digital imaging specialist.

They developed an algorithm to scan the museum’s archives for similar images: formal portraits showing Black and white individuals in close proximity, especially children and young women.

Of 43 potential matches, seven clearly showed disguised restraints—decorative shackles, chains masked as jewelry, gold ribbons that were actually metal bands.

Marcus explained that “companionate enslavement” was a recognized practice: enslaved children forced to serve not just as servants, but as emotional companions to white children.

The psychological cruelty was staggering—forcing someone to perform friendship while keeping them in bondage.

Plantation records from Georgia, Virginia, and the Carolinas referenced “companion acquisitions” and “appropriate restraint practices.” A Virginia plantation diary described a “bright young girl” purchased for Mary’s companion, with a silversmith crafting a chain “that won’t embarrass us in society.”

It was a status symbol among elite families—having an elegantly dressed, well-spoken enslaved companion for your daughter demonstrated wealth and supposed benevolence, all while maintaining absolute control.

Chapter 4: The Emotional Cost

The team found these arrangements most common among wealthy families with daughters aged 10 to 16.

The enslaved companions were typically slightly older, selected for intelligence and appearance, given privileges like fine clothing and literacy—but always with the underlying reality of ownership and restraint.

Auction records showed enslaved children advertised as “suitable companions” commanded higher prices, with listings praising “well-mannered, refined features or pleasing temperament”—euphemisms for children who could convincingly perform the role of friend.

Photographs in family albums presented these companions as evidence of benevolent treatment, with restraints carefully positioned out of frame or disguised as jewelry.

These families weren’t hiding the arrangements—they were proud of them, seeing them as enlightened.

It was the ultimate display of power: not just owning someone’s body, but claiming ownership of their emotions and relationships, forcing them to simulate friendship while never letting them forget they were property.

Chapter 5: The Museum Confronts the Truth

Natalie presented her team’s findings to the museum’s exhibition committee.

The projected image of Harriet and Caroline, with the enhanced section showing the shackle, made the implications undeniable.

“This completely changes how we should display and interpret this photograph,” Natalie insisted, “and potentially dozens of others in our collection.”

Richard Townsend, the museum’s senior director, looked troubled.

The Montgomery collection had been donated with considerable funding, and family descendants sat on the board.

“All the more reason to be truthful,” Natalie countered.

“This isn’t just about one photograph.

It’s about correcting a fundamental misrepresentation of history.”

Dr.

Eliza Washington, head of African-American history collections, agreed.

“We have a responsibility to present these images accurately, especially given Harriet’s own testimony.

Anything less would perpetuate the erasure of her experience.”

After hours of debate, the committee approved a special exhibition—Hidden in Plain Sight—centered on the Montgomery photograph and others like it, presenting original interpretations alongside the new evidence: disguised restraints, forced companionship, and Harriet’s own words.

Chapter 6: Family Reckoning

Natalie and Director Townsend met with Montgomery family representatives, who initially expressed outrage.

“You’re defaming my ancestors based on a shadow in an old photograph,” Eleanor Montgomery Williams insisted.

Natalie calmly displayed the enhanced image and Harriet’s testimony.

“The details match precisely—the dates, names, location, even the description of the gold filigree restraint.

We also found your great-great-grandmother’s diary entries describing the arrangement.”

After tense negotiations, a compromise emerged: the family would not block the exhibition, but would include a statement acknowledging their ancestors’ participation in a morally unacceptable system, while noting they were products of their time.

As Eleanor left, she told Natalie, “You think you’re doing something noble, but you’re just stirring up painful history better left buried.”

Natalie replied, “Harriet couldn’t tell her story while she was chained, but she lived to make sure it was recorded.

Don’t you think she deserves to be heard now?”

Chapter 7: Revealing the Hidden System

The team expanded their research, reaching out to other institutions and private archives.

Their inquiries generated both interest and resistance, as curators grappled with the implications for their own historical photographs.

The Historical Society of Louisiana identified three more images with similar characteristics.

Auction records and estate inventories listed companion restraints among valuables.

Oral histories described companions locked in at night, wearing “tokens” marking them as belonging to the daughter of the house.

The most powerful breakthrough came when they located Gloria Thompson, a descendant of another companion, Rachel, who had been forced into a similar arrangement in Virginia.

Gloria preserved a decorative gold cuff with a locking mechanism, passed down through generations.

Rachel escaped during the war and kept the cuff so her children would “never forget what pretty things could hide.”

The team identified over 60 clear examples of the practice, spanning from the 1830s to the Civil War, concentrated among elite families in Virginia, Georgia, and Louisiana.

The physical evidence, combined with written and oral testimonies, painted a comprehensive picture of a widespread, previously unrecognized aspect of slavery’s psychological control.

Chapter 8: The Exhibition—Hidden in Plain Sight

On opening night, the National Museum of American History buzzed with anticipation.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Captive Companions featured the Montgomery Plantation photograph as its centerpiece, enlarged with interactive lighting that illuminated the disguised shackle.

Similar photographs were displayed, with hidden restraints revealed through enhancement.

Beside each image were the stories of the enslaved girls, drawn from historical records, diaries, and their own testimonies.

Harriet’s narrative featured prominently, her words displayed alongside the photograph where she’d been forced to pose as Caroline’s friend.

“We’re not just showing what was hidden in these photographs,” Natalie explained to a reporter.

“We’re revealing how history itself can hide disturbing truths behind seemingly innocent images.

These girls were required to perform friendship while being physically restrained and emotionally manipulated.”

Gloria Thompson’s family heirloom, the golden restraint cuff, was displayed in a central case.

Visitors could examine its ornate exterior and the hidden locking mechanism that transformed jewelry into a tool of captivity.

Interactive stations allowed people to examine unaltered historical photographs and discover hidden restraints for themselves.

The exhibition also featured commentary on how historical narratives are constructed, challenged, and revised as new evidence emerges.

Reactions were powerful and varied—some visitors wept, others engaged in intense debate, descendants of plantation families expressed discomfort, while descendants of enslaved people thanked the museum for finally telling this hidden story.

Chapter 9: Legacy and Impact

One year after the exhibition opened, Hidden in Plain Sight had traveled to seven major museums, sparking research projects and re-evaluations of historical photography collections nationwide.

Over 40 additional companion photographs had been identified, creating a comprehensive understanding of what had once been an invisible practice.

The project inspired a broader movement to re-examine seemingly benign historical narratives and images for hidden evidence of oppression and resistance.

Museums and universities developed new protocols for analyzing photographs, looking beyond the obvious to find stories concealed in margins and details.

A young intern delivered a package to Natalie—Caroline Montgomery’s personal diary, discovered by Eliza Montgomery, a descendant who had been moved by the exhibition.

The diary revealed a complex relationship: moments of genuine affection alongside disturbing expressions of ownership and control.

Caroline wrote, “Harriet looked sad today.

I told her she’s lucky to be my friend instead of working in the fields.

She said nothing, but I saw her touching her ankle chain when she thought I wasn’t looking.

Sometimes I wish she didn’t have to wear it, but mother says it’s necessary.

I gave her a ribbon to tie around it to make it prettier.”

Natalie added the diary to the growing archive, ensuring both Harriet’s and Caroline’s perspectives were preserved.

The true power of their work was not just exposing hidden chains, but revealing the full humanity of all involved—trapped in different ways by history’s terrible bindings.

The Image That Refused to Stay Silent

As Natalie placed the diary in an archival box, she thought about the photograph that started everything—a seemingly innocent image that, once truly seen, could never be viewed the same way again.

Hidden in Plain Sight was more than an exhibition.

It was a reckoning, a reminder that history’s most comfortable stories often conceal the darkest truths.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load