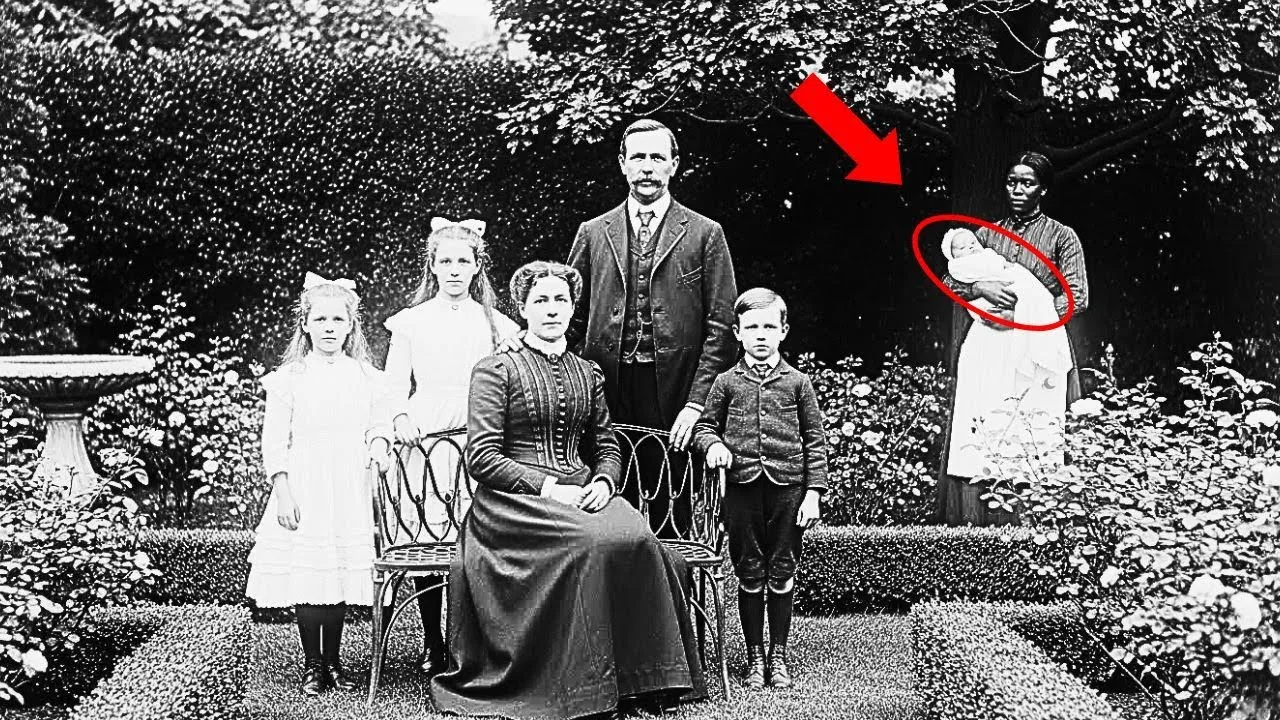

This mysterious 1901 photo holds a secret that experts have tried to explain for decades

Dr.Elena Vasquez had spent 20 years restoring historical photographs, but she had never seen anything quite like this.

It was a humid August morning in 2024, and she sat in her studio in Cambridge, Massachusetts, examining a photograph that had been brought to her by the Boston Historical Society.

The image dated 1901 showed the wealthy Thornton family of Beacon Hill posing in their elaborate garden.

The photograph was a masterpiece of early 20th century portraiture.

The Thornton family stood arranged on their manicured lawn, the patriarch Richard Thornon in the center, his wife Catherine beside him, their three daughters in white laced dresses, and a young boy of perhaps 5 years old standing between the parents.

Behind them rose their impressive brownstone mansion, and carefully trimmed hedges framed the composition.

Elena had been hired to digitally restore the photograph, which had suffered water damage and fading over the decades.

She scanned the image at extremely high resolution, then began the painstaking work of removing stains, adjusting contrast, and sharpening details that time had blurred.

It was during this process, while working on the background elements that she noticed something unusual.

In the deep shadows beneath a large oak tree at the edge of the frame, there appeared to be a figure, someone the original viewers of the photograph would likely have overlooked or dismissed as a shadow or garden ornament.

Elellanena increased the magnification and applied advanced digital enhancement techniques, carefully brightening the shadowed area while preserving detail.

Her breath caught as the figure became clear.

It was a woman, a black woman, dressed in simple domestic servants clothing.

She stood partially concealed behind the tree trunk, but her posture and position were deliberate, not accidental.

Most remarkably, she was holding an infant wrapped in white cloth.

The woman’s face, now visible thanks to digital enhancement, showed an expression Elena found difficult to read.

sadness mixed with something else.

Pride perhaps or defiance.

Ellena sat back from her computer screen, her mind racing.

The presence of a black domestic worker in a wealthy white family’s photograph wouldn’t normally be surprising.

Many such photographs from that era included servants, usually positioned at the edges or background to indicate the family’s prosperity.

But there was something about this woman’s placement that seemed intentional yet hidden, and something about the way she held that infant that suggested this was more than a simple inclusion of household staff.

Elena zoomed in on the baby in the woman’s arms.

The infant’s features were difficult to distinguish, but the child appeared quite light-skinned.

She then examined the young boy standing with the Thornon family.

He looked to be about 5 years old, with light brown hair and features that matched the family patriarchs.

A theory began forming in Elena’s mind, one that made her heart race.

She pulled up the original work order from the historical society.

The photograph had been donated by the Thornon family descendants as part of a larger collection documenting prominent Boston families.

The accompanying documentation identified the people in the main group, Richard Thornon, his wife Catherine, their daughters Margaret, Elizabeth, and Anne, and their nephew James, whose parents had supposedly died in a collar outbreak, leaving him orphaned.

But there was no mention of the woman in the shadows, no mention of the infant she held.

Elena spent the rest of the day researching the Thornon family.

Richard Thornton had been a successful textile merchant, one of Boston’s wealthiest men in the early 1900s.

His family had been prominent in Boston society, attending the right churches, hosting elaborate parties, serving on charitable boards.

Catherine came from old Boston money, her lineage traceable to colonial times.

The family had employed numerous domestic servants, as was customary for households of their status.

Helena found census records listing several black servants working in the Thornon household in 1900 and 1910.

But identifying which woman appeared in the photograph would require more investigation.

As evening fell, Elena printed a highresolution copy of the enhanced photograph and pinned it to her wall.

She couldn’t stop looking at that woman in the shadows, at the baby in her arms, at the expression on her face that seemed to Elena like someone trying to claim something that had been taken from her, even if only through the medium of a photograph.

Something important had happened in this family, something that had been deliberately hidden in plain sight for over a century.

and Elena was determined to uncover the truth.

Elellena contacted the Boston Historical Society the following morning, speaking with the curator who had sent her the photograph.

“Dr.

Patricia Chen listened carefully as Elena described what she had discovered in the enhanced image.

I’ve examined hundreds of photographs from this period,” Elena explained.

“And the positioning of this woman feels intentional.

She’s not casually in the background.

She’s been carefully placed where she would be visible, but easily overlooked, especially in a print of lower quality than the original.” Patricia was intrigued.

The Thornton family donated this collection only 6 months ago.

The current family members claimed they were simply clearing out an old estate and thought the historical society might want the materials.

They didn’t express any particular interest in the contents.

Do you think there’s a story here worth investigating? I’m certain of it, Elena replied.

But I’ll need access to more records, employment documents, birth certificates, anything that might identify the woman in the photograph and the infant she’s holding.

Patricia agreed to help.

Together, they began searching through the Thornon family papers that had been donated along with the photographs.

There were business ledgers, social correspondents, property records, and household account books spanning from 1890 to 1920.

In a household account book from 1901, they found regular payments to several domestic servants, including a notation, Clare Washington, Cook, and housemade $8 per month plus room.

The entry began in 1899 and continued through 1902 when it abruptly stopped with a single word written in the margin, dismissed.

Elena felt a surge of recognition, Clara Washington.

She photographed the page, noting the dates carefully.

If Clara had been dismissed in 1902, and if she was the woman in the 1901 photograph, then something significant must have happened in that household.

They continued searching and found something even more revealing in a collection of personal letters.

A letter from Katherine Thornon to her sister in Philadelphia dated March 1901 contained a passage that made Ellena’s hands tremble.

We have taken in Richard’s nephew James, as you know, following the tragic loss of his parents.

The boy is adjusting well to our household, though the circumstances of his arrival have been complicated by unfortunate rumors.

I assure you, these rumors are entirely without foundation.

James is our blood relation, and we are providing him the upbringing his station deserves.

We have had to make certain household adjustments to ensure propriety is maintained.

The letter was carefully worded, but Elena could read between the lines.

Rumors, household adjustments, the defensive assertion that James was a blood relation.

This was a family managing a scandal.

Patricia discovered another crucial piece of evidence in the birth records at Boston City Hall.

There was indeed a James Thornon, born in February 1896, listed as the son of Richard Thornton’s deceased brother.

But when Patricia requested the death certificates for James’ supposed parents, she found something strange.

They had died in 1898, not 1896.

If James had been born in 1896, he would have been 2 years old when his parents died, not a newborn orphan, as the family story suggested.

“This doesn’t make sense,” Patricia said, spreading the documents across the table.

“The timeline is wrong.

And look at this.

James’ birth certificate lists his place of birth as Boston, but the parent supposedly lived in New York at the time.

Why would the mother have come to Boston to give birth?” Elena studied the birth certificate more carefully.

Something about it looked odd.

The handwriting seemed slightly different from other certificates from the same period, and there was a notation in the margin that had been partially obscured.

Amended record.

Oh, this birth certificate was altered, Elena said quietly.

Someone changed the original information.

They sat in silence, the implications settling over them.

A child born in 1896, raised as the nephew of the Thornon family, a birth certificate that had been amended, household servants dismissed, and a photograph showing a black woman holding an infant while positioned in the shadows of the family garden.

The pieces were beginning to form a picture, though not yet a complete one.

Helena needed to find out more about Clara Washington, the woman who had worked in the Thornon household and then been abruptly dismissed.

She needed to trace what had happened to James Thornon after 1901, and she needed to understand why this family had gone to such elaborate lengths to obscure the truth.

Elena spent the next week tracking down every record she could find related to Clara Washington.

The search proved challenging.

Washington was a common surname among black Bostononians, and Clare had left few traces in official records.

But Elena was persistent, and gradually a picture began to emerge.

Clara Washington had been born in Virginia in 1875.

The daughter of formerly enslaved people who had moved north after the Civil War.

She arrived in Boston in 1897, seeking work as a domestic servant.

By 1899, she was employed by the Thornon family, working as both cook and housemmaid in their Beacon Hill mansion.

Elena found Clara listed in the 1900 census, residing at the Thornon address.

The census described her as single, negro, age 25, occupation domestic servant.

But there was a handwritten note in the margin of the census form that Elellena almost missed.

Infant daughter, not enumerated.

This notation was unusual and suggested the census taker had been uncertain how to categorize a child in the household.

The breakthrough came when Elena discovered birth records at Boston Lying in Hospital, institution that had provided maternity care to both wealthy and poor women in the early 1900s.

Among the records from February 1896 was an entry for Clara Washington Negro, age 21, delivered of a male infant.

The father’s name was listed as unknown.

But there was more.

Attached to the hospital record was a note from the attending physician.

Patient employed by R.

Thornton family.

Infant to remain with mother and Thornon household per family arrangement.

Fee paid by R.

Thornton.

Elellena’s theory was solidifying.

Clare had given birth to a son in February 1896 while working for the Thornon family.

Richard Thornton had paid the hospital fees, and somehow this infant had been transformed into James Thornon, the orphaned nephew.

She needed to find out what had happened to Clara after her dismissal in 1902.

Using city directories and church records, Elena traced Clara’s movements after she left the Thornon household.

She found Clara listed as residing in a boarding house in Boston South End in 1903, working as a laress.

But the trail went cold after that year.

No census entries, no employment records, no death certificate.

Then Patricia made a discovery that changed everything.

In the archives of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston, she found a baptismal record from 1896 for James Washington, son of Clara Washington.

The baptism had taken place just weeks after the hospital birth record, and it clearly identified the child’s surname as Washington, not Thornton.

The church records also contained something else, a letter from Clara to the church pastor, dated 1902.

Patricia photographed the letter and sent it to Ellena immediately.

Elena read Clara’s words with growing emotion.

Reverend Williams, I write to you in desperation, not knowing where else to turn.

You baptized my son James six years ago, and I have raised him with love despite the difficult circumstances of his birth.

His father, a man of prominent standing, who I will not name, provided support for us while demanding absolute secrecy about his paternity.

Now that man’s wife, has determined that my presence in their household is no longer acceptable.

She has insisted I be dismissed, and worse, she has told me that James will remain with them, to be raised as their own kin.

She says I am unfit to mother him, that he deserves better than a life with a colored laress.

She has offered me money to go quietly, to never speak of James’ true parentage, to never attempt to see him again.

Reverend, he is my son.

I carried him, birthed him, nursed him, raised him for six years, but I have no legal standing.

I am a negro woman with no family, no resources, no power.

The Thornons have everything: wealth, position, legal counsel.

If I fight them, they will destroy me and possibly harm James in the process.

If I accept their terms, I lose my child, but perhaps secure him a life of opportunity I could never provide.

I do not know what to do.

I pray for guidance, for strength, for some way to do right by my son, even as my heart breaks.

Elena wiped tears from her eyes.

The letter was dated October 1902, just around the time Clara had been dismissed from the Thornon household.

Clara had faced an impossible choice.

fight for her son and likely lose while damaging his future prospects, or walk away and let him be raised in privilege and comfort, never knowing his true mother.

The photograph from 1901 took on new meaning.

Now, that image had been taken just a year before Clara was forced out.

It showed Clara standing in the shadows holding an infant.

But which infant? Could there have been another child? Or was the photograph misdated? Elena needed to look at the photograph again more carefully, and she needed to find out what had happened to James Thornon as he grew up.

Did he ever learn the truth about Clara? Did he ever wonder about his origins? And most importantly, had Clara ever tried to see her son again, or had she disappeared from his life forever? Elena returned to her studio and pulled up the enhanced photograph on her computer screen.

She had been so focused on identifying the woman in the shadows that she hadn’t carefully examined every detail of the image.

Now, she looked more closely at the infant Clara was holding.

Using maximum magnification, Elena studied the baby’s features and the white christing gown it wore.

Then she compared this infant to the young boy standing with the Thornon family.

The child identified as 5-year-old James.

Her breath caught.

The infant in Clara’s arms could not be 5 years old.

The baby was clearly only a few months old at most.

But if James was born in 1896, he would have been five in 1901, matching the age of the boy in the main photograph.

Ellena felt a chill run down her spine.

There were two children in this photograph.

James, the 5-year-old boy standing with the Thornon family as their nephew, and a much younger infant in Clara’s arms.

She immediately called Patricia.

There’s another child, she said urgently.

Clara is holding an infant who is not James.

I need to find birth records from 1900 or 1901 for any child connected to the Thornon household.

Patricia understood immediately.

They reconvened at the historical society and began a systematic search through birth records from 1900 and 1901.

This time they knew what patterns to look for.

Any birth involving the Thornon family, any notation about domestic servants, any amended or unusual records.

It took two days, but they found it.

In March 1901, just months before the photograph was taken, Boston lying in hospital recorded the birth of a female infant to Clara Washington, negro domestic servant.

Once again, Richard Thornton had paid the hospital fees.

The father was listed as unknown, but the notation was identical to the one from James’ birth 5 years earlier.

Clara had given birth to a second child in 1901, another child fathered by Richard Thornton.

The infant in the photograph was Clara’s daughter.

Where is this child? Elena wondered aloud.

What happened to her? Patricia began searching adoption records, death certificates, anything that might trace the fate of Clara’s daughter.

The search proved difficult.

Adoption records from that era were often sealed or poorly maintained, and many children born to unwed mothers simply disappeared from official documentation.

Then Patricia found something in the records of the Boston Home for Colored Children, an orphanage that had operated in the early 1900s.

In their intake records from September 1901, there was an entry for female infant approximately 6 months old surrendered by mother Clara Washington, child in good health, adoption pending.

The timeline fit perfectly.

The photograph had been taken in the summer of 1901, showing Clara holding her infant daughter.

By September, just months later, Clara had been forced to surrender the child to an orphanage.

But there was more.

Attached to the intake record was a note.

Adoption finalized October 1901.

Child placed with family in New York.

Records sealed per family request.

Substantial donation received from anonymous benefactor to support orphanage operations.

Elena understood.

The Thornton had arranged for Clara’s daughter to be adopted away.

Had paid for the adoption to be expedited and the records sealed.

They had removed the second child from Clara’s life just as they had taken James.

But they had let Clara have one thing, that photograph.

They had allowed her to stand in the shadows of their garden, holding her infant daughter one last time, creating a permanent record of her motherhood.

even as they prepared to take that child away from her.

The photograph wasn’t just a family portrait, Elena said quietly.

It was Clara’s last chance to be seen as a mother, even if only in the margins, even if only in the shadows.

Someone in that family, maybe Richard himself, maybe even Catherine, understood that Clara deserved at least that much.

Patricia nodded slowly.

But why keep the photograph? Why not destroy it if it contained evidence of their secrets? Because someone wanted the truth preserved, Elena replied.

Even if it was hidden, even if it took more than a century to be discovered, someone wanted Clara’s motherhood documented.

Elena shifted her investigation to James Thornon, the son Clara had lost when he was 6 years old.

What had become of him? Had he lived his entire life believing he was Richard Thornton’s nephew, never knowing his mother had been dismissed from the household when he was a child? She began with census records, tracing James through the decades.

In 1910, at age 14, he appeared in the Thornon household, listed as nephew, attending preparatory school.

By 1920, at age 24, he had graduated from Harvard Law School and was working at a Boston law firm.

The 1930 census showed James Thornon, aged 34, married to a woman named Elizabeth, living in Boston’s Backbay neighborhood with two young children.

His occupation was listed as attorney.

He’d clearly achieved success and respectability, but there was something else in the 1930 census that caught Elena’s attention.

Under race, James was listed as white, but there was a small notation in the margin, so small it was barely visible, that read mulatto amended.

Someone had originally recorded James as mixed race, then changed it to white.

Elena’s heart raced.

Had there been questions about James’ racial identity? Had someone noticed that he didn’t look entirely white, or had rumors about his true parentage followed him into adulthood? She searched for newspaper archives, looking for any mention of James Thornon.

What she found astonished her.

In 1935, James had made headlines by taking on a controversial case, defending a black family who had been forcibly evicted from their home in a white Boston neighborhood.

The case had garnered significant attention because James, a white attorney from a prominent Boston family, had worked without payment to defend the black family against wealthy white property owners.

He had won the case, setting a precedent that weakened discriminatory housing practices.

Over the following decades, Ellen discovered that James Thornton had become one of Boston’s most prominent civil rights attorneys.

He had defended countless black clients, had fought against segregation in schools and public accommodations, and had been instrumental in several landmark cases that advanced racial justice in Massachusetts.

In 1954, the year of the Brown versus Board of Education decision, James had given a speech at the NOAACP’s Boston chapter that was covered by local newspapers.

Elena found the text of his speech in the archives.

I stand before you today as someone who has benefited from privilege all my life, the privilege of education, of social position, of being treated with respect simply because of the color of my skin.

But I also stand before you as someone who knows that justice delayed is justice denied.

That separate is inherently unequal and that we cannot rest until every person in this nation enjoys the full rights and dignity that our constitution promises.

The speech was powerful, but what struck Elena was a brief passage near the end.

There are people in our lives, people who love us, who sacrifice for us, whose contributions go unrecognized and unagnowledged.

We owe them a debt we can never fully repay.

The least we can do is fight for a world where such sacrifices are no longer necessary, where love and family are not constrained by the artificial boundaries of race.

Elena wondered if James had known.

Had he somehow learned about Clara? Had he dedicated his life to civil rights because he understood on some level that his own existence was the result of racial injustice.

She needed to find out more.

She needed to locate James’ descendants, if any existed, and learn whether the family had preserved any personal papers or documents that might reveal what James knew about his origins.

Elena located James Thornton’s grandson through public records.

Michael Thornton, age 68, was a retired professor of African-American history living in Cambridge, just a few miles from Elena’s studio.

When she called to explain her research, there was a long silence on the other end of the line.

“I think you should come to my house,” Michael finally said.

“There are things I need to show you.” Two days later, Elellena sat in Michael’s living room, surrounded by boxes of documents and photographs he had inherited from his grandfather.

Michael was a tall man with dark eyes and skin that could have been read as either white or light-skinned black, depending on the observer.

My grandfather died in 1975, Michael began, and he left me a sealed letter with instructions not to open it until after my father had passed away.

My father died 5 years ago, and I finally opened the letter.

What I read completely changed my understanding of my family history.

He handed Elena a yellowed envelope.

Inside was a letter in James Thornton’s handwriting dated 1974 written when he was 78 years old.

My dear Michael, by the time you read this, I will be gone and so will your father who never knew the full truth of our family’s origins.

I write to you because you are a historian because you have dedicated your life to uncovering difficult truths.

And because I believe you will understand why I kept this secret for so long.

I am not who the world believes me to be.

I am not the orphaned nephew of Richard and Katherine Thornton.

I am the son of Richard Thornton and a black woman named Clara Washington who worked in our household.

Clara was my mother, though I was raised to call her by her first name and treat her as a servant until she was dismissed when I was 6 years old.

I did not learn this truth until I was 30 years old.

In 1932, a woman approached me outside my law office.

She was elderly, frail, and I did not recognize her.

She told me her name was Clara Washington and that she was my mother.

She showed me documents, my original baptismal record, a letter she had written to her pastor, and a photograph of herself holding me as an infant in the garden of the Thornton house.

At first, I did not believe her.

The claim seemed impossible.

But she provided details about my childhood that only someone intimately connected to me could have known, the names of my favorite toys, a song she used to sing to me, a birthmark on my shoulder that no one else would have seen.

I spent weeks investigating her claims, examining birth records, speaking with old servants who had worked in the Thornon household.

Everything she told me proved to be true.

I was the son of a black woman raised as white, given every privilege while my mother was forced to disappear from my life.

My first reaction was anger at Richard Thornton, at Catherine, at everyone who had participated in this deception.

But Clara asked me not to be angry.

She said she had made peace with what happened, that she had watched from a distance as I grew up, attended university, became a lawyer.

She said she was proud of me and that she had never regretted carrying me, birthing me, loving me for the six years we had together.

She also told me about my sister, a daughter she had birthed 5 years after me, also fathered by Richard Thornton.

That child had been taken from her and adopted away.

Clara had tried to find her for years but never succeeded.

She showed me a photograph, the same one I now keep in my desk, showing her holding an infant in the Thornon Garden.

My sister, she said, was the baby in her arms.

I spent the last years of Clara’s life visiting her regularly, learning about her experiences, understanding the impossible choices she had faced.

She died in 1935 and I was able to be with her at the end, holding her hand, calling her mother for the first time since I was 6 years old.

After her death, I dedicated myself to fighting the kinds of injustices she had endured.

I became a civil rights attorney because I understood personally how the color line destroyed families.

How racial prejudice forced people into impossible situations.

How systemic racism denied people their basic human dignity.

Michael, you have chosen to study African-American history.

Now you know that you’re part of that history.

Clara Washington was your great-g grandandmother.

You carry her blood, her strength, her resilience.

I have lived my life as a white man because that is how I was raised.

But I want you to know the truth.

I want you to honor Clara’s memory.

and I want you to find my sister, if any trace of her remains.

Your grandfather, James.

Elellanena sat in stunned silence.

Michael had tears running down his face.

I’ve been searching for my great aunt for 5 years, he said.

I’ve traced adoption records, searched for children adopted from the Boston home for colored children in 1901.

Tried to find any connection, but the records are sealed or lost.

I’ve hit dead ends everywhere.

Elena thought about the photograph, about Clara standing in the shadows holding her infant daughter.

That photograph is the key, she said.

It’s the only visual evidence of your great aunt’s existence.

If we can get it properly publicized, if we can reach out to genealogologists and historians, someone might recognize a family story or have records that connect.” Michael nodded slowly.

“My grandfather spent 40 years fighting for civil rights, never publicly revealing his own connection to the black community.

He lived with that secret, honored Clara privately while presenting as white publicly.

And now you’ve discovered the photograph that proves everything he wrote in this letter.

There’s something else, Elena said carefully.

Your grandfather became one of Boston’s most important civil rights attorneys.

His work changed lives, changed laws, changed this city.

That legacy came directly from Clara.

From understanding what she endured, from knowing that his very existence was the result of exploitation and injustice that he spent his life fighting against Clara’s legacy, Michael said softly.

Not the Thornton.

Everything James accomplished came from her strength, her sacrifice, her love.

Elellanena and Michael spent the next three months preparing to reveal the truth about the 1901 photograph.

They gathered all the evidence, birth records, hospital documents, Clara’s letters, James confession, the photograph itself, and verified every detail.

Michael contacted other family members, some of whom were shocked by the revelation, others who admitted they had always sensed there was something unusual about the family history.

In November 2024, the Boston Historical Society held a press conference to announce the discovery.

Elena presented the photograph, now fully restored and enhanced, showing Clara Washington standing in the shadows, holding her infant daughter while the Thornton family posed in the foreground with her son, James.

The story made national headlines.

Major newspapers ran features about the photograph and the secret it had concealed for 123 years.

Television news programs interviewed Elena and Michael.

The image went viral on social media, sparking conversations about hidden histories, racial injustice, and the complexity of American families.

Um, but the most significant response came from an unexpected source.

3 days after the press conference, Michael received an email from a woman named Diane Roberts in Harlem, New York.

She was 79 years old, and she believed she might be descended from Clara Washington’s daughter.

Michael called her immediately, and what Diane told him made his hands shake.

Her grandmother, who had died in 1980, had been adopted as an infant from a Boston orphanage in 1901.

The grandmother had been told she was the daughter of a domestic servant who could not keep her, but no other details had been provided.

The grandmother had grown up in New York, married and had children, always wondering about her origins.

But there’s something else, Diane said.

My grandmother kept a small photograph that had apparently been given to the adopted family.

It shows a black woman in a garden, and my grandmother always said she thought it might be her birthother, though she could never prove it.

Michael asked Diane to send him the photograph.

When it arrived 2 days later, his heart nearly stopped.

It was a second print of the same 1901 photograph Elena had restored, but this one had been cropped to show only Clara and the infant with the Thornon family removed from the frame.

Someone, perhaps Richard Thornon, perhaps someone else in the family, had provided Clara’s daughter with a photograph of her mother holding her.

It had been an act of mercy, a way of ensuring that even though the child would be raised by strangers, she would at least have one image connecting her to the woman who had birthed her.

Elellena arranged for Diane to travel to Boston.

When she arrived, Michael met her at the airport, and they stared at each other with wonder.

They shared a great-g grandandmother.

They were family, separated for over a century by adoption, by racial prejudice, by deliberate concealment, but family nonetheless.

At the historical society, Elena showed Diane the full photograph, pointing out Clara in the shadows.

Diane wept as she looked at her great-g grandandmother’s face for the first time with certainty.

“She was beautiful,” Diane whispered.

“She was proud.

Look at how she’s holding that baby.

Holding me.

She loved me.

Even knowing she would have to give me up, she loved me.

Michael showed Diane the letter his grandfather James had written.

The confession revealing that he and Diane’s grandmother had been siblings, both children of Clara Washington and Richard Thornton, separated and raised in different worlds.

My grandmother lived her whole life as a black woman.

Diane said she married a black man, raised black children, lived through segregation and the civil rights movement.

She never knew she had a brother who was passing as white, who was fighting for civil rights from the other side of the color line.

“They were both Clara’s children,” Michael said softly.

“Both carrying her legacy, both shaped by the injustice that separated them from her.” James fought in the courts.

And your grandmother, what did she do? Diane smiled through her tears.

She was a teacher in Harlem for 40 years.

She taught hundreds of black children, told them they were brilliant and capable, prepared them for a world that would try to tell them otherwise.

she did for other people’s children what Clara couldn’t do for her.

She motherthered them, believed in them, fought for them.

Elena listened to this exchange and understood something profound.

Clara Washington had lost both her children to a system designed to destroy black families and deny black motherhood.

But both children, raised in different worlds, had spent their lives fighting against the injustices their mother had endured.

James in the legal system, Diane’s grandmother in the classroom, both had channeled Clara’s strength and love into work that changed lives.

The revelation of the photograph’s secret sparked a broader conversation about hidden black ancestry in white American families and the countless black mothers who had been separated from their children throughout American history.

Historians began examining other family photographs from the era, looking for similar instances of black domestic workers positioned at the margins, wondering how many other Claras might be hidden in plain sight.

Michael and Diane collaborated on a project to honor Clara’s memory.

They established the Clara Washington Foundation dedicated to researching and documenting cases of forced family separation during the Jim Crow era and supporting genealological research for African-Americans seeking to trace family members lost to adoption, migration, or racial violence.

They also worked with the Boston Historical Society to create a permanent exhibit about Clara, James, and the photograph.

The exhibit included the restored photograph, Clara’s letters, James’ confession, and contemporary reflections on how racial injustice had shaped American families.

Elellanena contributed to the exhibit by creating a series of enhanced images showing different aspects of the photograph.

Close-ups of Clara’s face, of the infant in her arms, of James standing with the Thornon family.

Each image was accompanied by historical context about domestic servitude, anti-misogenation practices, and the legal structures that had enabled men like Richard Thornton to father children with black women while facing no consequences.

The exhibit also addressed a difficult question.

How should Richard Thornon be remembered? He had fathered two children with Clara, a woman who worked in his household and had little power to refuse his advances.

Was this relationship consensual? Or had Clara been exploited by a man who held complete economic and social power over her? Clara’s letters provided some insight.

In one passage, she had written, “I do not claim to have been forced against my will, but neither can I claim I was free to refuse.

What freedom does a servant have when her employer demands her company? What choice exists when refusal might mean unemployment, homelessness, starvation? I cared for him.

I will not deny that.

But care that exists within such an imbalance of power cannot be called love.

Not truly.

The exhibit acknowledged this complexity, presenting Richard Thornon neither as a simple villain nor as a progressive man ahead of his time, but as someone who had participated in a system of racial and economic exploitation, even while occasionally showing mercy, paying Clara’s hospital bills, allowing her to keep James for 6 years, perhaps even arranging for the photograph that preserved her motherhood.

The photograph itself became iconic.

It was featured in textbooks, used in classrooms to teach about hidden histories and the complexity of race in America.

Copies were requested by museums across the country.

Artists created works inspired by Clara’s image, celebrating her dignity and mourning the children taken from her.

But perhaps the most meaningful legacy came from the descendants themselves.

Michael and Diane, united by the discovery of their shared ancestry, became close friends.

They introduced their children and grandchildren to each other, creating family connections that had been severed for over a century.

Michael’s children and grandchildren, who had grown up identifying as white, now had to grapple with their black ancestry and what it meant for their identity.

Some embraced it immediately, feeling it explained something they had always sensed about their family.

Others struggled with a revelation, unsure how to reconcile their lived experience as white people with the knowledge of their black great grandmother.

Diane’s family, who had always identified as black, welcomed the connection to Clara into the white descendants they had never known existed.

But there was also complexity here.

Pain at learning that Clara’s son had lived his life as white while their ancestor had endured the full weight of racial oppression.

Questions about what it meant that some of Clara’s descendants had benefited from whiteness while others had not.

These conversations were difficult, but Michael and Diane insisted they were necessary.

Clara’s legacy is not just in the photograph.

Michael said at one family gathering, “It’s in us, all of us, facing the truth of our history, understanding how racism shaped our family, and choosing to move forward together.” The publicity surrounding the photograph led to one final unexpected discovery.

A genealogologist in Connecticut named Thomas reached out to Michael after seeing news coverage of the story.

He had been researching his wife’s family tree and had discovered that her grandmother, adopted from the Boston Home for Colored Children in 1901, might be connected to the Thornon case.

Thomas sent documentation showing that his wife’s grandmother, Sarah, had been adopted by a black family in New York at exactly the time Clara’s daughter had been placed for adoption.

The adopted family had been told only that the baby’s mother was a domestic servant who could not keep her child, and that the father was unknown.

Michael immediately arranged to meet Thomas and his wife, Linda.

When they met, Michael showed them the photograph of Clara holding the infant, and Linda began to cry.

“My grandmother died when I was young,” Linda said.

But my mother told me that grandmother Sarah always felt like something was missing from her life.

She had been loved by her adoptive family, had a good childhood, but she always wondered about her birthother.

She kept that small photograph, the one of just Clara and the baby on her dresser her entire life.

My mother said grandmother would look at it and say she loved me.

I can see it in her eyes.

She didn’t want to give me away.

DNA testing confirmed what the document suggested.

Linda was Clara Washington’s great-g grandanddaughter, descended from the daughter Clara had been forced to surrender in 1901.

Linda, Diane, and Michael were all Clara’s descendants.

Three branches of a family tree that had been deliberately severed, but had somehow, against all odds, found each other again.

The three of them traveled to Boston together to visit Clara’s grave.

She was buried in a cemetery in Roxbury in a section reserved for black Bostononians.

Her headstone was simple, listing only her name and dates.

Clara Washington.

1875 1935.

Standing before Clara’s grave, Michael, Diane, and Linda held hands.

They told Clare that they had found each other, that her children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren were united again, that her story would be remembered and honored.

“You were hidden in the shadows of that photograph,” Michael said softly to Clara’s memory.

“But you refused to be completely invisible.

You insisted on being seen, on being acknowledged as a mother, even in the margins.

And because of that photograph, because of your courage, we found each other.

We found you.

They commissioned a new headstone for Clara.

One that listed not just her name, but her truth.

Clara Washington, 1875, 1935.

Beloved mother.

Her strength lives on in her descendants.

The dedication ceremony for the new headstone was attended by over a hundred people.

Descendants of Clara, descendants of James, former students of Dian’s grandmother, lawyers who had worked with James Thornon, historians who had been inspired by the photograph’s discovery.

Ellena spoke at the ceremony, explaining how she had found Clara hidden in the shadows of the family photograph, how digital restoration had revealed what had been obscured for 123 years.

Clara Washington was rendered invisible by a society that denied black women’s humanity, that denied black mothers rights to their own children, Ellena said.

But she found a way to make herself seen.

She stood in that garden holding her baby and insisted on being photographed.

That act of quiet resistance, that refusal to be completely erased, is what allowed her story to survive.

Clara knew she might never be able to tell her truth openly, but she made sure there would be evidence, made sure that someday someone might look closely enough to see her.

After the ceremony, Linda approached Elena with tears streaming down her face.

“Thank you,” she said simply.

“Thank you for looking closely.

Thank you for seeing my great-grandmother.

Thank you for refusing to let her stay hidden.

Elena embraced her, overwhelmed by the weight of what this discovery had meant to Clara’s descendants.

A photograph that she had been hired simply to restore had opened up an entire hidden history, had reunited a family separated for over a century, had brought recognition to a woman whose motherhood had been denied and erased.

Six months after the dedication of Clara’s headstone, Ellena’s work on the photograph was featured in a major museum exhibition titled Hidden Histories: Black Women in the Shadows of American Photography.

The exhibition included the Thornton Family Photograph alongside dozens of other images where black women appeared at the margins in the background, partially obscured or cropped out of frame.

The exhibition’s thesis was powerful.

These women had been deliberately rendered invisible by families and photographers who wanted to present a certain image of white respectability.

But their presence in the photographs, however marginal, provided evidence of the labor, the relationships, and the hidden family connections that white families wanted to deny.

Elena’s restoration of the Clara Washington photograph became the centerpiece of the exhibition.

Visitors could see both the original faded image where Clara was barely visible in the shadows and the restored enhanced version where her face and the infant in her arms were clearly visible.

The contrast demonstrated how much had been hidden and how technology could help reveal suppressed truths.

The exhibition traveled to museums across the country, and everywhere it went, people came forward with their own stories.

Families who had always suspected there was something hidden in their history, who had heard whispered stories about black ancestors who had been denied or erased, who had found mysterious photographs showing people at the margins whose identities had been lost.

Michael, Diane, and Linda participated in panel discussions at several exhibition venues, talking about what it meant to discover Clara’s story, how it had changed their understanding of their families and themselves.

Michael spoke about the burden and privilege of passing, about his grandfather James’ choice to live as white while fighting for black civil rights.

Diane talked about her grandmother’s life as a black woman who never knew she had a white passing brother working toward the same goals from a different position.

Linda discussed the pain of adoption and separation and the joy of finally knowing the truth about her great-g grandandmother’s love.

But the exhibition also sparked criticism.

Some argued that focusing on photographs of black domestic servants in white households perpetuated narratives of black subservience and white supremacy.

Others questioned whether it was appropriate to display images of women like Clara, who might not have wanted their exploitation documented and exhibited for public viewing.

Elena took these criticisms seriously.

In the exhibition catalog, she addressed them directly.

We must be careful not to reproduce the very eraser and exploitation we’re trying to document.

Clara Washington deserves to be remembered not just as a victim, not just as someone who was wronged, but as a full human being, a woman who loved, who made difficult choices, who showed tremendous strength, and who found a way to ensure her motherhood would be documented even when it was denied.

The photograph is evidence of injustice, yes, but it’s also evidence of Clara’s agency, her resistance, her refusal to be completely erased.

The exhibition concluded with a section on contemporary implications, showing how the legacy of forced family separation, denied black motherhood, and hidden black ancestry continued to affect American families.

It included stories of adoption, foster care, and child welfare systems that disproportionately separated black children from their families.

It drew connections between Clara’s experience in 1901 and ongoing patterns of systemic racism.

For Elena, the project had become much more than a photograph restoration job.

It had become a mission to honor Clara and the countless women like her whose stories had been buried, whose motherhood had been denied, whose presence had been erased from family histories.

She reflected on this in the final chapter of a book she wrote about the discovery.

When I first saw that shadow in the garden, I didn’t know I was looking at Clara Washington.

I didn’t know I was about to uncover a story of love and loss, exploitation and resistance, separation and reunion.

I simply saw something that didn’t look quite right, something that seemed hidden.

That’s what historians do.

We look at what’s been overlooked.

We question what’s been accepted.

We bring light to the shadows.

Clara Washington spent her life in the shadows of the Thornon family’s world.

But she made sure she was in that photograph.

She made sure that even if she was marginalized, even if she was nearly invisible, she was there.

and 123 years later, she was finally seen.

The book became required reading in many American history courses.

The photograph was reproduced in textbooks.

Clara’s story became part of the historical record, no longer hidden, no longer denied.

Michael, Diane, and Linda continued their work with the Clara Washington Foundation, helping other families research hidden histories and reconnect with ancestors who had been lost to adoption, migration, or deliberate erasure.

They funded DNA testing for people searching for family connections, supported genealological research, and advocated for opening sealed adoption records.

On the 125th anniversary of the photograph in 2026, descendants of Clara Washington gathered at the site of the former Thornon Mansion in Boston.

The building had been converted to a community center, and the garden where the photograph had been taken, was now a public park.

Over 50 people attended, descendants of both James and Sarah, now united as one family.

They planted a tree in Clara’s honor, installed a plaque telling her story and shared memories of how her legacy had shaped their lives.

Elena attended the gathering and was moved by the sight of Clara’s family, reunited across racial lines that had once seemed insurmountable, standing together in the very spot where Clara had stood holding her baby, insisting on being seen.

Clara Washington’s story is not just about the past, Elena said to the assembled group.

It’s about how we choose to remember, how we honor the people whose voices were silenced, whose presence was denied, whose love was hidden.

By bringing Clara out of the shadows, by telling her truth, we’re not just correcting a historical record.

We’re affirming that every mother matters, that every person deserves to be seen, that justice can come even 123 years late.

As the sun set over the garden, Elena looked at the photograph one more time, the image that had started this entire journey.

Clara Washington stood in the shadows holding her infant daughter.

Her face now clearly visible to the world.

She was no longer hidden.

She was no longer erased.

She was finally fully undeniably seen.

and her legacy in her descendants and the foundation bearing her name and the countless people inspired by her story would ensure she would never be forgotten

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load