Dr.Elena Vasquez had restored thousands of photographs in twenty years—Civil War cartes-de-visite, glass plate negatives, cabinet cards yellowed by attic summers.

She knew how time smears faces and how water gnaws paper.

But nothing in her career prepared her for the Thornton family portrait from 1901.

On a humid August morning in 2024, she sat in her Cambridge studio, the window cracked to let in the wet air and the sound of sparrows, examining a photograph brought by the Boston Historical Society.

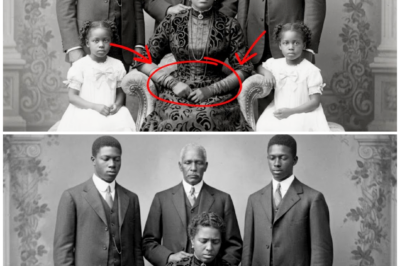

It showed the wealthy Thornton family of Beacon Hill posed in their garden—a carefully composed tableau of brownstone behind clipped hedges: Richard Thornton at center, his wife Catherine beside him, three daughters in white lace, and a boy of about five balanced between adults like a punctuation mark in linen.

It was the kind of image families commissioned to announce stability.

Early twentieth-century portrait photography knew how to stage respectability—the father’s hand on an ornate chair, a mother’s posture straight and kind, children arranged by height and future.

Elena scanned the print at very high resolution and began the work she knew by muscle memory: cleaning mildew spots, adjusting contrast, repairing scratches, bringing back light to eyes dulled by time.

As she brightened the shaded areas near the lawn’s edge, a shape began to resolve beneath a broad oak.

At first, it was easy to dismiss as shadow—a trick of bark and leaf.

But under digital enhancement, the figure sharpened into a woman—Black, dressed in plain domestic clothing—partly hidden by the tree trunk, yet placed so that those who looked closely would find her.

She held an infant wrapped in a white christening gown.

Elena leaned back, heart running.

A Black domestic worker in background was not unprecedented; upper-class family portraits sometimes included servants—visual reinforcement of status.

But this woman’s positioning felt deliberate, as if someone put her in the frame to be seen and then hoped she wouldn’t be.

And the way she held the infant was not casual.

It was what mothers do when they want the world to know.

She examined the child in the woman’s arms—light skin, tiny mouth, tufted hair.

She looked back at the boy between Richard and Catherine—the five-year-old with light brown hair, features echoing the patriarch’s.

A theory formed—the kind historians hear with both head and heart—and she opened the Thornton family file provided by the society.

The documentation listed the subjects: Richard Thornton, textile merchant; his wife Catherine; daughters Margaret, Elizabeth, and Anne; and “nephew James,” orphaned after a cholera outbreak, taken in by the family.

There was no mention of the woman under the oak.

No infant in her arms.

Elena called the museum’s curator, Dr.

Patricia Chen.

“The woman in the shadows is not incidental,” Elena said.

“She’s meant to be visible, but only if you’re looking for her.”

Patricia was intrigued.

The Thornton descendants had donated the collection six months earlier—boxes of photographs, ledgers, letters.

They said they were clearing out an estate and thought the society would want materials from a prominent family.

They showed no particular interest in the content.

“What do you need?” Patricia asked.

“Everything,” Elena said.

“Household accounts, employment records, birth certificates, personal correspondence—anything connected to domestic staff and children born around 1896 and 1901.”

They started with the ledgers—the kind of books that note eggs and coal as well as wages.

In a household account from 1901, Elena found regular payments to domestic servants.

One entry: “Clara Washington—cook and housemaid—$8 per month + room.” It ran from 1899 to 1902.

In the margin, one word appeared abruptly: “Dismissed.”

Elena took photographs of the page, the handwriting, the date.

In personal letters, they found Catherine writing to her sister in Philadelphia in March 1901 about a child—“Richard’s nephew, James”—who had arrived following the “tragic death” of his parents.

“There are unfortunate rumors,” Catherine wrote, “but they are entirely without foundation.

James is our blood and will be raised appropriately.

We have made household adjustments to preserve propriety.”

Rumors.

Adjustments.

Blood.

Elena read the avoidance like a second letter.

Patricia went to Boston City Hall.

The clerk brought bound volumes heavy with births recorded in careful script.

There was a James Thornton born in February 1896, listed as the son of Richard’s deceased brother.

When she requested the death certificates of the supposed parents, the dates did not align.

They had died in 1898, not 1896.

And James’s birth certificate listed Boston as his birthplace, though his parents were living in New York that year.

In the margin, partly obscured by time: “Amended record.”

Someone had changed it.

Elena needed to find Clara Washington.

It was not easy.

“Washington” is stitched through Black Boston’s history like thread, and Clara had left few official traces.

But persistence turned difficult searches into stories.

The 1900 census listed “Clara Washington, age 25, Black, single, domestic servant,” living at the Thornton address.

Ink in the margin noted something unusual: “Infant daughter—not enumerated.”

Hospitals kept better records than households.

Boston Lying-In Hospital—one of the few places in the city where poor women and rich alike delivered—held a February 1896 entry for “Clara Washington, Black, age 21,” who had delivered a male infant.

The father was listed as unknown.

A physician’s note appended to the record read: “Patient employed by R.

Thornton family.

Infant to remain with mother and Thornton household per family arrangement.

Fee paid by R.

Thornton.”

Elena’s theory edged closer to conclusion.

In 1896, a child had been born to a Black domestic worker employed by the Thorntons.

Richard had paid hospital fees.

And a narrative—“orphaned nephew”—had been constructed around a child born in Boston connected to the Thorntons, with altered records to support it.

Clara’s dismissal in 1902 required context.

City directories and church records traced her to a South End boarding house in 1903, working as a laundress.

Then the trail went cold, until Patricia switched archives—moving from civil registries to the careful handwriting of pastors.

In the records of Boston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, she found a baptismal entry: “James Washington, son of Clara Washington,” dated March 1896.

Tucked in the same folder was a letter from Clara to Reverend Williams, dated October 1902.

Clara wrote in steady script:

“Reverend, I write in desperation.

You baptized my son James six years ago.

His father, a man of prominent standing, whom I will not name, provided support and demanded secrecy.

Now that man’s wife has declared my presence unacceptable.

She has insisted I be dismissed and worse, that James will remain with them to be raised as their own.

She says I am unfit to mother him.

She offered me money to leave quietly and never speak his parentage nor attempt to see him again.

He is my son.

I carried him, birthed him, nursed him, and raised him for six years.

But I have no legal standing.

I am a Black woman with no family, no resources, no power.

The Thorntons have everything—wealth, position, law.

If I fight, they will destroy me and possibly harm James.

If I accept, I lose him—but perhaps secure him a life of opportunity I cannot provide.

I do not know what to do.

I pray for guidance—for strength—to do right by my child even as my heart breaks.”

Elena wiped tears as she read.

The letter fixed a date to an impossible choice.

But if James was five in 1901—the boy in the family’s center—and Clara was holding a months-old infant beneath the oak, then two children were in that photograph: James, standing with the Thorntons as their “nephew,” and a younger child in Clara’s arms.

Elena zoomed into the infant’s features and the gown’s lace pattern—details that help historians anchor ages.

The baby was a few months old.

James was five.

She called Patricia.

“There’s another child—born in 1901.

We need to search births around March.”

Boston Lying-In Hospital’s records again answered.

In March 1901, a female infant was delivered to “Clara Washington, Black, domestic servant.” Richard Thornton paid the fees.

The father was listed as unknown.

The notation matched the earlier one.

Patricia checked the Boston Home for Colored Children’s intake records.

In September 1901, a female infant about six months old was surrendered by “Mother: Clara Washington.” A note attached: “Adoption finalized October 1901.

Child placed with family in New York.

Records sealed per family request.

Substantial donation received from anonymous benefactor.”

The photograph’s meaning sharpened.

That summer, Clara had held her daughter in the garden—insistent, if only in the frame, on being seen as a mother.

By autumn, under the weight of wealth and propriety, the infant was gone—adopted away in a hurry financed by a man who had created the child’s existence and then curated its erasure.

“Someone allowed her that moment,” Elena said quietly to Patricia.

“Perhaps Richard, or even Catherine.

The photograph preserves what the family tried to deny: that Clara was mother.”

The question that remained was the one families often bury deepest: What did the child know?

Elena traced James through the decades.

The 1910 census listed him at fourteen in the Thornton household, a “nephew,” attending school.

He graduated from Harvard Law, worked at a Boston firm by 1920.

The 1930 census showed him married, living in Back Bay, children in tow, occupation: attorney.

Under “race,” the initial entry read “mulatto”—amended to “white.” Someone had looked, hesitated, then decided.

Newspaper archives filled in character between dates.

In 1935, James represented a Black family evicted from a white neighborhood—pro bono—against wealthy property owners.

He won.

Over the years, he defended segregation cases, pushed for equal access in schools, fought restrictive covenants.

In 1954, he delivered a speech at the NAACP Boston chapter:

“I stand before you as someone who has benefited from privilege—education, position, respect granted for the color of my skin.

But I know that justice delayed is justice denied.

Separate is inherently unequal.

There are people in our lives—people who love us, who sacrifice, whose contributions go unrecognized.

We owe them a debt.

The least we can do is fight for a world where such sacrifices are no longer necessary, where love and family are not constrained by race.”

Elena wondered if those unacknowledged people had names for him.

Public records led her to James’s grandson, Michael Thornton—a retired professor of African American history—living in Cambridge.

When she called, he was quiet for a long time and then said, “Come over.

There are things you need to see.”

Michael was tall, with eyes that held the weight of someone who had translated personal history into scholarship.

He brought out boxes, envelopes, photographs.

“My grandfather died in 1975,” he said.

“He left a sealed letter asking me to open it after my father died.

I read it five years ago.

It changed everything.”

James’s letter, dated 1974, was addressed to Michael.

It was confession and instruction.

“I am not who the world believes me to be,” James wrote.

“I am the son of Richard Thornton and a Black woman named Clara Washington who worked in our household.

I was raised to treat her as staff until she was dismissed when I was six.

I did not learn the truth until I was thirty.

In 1932, a woman approached me outside my office.

She said she was Clara.

She brought documents—my baptismal record, a letter to her pastor, a photograph of her holding me in the Thornton garden.

At first, I did not believe.

She knew my favorite toys, the song she sang, the birthmark on my shoulder.

I investigated.

Everything was true.

I was angry—at Richard, at Catherine, at everyone complicit.

Clara asked me not to be.

She had made peace.

She had watched me grow from a distance, proud.

She told me about my sister—born in 1901—taken and adopted.

She tried to find her, failed.

She showed me the photograph of her holding the infant—my sister.

I visited Clara until she died in 1935.

I held her hand and called her mother for the first time since I was six.

After her death, I dedicated myself to fighting the injustices she endured.

I became a civil rights attorney because I know how the color line destroys families, forces impossible choices, denies dignity.

Michael, you are a historian.

Clara Washington was your great-grandmother.

Honor her.

If any trace remains, find my sister.”

Michael had been searching for five years—adoption records, orphanage ledgers, names that might match a sealed file.

“The photograph is our proof,” Elena told him.

“If we share it widely—historians, genealogists, families—someone may recognize a story.”

The press conference at the Boston Historical Society drew local and national media.

Elena presented the restored image and the enhanced close-up of Clara under the oak—an insistence sewn into a century.

She explained the documentation—birth records, hospital notes, Clara’s letter, James’s confession—carefully, respectfully, mindful of the complexity of consent and coercion embedded in the story.

Three days later, Michael received an email from Harlem.

Diane Roberts, seventy-nine, wrote that her grandmother had been adopted as an infant in 1901 from a Boston orphanage, told only that her mother was a domestic servant.

“My grandmother kept a small photograph of a Black woman in a garden,” she wrote.

“She thought it might be her mother.”

When Diane sent the photograph, Michael stared.

It was a second print of the 1901 image—cropped to show only Clara holding the infant.

The Thorntons were absent.

Someone—perhaps Richard—had cut the family out and left the mother.

Diane came to Boston.

She and Michael met like cousins who knew they belonged but had to learn how.

At the museum, Elena showed her the full photograph.

Diane cried, hands to mouth.

“She was beautiful,” she whispered.

“She was proud.

She loved me.”

James’s letter made Diane’s throat tighten—siblings separated, lives carried in opposite currents of race, both channeling the strength of a woman neither could keep.

“My grandmother taught in Harlem for forty years,” Diane said.

“She told Black children they were brilliant, prepared them for a world that would say otherwise.

She did for other people’s children what Clara couldn’t do for her own.”

Elena understood the shape of legacy now—how love interrupted can become work, how a photograph can be an archive of resistance.

The story spread.

Historians revisited old images of white families with Black domestic workers at margins that aren’t margins anymore.

Museums curated exhibitions on “Hidden Histories: Black Women in the Shadows of American Photography.” Elena’s restoration anchored the show.

Michael and Diane founded the Clara Washington Foundation—to research forced family separations during Jim Crow and support genealogical work for families splintered by adoption and migration.

They worked with the museum to create a permanent exhibit—photograph, letters, legal cases, context about domestic servitude, anti-miscegenation practices, power imbalances.

The exhibit asked a hard question without pretending there was a simple answer: how to remember Richard Thornton? Clara’s letter offered clarity and complication: “I do not claim to have been forced against my will, but neither can I claim I was free to refuse.

What freedom does a servant have when her employer demands her company? What choice exists when refusal might mean unemployment, homelessness, starvation? I cared for him.

Care bound by such imbalance cannot be called love.”

The exhibit refused to make Richard only villain or progressive.

It presented him as a man whose wealth and position allowed him to exploit a woman’s limited options and whose mercy—paying hospital fees, permitting six years with a son, perhaps arranging a photograph—does not absolve him of what that imbalance created.

Another genealogist contacted Michael.

Linda from Connecticut had discovered her grandmother Sarah was adopted from the Boston Home for Colored Children in October 1901.

DNA testing confirmed what the documents suggested: she was Clara’s granddaughter.

Linda, Diane, and Michael were three branches of a tree severed and somehow still alive.

Together, they visited Clara’s grave in Roxbury—simple and quiet among stones worn by snow.

The headstone was updated: “Clara Washington (1875–1935).

Beloved mother.

Her strength lives on in her descendants.” At the dedication, former students of Diane’s grandmother came, lawyers who had worked with James, neighbors.

Elena spoke about seeing what others had left unseen.

“Clara Washington found a way to be seen,” she said.

“She stood in that garden holding her baby and insisted on being photographed.

That act of quiet resistance is why her story survived.

She knew she might never speak her truth publicly, so she made sure evidence existed—so someday, someone would look closely enough to see her.”

Afterward, Linda hugged Elena.

“Thank you,” she said through tears.

“Thank you for seeing my great-grandmother.

Thank you for refusing to let her stay hidden.”

Six months later, Elena’s work became the centerpiece of Hidden Histories: Black Women in the Shadows of American Photography.

The exhibition showed layers of invisibility and insistence, margins redefined, cropped women restored to frame.

Schoolchildren stood before Clara’s face and learned how photographs tell stories even when people try to make them lie.

Families complicated by race sat together and talked.

Michael’s white-identified children and grandchildren discovered their Black ancestry and wrestled with identity’s new shape.

Diane’s family welcomed them, bringing joy and questions and patience to a reunion a century in the making.

On a shelf in Michael’s study, the 1901 photograph sits in a frame.

Next to it, he keeps James’s letter.

Sometimes he reads the passage about unacknowledged people, sacrifices, love constrained by color, and he understands his grandfather more clearly.

Sometimes he looks at Clara under the oak—jaw set, infant swaddled—and he understands legacy more deeply.

A photograph had been donated by a family as evidence of their place in Boston.

Digitally restored, it revealed a mother’s presence the family had tried to erase.

Decades later, historians, descendants, and strangers gathered around it to reconcile a past split by race.

What experts had tried to explain for decades became something simpler and harder: a woman who insisted on being seen, an image that refused to forget, and a family learning the truth of its foundation in the shadow of an oak.

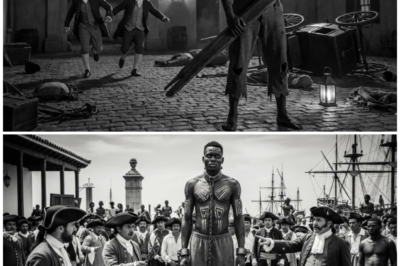

News

It was just a family portrait — but the woman’s glove hid a horrible secret

It arrived with no return address, only a handwritten note: “This belonged to my family. I believe others should see…

Plantation Owner Made His Slave “Breed” with His Prize Bull… Blamed Her When Nothing Happened…

Plantation Owner Made His Slave “Breed” with His Prize Bull… Blamed Her When Nothing Happened The iron bit into Sarah’s…

Samson’s Curse: The 7’2 Slave Giant Who Broke 9 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 25 (Alabama, 1843)

The iron bit into his wrists—iron thick as a man’s thumb, naval-grade shackles built to restrain cannon and men. The…

The Forbidden Feast: How the Plantation Mistress Forced Slaves to Eat Human Flesh (Mississippi,1862)

They still tell it in Wilkinson County, Mississippi. On nights when fog sweeps low across the abandoned rice and cane,…

The Slave Forced to Sleep with the Master’s Wife — And What He Observed Every Night (1847)

The Slave Forced to Sleep with the Master’s Wife — And What He Observed Every Night (1847) In Cuba in…

The 7’6 Giant Who Made His Masters Flee: Cartagena’s Most Disturbing Story (1782)

The 7’6 Giant Who Made His Masters Flee: Cartagena’s Most Disturbing Story (1782) On the night of August 15, 1782,…

End of content

No more pages to load