I.A Forgotten Image, A Hidden Story

In August 2024, deep inside the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, researcher Dr.

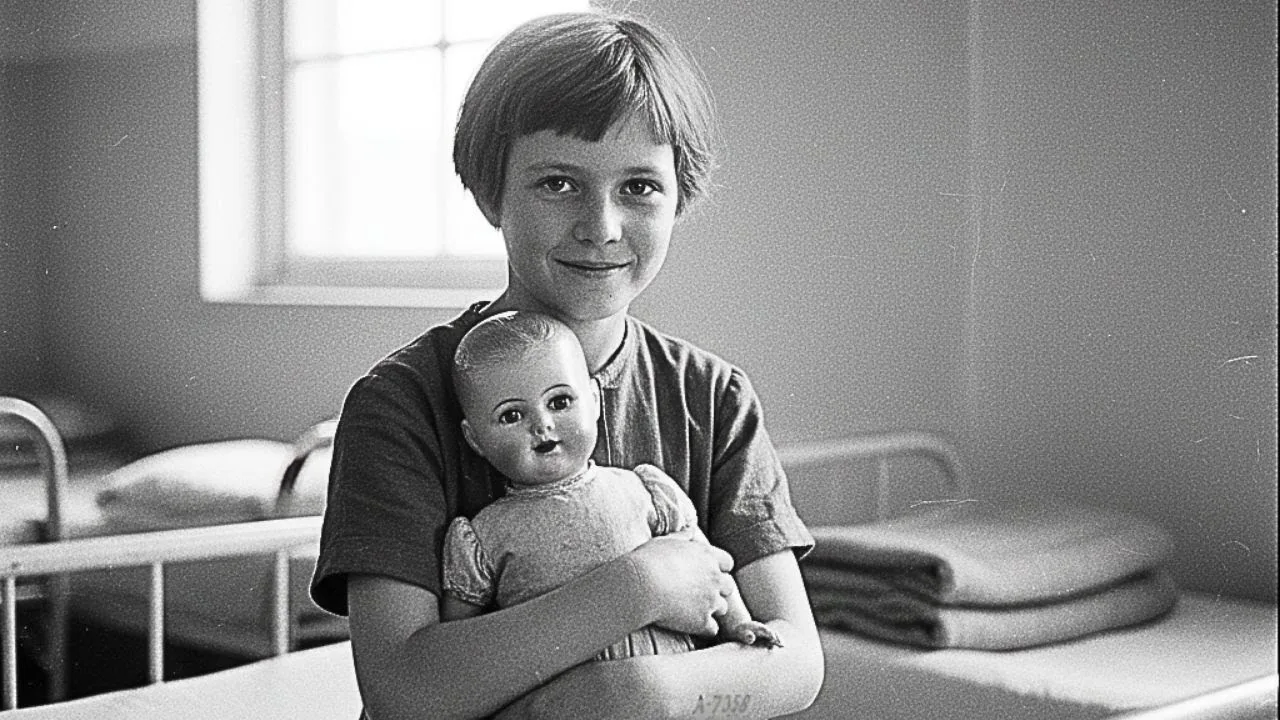

Sarah Lieberman paused over a photograph labeled simply “Unidentified child survivor, May 1945.” The image, taken at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp just weeks after liberation, showed a little girl—about six years old—sitting on a cot in the children’s recovery ward.

She clutched a donated porcelain doll, her tentative smile aimed at the army camera.

It was one of thousands of post-liberation photos, each a heartbreaking testament to survival.

But as Dr.

Lieberman scanned the image at high resolution, zooming in on the child’s left hand, she saw something missed for nearly eight decades: a tattooed number on the girl’s tiny forearm.

It was a detail that would unravel the mystery of her identity and reveal an extraordinary story of endurance, loss, and hope.

II.

The Number That Changed Everything

Dr.

Lieberman specialized in photographic archives and survivor identification.

That summer, she was cataloging 847 photos donated by the family of Captain James Walsh, a US Army medical officer who had helped liberate Bergen-Belsen in April 1945.

Walsh’s collection documented the aftermath: survivors in hospital wards, medical personnel, food and clothing distributions, and children in recovery.

One photo, labeled in Walsh’s handwriting “little girl with doll, children’s ward, May 12th, 1945,” caught Sarah’s eye.

The child wore an oversized dress, her hair unevenly regrowing after being shaved for lice.

She clutched a doll nearly as large as herself.

Her expression was uncertain—trying to smile, but shadowed by trauma.

Sarah scanned the photo at 6,400 dpi, the museum’s standard.

At 400% magnification, she saw it: numbers tattooed on the child’s forearm, just above the wrist.

The tattoo read A-7358.

Sarah’s breath caught.

Auschwitz had tattooed prisoners with identification numbers.

The A-series, used in 1944, marked a specific group—Hungarian Jews deported during the Holocaust’s most intense period.

Most children sent to Auschwitz were murdered immediately.

Those tattooed had survived selection, forced labor, or medical experiments.

For a child this young to bear an Auschwitz tattoo meant she had survived something almost unimaginable.

Sarah searched the museum’s database.

A-7358: female, registered May 28th, 1944.

No name recorded.

No further information.

III.

The Search for A-7358

Sarah began a comprehensive investigation.

She knew the child was female, registered at Auschwitz in May 1944, photographed at Bergen-Belsen in May 1945, likely born 1938–1939, with light brown hair and a thin build.

She researched the A-series: Hungarian Jews, spring–summer 1944, with 440,000 deported and most murdered on arrival.

Only a handful of children survived, often twins selected for Dr.

Josef Mengele’s experiments, older children who lied about their age, or those protected by relatives.

Sarah contacted several organizations:

– Arolsen Archives (Germany): Confirmed A-7358 registered at Auschwitz, but no name or transport list connection.

– Yad Vashem (Israel): Transport records from Munkács, Hungary, to Auschwitz, May 28th, 1944.

Of 3,000 deportees, only 153 were registered and tattooed.

About 12 were children under age 10.

– Bergen-Belsen Memorial Archives: Liberation records showed 500 children under 12 found at Bergen-Belsen in April 1945, many in critical condition, most unidentified.

– Jewish family search organizations: Searched records of children placed in DP camps, orphanages, or with foster families.

After three weeks, Sarah found a breakthrough: a handwritten list from Bergen-Belsen’s children’s ward, May 1945.

Entry #47: “Female child, approx.

age 6, Auschwitz tattoo 7358, speaks Hungarian, nonresponsive to questions, placed in care of UNRRA.”

IV.

From Number to Name

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) had taken custody of thousands of displaced children.

Sarah tracked down a transfer document dated June 18th, 1945: “Child A-7358, name unknown, transferred to Jewish children’s home, Paris, France, accompanied by survivor Eva Klene, nurse volunteer.” The note read: “Child exhibits severe trauma, does not speak, requires ongoing medical care and psychological support.”

Sarah contacted the Paris home’s archivist.

On September 15th, 2024, she received scanned intake records:

– June 22nd, 1945: Hannah Goldberg, approx.

age 6, from Munkács, Hungary.

Auschwitz prisoner A-7358, liberated from Bergen-Belsen.

No known surviving family.

Severely malnourished, tuberculosis, does not speak, tattoo on left forearm, placed in medical ward.

Sarah had a name: Hannah Goldberg.

V.

Hannah’s Recovery and New Life

The records traced Hannah’s slow recovery:

– July 1945: Remained nonverbal, responded to her name, showed fear of adults, accepted comfort from female caregivers.

– September 1945: Began speaking Hungarian, asked repeatedly for “Anya” (mother), suffered nightmares.

– December 1945: Physical health improving, tuberculosis treatment ongoing, psychological trauma severe, attached to Eva Klene.

– March 1946: Began playing with other children, severe anxiety persisted, refused to let go of her doll—the one given to her at Bergen-Belsen.

The doll in the photograph became Hannah’s security object, her connection to hope after unimaginable loss.

Records showed she kept it for years.

VI.

From Orphan to Family

In 1948, Eva Klene, a Polish Jewish survivor and Hannah’s caregiver, legally adopted her.

In 1949, they immigrated to New York City.

Hannah attended public schools, lived with Eva, completed high school.

In 1970, Hannah Goldberg married David Rosenberg.

Over the next decade, she gave birth to three children: Rebecca, Sarah, and Jacob Rosenberg.

In 1985, a New York Jewish community publication featured Hannah’s testimony at a Holocaust remembrance event: “I was 6 years old when I was liberated from Bergen-Belsen.

I don’t remember my parents’ faces.

I remember the camps, hunger, fear.

But I also remember the day I was given a doll—the first toy I’d received in over a year.

That doll represented hope, kindness, the possibility that the world could be good again.

I kept that doll my entire life.

I showed it to my children.

I told them, ‘This is what hope looks like.’”

VII.

The Meeting: Past and Present Collide

Sarah discovered Hannah was still alive, living in a Florida retirement community at age 84.

She contacted Holocaust survivor services, who arranged a meeting.

On October 15th, 2024, Sarah met Hannah Goldberg Rosenberg.

Hannah’s daughter Rebecca was present for support.

Hannah was small, white-haired, sharp-eyed, walking with a cane.

On her left forearm, the faded tattoo: A-7358.

Sarah showed her the photograph.

Hannah stared at the screen, tears running down her face.

“That’s me.

That’s the doll.

I haven’t seen a picture of myself from that time in 79 years.

The camps didn’t take photographs.

My family had no cameras.

I had nothing from that time except my memories, the tattoo, and the doll.”

“Do you still have the doll?” Sarah asked.

Hannah nodded, retrieved a carefully wrapped box.

Inside was the same porcelain doll, paint faded, dress yellowed, but intact.

“I named her Hope,” Hannah said.

“When I had nightmares, I held Hope.

When I was scared, I held Hope.

When I had my own children, I told them Hope’s story.

She represented the kindness that still existed in the world, even after so much evil.”

VIII.

The Full Story Emerges

With Hannah’s help, Sarah documented the complete story:

– Born February 1939, Munkács, Hungary (now Ukraine).

– Family: Father Jacob Goldberg (tailor), mother Miriam Goldberg (seamstress), brother David Goldberg (age 8 in 1944), extended family of about 35.

– May 1944: Forced into Munkács ghetto with 14,000 Jews.

Deported to Auschwitz on May 23rd, 1944.

– Arrival at Auschwitz, May 28th, 1944: During selection, five-year-old Hannah was pulled from her mother’s arms—perhaps by error, perhaps a momentary decision.

She was tattooed and sent to the children’s barracks.

Her family was murdered in the gas chambers within hours.

– Survival: Hannah endured in the children’s barracks through luck, protection from older prisoners, and her small size.

She was used for medical experiments—non-lethal but traumatic.

– Transfer to Bergen-Belsen, January 1945: As Soviet forces approached, prisoners were evacuated west.

Hannah survived the death marches and horrific conditions at Bergen-Belsen until liberation.

– Liberation and Recovery: British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen on April 15th, 1945.

Hannah, severely ill, recovered slowly in the hospital.

The photograph was taken May 12th, 1945—two weeks before her sixth birthday.

IX.

Legacy and Remembrance

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum added Hannah’s story to their permanent collection.

The 1945 photograph, now identified, became part of an exhibition: “Faces Found: Identifying the Unknown Survivors.” Hannah provided video testimony for the museum’s archive.

In her testimony, Hannah said, “For most of my life, I was just a number—A-7358.

The Nazis tried to erase my name, my identity, my humanity.

They tattooed me with a number to mark me as property, less than human.

But I survived.

I reclaimed my name.

I built a life.

I had children and grandchildren.

The number is still on my arm, but it doesn’t define me.”

“That photograph shows a moment of transition—between being a number and becoming Hannah again.

Between being a victim and becoming a survivor.

Between having nothing and receiving something—a doll, a small gift, but it represented everything: hope, kindness, humanity.”

“I want people to see that photograph and understand every victim of the Holocaust was a person with a name, a family, a story.

We were not just numbers.

We were human beings.

And those of us who survived have an obligation to tell our stories so the world never forgets.”

X.

The Doll Named Hope

Hannah donated the doll, Hope, to the Holocaust Memorial Museum.

It sits in a display case next to the photograph, with a placard: “This doll was given to Hannah Goldberg, Auschwitz prisoner A-7358, shortly after liberation from Bergen-Belsen in May 1945.

She kept it for 79 years as a symbol of hope and humanity’s capacity for kindness, even in the darkest times.”

Today, Hannah’s family includes three children, eight grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

Her extended family, all descended from a six-year-old survivor, numbers over 30.

At a family gathering in November 2024, Hannah’s great-granddaughter, age six—the same age Hannah was in the photograph—asked to hold the photo.

“That’s you, great-grandma?” she asked.

“Yes,” Hannah replied.

“You look sad.”

“I was very sad then.

But see the doll? That doll gave me hope.

And hope is what helped me survive to become your great-grandmother.”

The little girl studied the photograph.

“Can I see your number?” Hannah showed her forearm, the faded tattoo.

The child gently touched the numbers.

“Does it hurt?”

“Not anymore,” Hannah said.

“It used to hurt every day.

But now it’s just a reminder that I survived.”

XI.

The Meaning Behind the Image

What began as a “cute” photo of a little girl and her doll became a symbol of survival, resilience, and the power of kindness.

A number tattooed on a child’s arm, hidden in plain sight, led to the recovery of a lost identity and the restoration of a family’s history.

Hannah’s story reminds us that every photograph contains worlds beneath its surface—stories of suffering, hope, and humanity.

It is a testament to the obligation we all share: to remember, to honor, and to ensure that the world never forgets.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load