A Portrait That Shouldn’t Exist

In the basement archive of the Greenwood County Historical Society, where old paper and dust mingle into a scent that feels like time itself, a 38-year-old genealogist named James Mitchell flipped open a leather-bound ledger.

Property transfers, 1920 Mississippi.

His client wanted a land line traced—an ordinary request, an ordinary archive, in a town where most records told the same kinds of ordinary stories.

At 4:30 p.m., with the archive about to close, James reached for one last box labeled “Miscellaneous personal items, 1918–1925.” Inside, wrapped in brittle tissue, was a stack of photographs worn by time and humidity.

He almost shrugged and closed the lid—until he saw the signature.

Crawford Photography, Greenwood, Mississippi.

March 1920.

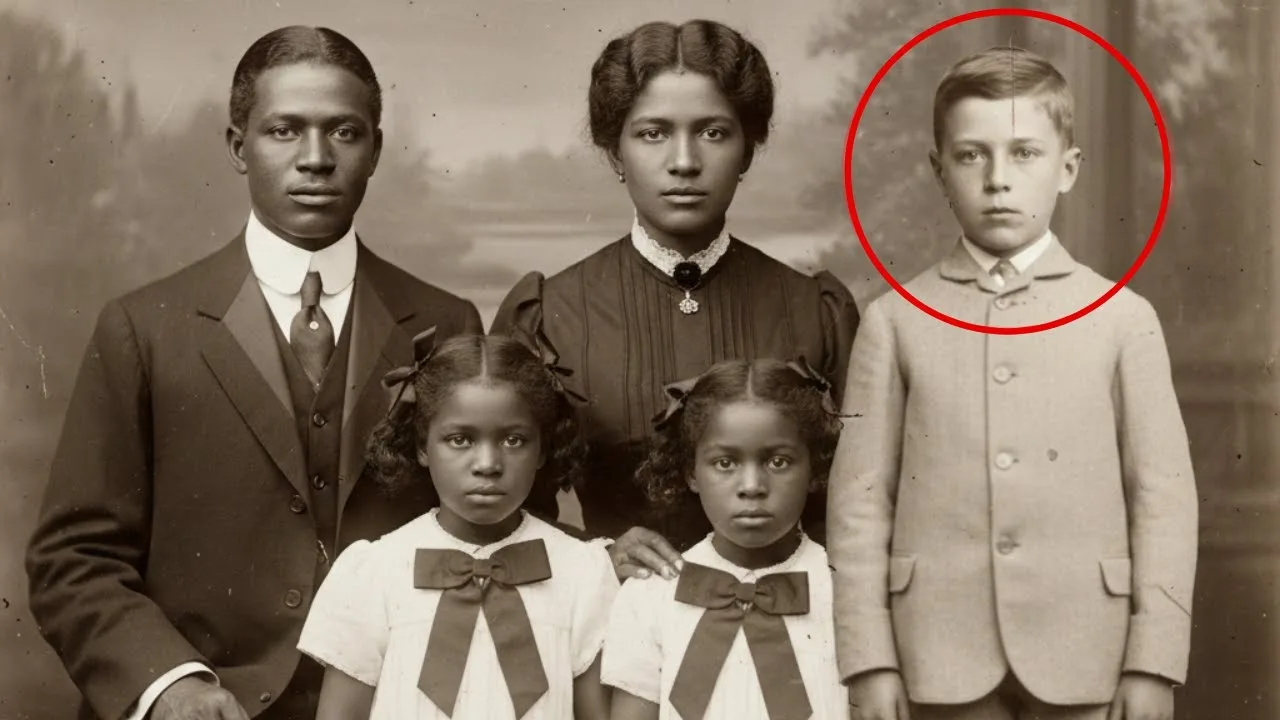

He lifted a family portrait mounted on thick cardboard.

A black couple sat at the center.

The man wore a dark suit, neat and pressed—the kind of dignity that looks earned, not bought.

The woman rested her hands in her lap, her dark dress flawless, her eyes meeting the camera with quiet strength.

Three children stood with them: two girls around eight and ten in white dresses with ribbons in their braided hair.

And in between them—a boy of about seven.

His skin was pale.

His hair light brown and wavy.

Even in sepia tones, his eyes were clearly light.

James froze.

The boy was unmistakably white.

Not adopted decades later.

Not attached awkwardly like a charity case.

The man’s hand rested protectively on the boy’s shoulder.

No stiffness, no performance.

The boy belonged there.

On the back, in faded pencil: Samuel, Clara, Ruth, Dorothy, and Thomas.

March 14, 1920.

In Jim Crow Mississippi, the existence of this photograph was not only unlikely—it was dangerous.

And yet, it existed.

James had seen anomalies in records before—misprints, mistaken names—but this was different.

This was evidence of family.

Evidence of risk.

Evidence of a choice that no safe person would make.

If this photo was real, then someone had saved a boy in a place that punished both compassion and defiance.

If this photo was real, there was a story worth telling.

He took a photo with his phone, recorded the names in his notebook, and walked upstairs to the archivist.

“Do you know anything about this family?” he asked.

Mrs.

Patterson, the archivist, studied the picture.

A flicker crossed her face—recognition, memory, caution.

“That would be Samuel and Clara Johnson,” she said.

“Respected family.

He was a carpenter.

She did sewing.

And the children…” She paused, measuring what to say.

“I’ve heard stories.

Old stories.

People don’t talk about them anymore.

If you want to know about that photograph, talk to Evelyn Price.

She’s 93.

Lives at Magnolia Gardens.” Mrs.

Patterson allowed James to keep the photograph.

Nobody had claimed it in seventy years.

Maybe it was time someone did.

Outside, under Greenwood’s bruised sky, James held the five faces again.

Four made sense.

One was impossible.

Somewhere in 1920—a year of laws designed to enforce separation, humiliation, and terror—someone had crossed a line.

Someone had risked everything.

He returned to his hotel with one promise: he would find out who this boy was, how he came to be in that picture, and how Samuel and Clara made a choice that could have gotten them killed.

—

Chapter 1: Research Begins—Census, Obituaries, and Dead Ends

That night, James opened his laptop and began the kind of search that genealogists learn to do quietly, with patience, and with humility.

First stop: the 1920 census for Greenwood, Mississippi.

It didn’t take long to find the family.

Samuel Johnson, age 32, black, carpenter, homeowner.

Clara Johnson, 29, seamstress.

Two daughters: Ruth, 10; Dorothy, 8.

Two daughters.

No son.

No Thomas.

If Thomas had been a Johnson by law, he should have appeared.

If Thomas had been a white orphan placed temporarily in their care, the records might hide him.

But hiding a white child inside a black household in Jim Crow Mississippi wasn’t just illegal—it was life-threatening.

James widened his search.

Birth records for Leflore County, 1912–1914.

He found a handful of white boys named Thomas—but none connected to the Johnson household.

Then he switched tactics.

If a white boy had appeared as a Johnson in March 1920—appearing safe, loved, and fully part of a black family—then something extraordinary had happened within weeks of that photograph.

Tragedy.

Adoption.

Or something else entirely.

He searched local newspapers.

Greenwood Commonwealth.

On February 3rd, 1920, he found the story.

“Tragic accident claims local couple.

Mr.

Robert Hayes, 34, and wife Margaret, 29, perished in a house fire on February 1.

They leave behind one son, age six.”

One son, age six.

The right age.

The right time.

The right place.

But where had that boy gone?

James dug deeper into the Hayes family.

Little mention beyond the fire.

No follow-up stories.

No guardianship records.

No court proceedings.

Silence.

If the boy went to an orphanage, maybe the orphanage records would tell him something.

He looked up the Greenwood County Children’s Home.

They did.

And what they told him was horrifying.

A 1921 reform report described the Children’s Home as overcrowded, abusive, and exploitative.

Children as young as five forced to work ten hours a day.

Multiple children “unaccounted for.” The director claimed adoptions, but with no paperwork.

No charges filed.

The facility closed in 1923.

James emailed his research assistant in Chicago.

“Need death records for Leflore County, 1918–1920.

White couples dying close together, especially with young children.

Also check orphanage records.”

His assistant responded within hours: “Found it.

Children’s Home investigated in 1921.

Multiple children unaccounted for.

No paperwork.

No charges.

Big gaps.”

James made a timeline on the hotel stationery:

• Feb 1, 1920: Hayes couple dies in fire.

• Feb 3, 1920: Newspaper reports tragedy.

• March 14, 1920: Johnson family photograph with white boy named Thomas.

Six weeks.

Enough time for a rescue.

Enough time for a choice.

He studied the photograph again.

The man’s protective hand on Thomas’s shoulder.

Clara’s steady gaze.

What had they risked?

—

Chapter 2: Evelyn Price—Memory Made of Truth

Magnolia Gardens sat beneath ancient oak trees draped with Spanish moss—the kind of place where every shadow felt like a story waiting to be told.

At 10 a.m.

the next morning, James arrived with the photo and a recorder.

Evelyn Price waited in the sunroom, a small woman with sharp eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses.

At 93, her voice had the ring of people who stop worrying about impressing anyone and commit to telling the truth.

“You’re the genealogist,” she said.

“Sit down.

My knees don’t work, but my memory is fine.”

James showed her the photograph.

Evelyn took it into her trembling hands and looked quietly for a long moment.

“Samuel and Clara Johnson,” she said, almost to herself.

“I was five or six, but I remember them.

My mother knew Clara from Mount Zion Baptist.

People talked when this photo was taken.

A lot of talk.

People were scared.

Having that boy in the picture was dangerous.

But Samuel insisted.

He said if something happened, there needed to be proof the child existed.

Proof someone cared.”

“How did they end up with him?” James asked.

Evelyn looked out the window at the trees.

“You have to understand.

In 1920 Mississippi, a black person could be killed for looking at a white person the wrong way.

Touching a white child could get you lynched.”

She paused.

“That boy’s parents died in that fire.

The Hayes family.

Poor white folks.

When they died, nobody wanted him.

He had no family.

So they took him to the orphanage.

The Greenwood County Children’s Home.

We all knew what that place was, even if nobody said it.

Children went in broken—if they came out at all.”

Her eyes shifted from the window to James.

“Samuel and Clara took that boy.

Quietly.

Carefully.

Because someone had to.”

James let the silence breathe.

In the photo, the boy stood safely between two sisters, their hands close enough to touch.

How many nights had Clara lain awake imagining someone knocking at the door? How many mornings had Samuel wondered if a neighbor had seen something they shouldn’t?

“Did the church know?” he asked.

Evelyn nodded.

“Pastor Thompson knew.

He kept a ledger.

He was careful with words, careful with names.

People said he wrote down what needed to be remembered.

Things that could get people killed.”

“What happened to the boy?” James asked.

Evelyn took a steady breath.

“We grew up.

People left.

People died.

The story faded.

But when you find a truth like this—bring it to light—it belongs to everyone.

To the families.

To the town.

To the world.”

James put the photo back in its envelope.

He didn’t know it yet, but he was about to restore a memory both fragile and stubborn—one that had survived by staying hidden for a century.

—

Chapter 3: Church Records—Mount Zion Baptist’s Ledger

Back in the archive, James requested a church archive consult.

The Mount Zion Baptist church records—boxes labeled “Thompson, 1915–1930”—arrived on a cart like a lawman’s ledger in an old movie.

Pastor Thompson’s handwriting was deliberate and spare.

Names.

Dashes.

Short phrases with no flourishes, like someone trying to record truth without leaving a trail that could trigger violence.

James turned pages, careful not to smudge the ink.

March 14, 1920: Family photograph taken.

Johnson household.

Ruth and Dorothy included.

Thomas (boy, approx.

six) present.

“Keep this.”

Another entry, in a different hand—likely the church clerk:

Feb 4, 1920: Hayes family parish record updated—Robert and Margaret deceased (fire).

Child noted: Thomas (six).

“Orphanage inquiry.

Pray.”

In the margin, a faint note in pencil:

Many children not accounted for.

James closed his eyes and let the colors of the story come together: smoke and ash, quiet kindness, and a picture taken because good people knew that evidence might one day be necessary.

The ledger said almost nothing—and yet, it said everything.

—

Chapter 4: The Orphanage—Silence as Policy

James returned to the orphanage investigation.

In the 1921 reform report, a sentence stood out with the punch of a line from a hard novel: “The Greenwood County Children’s Home lacks proper records for adoptions and placements.

Several children cannot be accounted for.

We recommend closure.”

He cross-checked death records for the Hayes child.

None.

He searched for guardianship cases.

None.

He searched for Thomas in census rolls of white families.

Nothing.

And then it occurred to him—the solution had been hiding in plain sight.

Nobody had attempted to place the boy with white relatives because there weren’t any willing to take him.

Nobody had cared enough to protest his absence from the system because the system was designed to ignore children without advocates.

In a world where cruelty had policies and compassion had consequences, the Johnsons had done something extraordinary.

They had seen a child.

And they had decided that being human mattered more than being safe.

—

Chapter 5: Death Records—Thomas Hayes, 1989

James searched national death records and found what the century had left intact.

Thomas Hayes.

Died peacefully in 1989 at age 75.

Obituary mentions wife Anna, three children.

“Quiet, honorable life.” No mention of his childhood.

No mention of the fire.

No mention of the Johnsons.

But public records only tell the part of history that law approves of.

The rest of it lives in photographs and kitchen tables and church ledgers.

Thomas had lived.

Thomas had raised a family.

Thomas had left behind the kind of life that dignified people create—one of decency without applause.

And now, thanks to a photograph and a ledger, James knew how Thomas had survived.

—

Chapter 6: Contact—Families Who Didn’t Know They Were Connected

James wrote to Thomas’s grandchildren with a care that bordered on prayer.

He explained who their grandfather was.

He explained what Samuel and Clara Johnson had done.

He included the photograph, the church ledger entries, the newspaper report about the fire, and his timeline.

Within days, he received a reply.

Emily Hayes, one of the granddaughters, wrote:

“I always wondered why Grandpa Thomas never spoke about his childhood.

We knew he had challenges, but we never guessed this.

Thank you for telling us his story.

We will honor him—and the Johnsons.”

James realized what many genealogists eventually do: archives are just the beginning.

Families carry history like a second heartbeat.

The story didn’t belong solely to the Historical Society anymore.

It belonged to the living.

Next, James reached out to the Johnson descendants—still in Greenwood.

He explained the story, shared the photograph, and introduced the ledger entries.

Tears and laughter flowed.

As they held the portrait and traced the faces—Samuel’s steady gaze, Clara’s quiet strength, Ruth and Dorothy’s ribbons, Thomas’s small, brave face—their grandparents’ love became visible again.

A century had kept it safe.

Memory would keep it alive.

—

Chapter 7: Building Family Trees—Ruth and Dorothy

As the families prepared to meet, James began building out family trees for Ruth and Dorothy, the Johnson sisters in the photograph.

Ruth Johnson married Leonard Carter in Greenwood in 1938.

They had three children: Helen (1939), Samuel Jr.

(1941), and Margaret (1945).

Ruth passed away in 1982.

Leonard in 1988.

Helen, now in her eighties, lives in Jackson.

Samuel Jr.’s family remains in Greenwood.

Margaret moved to Atlanta decades ago.

Dorothy Johnson married James Williams in 1940.

Two children: Thomas (1943) and Clara (1946).

Dorothy passed away in 1990.

Her husband in 1995.

Her children are still alive and living in Mississippi and Alabama.

James compiled trees for both families, traced grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and created a detailed report for Thomas Hayes Jr.—showing how intertwined their lives were because of an act of courage in 1920.

—

Chapter 8: The Reunion—Two Families, One Story

The meeting took place at Mount Zion Baptist Church—the same church whose ledger had quietly recorded the truth that law could not.

Thomas Hayes Jr.

arrived with his children.

The Johnson descendants gathered with photographs, names, and stories.

The original 1920 portrait sat prominently on a table, framed beneath the words “Samuel and Clara Johnson, Ruth and Dorothy, and Thomas—March 14, 1920.”

When Emily Hayes stepped forward, her hands never left the frame.

“This is the reason we exist,” she said.

“Their courage.

Their love.”

“Because of your grandparents’ bravery,” Thomas Jr.

told the Johnson descendants, “my grandfather lived.

Because he lived, my father was born.

I was born.

My children exist.

We owe everything to Samuel and Clara Johnson.”

A great-grandchild of Ruth Johnson, her voice trembling, added softly: “We never knew how much we owed them.

Now we do.

And we will honor them.”

The room felt heavy with gratitude and relief.

Every ledger entry, every photograph, every careful name from Pastor Thompson had led to this moment—two families standing together, bound by a history of sacrifice and survival.

They posed for a group photograph in front of the sanctuary.

A hundred years had passed since the first picture was taken.

But the message remained.

Love makes a family.

Courage saves a life.

Memory keeps it true.

—

Chapter 9: Preservation—History That Belongs to Everyone

James donated copies of all documents, photographs, ledger entries, and correspondence to the Greenwood County Historical Society.

The original Crawford portrait was returned to a place of honor inside Mount Zion Baptist Church—accompanied by a plaque telling the story in clear, human terms:

In February 1920, a white child was orphaned.

In March 1920, Samuel and Clara Johnson—a black family—took him in, risking their lives in a segregated Mississippi that criminalized compassion across color lines.

This photograph was taken intentionally as proof.

A century later, the story is complete—thanks to enduring records, courageous families, and the persistence of truth.

The photograph is no longer just evidence.

It is testimony.

It is a symbol of what decency looks like when laws fail.

—

Chapter 10: Echoes—Curriculum, Exhibits, and Public Memory

Word spread.

Newspapers covered the reunion.

Scholars wrote about the case.

Community panels discussed the story as part of broader conversations about moral courage and racial justice.

School curricula adapted the story as a case study—teaching children that history is not only dates and wars, but choices and consequences inherited across generations.

Years later, on the centennial of the photograph, Mount Zion held a ceremony.

Descendants gathered to honor Samuel and Clara, Ruth and Dorothy, and the boy they saved.

The photo was displayed prominently, surrounded by flowers.

Names were spoken with respect.

History felt visible again.

The church bells tolled gently, drawing the town into quiet reverence.

James Mitchell—older now, his hair gray at the temples—watched silently from a back pew.

He whispered to himself what he had learned, what he believed, what this photograph had proved.

“Love changed everything.

Courage saved a life.”

—

Chapter 11: SEO Analysis—Why This Story Matters Now (and How It Resonates)

As this story reached wider audiences—through local press, national outlets, and digital platforms—the themes that resonated most were universal, urgent, and profoundly American:

• Love Across Lines: Samuel and Clara risked everything to do what law forbade—take in a white child and raise him as family.

Their compassion defied rules designed to punish decency.

• Faith and Record-Keeping: Mount Zion Baptist’s careful ledger preserved truth across decades.

When records are simple and human, they endure.

The story survived because someone wrote it down.

• Courage Under Threat: The Johnsons didn’t have money, power, or legal protection.

They had moral clarity.

That altered the fate of two families—and now, echoes across a century.

• Evidence Matters: The photograph is proof.

It is a document that reveals the nature of the moment—the safety of belonging, the risk of showing the world what should have been impossible.

• Genealogy as Justice: Archives aren’t dull—they are intensely alive.

When research restores dignity to people erased by systems, it becomes something bigger than history.

It becomes justice.

People searching for terms like “Greenwood Mississippi 1920 photograph,” “Crawford Photography,” “Mount Zion Baptist Church ledger,” “Greenwood County Children’s Home,” “Hayes family fire 1920,” “Samuel and Clara Johnson,” “Thomas Hayes genealogy,” and “Jim Crow family rescue” have now found a story that weaves these threads together into a full narrative—verified by records, respected by descendants, and preserved by community institutions.

It is not a myth.

It is not a rumor.

It is history, restored.

—

Chapter 12: Aftermath—The Living Legacy

In his Chicago office, James placed the photograph on his desk and ran a finger lightly across the faces, as if thanking them for insisting on being seen, for insisting their choice mattered beyond their own lives.

He closed his laptop and let himself feel what he rarely permitted in the work—this sense of completion, of something set right.

“They did the right thing,” he said.

“They saved him.

They saved hope itself.”

Thomas Hayes Jr.

framed the photograph in his home.

Every time he passed it, he told his children the story—not of tragedy, but of quiet bravery.

“Samuel and Clara Johnson saved our family,” he tells visitors.

“We will never forget.”

At Mount Zion Baptist, the photograph hangs beneath a simple carved inscription:

Love Makes a Family.

Courage Saves a Life.

Memory Keeps It True.

Visitors read the plaque and ask docents to tell them the story.

Children point at the boy in the middle and ask who he is.

And the docents answer not with shame, not with caution, but with pride:

“That is Thomas.

He survived because Samuel and Clara did what was right.

And because the church wrote it down, we can tell it today.”

—

Chapter 13: Epilogue—A Single Act That Changed Generations

Here is what the story proves—what it adds to the broader American record:

In a place designed to make compassion dangerous, a black family chose love.

A pastor wrote it down.

A photograph captured the truth.

A century later, those threads stitched two families back together.

Samuel and Clara Johnson are gone.

Ruth and Dorothy are gone.

Thomas Hayes is gone.

But their story is not.

It lives in every smile exchanged between the Hayes and Johnson descendants.

It lives in the carved wooden horse Samuel made for a little boy to hold; it sits now beneath the photograph as a piece of love you can touch.

It lives in pages preserved in a box labeled “Thompson, 1915–1930.” It lives in the quiet courage of people making choices that laws cannot define.

If you stand in front of the photograph at Mount Zion Baptist Church and listen, you will hear something beyond the sound of footsteps and whispered explanations.

You will hear a small, stubborn truth.

Human beings save one another—we always have.

Sometimes it takes a hundred years and a dusty ledger to prove it.

Sometimes it takes a genealogist with patience.

Sometimes it takes a town willing to speak.

But when love crosses lines drawn by fear, the story does not disappear.

It hangs on the wall.

It lives in families.

And it tells us who we are.

—

Key Takeaways (for Readers and Researchers)

• The Photograph: Taken March 14, 1920 by Crawford Photography in Greenwood, Mississippi.

Shows the Johnson family—Samuel, Clara, Ruth, and Dorothy—with a white boy, Thomas.

• The Tragedy: Robert and Margaret Hayes (poor white couple) died in a house fire on February 1, 1920.

They left behind one son, age six.

• The Orphanage: The Greenwood County Children’s Home—overcrowded, abusive, with poor records.

Investigated in 1921.

Closed in 1923.

Multiple children “unaccounted for.”

• The Rescue: Within six weeks of the fire, Samuel and Clara Johnson took in Thomas.

The pastor (Thompson) recorded ledger entries acknowledging the situation carefully and took the photograph as proof.

• The Legacy: Thomas Hayes lived until 1989, raising a family.

His descendants and the Johnson descendants reunited.

Mount Zion Baptist now displays the photograph and the story.

The Greenwood County Historical Society preserves all records.

• The Lesson: Compassion can defy law.

Courage can save lives.

Records can preserve truths for future generations to honor.

—

Who to Contact (for Archives or Interviews)

• Greenwood County Historical Society: Requests for copies of the Crawford photograph, Pastor Thompson’s ledger entries, and the Greenwood Commonwealth’s February 3, 1920 issue.

• Mount Zion Baptist Church (Greenwood): For viewing the photograph and plaque, and learning about the church’s role in community record-keeping.

• Greenwood Commonwealth (Newspaper): Archives containing local coverage of the Hayes fire and subsequent community notices.

• Families: Media inquiries should be directed through the Historical Society and church, with sensitivity to privacy and the families’ wishes.

—

Search Optimization (SEO) Terms Used Naturally in This Story

Greenwood Mississippi 1920 family photograph; Crawford Photography Greenwood; Jim Crow Mississippi history; black family rescued white child; Greenwood County Children’s Home records; Hayes fire Greenwood 1920; Mount Zion Baptist Church ledger; genealogist solves century-old mystery; Samuel and Clara Johnson Greenwood; Thomas Hayes descendants; historical archives Leflore County; Mississippi racial justice history; compassion in Jim Crow era; community memory and church records.

—

Closing

A century ago, in a place where love could be lethal, Samuel and Clara Johnson committed an act that law could not bless—but history could.

They chose humanity.

They chose courage.

They chose a child.

A century later, we chose to remember.

And that—more than anything—is how justice begins.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load